A review of Tropic of the Sea

The manga is by Satoshi Kon and that’s probably as much information as most people will need to make a purchasing decision. The forgetful will receive this gentle prod—Kon is the late writer and director of movies like Millennium Actress (2001) and Paprika (2006).

One should never read an afterword before experiencing the work being described but for the purposes of this review it proves somewhat enlightening. For one, Kon was embarrassed by this early work of his (first published in 1990 in Young magazine, and republished in 1999 and 2011) and even considered redrawing it in its entirety. The serialized parts were drawn under extreme time pressure and this is evident in the plotting and pacing if not so much in the actual draftsmanship.

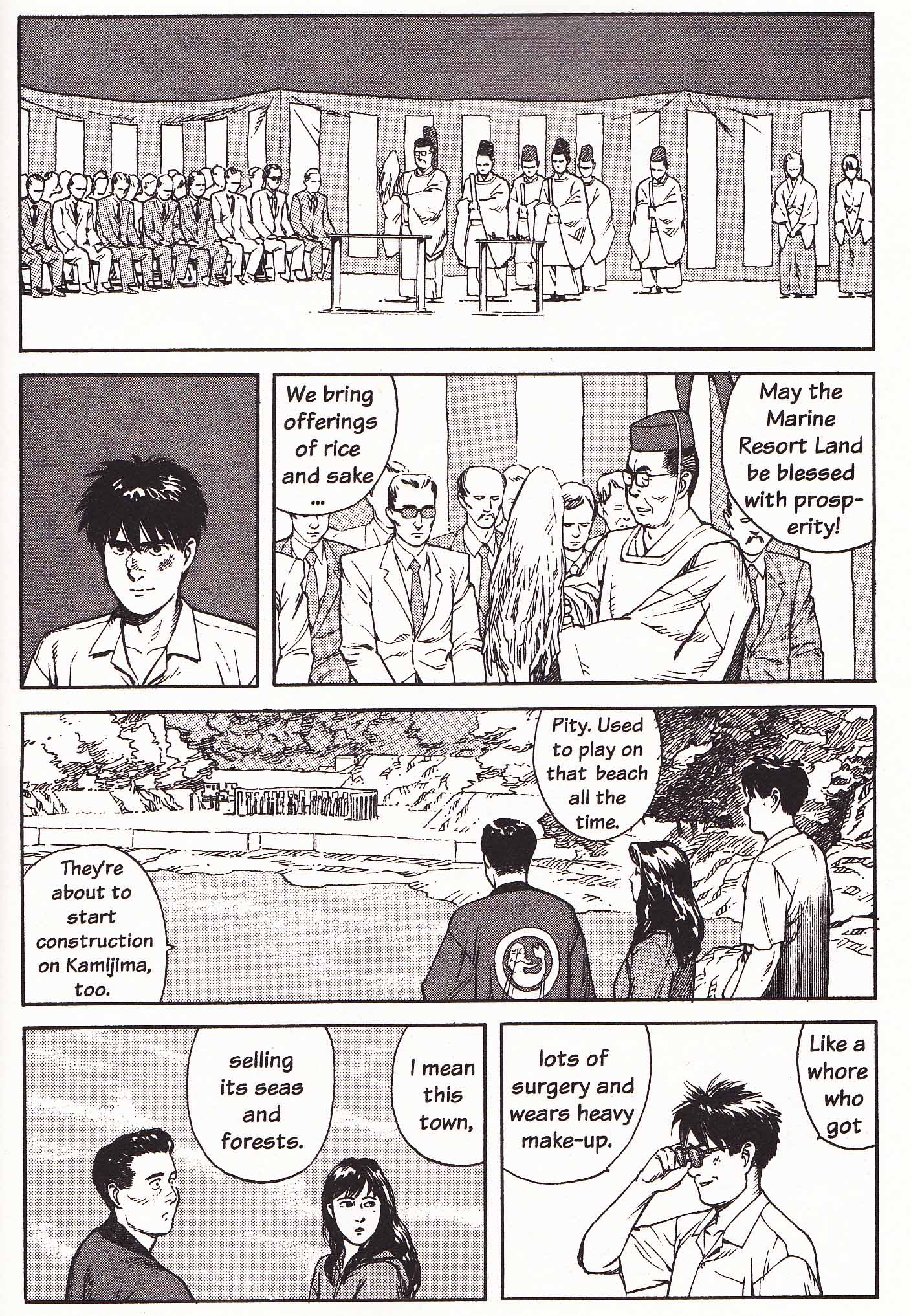

No wonder then that the comic proves to be a standard moralistic pot boiler about abandoning the old ways of Shinto (and living in symbiotic harmony with nature) in favor of modernization and worshiping the works of Mammon. It all does sound a bit Miyazaki-ish but done with considerably less grace. The father of the young protagonist (Yosuke) is a Shinto priest and mermaid’s egg curator—a descendant of a long line of priests charged with protecting a mermaid’s egg which they release into the wild every 60 years. As with many family friendly Asian pop culture products, he’s not a complete douche but someone who has lost his way due to a family tragedy—his wife drowned and could not be resuscitated due to a lack of modern facilities in their rural fishing village. Hence his determination to reconstruct the very traditional village in the image of Japanese modernity.

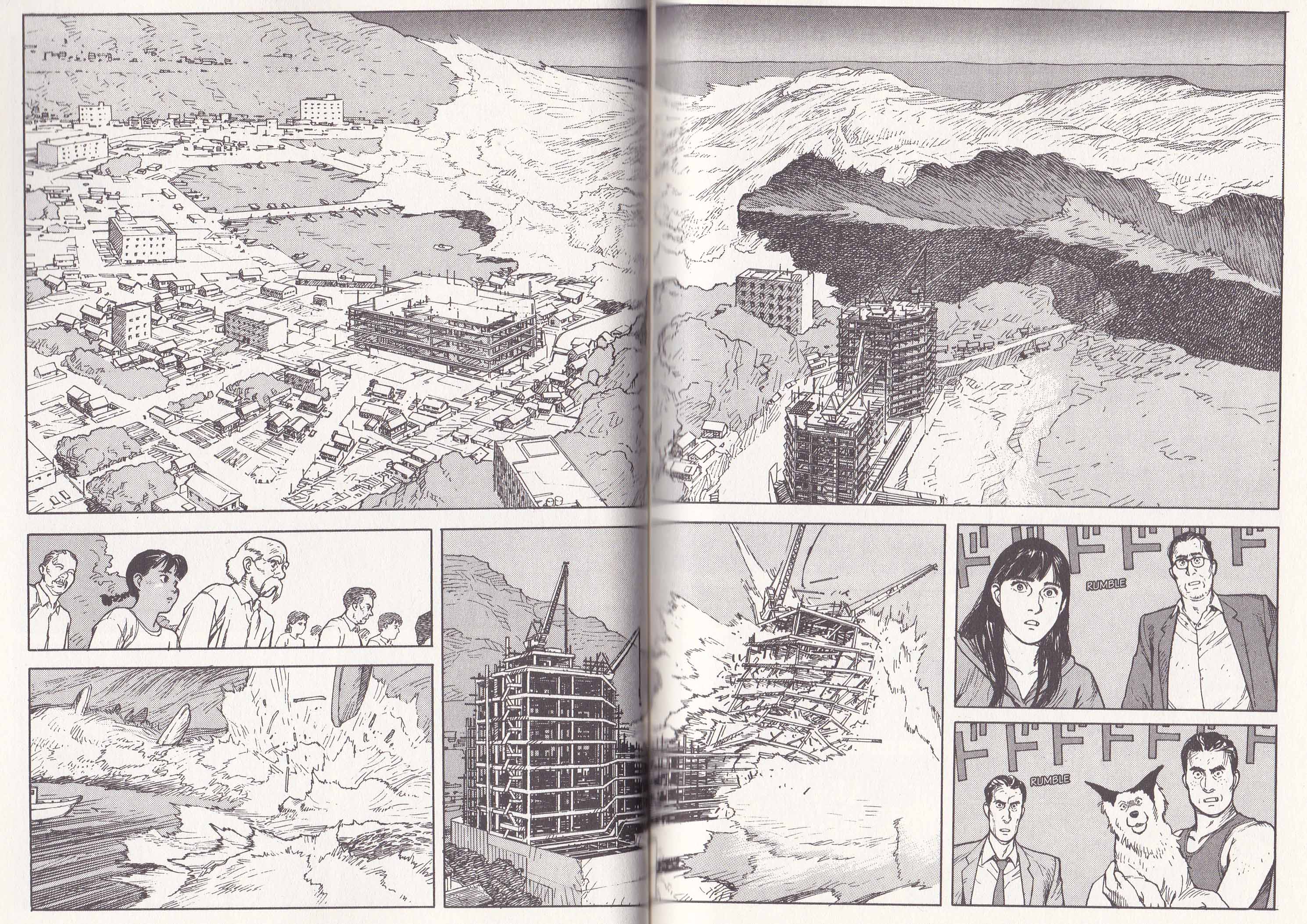

I did get the sneaking (but probably totally unjustified) feeling that the manga was chosen for translation and publication because of the current environmental tragedy afflicting Japan, the one resulting in the release of hundreds of tons of irradiated water into the Pacific on a daily basis. The representatives of the condo building and scientifically exploitative Ozaki conglomerate are dressed with all the finesse of the Yakuza elite. They want to turn the fishing village into a land of high rises and shopping centers and might as well be energy executives from TEPCO fiddling while the tuna get sick.

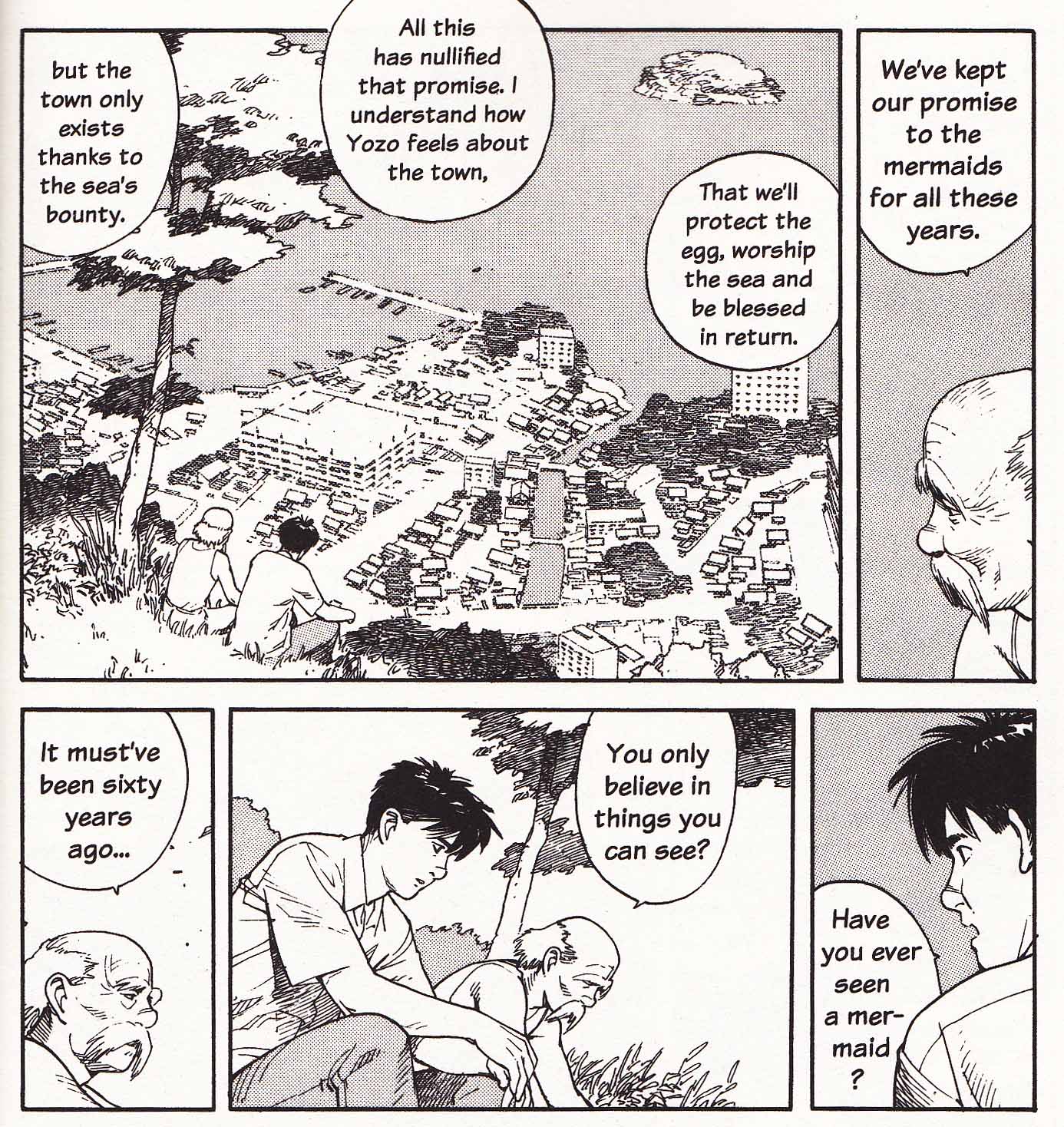

The last bastion of all that is traditional Japanese—hard working, salt of the earth, adherence to rites—is Yosuke’s grandfather. He rises from his sick bed to protect the pearl of great price—the mermaid’s egg which he has sworn to defend and incubate. One presumes that he belongs to the not so culpable generation; the young boys who had adulthood thrust upon them during the Second World War and whose only heritage (presumably) from that period is suffering—too youthful to have influenced that ignominious war which ended in defeat but just old enough to have built Japan up to its former (?) greatness.

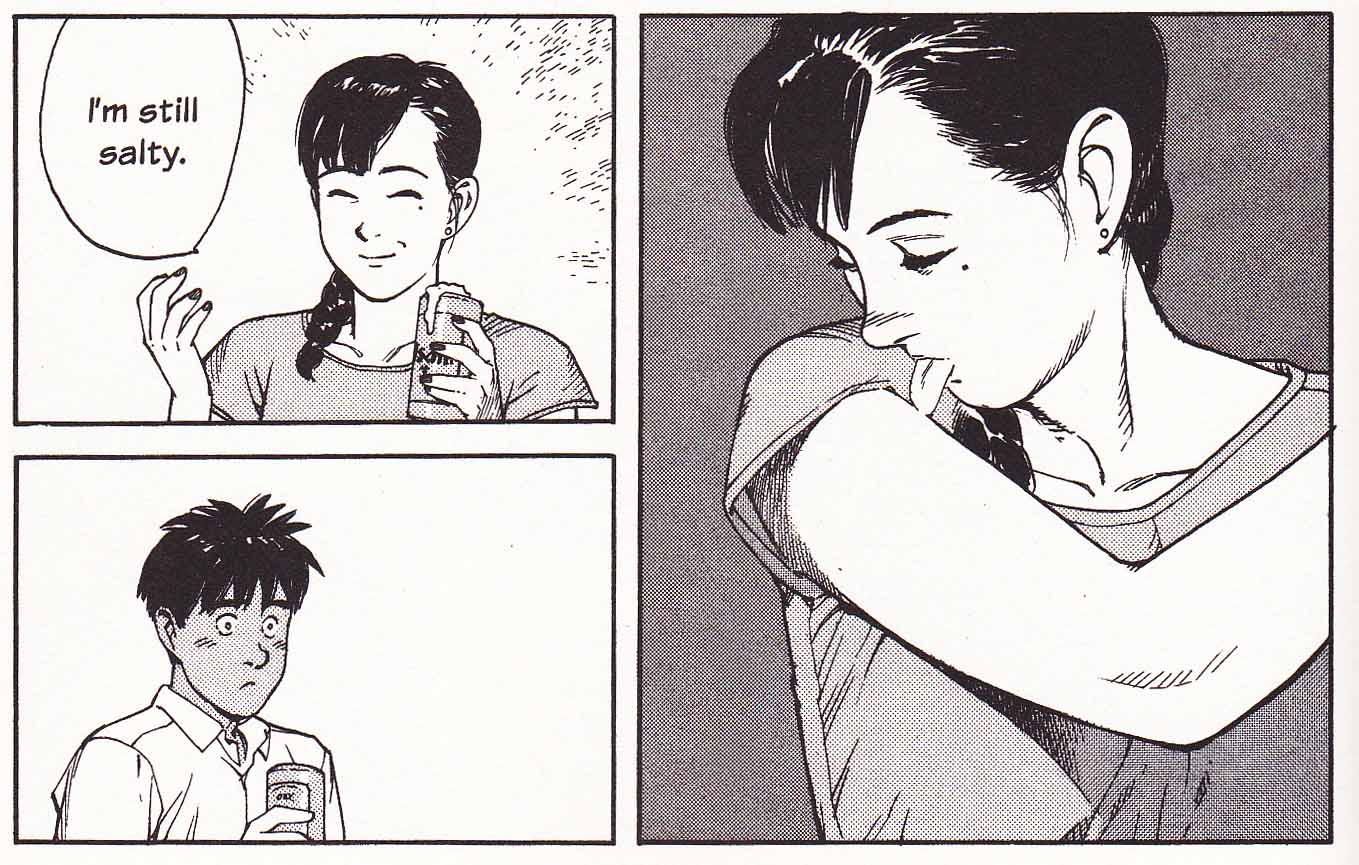

His misguided son is a member of that bubble generation of rank and file workers with little chance of career progression and hence motivation; still gripped by the siren call of lucre, eager to abandon the old for a faceless modernization. All hope how rests with the feckless yet capable young who have yet to be corrupted and remain potentially mouldable into some ideal of the Japanese spirit. Their rooms are strewn with idol magazines and other pop culture detritus but deep within remains a core of purity as yet unignited. They also have a not too shabby talent for swimming and are inclined to lick themselves like cats.

This glimpse of generational conflict is safe, conservative, and panders to the potential readership; at once portraying the friction between the young and their parents while extolling the virtuous wisdom of old age. It is also instructive as to Kon’s inclinations as seen in some of his early films—that railing against shallow and corrupt pop culture in Perfect Blue and that pining for simplicity and artistic purity as seen in the films of Ozu and Naruse (in Millennium Actress).

Needless to say, all of this is an illusion. An examination of the work of both these directors will belie the simplistic vision of generational strife seen in Tropic of the Sea. Nor are the seeds of Japan’s troubles (social or otherwise) quite as simplistically delineated as in the manga. There is nothing of the warmth and sadness of Setsuko Hara’s work in Late Spring or the complexity (some have said masochism) of Hideko Takamine’s performances in Floating Clouds and When a Woman Ascends the Stairs. Despite this, Kon’s nostalgia remains effective. For one thing, it would probably take some sort of artist ogre not to appreciate the artistry of women like Hara (Ozu’s muse) and Takamine (Naruse’s), the actresses paid homage to in Millennium Actress

In recent years, Western readers have been assailed by articles proclaiming the failing preeminence of the Japanese economy. Visitors to Japan will be very much surprised at these tales of the lost decade (or two), an experience which forms a part of the journalist Eamonn Fingleton’s argument in articles like, “The Myth of Japan’s Lost Decades.” Regardless of its truth, the narrative seems to have taken hold.

In Kon’s manga, this “failure” of modernity has led to a yearning for things past, one coupled with every form of blindness associated with nostalgia. This wistful craving for an earlier age and the guidance of the elderly is no longer tainted by sexism, the repression of the young, outright lies, or bare-faced cronyism. When a supernatural tsunami sweeps over the Ozaki developments, the President of said company resolves to continue with his plans but in a more sensitive and sustainable manner. This is Kon’s compromise and middle ground, the happy ending for all concerned. The Shinto-blessed Japanese walk hand in hand with nature into a brighter eco-friendly future; the pungent turd gilded into a constipated reminder that things past should not always be preserved.