Yesterday, Osvaldo Oyala posted an essay about the DC character Black Lightning, focusing particularly on how the characters’ two series (written by Tony Isabella) failed to address issues of race. Along these lines, Osvaldo wondered how race was handled when Black Lightning appeared in the team book, Batman and the Outsiders, during the 1980s.

I read those comics when they came out, and my memory was that race was barely mentioned, much less dealt with. I thought I’d double-check, though, and so I went ahead and reread Batman and the Outsiders #10, by Mike W. Barr and Steven Lightle titled…The Execution of Black Lightning!

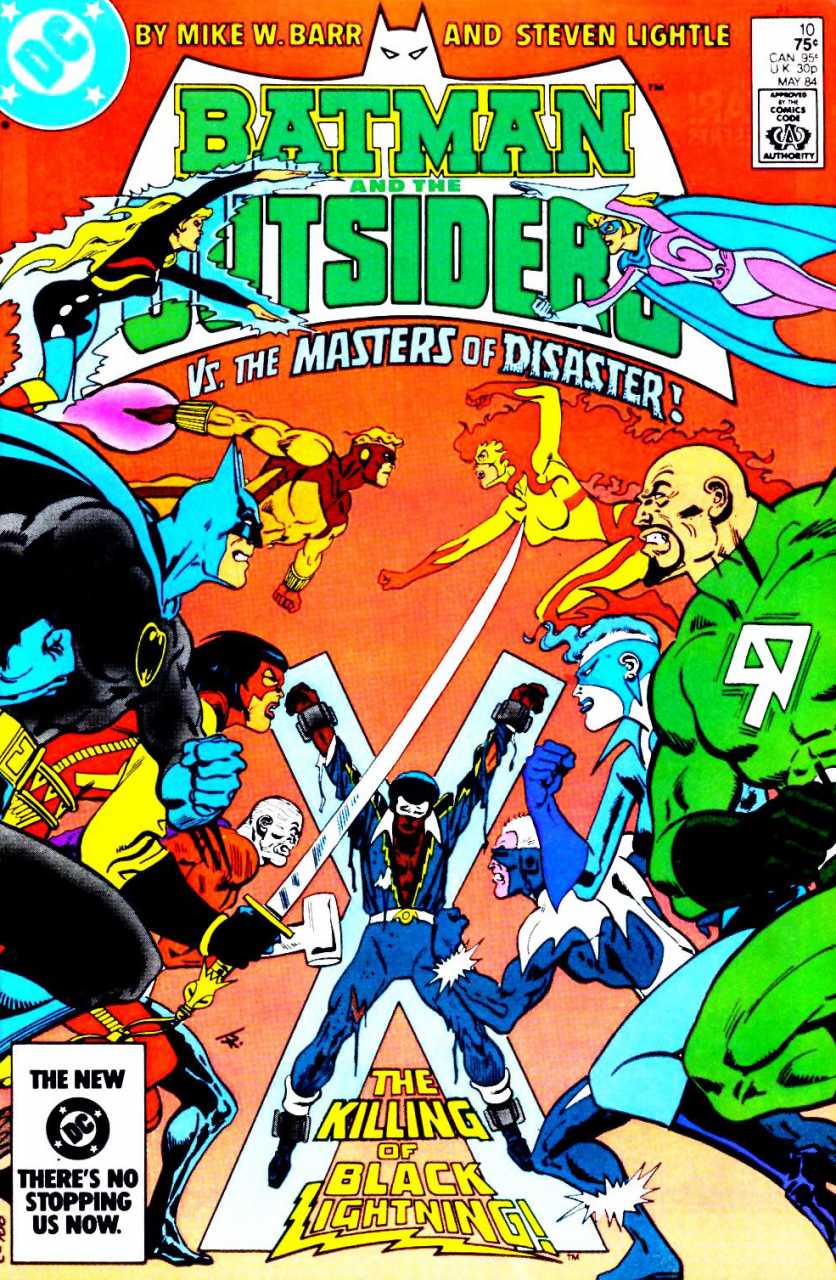

There’s black lightning, dead center, manacled to a structure which evokes a cross, clothes torn. It’s hard to avoid the evocation of slavery, and the link between African-American suffering and Christ. And yet, all those other characters on the cover do manage, somehow, to avoid it; the charged history of blackness in America hangs there suspended, while various costumed clowns square off for their tiresome Manichean good white guys vs. bad white guys battle, burying trauma under the high-pitched shuffle of silly costumes.

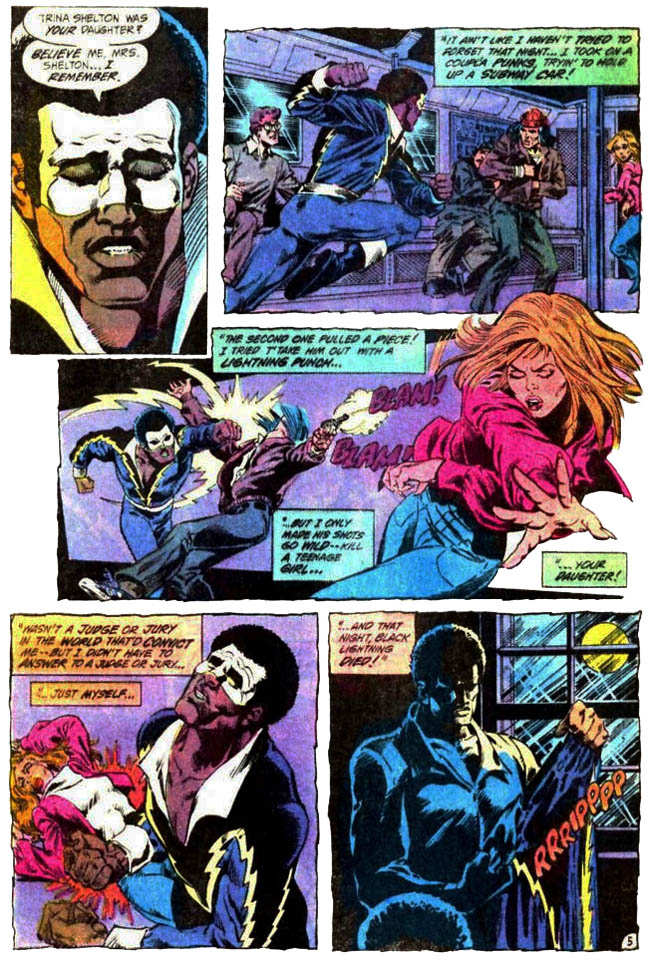

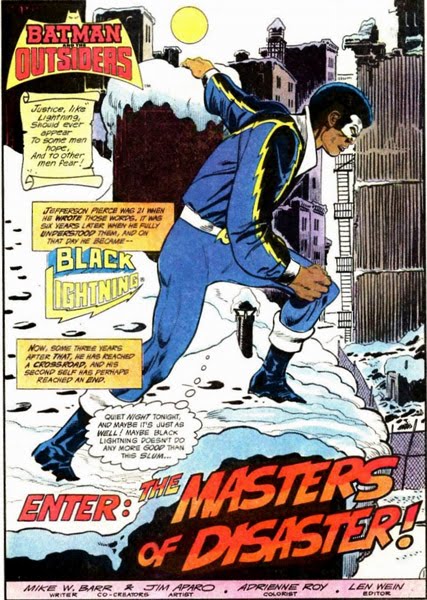

That’s fairly typical of how the comic as a whole works. Black Lightning’s blackness functions as an almost but not conscious theme, instantly and insistently deferred and repressed. The plot of the comic (such as it is) involves Lightning’s own traumatic tragic backstory — while he was fighting soem robbers on a subway car, a bullet went astray and killed a teenage girl named Trina nearby. Lightning blamed himself, and the trauma caused him to have trouble with his lightning powers, and to quite superheroing, until Batman convinced him to join the Outsiders (and helped him recover his lightning abilities). Trina’s mom, though, remained embittered, and so (as you will) she hired a team of supervillains to kill BL.

Again, race here flutters about, shooed away before it can quite settle. This was the 1980s, before the crack epidemic, but still, I think death by stray gunshot would be legible as a problem that particularly plagued gang-ridden minority communities. You have a black superhero, then, dealing with a violence and a trauma that is particularly associated with black communities.

And yet, the racial, and for that matter the class, connotations of the storyline are insistently disavowed. The girl killed by the thugs is white; her parents are presented as thoroughly middle class (with enough money to hire assassins, even.) Although BL was, as Osvaldo notes, originally presented as a hero particularly committed to inner-city and poor neighborhoods, he never appears to connect his particular, individual trauma to the trauma of those communities. Or, when he does, as in a couple page sequence in the previous issue, it seems designed specifically to replace the community with some guy in tights who can be taken out of them.

“Maybe Black Lightning doesn’t do any more good than this slum.” And that’s as much of a meditation as we get on race; inner-cities as throwaway metaphor for Black Lightning’s inner angst.

Similarly, the plot arc — a black man accused by middle-class white folks, chained and (almost) executed without trial — has pretty obvious parallels with African-American historical experiences of lynching. But neither creators nor characters seem to notice. The iconography (as on the cover) just sits there, as if daring the reader to make a connection. Black Lightning functions here not to present black characters or black experiences, but to studiously deny both. History and iconography are accessed simply to be denied; it’s an object lesson in how tokenism can be used not to grant visibility, but to more completely erase. The comic is almost a dare; how much African-American history can we pretend has nothing to do with African-Americans? The answer being, essentially, all of it.

In that sense the bulk of the Outsiders comics that don’t focus on BL are actually something of a relief. For the most part, he’s just another one in the crowd of superfolk, disinguishable by his costume and powers but not by anything else. In the black and white reprint volume I’ve got, even his skin color doesn’t set him apart. There’s only that Afro and the occasional more or less random lurch into dialect to remind you that the race-blindness here isn’t egalitarian, but simple, determined ignorance. They may claim they’re saving him, but none of those heroes on the cover is willing to look over at the black guy on the cross.

The line that sticks out to me in the panels above is “Wasn’t a judge or jury in the world that’d convict me. . .” Really? Of potentially reckless action by a black man that led to a white girl’s death? Really?

Also, while probably a result of the inconsistencies common to different writers at different times and on different books, BL’s use of slang when he is ostensibly talking to the girl’s parents is troubling on two potential levels:

1) Either he so dedicated to performing his “blacker” persona as Black Lightning that even when talking to the parents of a victim he does not drop the “street talk”

or 2) the writer just didn’t give enough of a shit to even note a distinction that is supposed to be part of how he performs his secret identity. In other words, even if he had decided to abandon his streetwise guise, wouldn’t then he go back to his English teacher “proper” talk?

Good point on the “not a judge” etc. That’s ridiculous.

And his use of slang in the comic seems completely arbitrary. Sometimes it’s there, sometimes not. That could be meaningful if he was using it selectively (and/or just falling into different accents depending on who he’s talking to), but it’s pretty clear Barr just isn’t paying attention at all.

That panel where Black Lightning is standing over Trina is very weird too… when you just glance at a thumbnail, it seems like he’s holding or cradling her. But really he’s standing over her, as she lies on the floor, but his fist just sort of punches through her. His hand blends into the negative space under her arm, the cuff matches the shirt… its just visually very weird. My hypothesis is that Black Lightning was supposed to be holding her, but then the artist had to back off, but the vestiges of the original composition are in there…

I’m wondering, though: what are our expectations for this kind of comic and/or storyline? Could you share, Noah, what made you pick up this comic to begin with? My expectations for the way race is represented in mainstream superhero comics is already pretty low and because I don’t read them regularly, I have a poor understanding of the genre’s conventions. But Nama tries to make the point in Super Black that regular readers would have been attuned to the small progressive measures and nuances throughout the evolution of black superheroes, even when the story as a whole seems to fall flat. (I find myself taking a similar approach to racial depictions in horror comics.) Not to excuse poor or insensitive storytelling, but I’m just wondering what is our criteria for judgment. It can’t just be that we are looking for Richard Wight and Ralph Ellison in comics form.

Kailyn, I think you’re right about that panel – it does look really weird!

It does!

Qiana, I’m interested in your point, because it corresponds with a lot of my experience in comics. Specifically, how comics consumers hyperbolize the qualities of a particular comic– whether it be how philosophical or scandalous or well– because they are prioritizing the ‘comics history’ context above all. As I understand it, you’re saying that a habitualized comics reader would appreciate how progressive BL’s portrayal is, within the context of comics history, even if its pretty regressive in a literature, or fine art, or political context. I’m not sure if this forgives it though, as much as shines light on the indulgences of the comics subculture.

I went back to this because Osvaldo wondered how BL was handled in BATO; this was his the storyline I’ve got that focused on him.

J.M. DeMatteis has a BL story from around this time that pretty directly talks about stereotypes called “Animals” I think. It’s not great, but you at least feel like he’s engaged with the issues. Black Panther at Marvel similarly isn’t brillians, I don’t think (from my tangential acquaintance with the storyline) but it’s not horrible. Blaxploitation cinema is hardly highbrow, and not Richard Wright, but manages to tell stories about black people that at least attempt to deal with race in ways that aren’t this aggressively stupid.

It’s definitely shooting fish in a barrel to some degree. On the other hand, even by lowbrow, hackwork standards, I think this is pretty impressively bad.

The only mainstream Black superhero I’ve ever heard praised by African-Americans is the Black Panther.

Though those Milestone characters look interesting.

Noah, no, I was asking what made you pick up the BL comic when it first came out in the 1980s. Were you already a regular reader of Batman and the Outsiders? Not that this “qualifies” your evaluation, but your familiarity with other BL issues by DeMatteis makes you at the very least, a more informed reader.

I mean, this is making me sound like the continuity police and prioritizing context above all – as you say, Kailyn – when that isn’t really my intent. But we know that the patterns and characterizations of genre fiction reward regular readers who become alert to the cues and modifications of formulas in ways that less familiar readers simply won’t catch. Bradford Wright likes to point out that Marvel was the first mainstream comic to put black faces in the backgrounds and among the crowds of bystanders. A small detail as milestones go, but if you’ve been reading comic after comic with a sea of white faces, it might be a big deal to you. Context does matter some, even if it is just one critical approach among many.

Ah, okay. Well I think I was 13 or something when this came out. Yes, I was reading BATO at the time; I liked a number of the characters, including Black Lightning, though why I liked him was somewhat unclear — I think it had something to do with the fact that he stood out as different (because back) and therefore somewhat less boring. I was disappointed though, for something like the reasons here — that is, they never actually did anything with him, and indeed didn’t seem to have any idea what to do with him.

From what Osvaldo says, I would say that the representation here seems to have gotten somewhat worse from that in BL’s own title. So…one context is that representations of race don’t actually always get better, or progress. Sometimes they go backwards.

I didn’t think you were prioritizing context above all! I thought you were more asking why bother with this piece of crap…which is a fair question, I think. And the answer is that Osvalo reminded me that I had affection for this character I guess. So as with most hate, there’s love sneaking around in the background there. Back when I was 12 or whatever, I wanted Black Lightning to be a worthwhile character. I’m still a little bitter that he wasn’t.

Why I wanted him especially to be a good character is perhaps a somewhat uncomfortable question. I grew up in a very racially segregated community (I don’t think I had a single black or Hispanic kid in my class all the way through high school) , and I think there was an attraction, or an interest in blackness that made black characters in comics interesting or appealing, perhaps.

Qiana, While I really like Nama’s book, I find his conclusions a little too optimistic. . . As Noah points out, “progress” in comics (and representation other forms of popular culture) is not a linear improvement in terms of greater and better representation. It is better or worse at different times with different characters and with different writers/artists – sometimes at the same time. So while, Nama is right that engaged readers are attuned to the small steps, they are also aware that the “forwardness” of those steps is often meaningless in the context of a larger incoherent approach to representation that unfortunately reflects a broader ambivalence with depictions of people of color (and women and the queer and the disabled).

I come to this kind of criticism from the perspective of someone who grew up “making do” with what I found in comics I love (often in unconscious ways that I was not aware of until I reflected on this later) and to some degree still do “make do.” That “making do,” that process of what Jose Munoz (RIP) might call disidentification or resistant reading is very useful in a culture that is not only hostile to difference, but is very often denies its hostility and turns it around on the victims – but it is also insufficient. So my taking the time to carefully read these things and hold them to a high standard (and ultimately, why shouldn’t we?) also has to do with teasing out what works or could work.

Osvaldo, I couldn’t agree more. I hope that you also see that my question was prompted by an interest in clarifying the critical apparatus that we use to evaluate these representations, not to suggest that the standards shouldn’t be rigorous. I am still trying to think this through myself.

I can relate to “making do” – it would be much easier to just laugh at and dismiss these characters and the crappy attempts to make race relevant, but we can’t; we want these stories to be worthwhile, as Noah put it. And so I agree that carefully reading them and talking about what works and what doesn’t is worth the effort.

In the context of Black male superheroes, as I recall, only Cyborg and Black Lightning appeared on a consistent basis during this period. Although both Cyborg and Black Lightning didn’t have their own titles, they operated on teams that had connections because Terra and Geo-Force were siblings and possessed similar powers and because the former dynamic duo team Bat Man and Robin served as team leaders. I didn’t collect Bat Man and the Outsiders (BATO). Interestingly enough, when the groups teamed up to fight a menace, Cyborg and BL has no exchange with each other.

I was more captivated by Cyborg because he was a member of the New Teen Titans, a title that I collected when they were known as simply, The Teen Titans. I also felt, at the time, that the art and concept of BATO was rather silly (they had a character named Looker, that seemed to be capitalizing on the popularity of Jean Grey/Phoenix). In addition, BATO had two minority heroes (Black Lightning and Katana) in a group called the Outsiders. This seemed offensive even to my 10 year old sensibilities. From the looks of these excerpts from the series and the comments, I was right on that call.

While the writers of the Teen Titans had Cyborg initially characterized as ‘the angry Black hero,’ his motivation for the anger was not rooted in race, but the accident that cased his disfigurement as well as his mother’s death. And, while Cyborg clearly falls into the category of the grotesque hero, he also falls into the John Henry trope of the often used Black man combined with machine (other Black heroes that come to mind is the original Deathlock from Marvel and DC’s Superman legacy character, Steel).

Black Lightning, should have appealed to me because he was ‘normal looking,’ compared to Cyborg, and as many critics have pointed out, BL didn’t talk like any Black men that I knew—his dialogue, at the time, was strange–the covers from BL short lived title did nothing to help matters.

Before Cyborg and Black Lightning, only Mal Duncan, who initially had no superpowers. Mal has an extremely bad entity crisis of his own. He adopted the identity of Guardian in the revival of TT #44 and then changed his identity 4 issues later to become Hornblower and, then, in the very next issue, went back to Guardian again). The only other Black hero outside of those mentioned here was Tyroc, who appears sporadically in the Utopian series Superboy and the Legion of Superheroes. While Wolfman and Perez’s Cyborg defied conventions, in my opinion Black Lightning did not. The stories in BATO seemed, to me, storyline driven, while the TNTT were largely character driven stories.

Most of the writers in 70/80’s didn’t know what to do with Black characters then and, after reading the recent Marvel event affiliated with The Avengers called Infinity, they really don’t know what to do with Black characters now (see Nightveil, Captain Universe, and Manifold (otherwise known as the super-chauffeur). While these characters are visually captivating, they contributed very little to the galactic story-line despite their seemingly vast powers.

I think Cyborg is still the highest profile black character DC has.

Yea, I would say Cyborg as well as John Stewart’s version of Green Lantern–interestingly enough it is not really because of their comic book appearances that they are the highest profile characters, but their presence cartoons. In Super Friends and Teen Titans Go (Cyborg) and Justice League, Justice League Unlimited (John Stewart/GL).

In Marvel, we have Black Panther, Storm, and Falcon. I can’t think of any Black female characters of note in DC except Vixen.