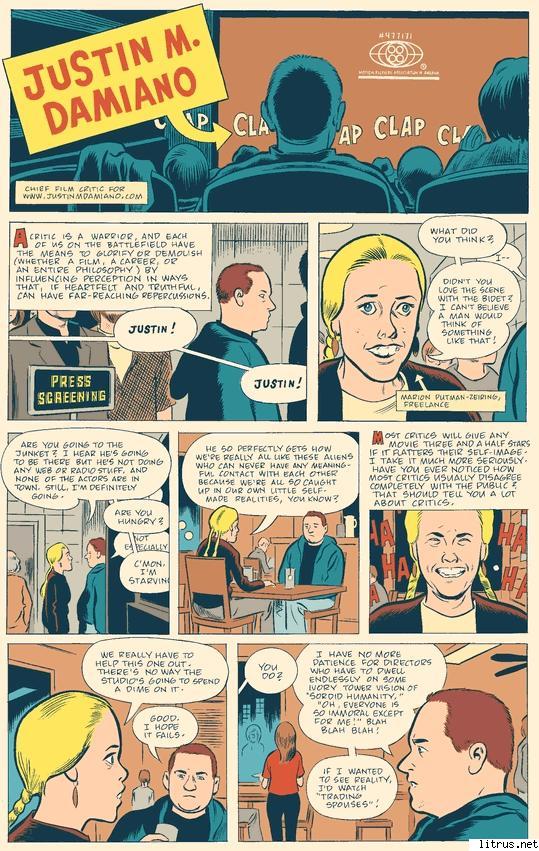

Justin M. Damiano was first published to limited notice in The Book of Other People (ed. Zadie Smith; full comic at link) in 2007. Its existence was jogged back into my memory by James Romberger’s recent review of The Daniel Clowes Reader where he calls it:

“…a classic that needs to be read by anyone who writes criticism on the internet.”

This wasn’t the way I remembered the story and I read it again to see if I had been blinded to its treasures on my first read through.

A number of critics have taken Justin Damiano to their bosoms, elevating the specific into a judgement of the whole or at least a comment on a significant number of online critics. At The Guardian, Peter Bradshaw suggests that:

“…mature, contemporary Damiano isn’t a cynic or a loser: he has transferred his idealism from the world of relationships to that of the cinema, and being an online critic, answerable only to himself, he is perhaps freer to express this pure, unapologetic idealism…Is Justin a sad sack for believing that this transcendence is to be found in the cinema rather than human relationships? Maybe – but not necessarily, and it isn’t clear that Clowes is inviting us to assume this.”

Another critic, Brian Warmoth, opines that:

“Clowes’ ability to distill the bitter side of humanity in menial activities and everyday labor or interests is extremely keen…It’s also about the rifts between critics and artists that can sometimes encompass shared ground.”

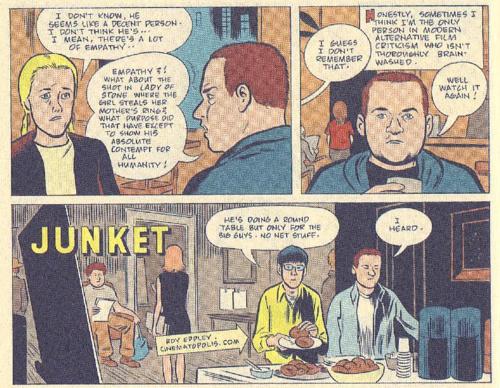

Part of this boils down to a presumption of antagonism—that artists are supposed to have a very low opinion of critics and criticism in general. It is easy to slip into this diagnosis unless one looks closely at the details of Clowes’ exposition, most of which holds very little water and specificity for critics. To suggest that Clowes was presenting a critique of critics in general here would be to do him a disservice and may even imply that he is a person of shallow intellect. Naturally the title of the anthology begs the question, “What other people?” It might be that the ultimate “other” for an artist is not his audience but his critics, but this wouldn’t be that much of a leap of the imagination for Clowes who has engaged in scathing criticism for years in the pages of his comics. Clowes isn’t so much an artist chastising critics but a practicing critic contemplating his own art.

Taking James’ premise as true, however, what exactly are the lessons we (as online critics, silent or otherwise) are supposed to glean from Justin M. Damiano?

(1) Critics have a overweening sense of self-worth.

Translation for comics-kind: A comics critic is a (part time) warrior, and each of us on the battlefield have the means to glorify or destroy (whether a comic, a career, or an entire philosophy) by influencing perception in ways that, if heartfelt and truthful, can have far reaching repercussions.

This sounds insightful (and damning) until you start replacing the word “critic” with other words like, “artist”, “cartoonist”, “director”, “journalist”, “politician”, and “pop star”. Basically anybody with access to the wider media through talent, money, or both. In this day and age, this would mean a television program, a newspaper, a studio, and, yes, a popular blog. There is very little doubt though that the comics critic is the dung beetle of this august list of movers and shakers.

(2) Critics enjoy toilet humor (or perhaps playful metaphors).

Well, they sort of do, and they’ve also shown some fondness for bidets apparently. A clear reference to Duchamp and his porcelain urinal but also a self-referential finger pointed at Clowes himself—a very arch critic in many stories in Eightball and a florid user of metaphor.

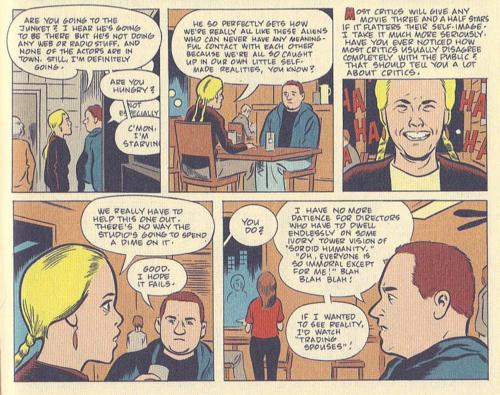

(3) Critics are self-absorbed and insular.

“He so perfectly gets how we’re really all like these aliens who can never have any meaningful contact with each other because we’re all so caught up in our own little self-made realities, you know?”

There’s an interplay between panels 2 and 3 on this page. The blonde girl, Marion, is the target of Justin’s irritable internal musings:

“Most critics will give any movie three and a half stars if it flatters their self-image…Have you noticed that most critics usually disagree completely with the public? That should tell you a lot about critics.” [emphasis mine]

That latter point is quite contrary to experience as a simple survey of the top 5 movies of the last two years will attest:

Top 5 movies by domestic gross 2013 with Rotten Tomatoes (RT) score

Iron Man 3 (RT 78%)

Despicable Me 2 (RT 76%)

Man of Steel (RT 56%)

Monsters University (RT 78%)

Fast and Furious 6 (RT 69%)Top 5 movies by domestic gross 2012

Marvel’s The Avengers (RT 92%)

The Dark Knight Rises (RT 87%)

The Hunger Games (RT 84%)

Skyfall (RT 92%)

The Hobbit (RT 65%)

Of course Clowes doesn’t mean any old critic. He means critics like Justin M. Damiano who is shown throughout this page in an act of self-condemnation, hurling stones at others while he sits in his own ivory tower of arrogance and recalcitrant elitism—the stuck-up loner with delusions of grandeur; the keyboard warrior of “modern alternative film criticism.” For all intents and purposes, this would include well over 50% of all comics critics.

But what exactly does “flatters their self-image” mean? One presumes that it means that critics tend to prefer movies which align with their own vision and experience of existence. Damiano suggests that critics should instead acquire a taste for other aspects of humanity as presented on film—those which run counter to their own beliefs. It should be stressed that we are specifically talking about “taste” and not action here, for Damiano is never shown acting on his preferences in art. Thus a critic with Randian principles should be able to develop empathy for the works of Vittorio De Sica. Similarly, a critic who abhors violence and misogyny should be able to appreciate and enjoy glorifications of the same. Since Marion is portrayed as a typical online critic, some might see this a proposition put forward by Clowes but this may not be the case. If Damiano is seen as a negative indicator (in some instances), it could also be taken as an admonishment of the critical community as a whole.

Marion’s comment that the film depicts human as “aliens who can never have any meaningful contact with each other” proves to be Damiano’s own “defect”—the very reason why he prefers “escapism” in film. The cinema becomes a brothel of whispered dreams and vicarious experience, a panacea for his lack of human contact. This explains his boredom when faced with Godard’s Le Mepris (a film about estrangement), a movie which probably mirrors all too accurately his own life. This isn’t so much Clowes needling critics so much as Clowes poking fun at himself, for his comics have consistently portrayed “sordid humanity” and immorality.

(4) Critics are mercurial and careless – “Good I hope it fails.”

But are they significantly more so compared to the general public?

(5) They don’t suffer fools gladly – “Well watch it again!”

(6) They are frequently jealous of access.

See point 4.

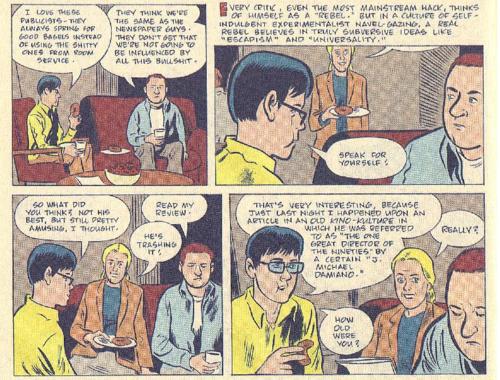

(7) “Every critic, even the most most mainstream hack, thinks of himself as a “rebel.” But in a culture of self-indulgent experimentalist navel-gazing, a real rebel believes in truly subversive ideas like “escapism” and “universality.”

This isn’t as straightforward as it sounds. Damiano suggests that every critic considers himself a “rebel,” which would make him a rebel himself. Rather than promoting “bidet” art, Justin has taken his beliefs one step further and is rebelling against rebellion—championing “escapism” and “universality.” In other words, the act of criticism is seen here not so much as an act of connoisseurship but a process of self-promotion and self-aggrandizement which has little relation to “taste” or the object beheld.

At this point, alternative comics criticism and film criticism diverge, at least in the American sphere. The gradual migration of superhero fans into alternative comics has led to a renewed interest in objects of times past and the assimilation of tropes and techniques associated with superhero comics and other forms of commercial art. Further, this might be an area where comics have a leg-up according to Justin Damiano’s injunction. The 5 nominees for Best Continuing Series at the 2013 Will Eisner Awards were Fatale, Hawkeye, The Manhattan Projects, Prophet, and Saga—all firmly lodged in the realm of of “escapism.”

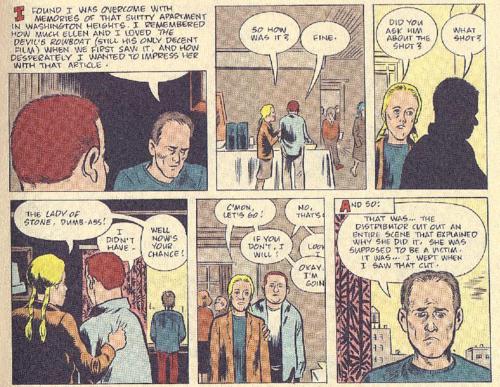

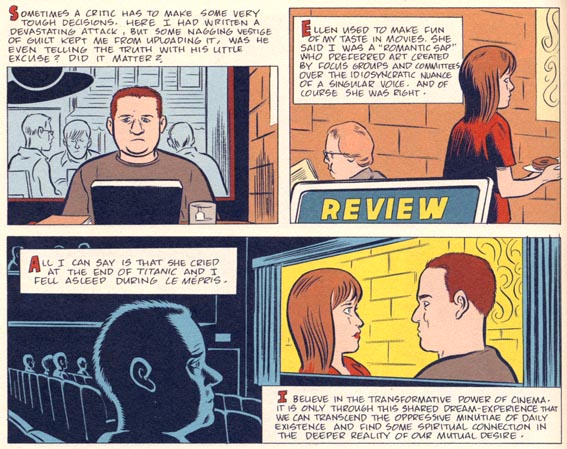

(8) Criticism is autobiographical and self-revelatory.

“I remembered how much Ellen and I love The Devil’s Rowboat…and how desperately I wanted to impress her with that article.”

In the first panel of this page, Damiano’s thoughts completely obscure the words of the director who bears a vague resemblance to a balding Clowes (well, it could also be Gary Groth). One might say that his own thoughts take precedence over the ideas of the director being interviewed; a point further emphasized by the revelation that a favorite scene of his from an earlier film of that director was quite unintentional (the result of a distributor cut).

This seems like a knock on critics but it actually suggests that criticism is as much an act of creativity as the production of a film or comic—a metatextual comment on the object being read. The real mark of bad criticism in my view is “objective” synopsis. I wouldn’t read criticism if it all read as if it was produced by a machine (or a marketing agent).

(9) Critics are frequently loners with poor social skills.

“I believe in the transformative power cinema. It is only through this shared dream-experience that we can transcend the oppressive minutiae of daily existence and find some spiritual connection in the deeper reality of our mutual desire.”

Justin is looking at a pictorial representation of a cinema screen which is actually the fourth panel of the comics page. This is probably a reference to Clowes’ own migration to and from comics and film.

Clowes’ cynicism is so thoroughly ingrained into his comics that the somewhat ambiguous but treacly conviction stated here would quickly arouse the suspicions of his long time readers. One imagines that some people feel the same way about the films they see, but this seems like a specific interjection clarifying the state of mind of our protagonist, a point reasserted on the page following where he thinks:

“When Ellen finally left, she said she felt as though she didn’t even know me. She said I lived entirely inside my own head.”

The escapism which Justin seeks in the cinema (and art) has become a substitute for any real real connection. Any warmth in expression (the bottom panel bears his least contemptuous face) or speech is reserved for the figures he sees on the cinema screen. He has nothing but distaste for the people he interacts with in the pages of this comic.

It seems to me that whatever observations Clowes makes about critics are simply a side effect of using a film critic as the main character of his story. Any bitterness or acute observation is restricted to the first half of the story and forms the bedrock for his elaboration on the protagonist later in the tale. The further one delves into Justin M. Damiano, the less it reads like a standard exposè on the failing of critics, and the more it feels like a story about a man who just happens to be a film critic. In this way, it has many similarities to one of Clowes’ earlier works, “Caricature”, which constantly straddles the line between reality and illusion in its portrayal of a caricaturist—a competent loner working the crowd and his sexual proclivities.

But even more than in that work, Justin M. Damiano turns in on itself, becoming a moment of self-criticism and reflection; a careful dissection of his own comics. The “other” of the collection’s title (The Book of Other People) is not so much his critics or his audience—they remain anonymous and unknowable. The “other” is the person that he can never hope to become.

Honestly, I was thinking mostly of the button.

I think this is completely confused.

“To suggest that Clowes was presenting a critique of critics in general here would be to do him a disservice and may even imply that he is a person of shallow intellect.”

This would be true if the story were an attack on criticism as Noah assumes. The point is that Justin M. Damiano is not a critic but a poor substitute for one. Notice how his estimation of the director’s art boils down to a “shot” in an earlier film which “proves” the director’s “absolute contempt for all humanity.” That Damiano has pounced on a detail is evident in its not even being a scene but a “shot,” and his friend’s inability to recall it. Nor is it a judgement of the director’s work (which Damiano “has no patience for”) but a dubious assumption about the director’s motives. And his interpretation is corrected: the director explains “an entire scene” contextualizing that shot was cut against his will, but Damiano’s internal narrative- his doctrinaire rejection of film as an attempt to engage with reality, and primarily his disappointed personal life- overpowers the “nagging vestige of doubt” this gives him.

“[Damiano’s opening narration: ‘A critic is a warrior…’] sounds insightful (and damning) until you start replacing the word “critic” with other words like, “artist”, “cartoonist”, “director”, “journalist”, “politician”, and “pop star”. Basically anybody with access to the wider media through talent, money, or both… there is very little doubt though that the comics critic is the dung beetle of this august list of movers and shakers.”

If a comics critic is marginal it’s because he covers a marginal form, particularly when it comes down to the small press, independent comic, and a critic’s power to significantly affect the fortunes of such a work is realistic. Damiano decides the fate of a film which is marginal and struggling: his friend says, “We really have to help this one out. There’s no way the studio is going to spend a dime on it,” and the director appears gaunt and sickly. The point of Damiano’s self-image as a “warrior with the power to demolish a film or a career, uploading fifty unstoppable megatons of himself into the ether” is that it’s a crude, dangerous concept of criticism. There’s no discussion of enlightening, exploring, or learning. Such a self-description wouldn’t make sense for an artist other than a Thomas Nast-style caricaturist, and any journalist or politician who described himself that way would sound equally ominous.

“[Damiano’s dismissive remark about critics: ‘Most critics will give any movie three and a half stars if it flatters their self-image… Have you noticed that most critics usually disagree completely with the public? That should tell you a lot about critics…’] is quite contrary to experience as a simple survey of the top 5 movies of the last two years will attest… But what exactly does “flatters their self-image” mean? One assumes it means critics tend to prefer movies which align with their own vision… Damiano suggests critics should instead acquire a taste for aspects of humanity as presented on film which run counter to their own beliefs…”

Damiano is talking about elitist critics who champion obscure art-house films which don’t connect with the public, and sees those critics as favorably acceding to films which flatter their elite self-perception. Your inference that he wants critics to engage with challenging aspects of humanity would be terribly ironic coming from him, but there’s no evidence for it. Damiano demands that film align with a collective ideal and doesn’t want to see any challenging aspects of humanity presented on film.

I think Clowes would view those Rotten Tomatoes scores, coming from an internet-based, democratized service, as including a heaping helping of Damianos, and indeed when you dig into the “top critics” rating for that kind of film it’s always lower. I doubt the New Yorker, for example, cared for any of those films, and Damiano has ivory tower elites in his sights. Clowes draws a distinction between Damiano as a creature of the internet and critics from traditional media (agree or disagree, this is his clear qualitative judgment) and Damiano styles himself as a champion of the common man.

“It should be stressed that we are specifically talking about “taste” and not action here, for Damiano is is never shown acting on his preferences in art.”

Er, no, the whole story builds to his demolition of a film with the click of a button. I see what you’re trying to say, but it rests on the confused assessment above of what Damiano wants.

“[We glean that] criticism is autobiographical and self-revelatory… [Damiano’s self-absorption] seems like a knock on critics but it actually suggests that criticism is as much an act of creativity as the production of a film or comic… The real mark of bad criticism in my view is “objective” synopsis. I wouldn’t read criticism if it all read as if it was produced by a machine (or a marketing agent).”

Damiano’s review/blog post is a “creative act” that overpowers another work struggling to be heard. Clowes isn’t suggesting criticism should be a mechanical synopsis, he’s calling for honest, personal engagement with the art on trial. As an unchecked ego, Damiano has no difficulty with the personal element, but he fails at the engagement.

“Clowes isn’t so much an artist chastising critics but a practicing critic contemplating his own art… [Damiano’s preference for escapism] isn’t so much Clowes needling critics as Clowes poking fun at himself, for his comics have consistently portrayed “sordid humanity” and immorality… [Damiano’s fantasy image of his cinematic ideal] is probably a reference to Clowes’ own migration to and from comics and film… The further one delves into Justin M. Damiano, the less it reads like a standard exposè on the failing of critics, and the more it feels like a story about a man who just happens to be a film critic… even more than in [Caricature], Justin M. Damiano turns in on itself, becoming a moment of self-criticism and reflection; a careful dissection of his own comics.”

Damiano is one of Clowes’ most deeply unsympathetic characters and from all evidence a dedicated enemy of everything he stands for. It’s very difficult to read the story as self-criticism and reflection on Clowes’ part- and not even an unwitting self-portrait, but a “careful dissection!” There’s no basis for interpreting the image of Damiano’s cinematic ideal (him watching a heroic version of himself gazing into the pretty barista’s eyes onscreen) as a reference to Clowes’ film and comics career; it’s an image of the character’s credo, and his folly. If anything, the story’s flaw is that Clowes doesn’t always inhabit Damiano convincingly; he has him saying more discrediting things than a person would say about himself.

“Naturally the title of the anthology begs the question, “What other people?” It might be that the ultimate “other” for an artist is not his audience but his critics, but this wouldn’t be that much of a leap of the imagination for Clowes who has engaged in scathing criticism for years in the pages of his comics… the “other” is not so much his critics or his audience—they remain anonymous and unknowable. The “other” is the person that he can never hope to become.”

The connection with the title “The Book of Other People” is obviously Damiano’s solipsistic failure to engage, with the artist’s perspective or anyone else’s, and the belligerent self-absorption of internet culture in general. Clowes’ starkest “other” in the present cast is Damiano, but Damiano is clearly the subject as a critical disaster and a herald of a cultural crisis.

“This would be true if the story were an attack on criticism as Noah assumes. ”

I don’t think I assumed anything about the story? I saw the quote you took out of context and responded to that. But I haven’t read the story.

Though Suat’s reading does make the comic sound somewhat interesting. I’m afraid I agree with him that your take, with the rigid distinction between critic and artist and the banal moralizing, gives Clowes a lot less credit.

Whatever credit it gives him, am I right or wrong? Don’t strain yourself or anything, but Tong did link to the whole story online.

FYI, Suat’s given name is Suat; family name is Ng.

I think Suat’s probably right. Anxiety about his relationship to popular art runs throughout Clowes’ work. Given that, I find it hard not to see the main character here as at least in part an analog for Clowes himself.

So, yeah, I think Clowes is smarter than you’re giving him credit for.

Well, God bless.

Deelish – “The point is that Justin M. Damiano is not a critic but a poor substitute for one…and primarily his disappointed personal life- overpowers the “nagging vestige of doubt” this gives him…[]…Clowes isn’t suggesting criticism should be a mechanical synopsis, he’s calling for honest, personal engagement with the art on trial.”

Damiano’s response is as honest as it gets – it comes deep from within his soul. Which doesn’t mean you have to like it or anything. I don’t think Clowes is that interested in writing one note characters. Damiano has traits which suggest that he’s not a particularly good or fair critic, but there are parts of him (especially in the latter half of the comic) which suggest that he could be one if he wanted to be. I’m giving Clowes the benefit of the doubt here. I’m assuming that he’s aware of the rich history of criticism which suggests that the deeply personal has everything to do with criticism (and art if you want to make the distinction) – hence Noah’s Baldwin (Devil Finds Work) example.

Clowes often presents caricatures of himself in his comics whether in his straight criticism or fictional narratives like Ghost World. In Ghost World, he appears not only as a character but as a facet of Enid who is endlessly cruel about the people she observes. It’s not hard to see that cinema-panel as being a reflection of Clowes’ own proclivities. He’s not a mirror image of Damiano – he’s married for one thing which means he’s made a human connection. But the work of a cartoonist is often as solitary as that of a blogger. There’s a coldness in much of his work – the warmth of Damiano’s cathartic screen fantasies are exactly what most of his comics lack. His somewhat sentimental internal musings on the power of film are precisely what Clowes won’t allow himself without the distance of character. Clowes criticism in comics form is frequently harsh but never specific – does this make him sensitive or cowardly? Seen in this way, his character Wilson (from the comic of the same name) is in part wish fulfillment.

Deelish – “Clowes’ starkest “other” in the present cast is Damiano, but Damiano is clearly the subject as a critical disaster and a herald of a cultural crisis.”

Yeah, I really don’t think Clowes is at that level. But you could be right. I may be giving Clowes too much credit if he actually thinks critics like Damiano herald a “cultural crisis,” and is wringing his hands or poking fun at them in this instance.

“Damiano’s response is as honest as it gets – it comes deep from within his soul.”

I think Clowes would agree.

“I’m assuming [Clowes is] aware of the rich history of criticism which suggests that the deeply personal has everything to do with criticism (and art if you want to make the distinction)…”

Yes, but like I said, the problem is not that Damiano’s response is personal, but that it’s not really a response. Criticism is not a new work of fiction. Clowes portrays one creative work demolishing another, which is made possible because one is delivering a verdict on the other in the court of public opinion.

Would you agree that the critic has a moral obligation to his or her subject? When Noah writes this about Ghost World:

“Sadism is about control. As such, it’s often about fantasies of actually inhabiting or being the other person. So imagining someone as your alter ego can be a way to inhabit them and destroy them. Basic rape fantasy.”

https://www.hoodedutilitarian.com/2012/01/what-does-that-even-mean/

Should we evaluate it the way we would evaluate a Hannibal Lecter novel, or does he have some obligation to Clowes?

“Criticism is not a new work of fiction. Clowes portrays one creative work demolishing another, which is made possible because one is delivering a verdict on the other in the court of public opinion.”

Well, I think Noah has answered this already in the Megareview thread where he writes that, ‘“The Devil Finds Work” is totally harnessing a series of films to his own interests and concepts; his personal background and his analysis is way more important than the artwork he’s talking about.’ To be more specific, I would say that Baldwin’s reading of The Exorcist is one of the strangest, out of left field things in the book. I would never have thought of it with my background.

You’ll have to clarify that “moral obligation” comment. I’m not sure how Noah disobliged Ghost World or its author. By not reading it the correct way?

I really don’t think critics have an obligation to the creator they’re writing about. They have an obligation to truth, or beauty, or whatever it is artists or creators have an obligation to. I guess that comes around to being a duty to the creator in question as well as to the audience. I would feel like I was doing Clowes a disservice if I pretended I thought that Ghost World was not sadistic when I think it is, or if I pretended that his take on teen girls was original or thoughtful. I’d feel I was doing a disservice to him, too, if I pretended that I thought his take on criticism was as simple-minded and silly as you seem to want it to be. I mean…couldn’t you see your determinedly straight-forward, un-layered meaning as demolishing Clowes’ work in the court of public opinion (whatever that means when we’re talking about a comment thread on a fairly obscure blog)?

I think Baldwin’s reading of the Exorcist is glorious, though I actually like the film a good bit more than he does. But his reading makes me appreciate it more, and certainly his reading is a greater work of art than the film in question (which, as I said, I quite like.)

Oh…and I’ll admit that (in line with my appreciation of horror film) I quite like destructive criticism and destructive art (to the extent they can be separated.) There’s nothing holy about creation; creators don’t deserve any more respect than anyone else standing in the public square yodeling to get your attention. Lots of art sucks and should be pissed on. To paraphrase Laura Mulvey, the critic’s goal is to destroy pleasure.

Where’s that from – I mean the Mulvey thing.

On the other hand, do you think you should have recused yourself from the Chicago Clowes gallery exhibit? Was your assessment a foregone conclusion or did you think looking at the original art would change your mind about Clowes? Part of your try, try again philosophy.

Oh, I see it was about “male pleasure” and Hollywood.

“It is said that analyzing pleasure, or beauty destroys it. That is the intention of this article.”

I don’t really see why you shouldn’t write about something you dislike, any more than it would be wrong to write multiple pieces about an artist you like.

In fact, as it happens, I didn’t pitch that review. The Reader asked me if I wanted to write about it. I said, well, I’m not a big fan of his, but if you don’t mind that, sure. And I was curious how they’d handle dealing with his work in a gallery setting. It also seemed like an opportunity to read a bunch of his comics and see if there was anything I liked more than I liked Ghost World. And I did find Death Ray somewhat better, so not a total loss.

The last panel might also be a Nabokov reference. There’s a scene in Laughter in the Dark where the characters (one of whom is an art critic) watch a movie apparently depicting the book’s closing scene.

Suat, Baldwin still deals with The Exorcist. He shows that the film has an impoverished concept of evil.

“You’ll have to clarify that “moral obligation” comment. I’m not sure how Noah disobliged Ghost World and its author. By not reading it the correct way?”

I mean being personal and creative is not the only measure of criticism. Noah’s vision of Clowes doesn’t only have to be interesting or “so Noah,” it has to build a convincing case from the evidence. If we’re to make allowances for idiosyncratic interpretation or poetic truth, how much?

The critic has a moral obligation not to misrepresent his subject. Clowes complained about critics having “an agenda that has nothing to do with an honest response to what they’re looking at” and “settling some unspoken score.” When Baldwin had a problem with representations of race on film, he didn’t look for other ways to get back at the filmmakers, he wrote about representations of race on film.

Noah: “I’d feel I was doing [Clowes] a disservice if I pretended that I thought his take on criticism was as simple-minded and silly as you seem to want it to be. I mean…couldn’t you see your determinedly straight-forward, un-layered meaning as demolishing Clowes’ work in the court of public opinion?”

I’m disputing claims that Suat is making about the straightforward, top-layer meaning, not writing my own review. He’s talking about text, he hasn’t gotten to subtext. This is a twist you attempted before:

“I don’t entirely understand why you think that flattening [Wilson] and robbing it of ambiguity is defending [Clowes]. But perhaps you’re not defending him? I guess you could be telling me that I’m giving him too much credit….”

Your interpretations of Clowes as a sadist do not allow his work complexity. They treat his comics as simulacra of literature, pointing every element inward to a simple narrative about the author’s self-gratification that you admit is “boring.” With Justin M. Damiano, you and Suat are trying to neutralize a story that is obviously an attack on internet critics by calling it a self-portrait (not even /also/ a self-portrait, just a self-portrait). You both threaten that accepting its plain meaning will reflect badly on Clowes, instead your version is better. The story is bad if it’s about critics on the internet and better if it’s about himself. There’s something passive-aggressive about that.

“Oh…and I’ll admit that I quite like destructive criticism and destructive art (to the extent they can be separated.) There’s nothing holy about creation; creators don’t deserve any more respect than anyone else standing in the public square yodeling to get your attention. Lots of art sucks and should be pissed on.”

I wouldn’t necessarily mistrust a critic who talked about criticism as destruction and said he enjoyed it. It would depend on his criticism. If he invokes the great 19th century novelists to put a work in its place, it might be crude (because the next great thing will rewrite the rules) but at least it’s credible as long as he applies that standard consistently. If he trawls minutiae and twists a comic into pretzels to accuse the artist of figurative rape, his feminist zeal loses credibility when he dismisses his critics as “butt-hurt.” If he throws all the trappings of academia into an attack with no respect for their meaning, he reveals a disinterest in criticism.

You’re attacking me personally for being tendentious by saying I attack creator’s personally by organizing evidence tendentiously.

It just boils down to you not agreeing with my readings, as far as I can tell. Which you’re absolutely entitled to do, obviously.

I still don’t get how robbing Clowes of complexity is a compliment to him. But if you think you’re flattering him by pretending he’s simple-minded, that’s fine.

It’s pretty obvious this comic about internet critics is really a comic about internet critics. It’s consistent with his worldview in Pussey, The Death Ray, and Art School Confidential. It’s clear (from, most explicitly, the intro comic to Pussey, where Clowes laments the current nerdy state of pop-entertainment) that Clowes thinks the comics nerd-culture adores are shallow and meaningless. In Pussey he made fun of a loser whose only ambition in life was to imitate other shitty comics artists, in this comic he makes fun of someone who adores mainstream movies and does his best to malign ‘real’ art. I don’t think taking this critique at face value does Clowes a disservice. It’s one of the major themes to his work; inauthentic art and people are shit. His Ghost World characters hate inauthentic shit, his Art School Confidential Character hates what he (and probably Clowes) see as the artificial, empty fine art world, and the Death Ray is about how stupid the worldview behind superheroes is when someone tries to make it work in the real world.

Clowes also populates his world with characters who are dishonest to themselves or others, artists who aren’t very good, but at least they are earnest, and I think this probably reflects how Clowes sees himself. I think Clowes is clearly the director, also making movies about how people ‘can never really communicate’. The director as an artist is sort of an acerbic jerk but he has a sentimental side, something that’s obvious about Clowes the artist if you get to the end of most of his comics (excepting the Death Ray for one, which is probably his strongest.)

There is some Clowes in Damiano, (he’s a bad [critic], but at least he’s earnest) just like the Caricature character, or Wilson, or Random Wilder in Ice Haven, or Pussey in Pussey. But while Clowes is generous enough to the objects of his scorn to give them an inner life, I don’t think there’s really any doubt that most of these characters and what they represent are supposed to be worthy of contempt.

I’m not disagreeing with you, Isaac.

His Ghost World characters start out hating “inauthentic shit” but then they grow up and realize that there’s more to life (and people) than “inauthentic shit.” Art School Confidential laments the “artificial, empty fine art world” and grown up Clowes proceeds to insert himself into the institutions which prop up that world (the university, the gallery). The Death Ray suggests how stupid superhero tropes are, then uses this to reflect human interaction and weakness, and the allure of escapism.

Clowes is the director and the critic in Justin M. Damiano. Damiano isn’t simply a self-obsessed internet critic but a study of Clowes’ own deficiencies. The straight up scorn is something he’s gradually left behind – a boring remnant of what was demanded of him when he was viewed as part of the “After-Underground” generation. He’s grown into a considerably more complex narrator than the practitioners of those days.

Why I Hate Christians was actively self-critical. Young Dan Pussey was a self gone in another direction; he even had Clowes’ first name. Enid in Ghost World is shown being nasty and hypocritical from the beginning.

An author inhabits all his characters. That doesn’t mean the conclusion that he’s talking about himself is always reliable, or that arguing with it necessarily diminishes the work. Clowes portrays the internet empowering a new breed of critic who attacks art for accurately portraying his condition and for interfering with his immersion in mass-media escapism. Your gesture toward complexity doesn’t address the way you devalue that scenario, and the narrative you produce (cartoonists are solitary; Clowes yearns for the big, emotional experience of cinema not provided in his comics; as a fiction writer, Clowes is a coward who wishes he could name names like Damiano) is not self-evidently more rewarding.

Damiano is not a work of straight-up scorn because Clowes endeavors to get into the character’s head and learn what makes him tick. If it is best understood as a portrayal of Clowes, a reading that also deserves self-examination and self-criticism, we have to look at what Damiano does, and not evade the narrative we’re given.

Maybe it would help if he changed the names to make it a review of Shia’s film.

I also am not satisfied as to the reasons this comic is judged as moronic in reference to internet pundits but praiseworthy as a “study of Clowes’ own deficiencies”. Tong’s tactics seem like a veneer of intellectualism over the schoolyard rejoinder “I know you are, but what am I?”