The Comics Journal has an extensive piece up by Robert Steibel in which he looks at two pages of original art from Fantastic Four #61 and argues exhaustively, passionately, and convincingly that Jack Kirby was responsible for most of the ideas and plot. There’s a divisive and extended back and forth in comments as well.

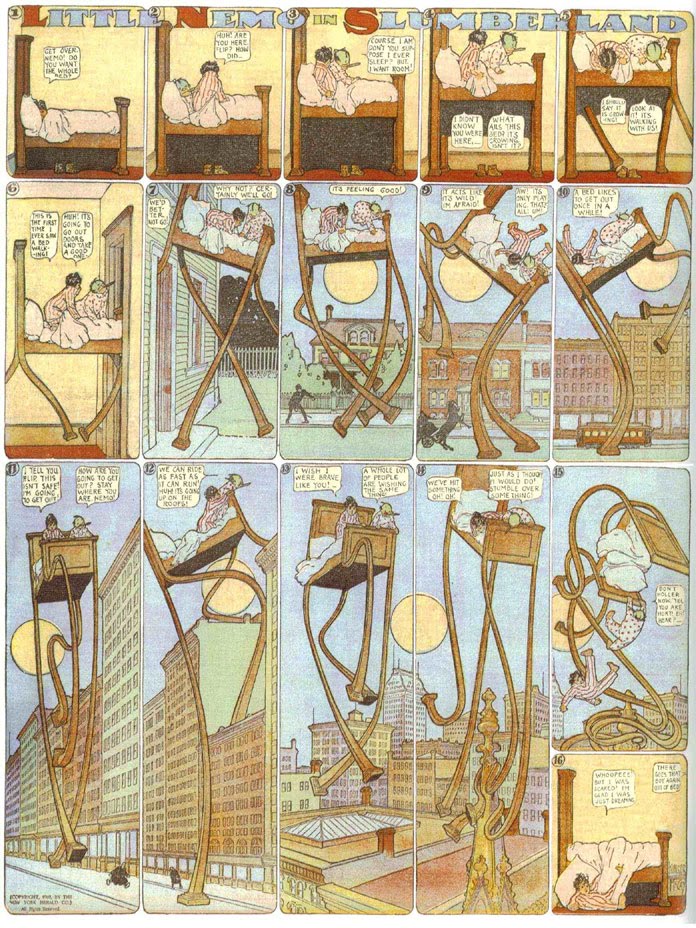

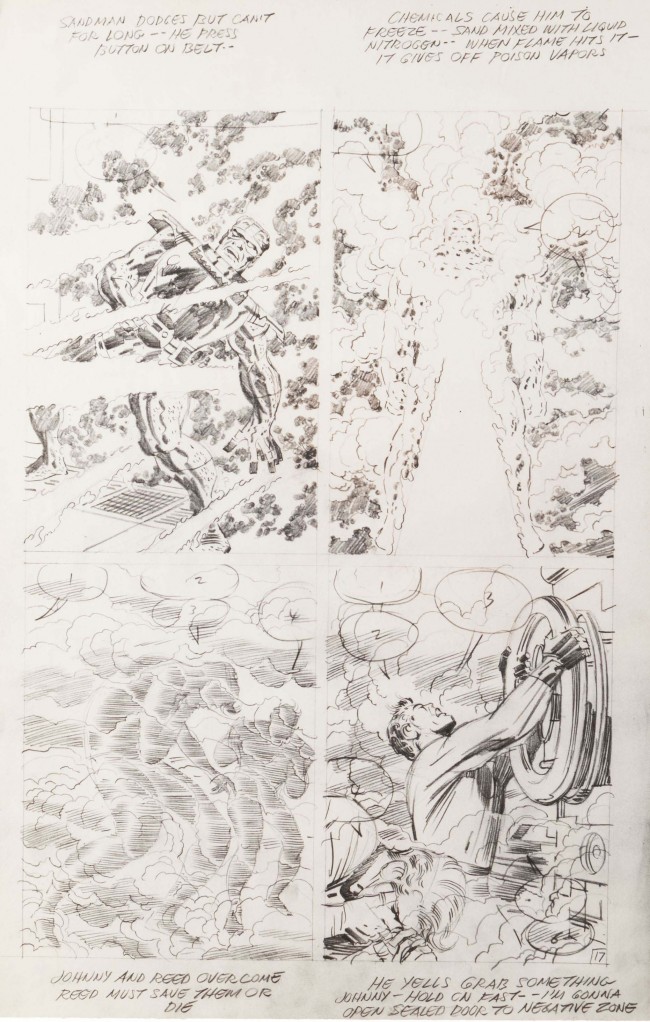

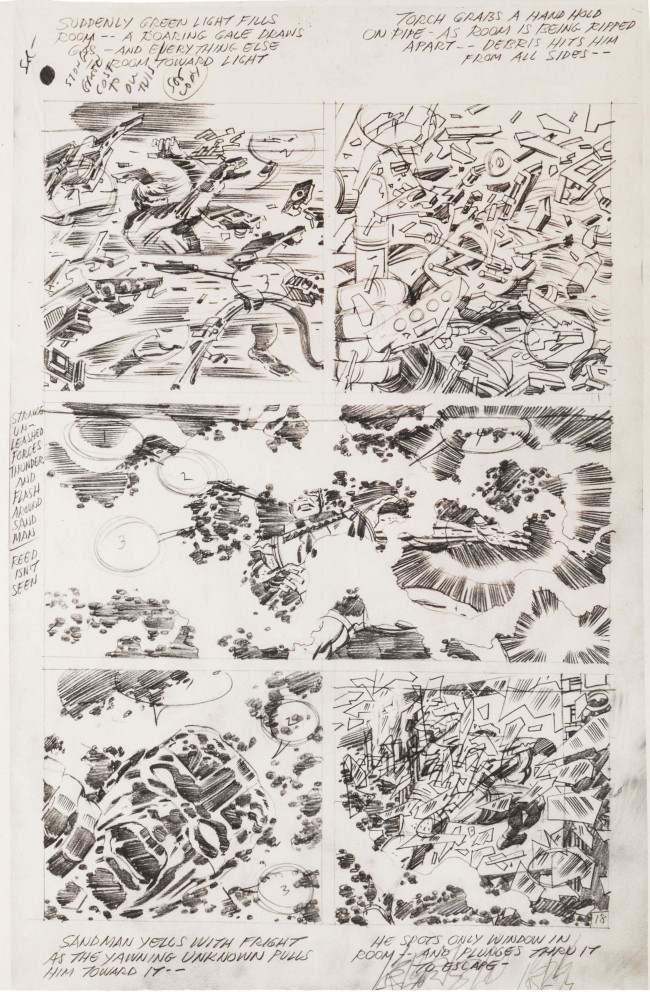

Here’s the two pages.

Those images are a lot of fun to look at; as with any art by Kirby, there’s a lot of energy, and it kind of only improves things that you can’t really figure out what’s going on in the draft form. Andrei Molotiu has talked about how Kirby can be viewed as an abstract artist, and I think that makes sense especially in these original pages. You can even see Kirby almost working to turn his characters into abstraction, with all the smoke and mist and debris and Kirby krackle covering everything, turning individuals into forms. Reed opening that negative zone is almost a way to breach the wall between form and nothing, with Kirby and everyone else rooting for the gloriously meaningless nothing.

And everyone is rooting for the nothing over the narrative because the narrative is incredibly stupid. Steibel talks about how “wonderfully creative” it is to have the Sandman freezing and turning into chemicals etc. etc. — but come on. It’s not “wonderfully creative” unless you’re standards for wonderfully creative are amazingly lax. I mean, just to stick with work for children, is the writing and plotting wonderfully creative by the standards of this?

Or this?

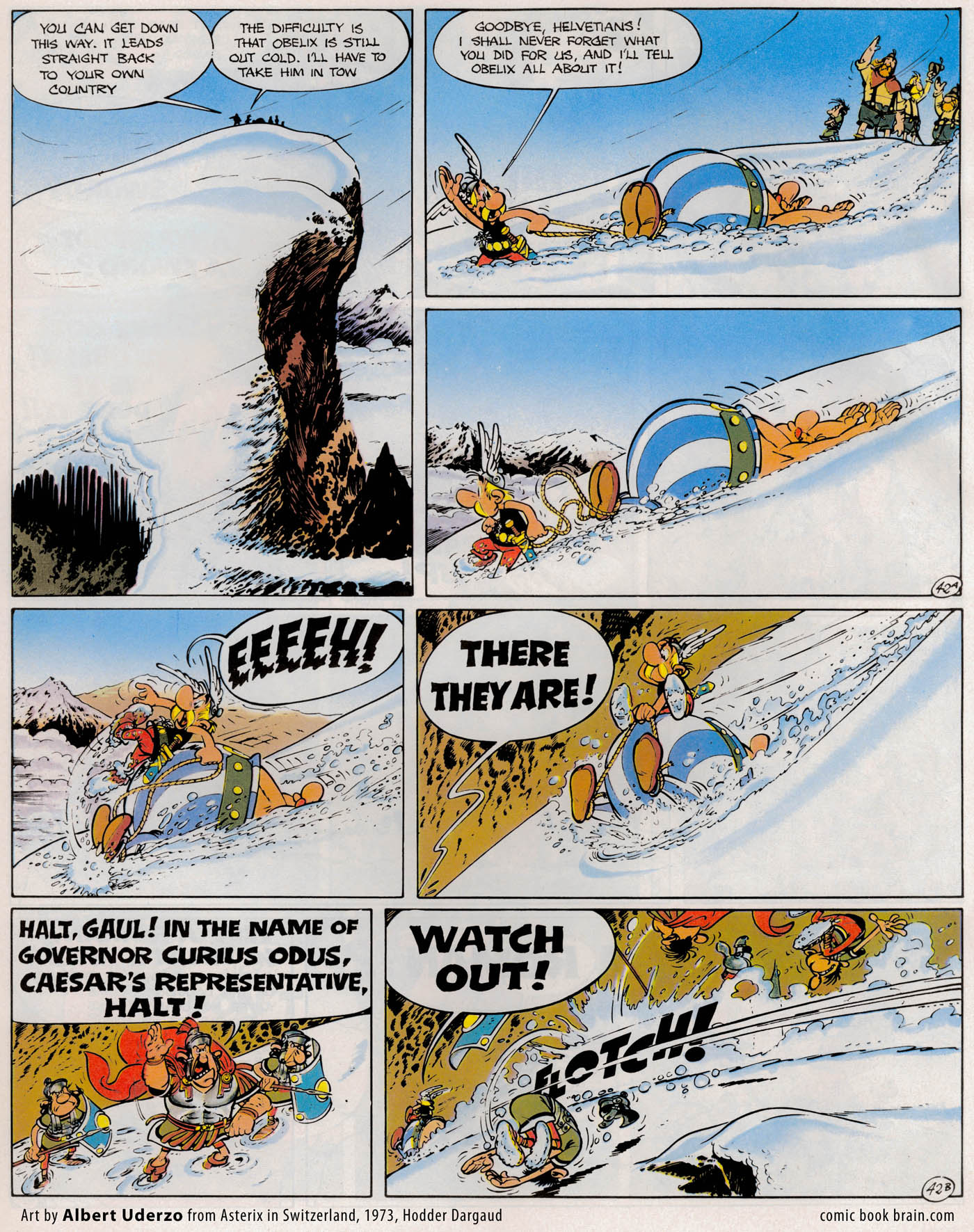

Or, if you want to compare fight sequences, with this?

All of those have wit and grace; the action mischievously escalates (in Nemo and Asterix) or ping pongs elegantly back and forth (in the Princess Bride). There are beats and timing built into the development, like that lovely moment where Asterix freezes and looks at something off panel before the crazed descent begins. There are winking hidden easter eggs, as when the tiny horse bucks in time to the giant bed in the Nemo page. There’s a use of visual action and dialogue to create characterization all through the Princess Bride. In comparison,the Kirby pages are just ponderous blaring; people screaming about how they’re trying really hard and are going to do something spectacular, over and over. There’s a super battle and yelling and things flying around, but there’s not any particular wit or style or even through line to the narrative. There’s just fight, setback, solution to setback, more chaos. It’s puerile, and mostly unreadable, even for two pages, even when you’re just looking at notes and don’t have to drag yourself through all the speech bubbles.

And yet, people are angrily, violently arguing over decades about who wrote this. Steibel thinks he’s doing Jack Kirby some sort of favor by declaring that the credit for the writing should virtually all go to Kirby. He even lists all the story elements/ideas to show that most of them belonged to Kirby — inadvertently demonstrating that the narrative is basically just a series of stuff happening without any real coherence or guiding vision. And, yes, okay, Steibel convinced me — Kirby is responsible for this incredibly stupid story as well as for the bizarre and interesting art.

Maybe, possibly, the reason that the Marvel method worked, the reason that the artist could make the story and Lee could just bubble it in, the reason that there’s so much uncertainty about who did what, is because the attention to story-telling and narrative was, on everybody’s part, incredibly half-assed. The only interesting thing in those comics is Kirby’s drawing, and they are most interesting, I am convinced, when you see them as formal exercises rather than as narrative.The death match over whether Lee wrote the thing or Kirby wrote the thing — it’s like arguing over who’s responsible for composing a spam email. It just always amazes me that anyone can manage to make themselves care.

People care because they imagine that if everybody just realized that Kirby wrote those stories, some part of the millions that Stan Lee has made, and continues to make, would be somehow magically reassigned to Kirby’s heirs. I think. Stan Lee’s millions aren’t for his writing or “creative” work, it seems to me — they’re for his very successful work as lovable shill for the company, without which Marvel would never have become what it has become. That shill role is justified by probably false claims of creatorship, granted, but exposing those claims doesn’t do a thing to help Kirby’s heirs.

That makes sense. Steibel actually argues the story is good though. Which just makes me shake my head.

I kind of like’em in the same way I like Axe Cop, and for the same reasons.

Great post, Noah. Short and devastating — in part because it its critical approach is about, you know, the art and the narrative.

Tellingly, the Journal shut down its thread about race, satire, and alternative comics after about 24 hours — without, I believe, any comments that one would characterize as unfair or particularly vicious — while they let the Kirby muddle go on and on.

To be fair, I think TCJ shut that down because they wanted to cut off someone spouting explicit white supremacy.

Joey, I see the Ax Cop comparison in theory…but I just like Ax Cop a hell of a lot more. The ideas are way weirder, there are more of them — and the story arcs are actually more coherent and interesting.

Having Jack Kirby illustrate Ax Cop would be pretty amazing though.

Creators rights and earnings aren’t anything to scoff at, money makes the world go ’round, but I resent that the Kirby-Lee debate is so central to comics discussion.

At the end of the day, Marvel’s ability to make millions on a character has little to do with the ‘genius’ of the superhero concept, but everything to do with the marketing-licensing machine of Marvel. I’m not sure if this machine favors truly great characters (or supports competent storytelling.) I think it favors characters that are deeply licensable. Not to say that Kirby doesn’t deserve adequate royalties from the absurdity of having these characters on shirts and movies and whatever, over and over again. Just that the discussion of it is petty and depressing– whatever ‘art’ Kirby created in the name of Fantastic Four really hasn’t made it two passes through Marvel’s capitalistic filter, to have anything to do with why these characters are so enduringly popular now.

It is hard to figure out what the relationship is between the original creation and the marketing juggernaut. I do think there’s something there — Kirby created a lot of recognizable, visually dynamic, interesting characters, and that has something to do with why they’re so popular over time. But on the other hand it’s hard to argue that there was much of anything worthwhile in the original Batman comics, which are much worse written even than the examples here and have hardly any visual interest at all.

How about wonderfully creative as compared to the rest of 60’s children comics? Because I think that is what he is saying. He is not comparing it to Pynchon.Also some of us are just interested in reverse engineering these stories.It appears you are not.

I”m not comparing it to Pynchon. I”m comparing it to Little Nemo and Asterix and the Princess Bride, all aimed at even younger kids than Lee and Kirby, I’d guess. If you think that’s unfair, I don’t know what to tell you.

I’m somewhat interested in the reverse engineering. The hagiography that goes along with it depresses me, though.

Like I said I think he is comparing it to other 60’s mainstream comics. The hagiography and backlash is tiresome. We are a society of outrage and arguments.

“The death match over whether Lee wrote the thing or Kirby wrote the thing — it’s like arguing over who’s responsible for composing a spam email. It just always amazes me that anyone can manage to make themselves care.”

If you’re following the @Horse_ebooks/Buzzfeed scandal, you know that some people care very much who is responsible for composing spam.

Matt, I’m not following that, I’ll admit. Care to summarize?

George, I don’t think I sound particularly outraged; just exasperated.

Steibel says that the writing is “wonderfully creative.” I don’t quite know how to read that except that he thinks it’s wonderfully creative. And you appear to be saying that 60s comics is a particularly debased artform that is too crappy to even be compared to other children’s comics. Is that your intention?

For me the debate only gets really unbearable when people start comparing them to Lennon and McCartney.

I also wonder why there are people who seem to be a Kirby-Was-An-Asshole Party and resent the notion that he was cheated, financially or otherwise.

I think George seriously underestimates Steibel’s enthusiasm for the material. I don’t think Steibel considers Kirby’s FF work only good/great for the 60s. More like the entire history (and spectrum) of comics.

” I’m comparing it to Little Nemo and Asterix and the Princess Bride, all aimed at even younger kids than Lee and Kirby, I’d guess. If you think that’s unfair, I don’t know what to tell you. ”

Maybe that’s a category mistake though. Marvel superhero stuff isn’t aimed at children, it’s aimed at pubescents, most of whom would find Little Nemo and Asterix boring. I think adults find it easier to appreciate childen’s stories because the mindset is far enough removed, whereas the adolescent mindset is too close and feels embarrassing. Just a thought.

Hmm. That’s interesting about adolescents, I guess. What good examples of adolescent literature are there, then? I think Lee and Kirby is pretty crappy writing compared to, say, the manga Parasyte, or to the Moore/Bissette Swamp Thing, or the Miller Dark Knight, which are all aimed at adolescents, I’d imagine. Rotten compared to Say Anything, which is aimed at adolescent audiences. It’s fairly dreadful compared to Ender’s Game. I guess it’s arguably comparable to Star Wars, in that the writing/narrative is crap but the visuals are great. I don’t know; what would you compare the writing to where it would rank as “wonderfully creative”?

Noah, I didn’t mean to imply that you were personally outraged, just that the K/L gets heated. I come from a jazz music background and that is my “reality tunnel”. Jazz, like comics has been going on for so long that musician’s don’t compare creativity over the past century, more like in the decade discussed. I wouldn’t compare Art Blakey with Vinnie Colaiuta, more with Art Taylor. The music is a part of time and space.

FuFu, I think this is a good point. However, superheroes are kind of weird because I think they are simultaneously aimed at children and at pubescents. There are other properties, like Harry Potter and Nickelodeon’s Avatar, that fit this bill too, but with different results.

Noah, yeah, that was a little harsh of me, as Kirby’s draftmanship definitely laid a foundation for Marvel to build upon. And Fantastic Four are not as ‘sticky’ as many of the other Marvel/DC creations, marketing-wise. But the Batman point is a perfect example of what I’m saying.

Sometimes I better understand the royalties and attribution scandals when I think about it in term of ‘damages.’ Kirby deserves x amount of recompensation for the damage that Marvel has done to his characters in their ruthless licensing, etc. Because otherwise, making mainstream comics is reduced to an exercise in branding. I have no love for them, so I’m OK with seeing them that way. But then mainstream comics seems like a poisonous nexus in the comics web that can’t be ignored, that comics have to engage, or will end up engaging anyway.

FuFu makes a good point. I used to do childrens’ theatre, and occasionally a class full of teens would get trucked in, and they always HATED it. We’d go interact with the audience, in character, you know, and kids usually liked it if they weren’t too scared, but teens were always too cool for that baby stuff.

Maybe Superheroes of the 60s broadened the audience by bringing older readers into the fold, but now it seems like their’s not much clarity about how to please both audiences at the same time.

George, this seems like a common position, but it just seems bizarre to me. Neither comics nor jazz are very old as art forms go. I don’t see anything wrong with comparing Harry Potter to C.S. Lewis or Roald Dahl, for example — or to Alice in Wonderland, for that matter. Similarly, talking about why I like Louis Armstrong more than John Coltrane seems like it would be a completely reasonable thing to do. Context matters, certainly, but the resistance to comparing artists just leaves comics isolated and insulated; it makes it irrelevant to anyone who isn’t already invested in it, it seems like to me.

I totally agree with you that those comics are silly. It is unfortunate that in an attempt to get some satisfaction, the Kirby family must clarify Jack’s responsibility for the entirety of the wretched Marvel machine, they who produce horrendous comics and are now also busily destroying the narrative standards of the film industry. At least as far as I am concerned, the issue at hand is really all about the Kirby family getting some part of the huge amount of monies that have been generated by Kirby’s creations. I don’t begrudge Lee what he gets, I resent that he felt the need to get it by digging his boots into the backs of his collaborators. He didn’t HAVE TO testify that he was the sole creator of these properties when the fact is that he wasn’t. He CHOSE to do that. Kirby was the author of those comics in every way that counts; Lee’s part was to glaze them over with a veneer of copywriting and construct a PR identity for the company. They both deserved some reward for their successes, but Lee ensured that it was only he that got any. This is the real reason for the ongoing controversy. That Kirby’s solo work produced a handful of works of real value is another matter entirely.

Fair enough, James. You actually seem to be on something of the same page as Kailyn, re: the frustration with the way that the business arguments have swamped consideration of the merits of the art, in various ways.

@Horse_ebooks is, or was, a spam Twitter account that gained a lot of hipster cache for the accidental poetry it generated while rather ineptly trying to sell ebooks. Unbeknownst to anyone until recently, someone from Buzzfeed bought the account a couple years ago. Since then, what its fans celebrated as unintentional bits of absurdist poetry created by a bot have actually been part of or promotion for some sort of conceptual art, intentionally created by this guy at Buzzfeed. The curtain was thrown back near the end of last month, and now everyone is mad/disillusioned.

More comic book fans ought to read Barthes.

The discussion in this thread about literature for children vs adolescents and whom these comics were aimed at reminds me of something I read from Jim Steranko a while back about how he approached his SHIELD comics. He said his comics had three different audiences. There were younger kids that couldn’t or wouldn’t read, who just looked at the pictures. There were slightly older kids that took the adventure stories at face value. Then there were adolescents and adults that read it as camp. His aim was to please all three.

Matt H— Please expand further on Barthes. I have read a bit of him

Ha. It was a flippant comment–I’ve probably read less than you. But wouldn’t his view be that the Lee/Kirby comics were authored by neither man but instead an accident of history?

Or am I getting Barthes confused with someone else? (I am entirely uneducated. All I really read is comics and arguments on the internet.)

I’ve said it many times before but I think Kirby and many artists of his era would best be done justice by art books that selected his best covers, pages, panels and sketches with notes about his better ideas (I think some of the ideas were cool, like that big collective brain in The Eternals) so I dont think his accomplishments were solely visual.

Noah says in this article: “Steibel talks about how “wonderfully creative” it is to have the Sandman freezing and turning into chemicals etc. etc. — but come on. It’s not “wonderfully creative” unless you’re standards for wonderfully creative are amazingly lax.”

Noah says in Hulk/Koons article: “There couldn’t be a much more devastating demonstration of the justness of that high-low hierarchy”

I’ve tried to resist commenting on these articles because I dont think I can justify the time I spend writing my comments, but the parts I quoted killed my resistance.

I think “devastating” is grostesquely exaggerated praise even worse than Steibel’s and I feel a bit disappointed that you would go that far over the top. I think calling the Koons piece “faintly amusing” would be generous but more appropriate. I think the bronze/plastic inflatable Hulk is most impressive in what they done with the materials. The idea that the piece is some blow to Hulk and his fans is utterly baffling because if your interpretation was taken as the Koons intentional one, it isnt remotely witty or stinging.

I doubt Koons meant it to be an insult because I’ve heard him talk about his grand theme being about getting rid of guilty pleasure and being honest about the things we like, however seemingly low or trashy. When he talks like this, I like listening to him talk more than looking at his work. I also like listening to Duchamp talk more than looking at his most celebrated work. You could say I find him an interesting philospher but a mostly boring visual creator.

Some might say it is tragic how many artists are more interesting to talk to/listen to than to look at their work.

I kind of wanted to like these artists, but that uncomfortable Robert Hughes tv interview with Koons also made me think there was nothing much to see.

I dont like much pop art and conceptual art and find most of it depressingly dull but I am very interested in listening to what the artists and their fans have to say in case their passion and understanding might rub off on me. Yoshitaka Amano liking Koons was encouraging.

But when I listen it mostly goes toward confirming the things I didnt like. However much intellectual acrobatics there are behind the pieces, if the piece itself isnt visually stimulating, (even a very slight quick sketch is more satisfying to me than a mountain of ideas without stimulating visuals) the idea somehow seems flimsy and pathetic. It would have been more impressive to me as an idea on paper; maybe I think the artists seem silly for going to all that trouble when the idea is better on paper.

Extensive explanations for imagery generally tend to put me off with occasional exceptions(I’m curious about reading Sontag’s Against Interpretation). I often feel as if the explainer is ashamed to admit to enjoying simple things, as if the greater length of what you can write about something reflects the power of the piece. Like those tiresome music journalists who go on endlessly about lyrics as if that were the real meat of music; who probably dont listen to instrumental music. I tend to find the biggest music fans see good lyrics as a nice but unnecessary bonus, but some music traditions do place lyrics high above the sounds and I guess there is nothing wrong with that if they really enjoy it that way.

I recently wanted to draw images of masturbating men, but then I had to think about the way I did it because I was worried viewers would think this was some negative mocking satirical comment on something, when I’d hope the viewer would just see the pleasure of masturbation. I dont have anything against satire as a whole but I do find a lot of it banal and predictable.

I used to have some faith that the art I liked best was marginalised for a good reason. But these days I have almost no confidence left in people who insist an image should be morally and intellectually improving. So I feel Ernst Fuchs, Remedios Varo, Albin Brunovsky, Nicholas Kalmakoff, Robert Venosa, Andrzej Masianis, Allison Schulnik etc have not been raised nearly high enough because they didnt have anything obviously “relevant” to say, but music can easier get away with that.

As much as I love cultural creations, I seldom have use for a word like “devastating” unless I’m describing the trauma of disappointment with books, films and comics and some extent music and drawing/painting/sculpture/photography.

I’m going off topic quite a bit and probably should have commented on the earlier pieces but I’m not sure I’ve told you my Hulk story, you might be amused by it…

In my late teens for the time wasting sake of it, I was rewatching 90s Marvel cartoons I had on VHS tapes. To my astonishment, every time I watched the 90s Hulk cartoon intro, it made me cry. It sounds unbelievable and it is one of the most bizarre and difficult to explain reactions I’ve ever had to anything.

The cartoon itself wasnt any good, I’ve not read a whole lot of Hulk comics and although I liked him, he was never a favorite; but I feel like that 90s Hulk cartoon intro summed up most of what I liked about Hulk and his story.

I think the Hulk almost seems to me like an accidentally potent character. The earliest Hulk comics are pretty tedious (the Kirby issues had some interesting stuff but the anthology stories after the original miniseries were abysmal) and the anger theme was not there from the very start and I think it taken quite some time for it to be really explored. ((Barry Windsor Smith accused Bill Mantlo of stealing his ideas about the father/child abuse anger element. He also said that Mantlo had a reputation for plagarism of other writers. So it has been interesting to see the recent appreciation of Mantlo because he written some of the worst comics I’ve ever read with horrendous dialogue, so it is nice to hear that there is far more to him than what I had previously known of him.))

From watching that intro, it almost still gives me a longing to see a definitive Hulk story that might already exist but probably doesnt and I dont have it in me to look for such a thing. I’ve toyed with reading the whole Bruce Jones run because at his best, Jones is my favorite comics writer ((I read the first few issues and they were good, some people said it was one of the best thing Marvel ever put out in recent decades)) but I’d rather check out his novels.

That longing feeling that the best ever story of a decades old superhero comic has yet to come and could be right around the corner is an impulse I understand but I think it should be resisted because I feel it creates endless piles of bad comics, for reasons I cant be bothered going into.

I’ve felt that about Fist Of The Northstar because every version has some serious flaws and I’d love there to be one version of it that did everything perfectly. But I think people should just move on and create something new, perhaps taking elements from the old stories you liked; in my dream fascist regime, I’d outlaw new installments of stories that arent guided/participated by the original creator(s). No more adaptations either. Some of my favorite films and comics are adaptations and I would miss cover songs a little but I think things would be better without them. If that became a reality, classical music and theatre would be totally different, Bach, Wagner and Shakespeare on screen, audio and pages only; no new performances, let the new kids in.

What I liked about that 90s Hulk cartoon intro: It gets that aspect of an intellectual having his life continually, seemingly endlessly ruined by another uncontrollable idiot version of himself. Most people get angry, stressed or scared do something stupid and the consequences of their actions sober them. Bruce Banner doesnt have that. Anger can make you feel invincible for a very short time, but you usually feel hopeless after the consequences of the anger. But Hulk gets stronger with anger and he really is just about invincible. You can get angry and punch a wall and hurt your hand, feeling stupid and pathetic, but Hulk can smash as many walls as he wants. Hulk rarely has any horrified realisation of what he has done, the destruction goes on and on and on until he is lucky enough to find some quiet place or someone soothing to calm him down (there are plenty of exceptions where he is trapped or something, but I’ll not get into all the times he can be temporarily stopped).

I find the idea of him being unstoppable and able to destroy almost anything he wants both exhilirating and and really sad. I think the idea of the childish Hulk wanting peace by himself really cute and sad.

I also like that Hulk thinks of Banner as a totally different person. I find it interesting that it has that Jekyll and Hyde aspect yet Banner never does anything wrong, the grief he faces in the aftermath of Hulk has little to do with his actions, he doesnt really have a darker side that causes all this shit.

I’m not describing this nearly as well as I thought I would, I probably dont fully undestand why that intro made me cry. I’ve never got into serious trouble from anger, I’m not violent, although I do have OCD paranoia that I could do something violent in the spur of a overheated moment but it never happens. I think I just hate being angry, it feels horrible. I dislike that aggression is so widely accepted and unchallenged and I regret that there is probably some agression in this post that I’d like to remove but I cant take forever writing this, it has already taken far longer than I planned. Probably lots of crappy generalisations too.

I hope all this makes sense.

Barthes and Foucault both have death of the author arguments. I’m more familiar with Foucault’s; he argues that the “author” is basically a nexus of power/authority. He generally sees indiviuals as secondary to discourses — so not that a text is an accident of history so much that it’s created by various discourses (in this case, adventure narratives, science anxieties, American individualism run amok) rather than by people per se.

It’s kind of an extension of the Freudian/Marxist view of texts as symptoms.

Have you read more than two pages of this comic?

Nope. I’ve read lots of Kirby, though. And Seibel is saying that these two pages are well written. They don’t seem to be.

Are you claiming that in context they are? If so, how come?

If I’m not mistaken, Foucault actually notes that authors are created out of the discourse of copyright and copyright infringement. That is, there is no need for an “author” to exist, until the question of who “owns” the material and who gets paid comes into play. Once that happens, “anonymous” authorship becomes much more scarce and “authors” are “created.” Authors don’t create discourses; discourses (in this case, the discourses of ownership and copyright) create authors. Which is basically what the Lee/Kirby debate is about in the first place. Foucault says other stuff too…but this seems the most relevant to this discussion. (“What Is An Author”–Barthes’ is “The Death of the Author.”

I haven’t read it in a long time, but I remember loving that issue (or the reprint of it I had, at least) when I was about 11 or 12.

I would say to a 12-year old that loves comics the whole liquid nitrogen/poison gas thing _IS_ wonderfully creative – as is blowing open the hatch to the Negative Zone – the latter esp. in the way that these comics (as much as I disdain continuity these days) made use of elements introduced in previous stories creating a sense of a rich tapestry of bizarre over-the-top physical universe and the pseudo-science that went along with it.

Even now looking at those panels, I still think they are really creative and fun, and it is only Lee’s overly-obvious turgid dialog that stinks.

Some might say that Lee’s overblown campy dialogue makes the entire enterprise more acceptable – at least, he knew what Kirby was peddling and ratcheted it up. Kirby’s scripts tend to give the impression that he was taking everything rather seriously. Especially in The New Gods books. I prefer the more silly Demon stuff.

“Some” might say? Would you say?

Overblown is fine. Over-obvious, in the sense that it basically explains what is depicted, is what I find detracts from the sequence of panels.

I sort of agree with Suat– the more serious the comic takes itself, the less seriously I can take it… funny how that works. Yet I’m not sure how much Lee’s overtly campy dialogue helps make the comic better– it seems snide.

Osvaldo, I’m really glad you post here at HU, because it’s great to have a champion for these comics. I hope that’s not weird to say…

Maybe overblown isn’t just fine, but very preferable for all audiences involved. People who want to read the comic seriously don’t feel laughed at, and people who want to read the comic as camp get to feel like they’re ‘watching’ the authentic thing. That the comic isn’t looking back at them. That they’ve caught it in the act, as if the enjoyment of camp is a breed of voyeurism. Am I paraphrasing Mulvey or Greenberg or someone?

I don’t know if I’m a “champion” for these comics. I just look for a place to engage with them somewhere between uncritical fanboyish nostalgia and total dismissal as a dungheap.

I kind of come at this stuff from an angle influenced by cultural studies, in which I am more interested in how readers and writers engage with these texts and put them to work in various ways than in flogging the structure of their narratives or belittling the joy of playing at being serious – which some of these comics do. I like to feel like I am playing with them, too in my own way by writing about them and that makes them valuable.

Just to reiterate, I don’t think the comics are worthless. I like Kirby’s art. I just don’t have a whole lot of enthusiasm for the narrative.

The thing about cultural studies is, if you get rid of aesthetic evaluation, you kind of raise the question, well, why write about this rather than something else? I guess with these you end up with historical importance or as you say, nostalgia. Both of those are really backward looking though, so it becomes hard to make comics a relevant conversation outside of comics (except insofar as nostalgia is itself marketable…and in fact, comics often function as a market of nostalgia in lit fic or journalism, or in comics themselves.)

Sure. You are right that nostalgia can operate that way – a kind of rabbit hole of pleasing reflection on the past, but I would argue that when best used (or reflected upon), comics are a lens for what Sinead McDermott calls “critical nostalgia” as a mode of engagement with the past that “functions as a means of defiance against attempts to erase or deny the past, as well as rendering visible the links between individual and collective memory” (404). It “can serve as a mode of critique, highlighting the disjunctures and differences between past and present and refusing attempts to impose a seamless narrative” (405) and “allows the past to be retrieved differently: not as a single line leading from then to now but instead as a cluster of memories, desires, and possibilities that do not always lead in the direction of the present” (405).

Why write about “this” as opposed to “something else”? I think “Well, I like this” (or “I don’t like this”) is good a reason as any to spend time with it. I mostly stand with Bordieu on aesthetics.

Right; I don’t like it or I do like it works fine, but still — why is this the thing you like? The answer, “I liked this as a kid,” is fine too…but I don’t know that that’s always a means of defiance. Nostalgia for this particular thing, for example, is really reified and even institutionalized. The narrative of nostalgia for comics, and Kirby in particular, is actually a kind of cliched part of narratives of male adolescent development, either in rejecting it or embracing it.

Not that you can’t tell different stories with that nostalgia, I guess — but there’s a lot of baggage there. If you want to be critical about the way the nostalgia is working, I think you’ve got to engage the way that nostalgia in this instance is quite, quite normative.

“And yet, people are angrily, violently arguing over decades about who wrote this.”

Actually, this is not true. There is no argument, although Steibel and so forth have convinced themselves that there is. Lee has acknowledged Steibel’s basic points about his and Kirby’s relative contributions to these stories since they were being published.

All Steibel and similar Kirby idolaters are really interested in is trashing Stan Lee, who they somehow see as thwarting Kirby’s apotheosis. They cannot discuss anything without turning the conversation into another round of Lee-bashing. In order to justify this, they pretend there is some massive campaign against their idol. From my own experience, it seems they’re at best grossly overreacting to statements that don’t completely confirm them in what they say and do.

Frankly, I’d like to see the names of the alleged Lee supporters who have argued that Lee was the prime mover with regard to the individual Marvel stories, such as the one Steibel discusses in his article. I also want to see these names along with links to where they have made these alleged arguments. Show me some proof that Kirby idolaters such as Steibel are fighting an enemy that actually exists.

Noah — I’m not going to get into the whole “that FF story sucks compared to this or that,” but I will say that citing Asterix as an example of non-silly creativity is a bit curious. For, while it’s a fun strip that works, at its core it’s basically a comic strip about the adventures of lovable, happy-go-lucky barbarians, loosely modeled after Abbott and Costello — barbarians who get super strength from magical potions. As someone who has read Julius Caesar’s “The Gallic Wars,” I don’t find Asterix’s exploits to be any less silly than the storyline in “Fantastic Four” #61.

In any case, here’s what I posted a few minutes ago on the TCJ thread prompting your essay:

“At the time FF #61 was published, Kirby had already been doing the lion’s share of creating and plotting of the series for years. I don’t think any objective observer can deny that.

Lee’s forte was never world-building or other such innovations, nor was it outside-the-box plotting. He also had difficulty creating new characters or villains that were not simply carbon copies of generic characters he had seen or created previously. This is pretty obvious if one looks at Lee’s career as a whole. The only time he was involved with a seemingly endless stream of new ideas and original characters was the relatively short period of time he was both utilizing the Marvel Method and working with Steve Ditko and Jack Kirby. And the reason for that is simple: Lee did not do any of the creative heavy lifting — Ditko and Kirby did. While I never spoke to Kirby, Ditko explained to me that Lee never put much thought into what was coming up. He might suggest some random existing villain during a plot discussion, and Ditko would have to talk him out of it. Ditko was driving the creative train on Spider-Man and Doctor Strange, as no doubt Kirby was with his books, and to his credit, Lee was smart enough to let them do it.

But while both Ditko and Kirby were geniuses as creating new characters, villains, dramatic situations, and riveting storylines, both had trouble writing smooth, relatable, emotional, humorous and enjoyable dialogue. Lee could. In addition, neither Ditko or Kirby seemed comfortable at the art of self-promotion, whereas Lee exceled at it. Lee was also an excellent editor, and seemed to know how to get the best work out of his staff. He had a knack for sensing when some art or concept he was presented with would or would not work.

So while Lee’s dialogue often ‘stated the obvious’ or closely followed the directions of his two top artists, the fact is, Lee’s dialogue was critical to smoothing out the rough edges and jerkiness of the artists’ margin notes.

In short, while Kirby and Ditko created the majority of the Marvel Universe during the 1960s, Lee was the guiding hand, glue and the catalyst that made the whole thing work. None of the principles involved enjoyed anywhere near the same success working separately than they did working together. Like the Beatles, they had a special synergy whose whole was far greater than the sum of the individual parts.”

Yes. I think we may be arguing the same thing. Nostalgia is TOTALLY normative and very dangerous, thus the importance of engaging with _critical nostalgia_.

Robert, I think there is a wider cultural recognition of Lee outside of comics circles. I’m sure anyone who knows anything about it knows that Kirby is the one who did most of the creative work, but most people who think about Marvel/Lee don’t know/don’t care. I’d imagine that’s the source of some of the frustration; the facts are quite clear, but there isn’t really anyway to convince people who kind of by definition aren’t paying attention.

And then, as I was posting that, Russ posted defending Lee’s contribution! Though really I don’t know that Russ’ position and yours (or Seibel’s) are mutually exclusive.

Russ, I wasn’t arguing against Kirby for being silly. Almost the opposite; I like whimsy. My point was that the plot/narrative on that Asterix page is modulated and clever and rewarding — there are beats and expectations raised and reversed, and so on. The Kirby is just loud and clumsy, IMO. (Though more visually daring and inventive — not to denigrate the art in Asterix, which I like too.)

Osvaldo, that’s fair enough.

Though…now I’m curious to know if there’s any comics criticism that makes the case for 50/50 in credit, or something like that. Suat? Are you reading? (Maybe I’ll email him.)

If there’s a wider public recognition of Lee, I think it’s because he does a lot of press and publicity work for Marvel.

The company’s position appears to be that Lee is the co-creator of the various features. As can be seen from the recent Fantastic Four and Spider-Man movies, if Lee is credited as a creator in the main titles, Kirby or Ditko are, too.

Independent reference works and histories that deal with Marvel, from the Wikipedia pages to Mark Evanier and Sean Howe’s books, all make a point of describing the issues surrounding the credit questions.

I agree that public apathy and ignorance is probably at the heart of the Kirby idolaters’ frustration. But they can’t seem to accept that anyone interested in finding out more about Lee, Kirby, and so on is going to learn about this topic very quickly.

Russ wrote:

The only time he [Lee] was involved with a seemingly endless stream of new ideas and original characters was the relatively short period of time he was both utilizing the Marvel Method and working with Steve Ditko and Jack Kirby. And the reason for that is simple: Lee did not do any of the creative heavy lifting — Ditko and Kirby did.

I agree with that. So do Steibel and the rest of his particular breed of Kirby idolaters. As far as I can tell there is no dispute about this, but Steibel and so forth insist that there is.

I daresay they would point to Russ also writing that “Lee was the guiding hand, glue and the catalyst that made the whole thing work” as proof that he’s among the enemy they’re fighting against. Honestly, from what I’ve seen, they would treat that latter statement as the sum total of everything Russ wrote in that comment, and probably everything else he might write in this thread as well. Unless, of course, he wrote something they would consider even more objectionable, and then they would focus on that to the exclusion of all else.

Well…I don’t necessarily want to refight the thread over here. And I’m sure everybody can sometimes be ungenerous in the heat of argument. Maybe we all can just agree to disagree, or agree to agree, or some variation thereof.

If I had to put a number on the percentages of Lee’s and Kirby’s contributions circa 1965-1966, I’d guess-timate Lee at 10 percent and Kirby at 90 percent — which is actually close to Steibel’s assessment. But even though Kirby did the lion’s share of the creating, Lee’s 10 percent was pretty important.

Some Kirby fans may disagree, but the fact is, when Kirby jumped ship to DC and wrote his Fourth World books, I went from eager anticipation of what was coming, to abject disappointment, after reading just a few issues of books featuring Kirby-only dialogue.

I asked before, but I think it got lost in the bustle — did Kirby ever work with a scripter other than Lee post-60s? And is what do people think of Simon’s writing? I don’t know that I ever read any of those….

Noah–

I understand where you’re coming from, and I’ve actually resolved not to get into it with these guys any further. I removed the inflammatory remark at the end of that comment.

I agree with Russ about 90/10 being the proper split of credit. I also agree that Lee’s 10 wasn’t extraneous. Their contributions were both necessary to make the material work the way it did.

After the ’60s, Kirby would not work with a scripter unless he was provided with a full script, as was the case with that Silver Surfer book he did with Lee for Simon & Schuster. DC and Marvel both went along with him scripting his own material for a while and then decided against it. I think it was the main reason he left DC in ’75, and a major one behind his leaving Marvel in ’78. Gary Groth and others have tried to push the line that Kirby left Marvel in ’78 because he didn’t want to sign a work-made-for-hire contract, but Kirby’s statements about it don’t support that.

Noah, Kirby worked with writer Steve Gerber on the first several issues of Destroyer Duck in the early 80s. That’s kind of a special case, since I think he did it mostly as a favor to Gerber.

My recollection is that Gerber wrote those full script, and that Kirby followed them relatively closely, although he would improvise here and there. (For instance, Gerber mentioned in a couple of interviews that Kirby came up with the corporate logo and slogan for the story’s “Godcorp” corporation on his own as a throwaway detail.)

Gerber’s and Kirby’s eccentricities dovetailed rather nicely, and delivered a pretty seamless collaborative comic (I think so, anyway). But I do think that Gerber was the driving force on that one.

Huh. I wonder what I’d think of that? I’m not a huge Gerber fan, but it sounds kind of interesting.

“did Kirby ever work with a scripter other than Lee post-60s?”

The first volume of Super Powers (1984) credits Kirby with plot and Joey Cavalieri with script (and art by Adrian Gonzales on all but the final issue). The second volume features all Kirby art, but credits Paul Kupperberg as writer.

Neither is good.

Super Powers, the crappy DC miniseries? I read those. They were horrible.

“And what do people think of Simon’s writing? I don’t know that I ever read any of those….”

Not even the original Captain America stuff? The best thing about that was the penis a disgruntled employee drew on Bucky in the hardcover reprint collection. Kupperberg was probably a better writer than Simon…

Come to think of it, several of Kirby’s DC stories were written by other people, towards the end of his 70s stint there — just to look at my nearby copy of DC’s Kirby Omnibus vol 2. Michael Fleisher wrote his Sandman, Martin Pasko his one issue of Kobra, and Kirby drew an issue of Richard Dragon that was written by Denny O’Neill. That last one is especially interesting for the die-hard Kirby afficionado; it’s the only Kirby story I’ve ever seen that has zero passion or commitment, and the only one that you could incontestably call hackwork. (IIRC, Gerry Conway wrote his final issues of Kamandi, too, but I don’t have that book at hand.)

That’s one depressing f*ing omnibus all round, really. By Super Powers 2, his last ever comic, Kirby was in serious decline.

Jones: That omnibus certainly contains some bad work from Kirby’s decline phase. But don’t sell it short—nothing that starts with 150 or so pages of Simon and Kirby Black Magic can be other than great.

Destroyer Duck is far from my favorite Kirby or Gerber. Someone who isn’t a fan of either wouldn’t think much of it, I’m guessing.

That said, the attack that Gerber gets off at John Byrne was hilarious, devastating and gross. (Byrne at the time described himself as a “company man” for Marvel and wouldn’t support Kirby’s quest to get his art back. Gerber created a character named “Booster Cogburn”, who was a creature without a spine.

Rob beat me to it. DD is nicely weird and twisted in parts, and it helps that both Gerber and Kirby were pissed off at Marvel, so they were on the same page there. But it’s very couched in “inside baseball” comics goings-on, and I don’t imagine you have much patience for that stuff.

(I kind of feel like rereading it now, myself. It’s been a while.)

R. Maheras

Difference is, Ditko was credited with “plot and art” on Spider-Man and Doctor Strange, certainly on the later stories. If Lee was willing to allow Ditko that credit, why wouldn’t he have done so for Kirby if he was doing the bulk of the plotting on his books?

Patrick — I asked that exact same question in my essay here, titled “Spider-Man: Wordless Destiny.”

https://www.hoodedutilitarian.com/2012/10/spider-man-wordless-destiny/

The fact is, Kirby, like Ditko, was doing most, if not all, of the plotting from 1963 onward.