Editor’s Note by Noah: Attack on Titan is currently being serialized in English, by Kodansha USA. You can purchase it from Amazon here

_____

I’m starting to feel alone in my disappointment with Pacific Rim. I mean, I know the critics agree with me – even the ones who liked the movie admit it lacks psychological complexity, is full of one-dimensional stock characters, and often drags. But somehow gentle criticism doesn’t seem like enough when Pacific Rim is – really – the best example yet of why screenwriters shouldn’t force every blockbuster into the Save the Cat! mold.

I mean, my friends liked – no, loved – this movie. They loved the Kaiju designs, cast, and art direction. They’ll defend the movie against people who point out that there didn’t need to be four – count ’em, four – “plot twists” or reversals, mostly all predictable. (The first twist is the exception – that one was surprising and quite moving.) Or that there didn’t need to be a 15-minute narrated prologue that boiled down to “monsters appeared so we built giant robots to fight them, P.S. I am your obligatory knucklehead fly-boy protagonist”. Or that between the big set pieces, the movie was mostly one long planning or training sequence.

They’ll even defend the fact that nearly every character is a walking cliche. Or, if they are less passionate in their opinions, they’ll say what everyone says: that it’s just a mindless summer blockbuster, so really, what were you expecting? Don’t you know that all of these big-budget action movies are being made for an overseas audience, anyway?

So maybe my problem with Pacific Rim isn’t that the movie was awful, but that I went into it with the wrong mindset – because truthfully I was expecting something much, much better.

Described to me as “Guillermo del Toro makes a live-action Evangelion“, I was expecting a very different movie: not Evangelion, obviously, but something with at least a little bit of the psychological depth and roller-coaster pacing of that anime. Instead I found a movie built for defense, not suspense: it’s armor-coated against anyone’s possible complaint that it didn’t hit the right note at the right time. (Headstrong protagonist check, strong female love interest check, stern commanding officer check, eccentric scientist double-check, minorities in non-speaking roles, check).

Some plot points are similar to Evangelion’s – the monsters that suddenly appear from a portal over Antarctica/the Arctic, the shadowy global organization that requires pilots to mind-meld in giant robots to fight them, the pilot-pilot romance – but those are pretty superficial similarities, really. Pacific Rim is a very different, and far less cynical, beast – which is fair enough, considering that Guillermo del Toro’s most popular movies have generally been made for children.

Anyway, I was wrong to expect classic cult-hit anime Evangelion. What I should have expected was current cult-hit anime Attack on Titan.

So let’s not talk about Pacific Rim. It’s a monster movie made for an international audience; it hits all the right notes; it looks great. There are even one or two genuinely moving scenes. It’s kid-friendly and has positive, uplifting messages about humanity. (In short, it’s boring.) Let’s not even talk about Evangelion, since Pacific Rim has very little in common with that anime.

Instead, let’s talk about Hajime Isayama’s Attack on Titan.

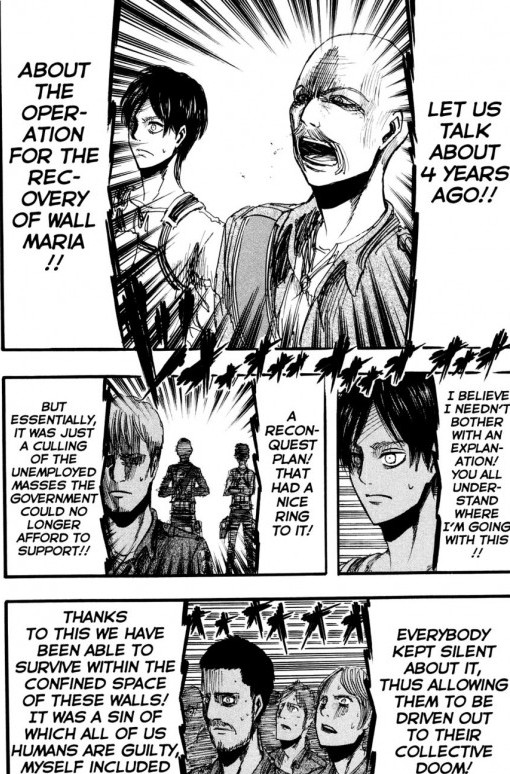

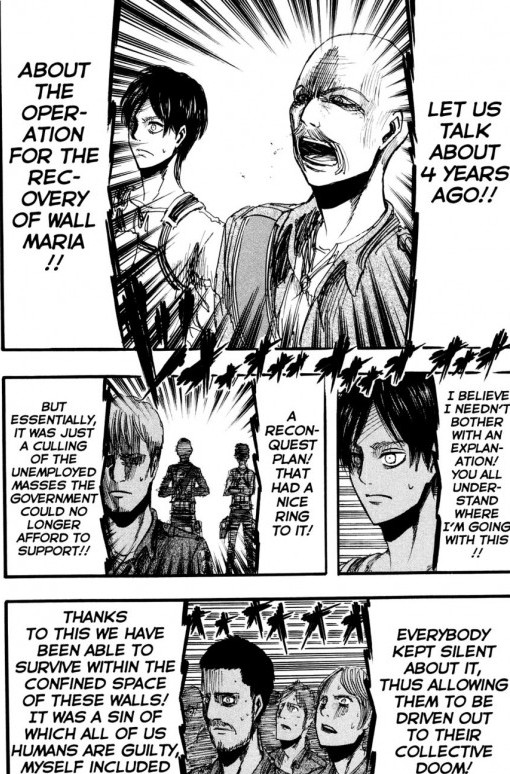

In the world of Attack on Titan, humanity has retreated behind three colossal walls. (In Pacific Rim, there is a plan to build a colossal wall, but it fails right away.) The wealthy and politically powerful live in the innermost ring, where they barely worry about being attacked by human-eating monsters. The hard done-by live in cities projecting from the wall of the outermost ring, where their main purpose is to attract Titans. It’s not economical to defend the whole wall, you see, so concentrating people as bait in small areas reduces the area that needs to be defended.

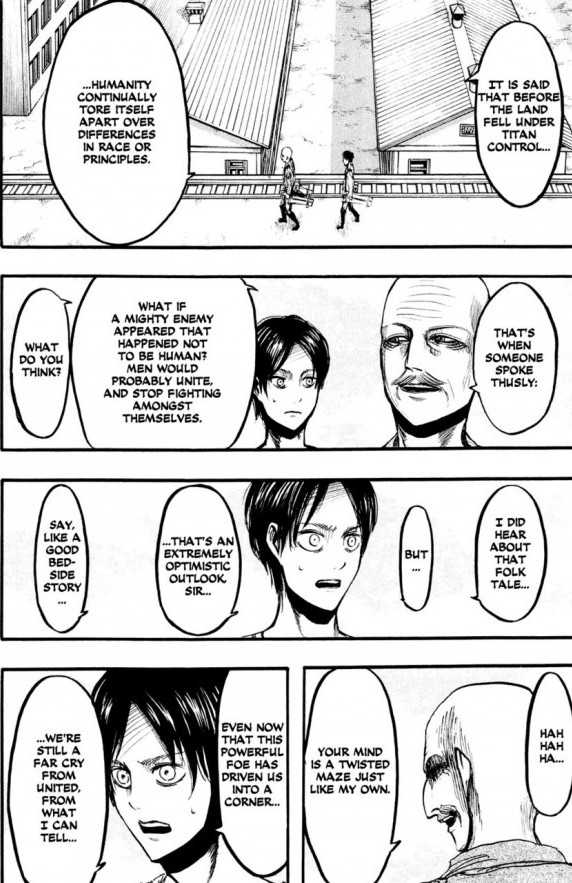

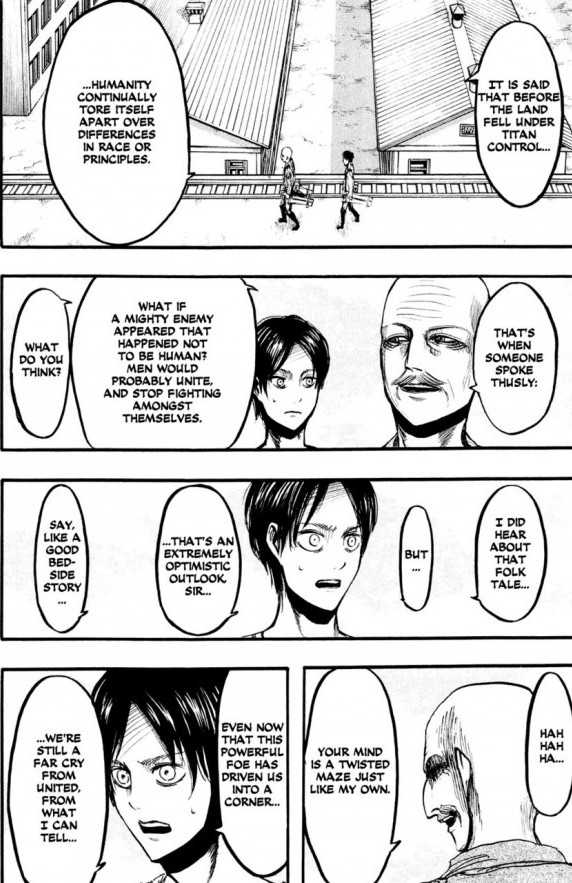

From the set-up alone, you can feel the cynicism, right? Attack on Titan is a fairly cynical – or you could say realistic about the failings of large-scale social structures – series. Pacific Rim supports the well-worn, slightly unfashionable trope of humanity banding together when faced with a common threat; Attack on Titan, on the other hand, interrogates it:

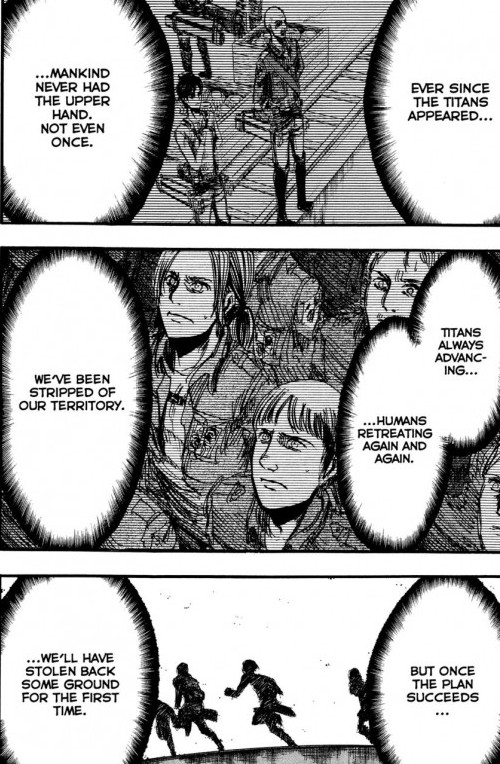

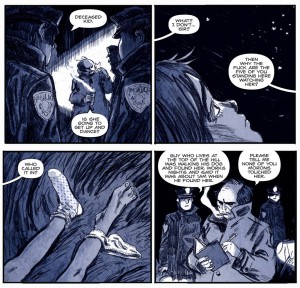

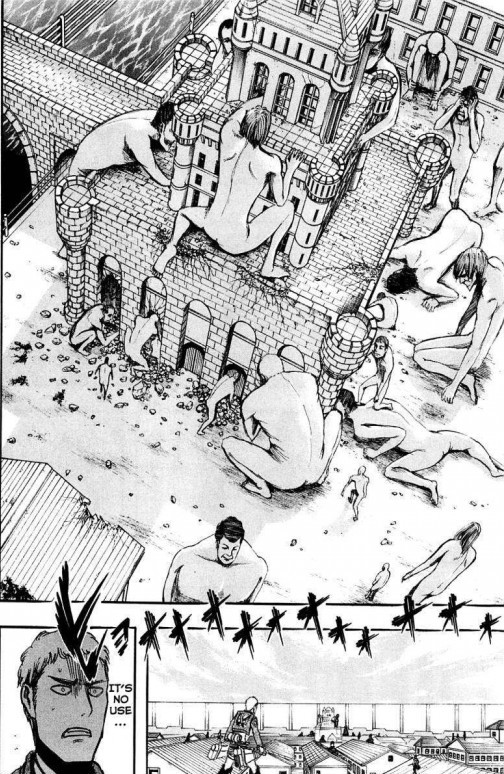

The source of horror is different, too: more threatening, more personal, and harder to fight. In Pacific Rim, the monsters are absolutely victorious for a short time… but only before the movie starts, and only offscreen. For 90% of Pacific Rim’s running time, barring one or two on-screen causalities, humanity is containing the threat.

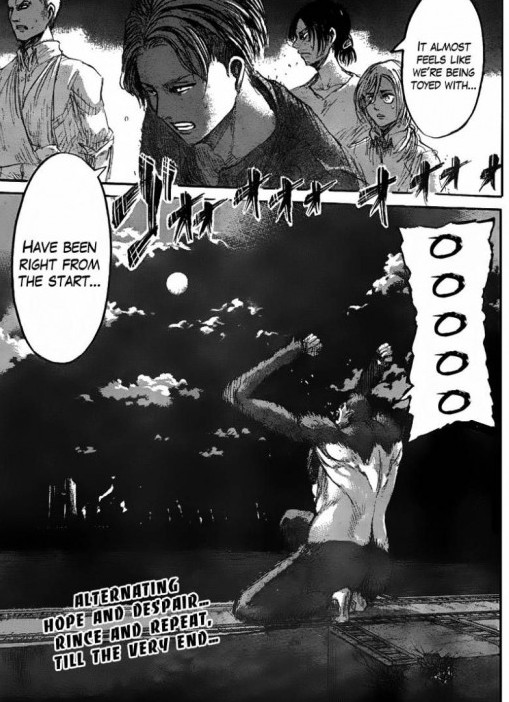

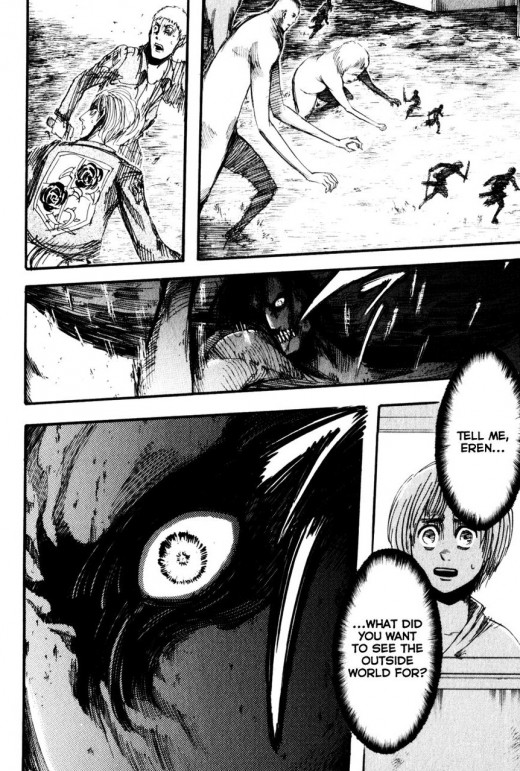

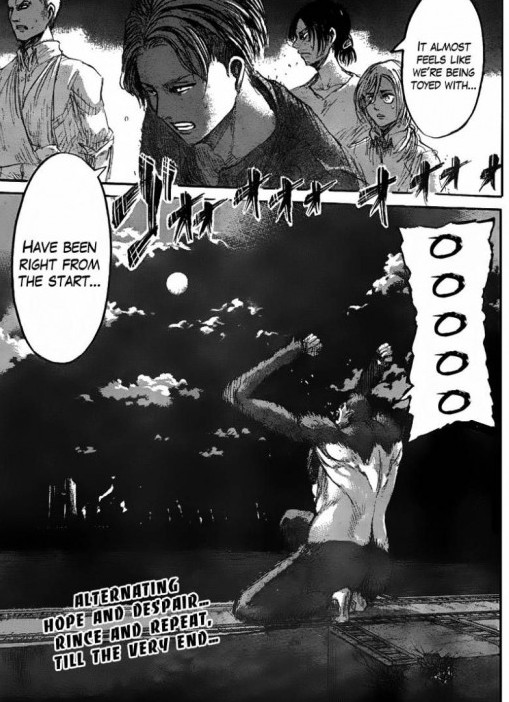

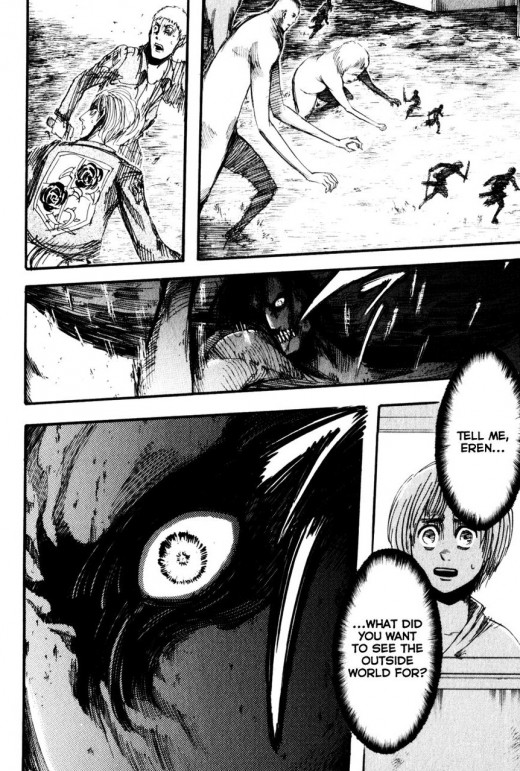

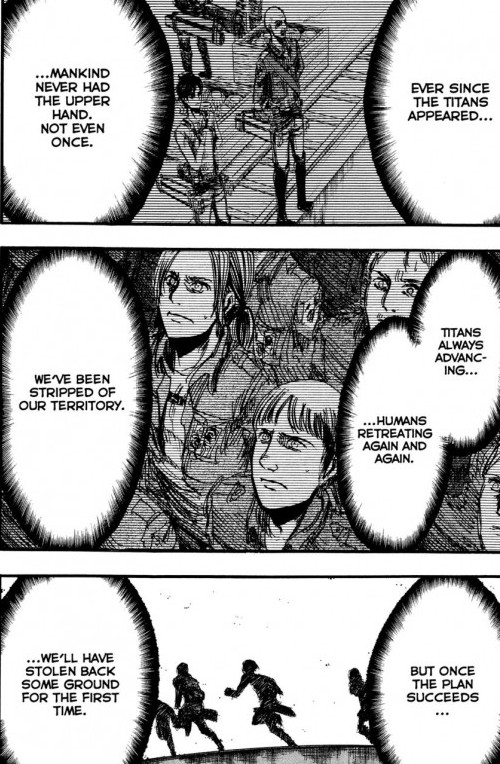

In Attack on Titan, however, just when it seems that people finally have the upper hand, the monsters evolve intelligence – or armor – or kung-fu – or even more monstrous size, and whatever advantage humanity might have had is taken away. And then it’s back to being chased, trapped, overcome, and eaten, by horrible monsters that are impossibly bigger and stronger than you.

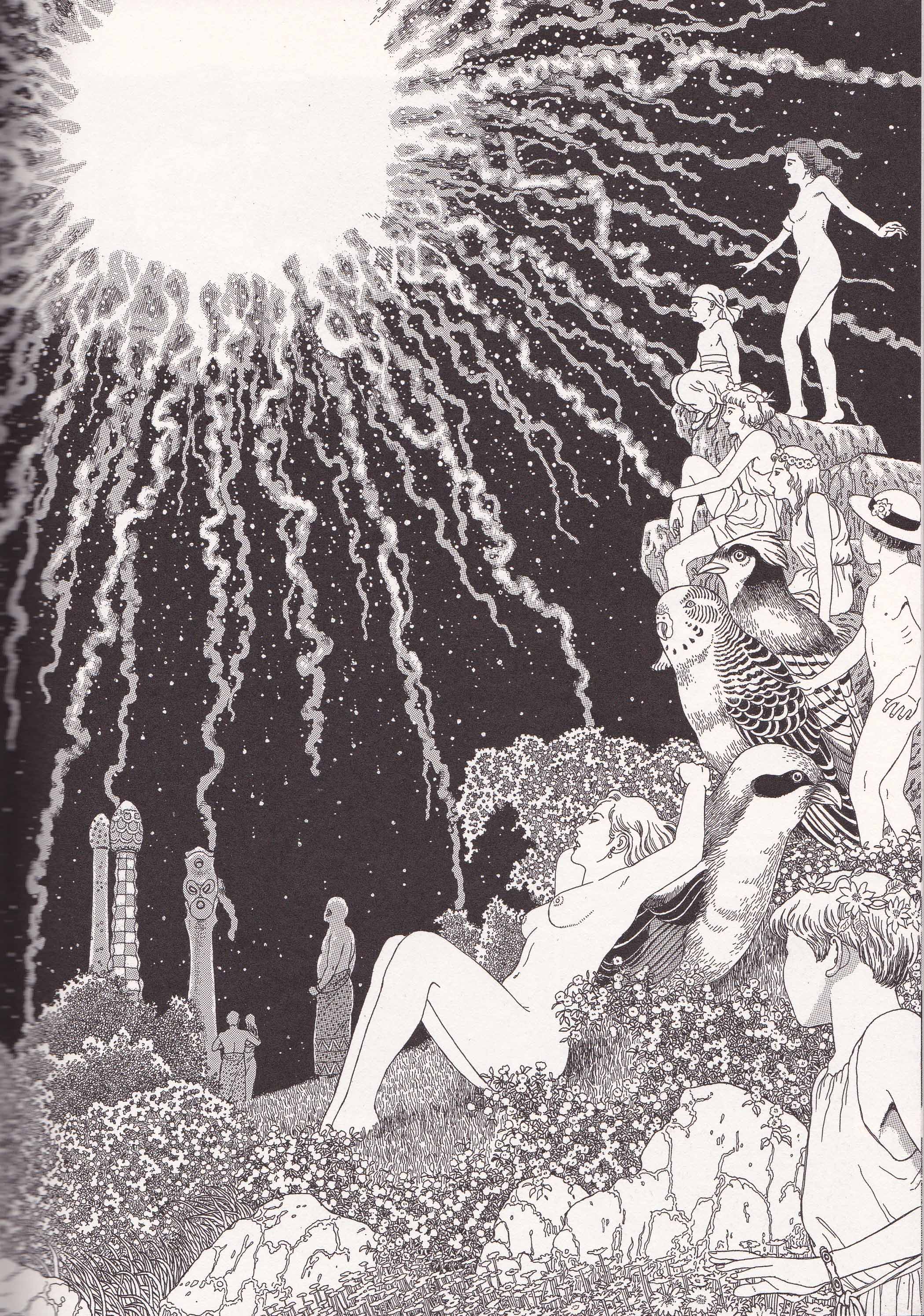

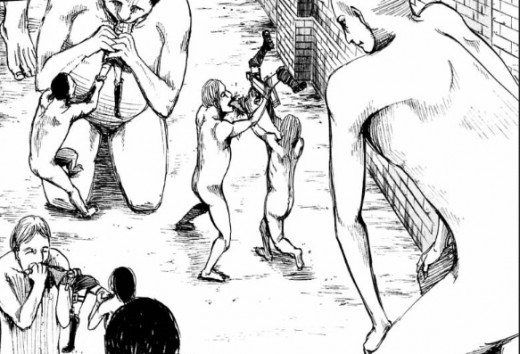

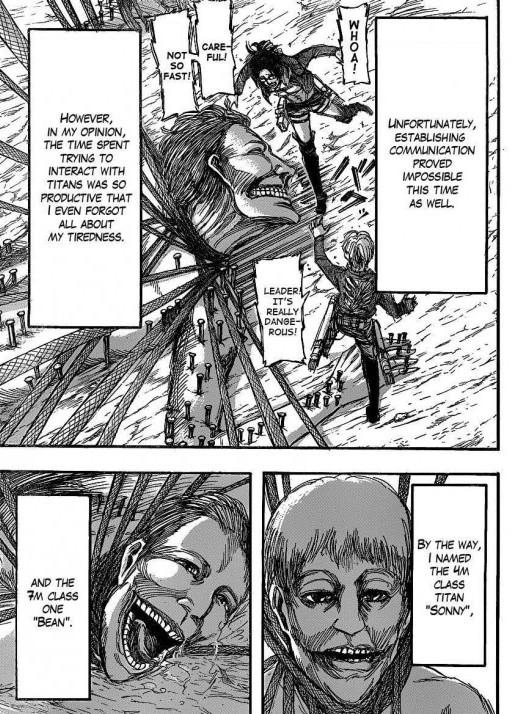

The Titans… why do they exist? Why do they eat people? Why are they sometimes only 9 feet tall, and sometimes over 50 feet tall? Why are some unclothed and some armored? Why are some mindless and some intelligent? Why do some behavior predictably and others unpredictably?

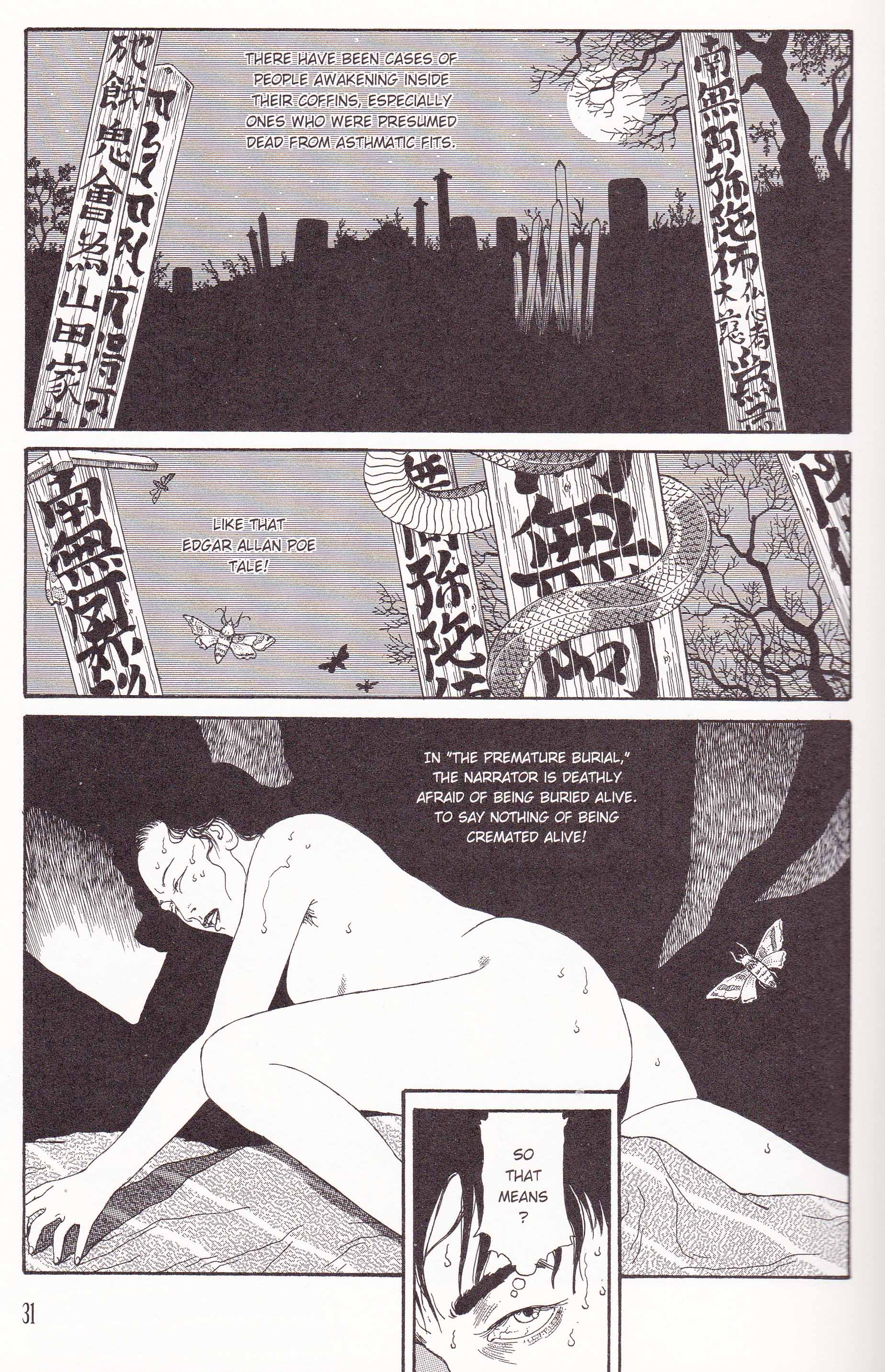

It’s all a mystery. Each time humanity makes some progress toward understanding the Titans, the Titans become that much more horrible and unstoppable in response. The logic here is the logic of nightmares – that you can’t escape, that you’ll always be devoured in the end. It is the horror-movie logic of absolute powerlessness.

The mysteriousness of the Titans is a big part of what makes them horrible. That’s because once you know what something is – once you know how it can be defeated – you have already taken the first step on the path from powerless victim to crafty survivor. Knowledge is the difference between an existentialist horror movie like The Grudge – where the only way to win against the haunted house is to not enter it in the first place – and a survivalist horror movie like the American remake of The Grudge. There are moments of hope in Attack on Titan, but the overall tone is bleak: when the monsters outnumber the humans and are practically impossible to kill, what can be done?

The Kaiju attacks in Pacific Rim are quite different – they only appear to be random, but are in fact highly regular, to the point that they can be predicted mathematically. As explained by Eccentric Scientist#2, the kaiju appear first in an uninhabited place and then head for major population centers, where they primarily damage infrastructure. At first they appear singly, with long gaps in between, allowing humanity plenty of time to regroup. As the movie progresses, they show up more frequently. The fights between the monsters and the robots are destructive – we see Hong Kong basically leveled – but due to this attack pattern they are also clean, with minimal casualties.

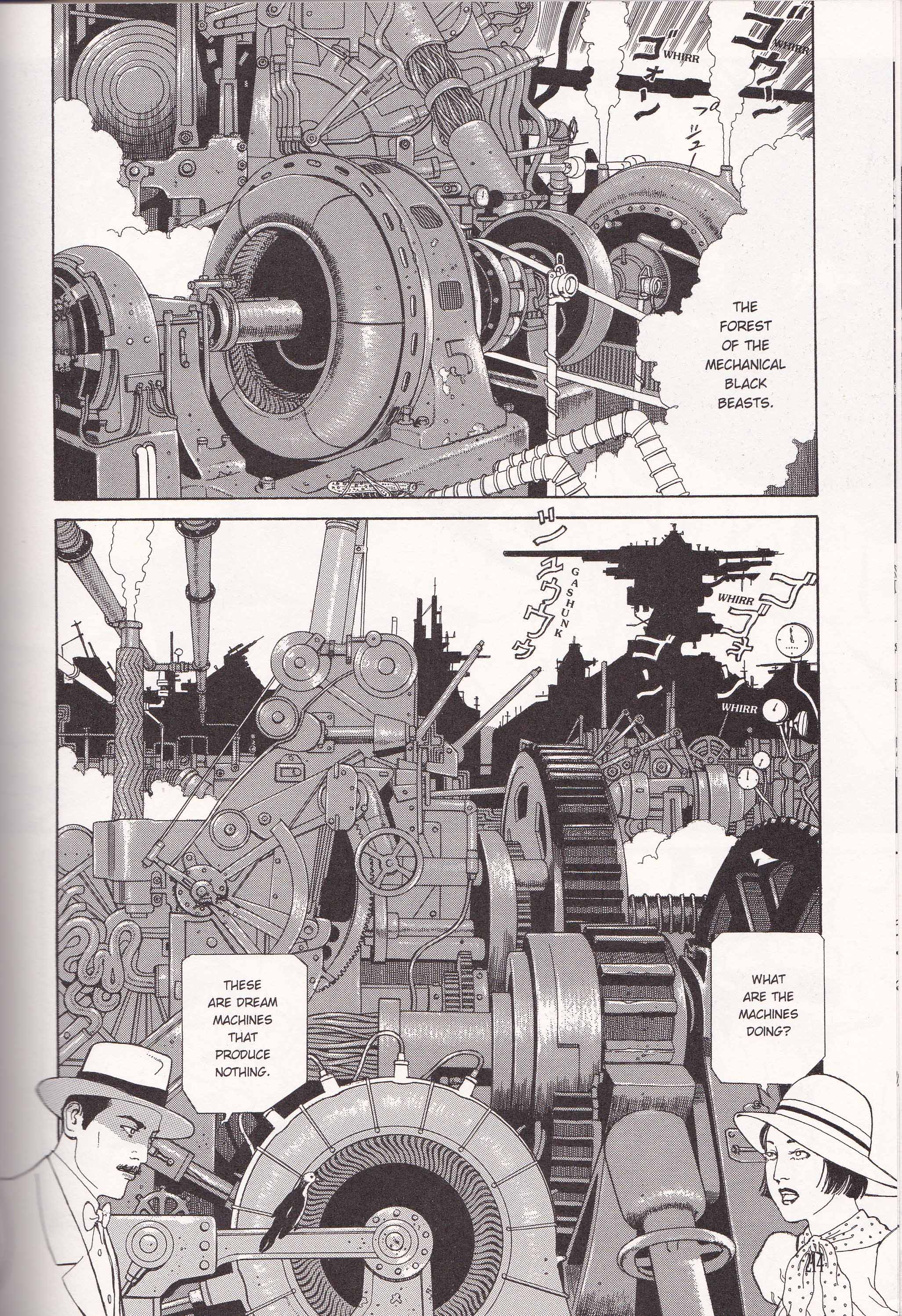

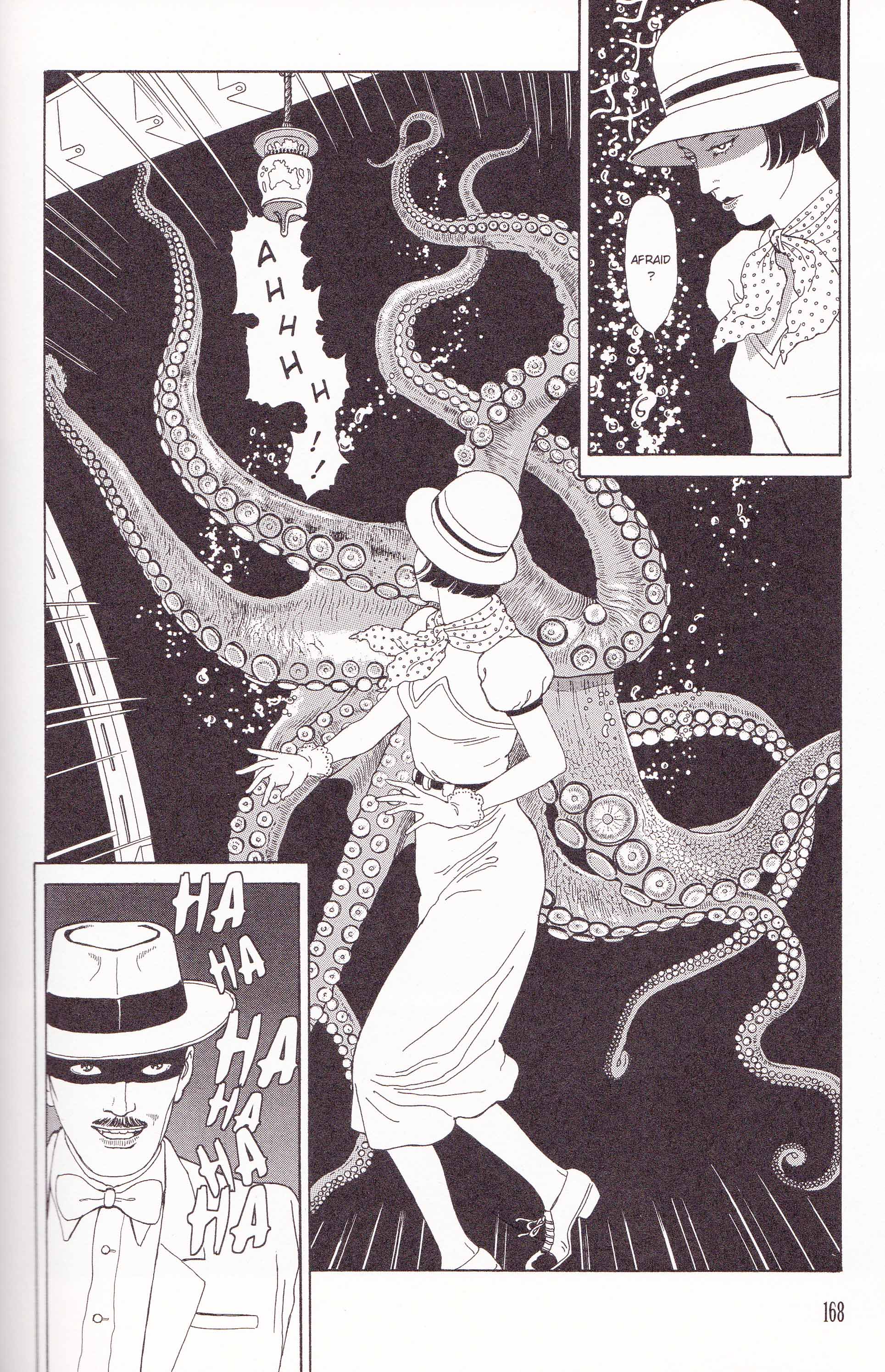

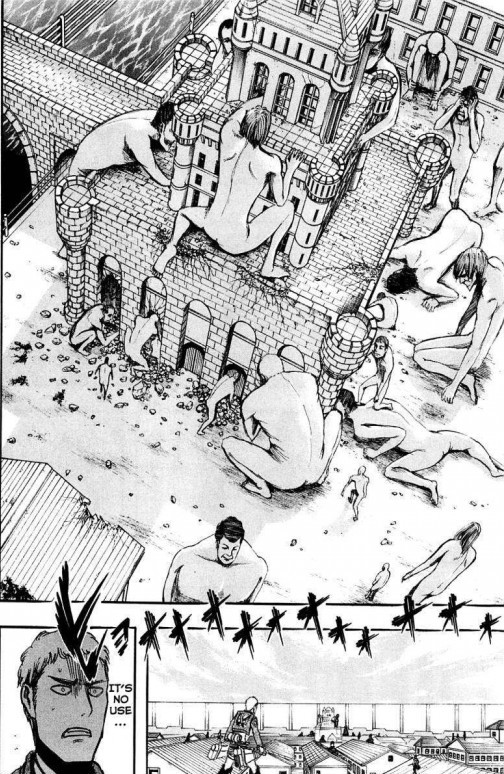

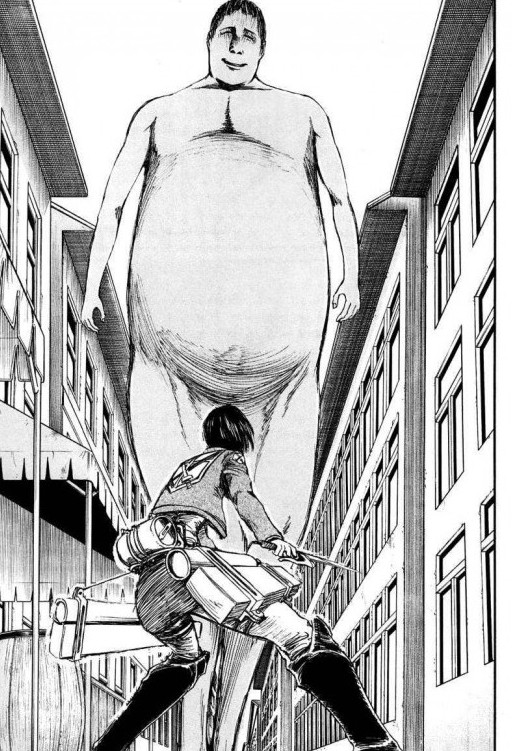

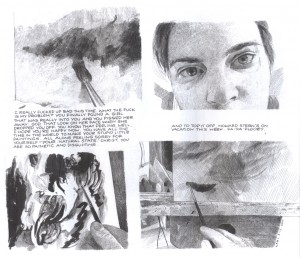

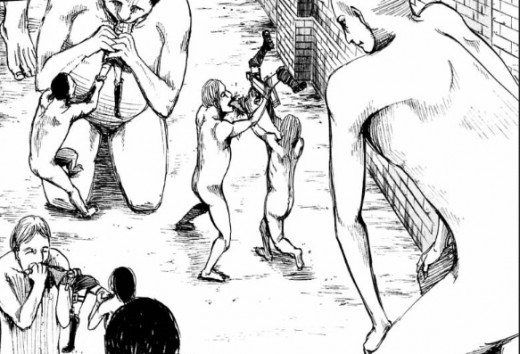

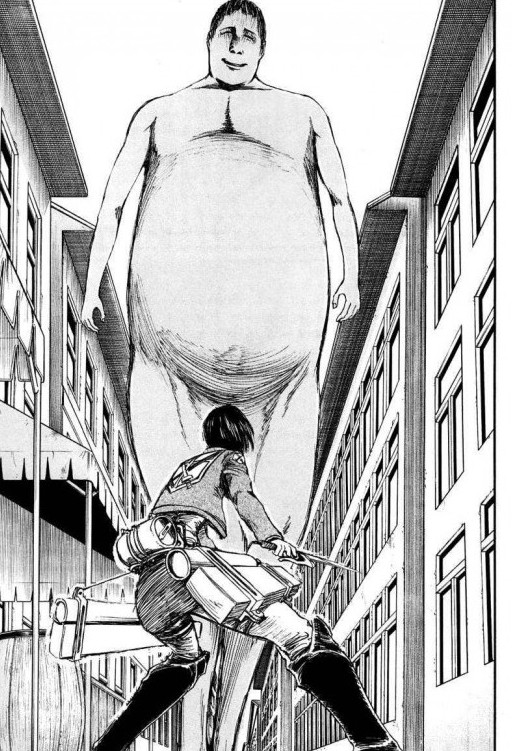

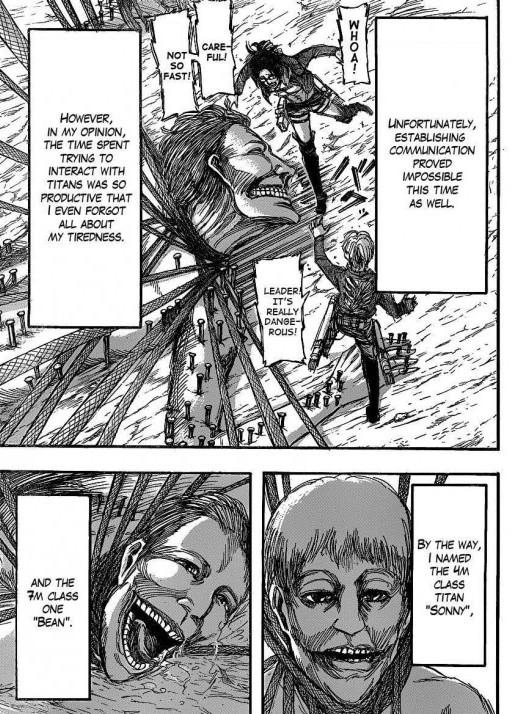

In Attack on Titan, the action is smaller-scale and messier. The monsters look like us – like nude people, but bigger and uglier, with sharper teeth. Regular humanity doesn’t have giant robots, or even tanks or guns: only canons, swords, “gas packs” and climbing hooks. The fights are up close and personal… and so are the losses.

You see, the Titans have no interest in property damage. They exist only to eat people. They don’t need to eat people – they don’t have stomachs, are hollow inside.

So why do they eat people? Because eating people is horrible.

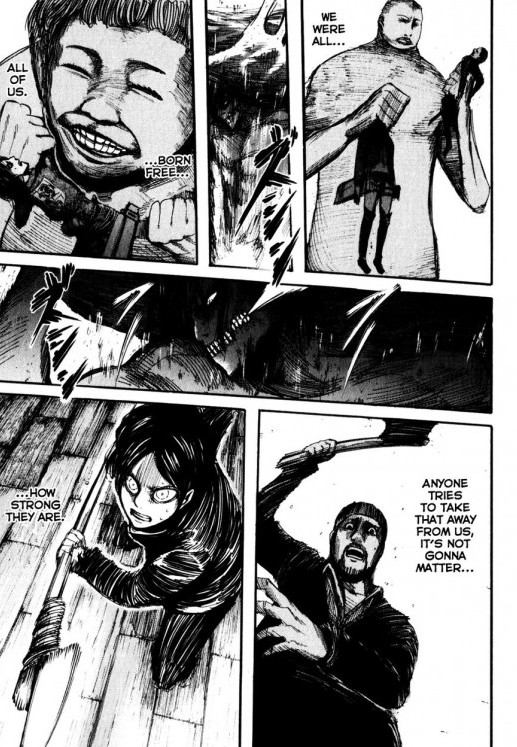

But don’t get me wrong: Attack on Titan isn’t purely a horror series. At first it seems that way: in a prologue from the point of view of the three main characters as children, the Titans can’t be resisted, and so everyone who doesn’t escape from them is eaten. Once the main characters grow up and join the army, however, the tone changes. We find out that the military Scouts – who seemed incompetent from the outside – actually do know a thing or two about fighting Titans. In fact, they know quite a lot! Occasionally they are even able, with the skills and knowledge they have painstakingly acquired, to temporarily win against the Titans.

The protagonists constantly learn and adapt, but it’s never enough. The manga is a push and pull between gaining power to venture out into the unknown; and finding out that the world is more even more unpredictably cruel than you had imagined. That kind of push-pull, between power and powerlessness, is similar to Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure, and indeed you can see a kind of homage in one sequence involving an intelligent, sadistic giant monkey.

Jojo fans who’ve read Part 3: Stardust Crusaders will know what I’m talking about here.

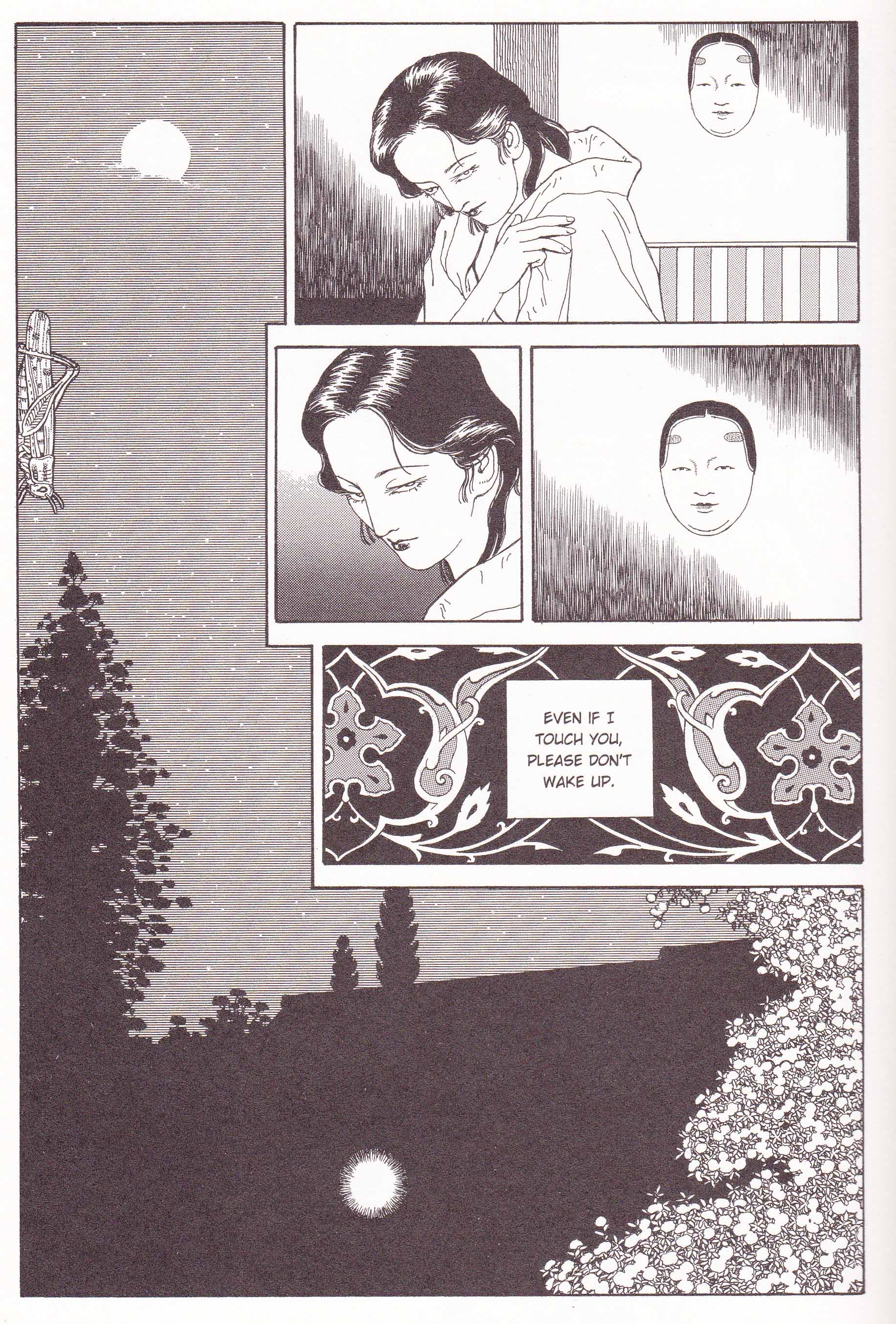

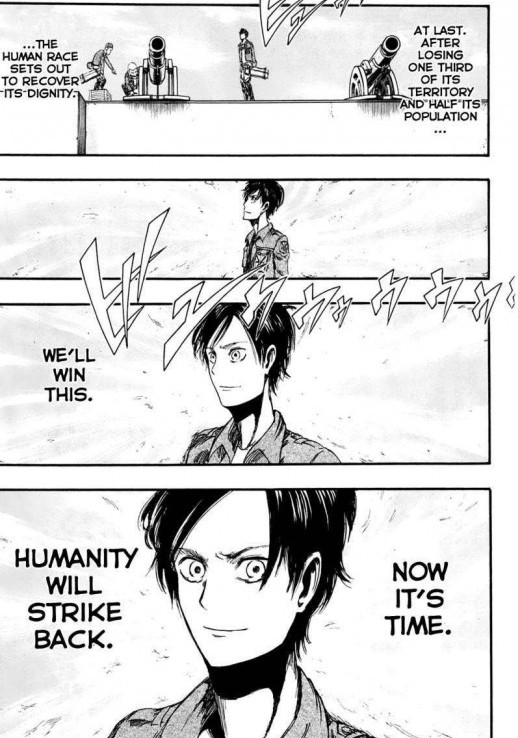

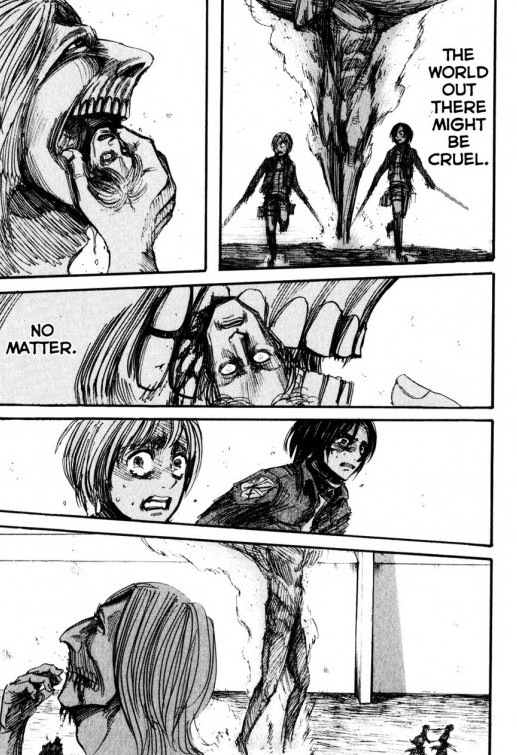

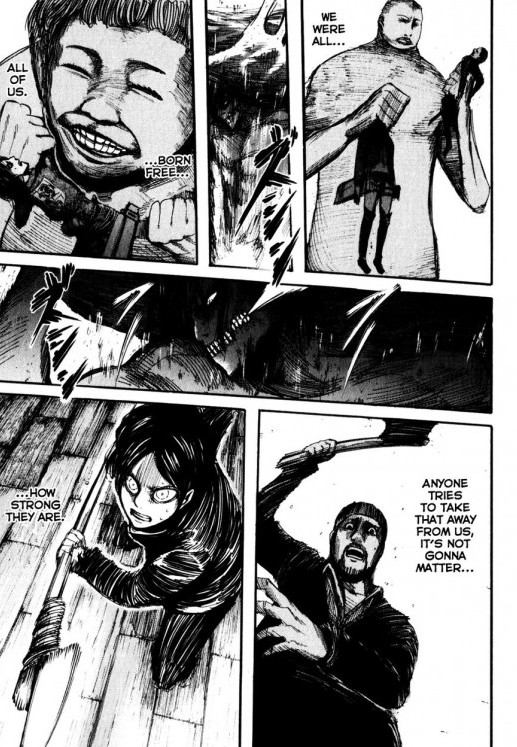

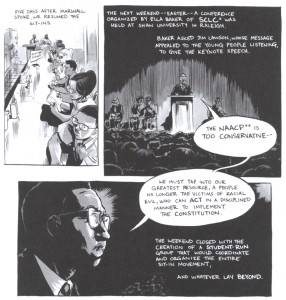

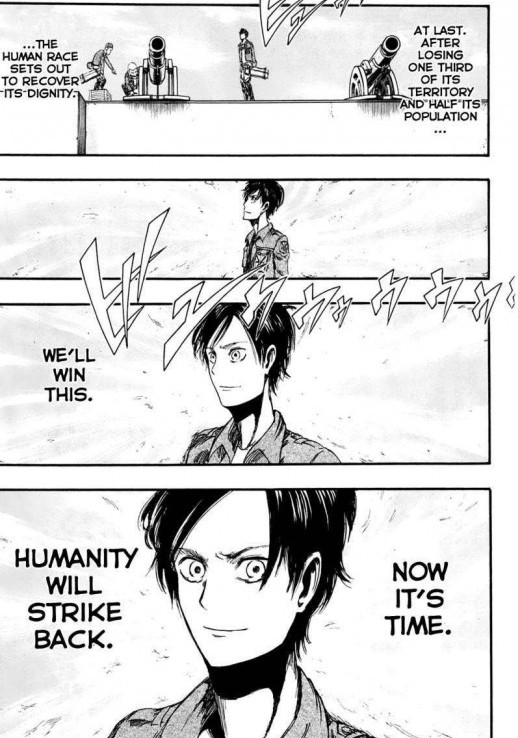

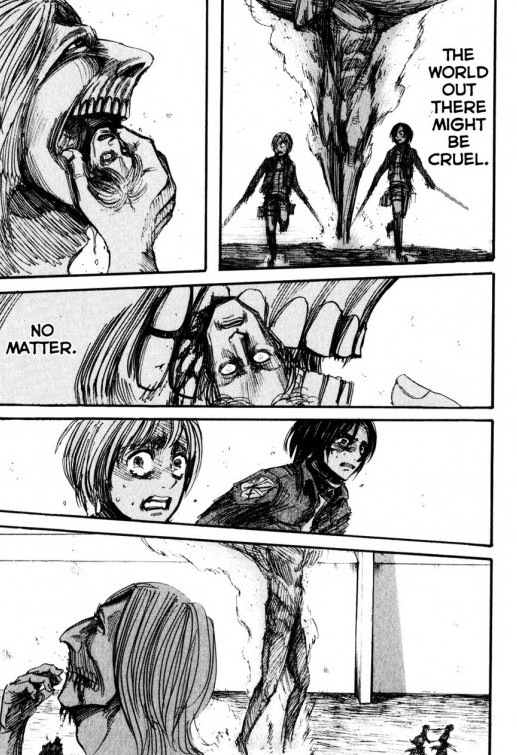

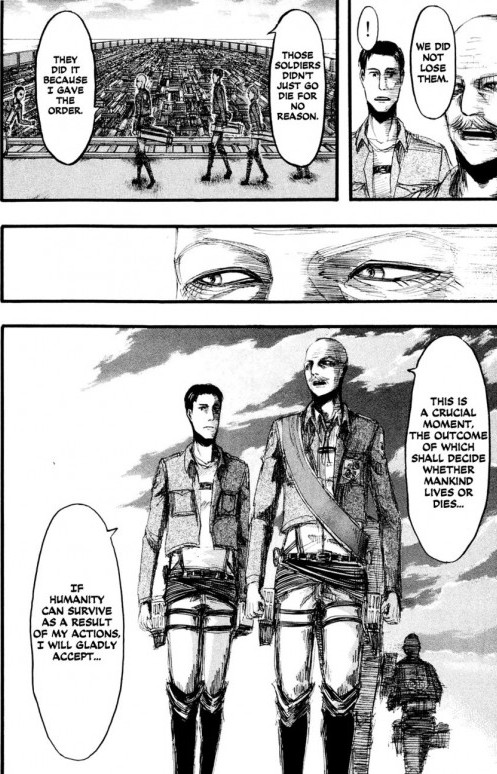

In the world of Attack on Titan, people are sometimes good, but just as often they are weak or venal. Additionally – and this can’t be said enough – the world is a cruel place. However, the cruelty of the world is no reason to stop fighting – if anything, it’s a reason to keep fighting:

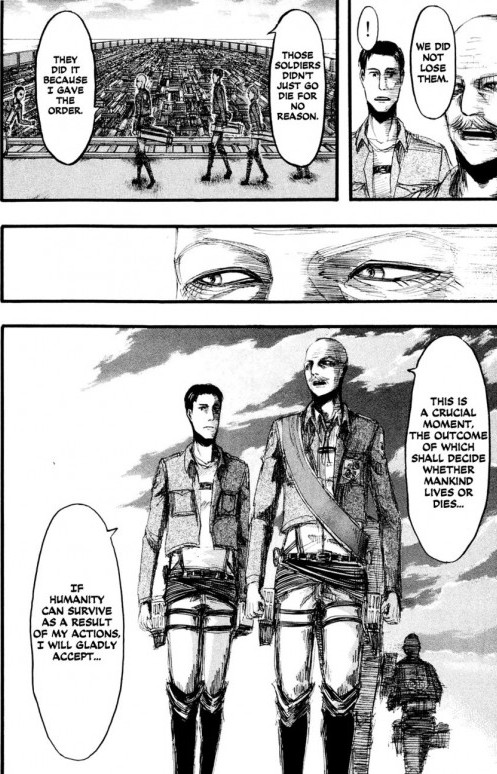

And yet, within this cruel world, people do their jobs quite well. Even more than Pacific Rim, with its ex-marine protagonist, Attack on Titan is oriented toward military values. The chain of command should be followed at all times; commanders are competent most of the time; to die for no reason is ignoble but death in service of the greater good is honorable; in order to make sure that death is not pointless, further deaths are required.

It seems obvious to me that this set-up – although it leans further toward the Abandon Hope All Ye Who Enter Here end of the horror-movie spectrum, and although it is far more pro-military than anything del Toro has ever made – would appeal to the guy who made Pan’s Labyrinth: fundamentally it’s a story of overcoming childhood trauma, and banding together to defeat nightmarish monsters who are almost, but not quite, human.

Because adult humans who are bigger and stronger than you are fucking scary when you’re a child, am I right?

It’s also clear why del Toro, with some very popular children’s movies to his name, would want to tell a more optimistic and less depressing version of this story about transcending abuse.

And while this might be a stretch, honestly the two series seem to have enough specific similarities that I’d bank on Attack on Titan being one of the properties that went into del Toro’s Japanese-monster-movie stew. It’s not even much of a secret, really: when the main character of Attack on Titan is Eren JAEGER and the robots that fight monsters in Pacific Rim are JAEGERS, surely we can acknowledge the possibility of a connection?

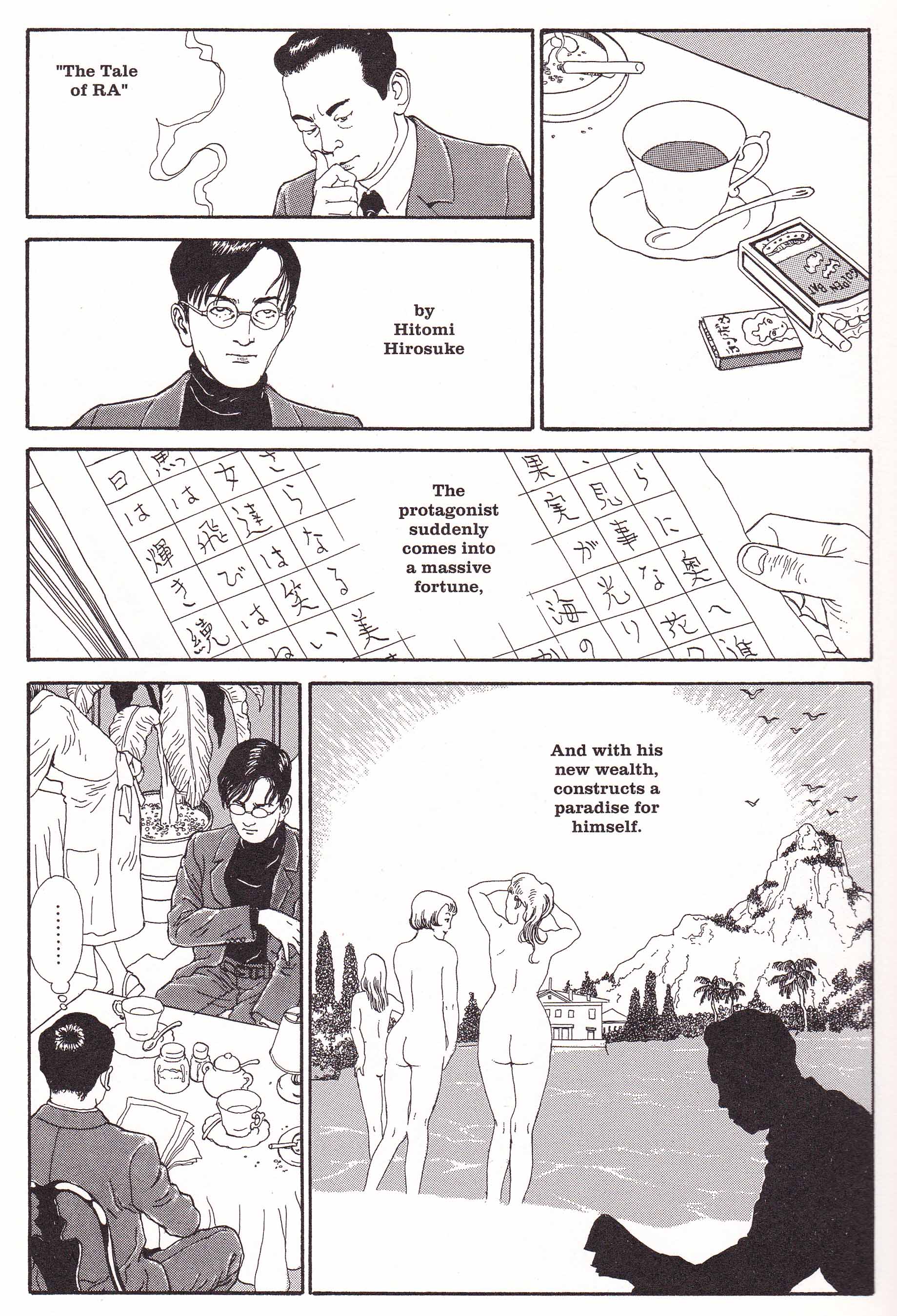

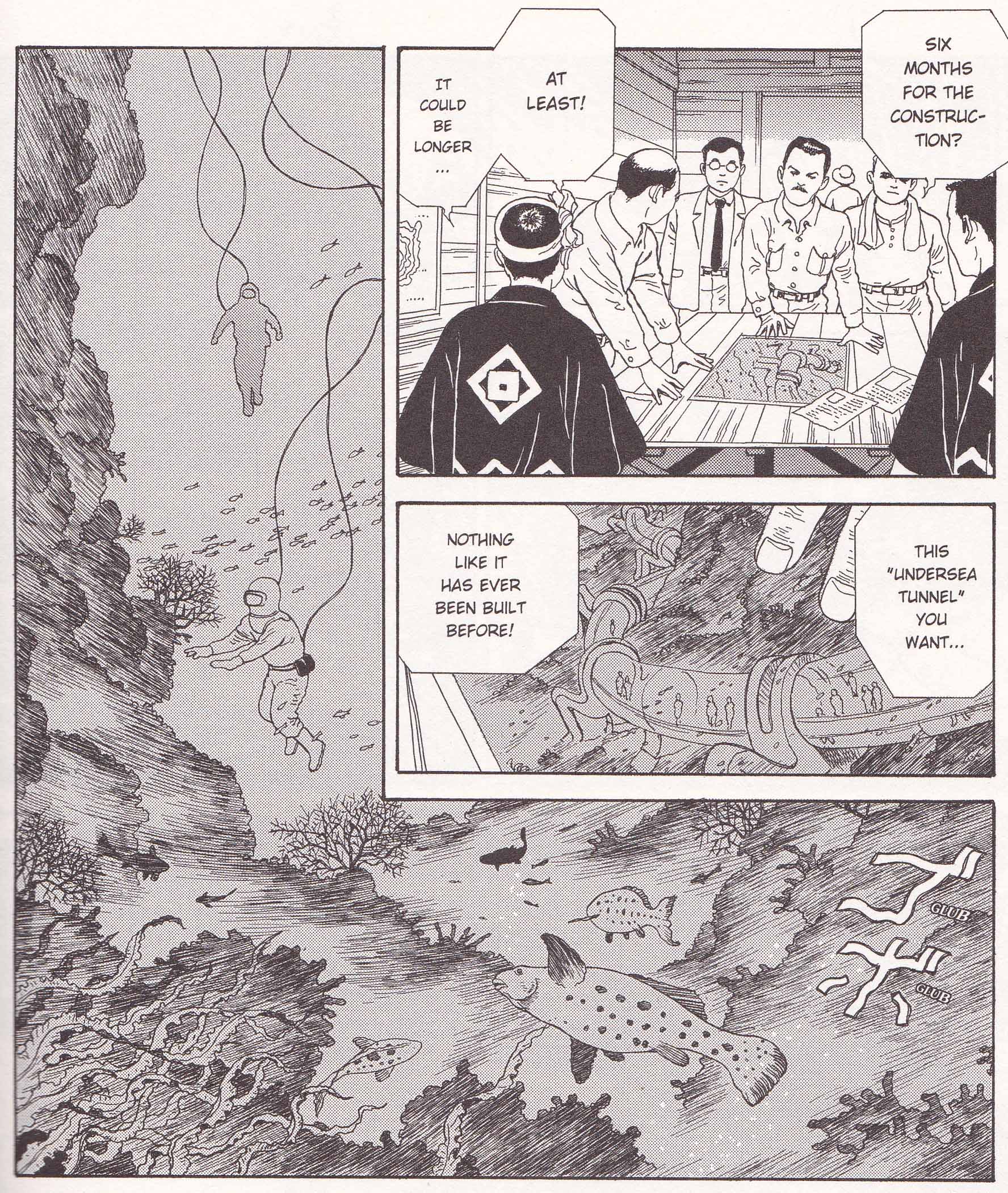

And that’s just to start with. This scene might be a bit familiar to anyone who’s seen Pacific Rim:

In Pacific Rim, Mako is a Strong Female Character: the only one to best the main character in a physical fight. She’s also the only Asian character with a speaking role, in a movie that owes an obvious and explicit debt to Japanese anime and monster movies.

One could argue that she is interesting because of her hand-to-hand combat skills; because her backstory is the best and most moving scene in the movie; because the actress who plays her is charismatic; because she occupies both the Strong Female Character role and the Properly Respectful Japanese Person role, as if to say that one can uphold the cultural role expected of one and yet still be a strong person at the same time.

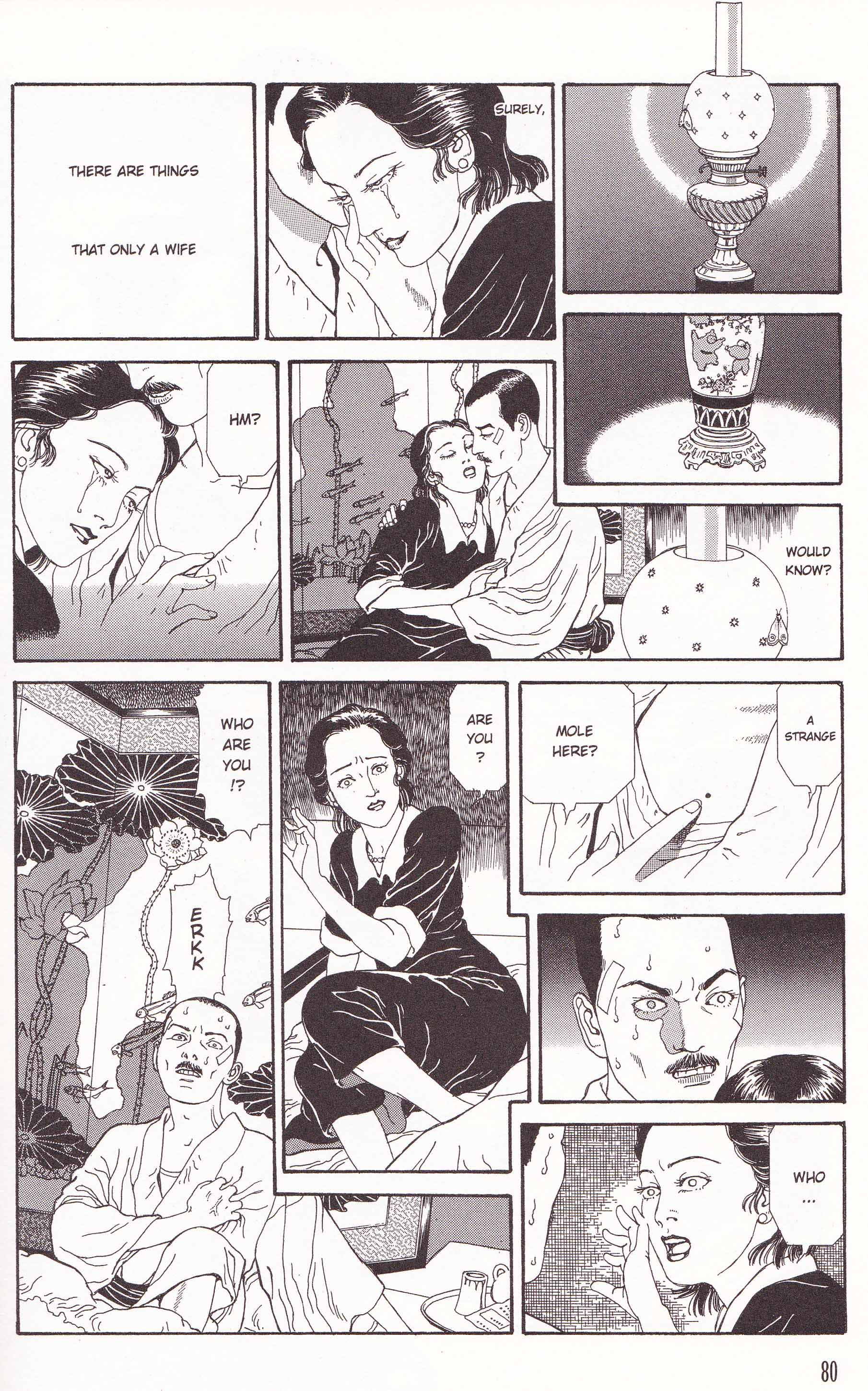

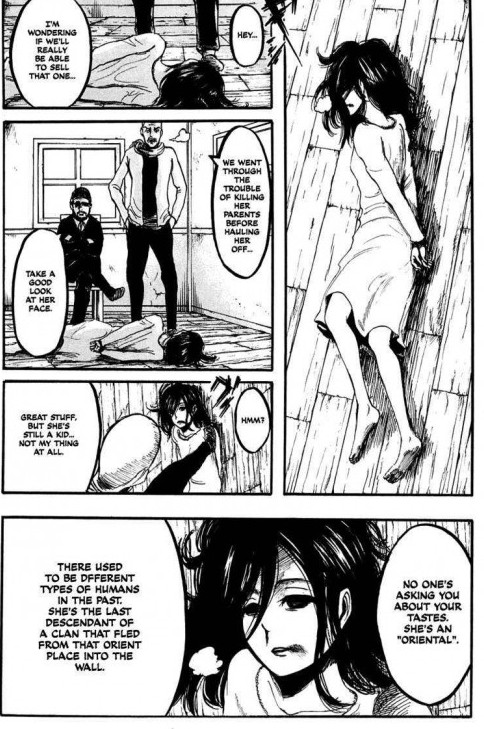

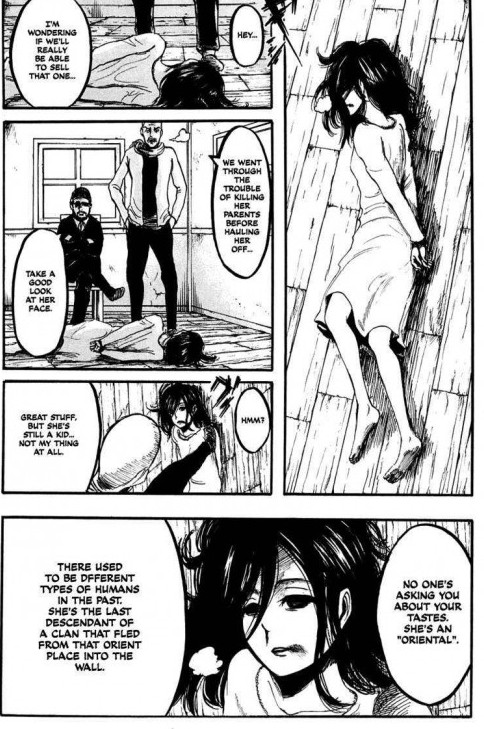

In Attack on Titan, the equivalent character is Mikasa. She is not just the only “Oriental” in the script, but in the whole world:

Given that both properties have an “the Asian bad-ass fighter chick” character, and given that I’m writing an article arguing for the superiority of Attack on Titan, and I don’t want to make it solely about the fact that I prefer thornier, more cynical and scarier stories, let’s talk about the treatment of female characters in each. Pacific Rim doesn’t only suffer from having a single female character with speaking lines; it suffers from the role that character plays in the story. Mako is attached to the commander of the Jaeger program because he saved her as a child; so is Mikasa is attached to Eren Jaeger. Looking similar so far – but why must Mako “belong” either to one man or another? Can’t she leave the protective custody of the father-figure without entering the protective custody of the suitor? Must women be passed from one man to another?

This isn’t a problem in Attack on Titan, not because Matsuko isn’t devoted to Eren – she is, pathologically so – but because there’s a diverse cast of female characters who are not all like her. In fact, the eccentric scientist who is a little too into the monsters is a woman – and not only a woman, but a female commanding officer!

The diverse cast of women belong to themselves, not to fathers or lovers. They’re explicitly on the same level as the male cast, fighters in the same unit of the army. The whole cast, male and female alike, share a comradely bond.

Speaking of comradely bonds, at first I thought that this series – humanity confined behind walls, lacking any way to proactively engage the enemy – might be a metaphor for a non-militarized Japan. It is, definitely, very pro-military, very pro-intervention, and very pro-violence. There are other hints of conservative thought, as well, starting from the author’s fundamentally mistrustful view of human nature.

Even disregarding the difference in worldview between Pacific Rim and Attack on Titan, though – because there are perfectly good reasons to prefer more a more optimistic narrative – Attack on Titan is the more thoughtful series, as well as the one that offers a more powerful social critique, despite being set in a stacked-deck fantasy world. The author of Attack on Titan is interested – not only in the mechanics of the fight or how the protagonists resolve their personal differences and come together to face an alien enemy – but also in the structure of the world. How do ordinary citizens feel about their taxes going towards a (seemingly useless) military? What is the incentive structure of the military, and how does it cause the best and brightest to avoid posts where they would do the most good? Is it always necessary for the minority to adapt to the needs of the majority? How does one bring about the social change one wishes to see in the world?

Of course, the series has flaws. It’s by no means trope-free, for one thing: from the dumb/suicidal shonen hero who is totally average except for his determination (to murder Titans); to the strong, silent warrior character who ensures that the main character can uphold his ideals; to the physically weak character who is nevertheless a genius strategist; there are plenty of stock characters here, too. Attack on Titan as well as Pacific Rim takes advantage of the hero’s fundamental vanilla-ness to give more spotlight to generally sidelined – but more competent! – supporting characters, which is a good and worthwhile trend I support (see also: Teen Wolf Season One), but why not take that extra step and remove the bland main character entirely?

So it’s not all gravy. And in some ways, the comparison is apples (Hollywood summer blockbuster) to oranges (Japanese manga and anime). But I’ll say it again: Attack on Titan is the stronger work.

Am I just a cynic? Do I prefer Attack on Titan because it is “darker” and (therefore) more “realistic” (as if there is anything realistic about giant monsters who eat people)? Or do I prefer it because it is, in my view, more complex, both in its characters and in the social structures they inhabit?

Maybe. I might be alone – at least among my friends – in my almost total disappointment with Pacific Rim. When even the positive reviews come with caveats that you shouldn’t “think too hard”, that you should “just enjoy the movie”, that monster movies “all about explosions”, that only “snobs” expect engaging characters alongside engaging fight scenes, however… it’s a sign that there is something amiss. I’ll stick with Attack on Titan, downer worldview, flaws, and all: at least it’s obviously the product of one person’s idiosyncratic worldview.

There’s something to be said for that downer worldview, anyway: when your protagonists are losing the battle at least half the time, their occasionally victories feel that much more earned, and sweeter.

_____

Again, Attack on Titan is available here