In their essay collection, Thinking about Animals: New Perspectives on Anthropomorphism, editors Lorraine Daston and Gregg Mitman assert that “humans, past and present, hither and yon, think they know how animals think, and they habitually use animals to help them do their own thinking about themselves.” Prompted by the ubiquitous manifestations of anthropomorphism in the arts and sciences, religion and folklore, advertising, and nature documentary filmmaking, the collection’s introduction charts the various psychological, religious, and ethic orientations toward ascribing human behaviors and characteristics to animals and asks: “Has the animal become, like that of the taxidermist’s craft, little more than a human-sculpted object in which the animal’s glass eye merely reflects our own projections?”

The question provides us with an opportunity to linger on the cat and mouse game at the center of George Herriman’s Krazy Kat. We might consider what the comic strip’s premise has inherited from Anansi, Aesop, Brer Rabbit, and other tales of talking animals in its serial run from the First World War to the Second, through Women’s Suffrage, the Great Depression, the New Deal, and the Segregation Era. Or we can reflect on how the strengths and weaknesses of Krazy Kat shape our interpretation of animal characters in the comic art and animation that followed Herriman’s lead. Felix, Mickey, Woody, and Fritz come to mind, but anthropomorphic animals as a trope touch a remarkable number of genres and styles, including titles such as Fables, Mouse Guard, Beasts of Burden, Pride of Bagdad, Bayou, Blacksad, and We3. And of course, given the subject of recent conversations on HU, we might even wonder: if it wasn’t for Krazy Kat, would we even have Art Spiegelman’s Maus?

While the animals of Coconino County engage a range of social identities and historical contexts against the love triangle between Krazy, Ignatz, and Offisa Pup, I’m particularly interested in the way anthropomorphism externalizes race in the comic strip. Daston and Mitman go on to make the point that animals are not merely “a blank screen” in anthropomorphic representation; their own actions and behaviors as animals bring “added value” to human projections. And so Herriman’s decision to undermine the well-known antagonisms between mice, cats, and dogs is meaningful, and not just because of the way the cartoonist endeavored to conceal his own mixed-race identity.

In Krazy Kat, the cat that chases the mouse isn’t driven by food or deadly sport, but by the kind of desire and affinity that is undeterred by species. In order to take part in this desire as readers, we have to accept what Jeet Heer characterizes as “the strange internal logic of the world Herriman created: we never ask why a cat should love a mouse, or a dog love a cat, since it seems natural. And this, perhaps, is where race becomes relevant.” Indeed, the comic strip’s defiance of the “natural order” brings to mind the discredited scientific theories used to superimpose racial categories onto a Great Chain of Being. Herriman’s anthropomorphism may dramatize difference, but not incompatibility and in the process, the comic affirms Krazy as America’s quintessential stray.

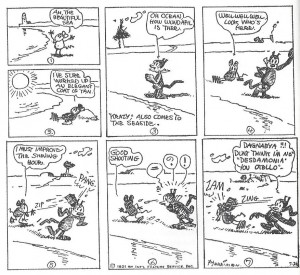

Heer points out that Krazy’s blackness becomes more pronounced over time, particularly with the appearance of his blues singing “Uncle Tom” cat. Added to this are several comic strips in which racism and white supremacy serve as the primary target of comedic reversals and impersonations. In one story, Ignatz falls for Krazy after the cat has been drenched in whitewash and the mouse longs for the “beautiful nymph” who is “white as a lily, pure as the driven snow.” Once Krazy washes off the paint, Ignatz’s outrage returns. In another instance, Ignatz tans in the sun and throws a brick at a confused Krazy who angrily responds in kind, saying “Dunt think I’m no ‘Desdamonia’ you Otello.” Krazy’s uncharacteristic behavior seems especially odd in this strip until one considers that he is not actually upset because a black mouse has thrown the brick, but because the brick-thrower is someone other than Ignatz. Certainly the Shakespearean allusion speaks to this tragic tangle of racial and gendered constructs.

Yet while the racial politics in examples like these are more explicit, I find them to be less compelling and somewhat disconnected from the “strange internal logic of the world Herriman created.” (Having discussed Herriman’s Musical Mose elsewhere, I would argue that this comic strip manipulates the concept of racial and ethnic “impussanation” much more effectively in the way that it sets caricatures against one another.) I believe that it is through the anthropomorphic structures of Krazy Kat and not through buckets of whitewash that Herriman achieves his most complex and multi-dimensional engagement with race and other “human-sculpted” realities. What is your take on how race is shaped by the anthropomorphic tropes in Krazy Kat?

Great article Qiana. I particularly want to hear more about how you think race is shaped in KK!

If Krazy and Ignatz (and Offisa Pup’s) relationship is the one stable element in the strip, does that imply that race maps onto it in a fixed way? The examples above all consistently paint Krazy black and Ignatz white. Or does this ever shift?

On the ‘strange logic’–

I actually think it makes perfect sense to confuse predatory and romantic desires…but maybe that’s just from growing up with KK’s descendants. The Loonie Toons characters were always trying to eat each other, which is more in keeping with real-world biology, but for all the visual richness of those cartoons, I never actually imagined Elmer eating Bugs and Daffy, or Sylvester eating Tweetie. The pursuit was always more archetypal… its similarly hard to imagine love for Krazy and Ignatz past the pursuit. And I think predatory drives go much deeper than just “I’m hungry, lets eat.” I’m not sure if the love triangle is the strangest part of Krazy Kat at all.

I am glad Kailyn brought up the Looney Tunes, b/c I thought about the chasing and hunting and desire that goes on in those cartoons as I read this and about the cross-dressing those characters frequently performed refracting the desire to possess in ways that highlighted the potential sexuality present in that desire. I know that as a kid I felt weird about “sexy” Bugs Bunny dressed as a woman and coming on to Elmer Fudd, or how Elmer Fudd was once dressed as a woman and was immediately chased by wolves in zoot suits (talk about anthropomorphizing race and conflating sexual desire!).

I hope that is not too much of a tangent, but I am not familiar enough with Krazy Kat to feel like I can comment with confidence (though I am hoping to soon fill that gap), but representation/performance of race and sexual/possessive desire go hand in hand (e.g. Lott’s work on blackface in Love &Theft. it might be interesting to do a reading of that anthropomorphism of race in Krazy Kat in conversation with performing race and sexual envy/desire.

Sooo… is the mouse Zimmerman, or is the cat Martin?

Kris, that’s awful. You’re awful.

Kailyn, I like your point about their love not extending “past the pursuit”…maybe the nature of their love is the pursuit itself? Really the only physical manifestation of their affections is the brick, both the sending and the receiving. And what do we do with that? Osvaldo, I think Lott’s work would actually be a really nice framework for reading the race and sexual/possessive desire in the strip, particularly given the way social identities are projected onto these animals. Lots to think about here.

To your other question, Kailyn, it seems that Krazy is most often depicted as a black cat and Ignatz as a white mouse, but Jeet Heer points out that Herriman has played around with this:

I think I may be getting Krazy Kat fatigue, so I’m not sure that I want to do anything else with this strip, but one thing I wanted to add in my post is that, thanks to one of my students, I recently discovered the graphic novel, BB Wolf and the 3 LPs (http://www.amazon.com/BB-Wolf-The-3-LPS/dp/1603090290). It takes the story of 3 Little Pigs and turns the Wolf into a black blues singer and the pigs into racist white southerners; the Wolf doesn’t start out “big and bad” but ends up that way when his family is killed… you see where this is going. I generally like comics like this. I loved Blacksad’s “Artic Nation” and I really wanted to enjoy BB Wolf too – but the characterizations are so heavy-handed that it made me appreciate Herriman’s strategic indirection and subtlety more than the moments in Krazy Kat when he inserts figures like Uncle Tom.

Pingback: Comics A.M. | Webcomics and proper credit in the viral age | Robot 6 @ Comic Book Resources – Covering Comic Book News and Entertainment

I’m not sure that we’ve addressed your question, Qiana. Jeet Heer’s comment that you quote in your response is one that I use in class when teaching Krazy Kat to reinforce the idea that race is a social construct.

But you seem to be getting at something different…how is race represented through the anthropomorphic representations in Herriman’s comic? Did I get that right?

I’ve taught Herriman’s work a few times, and in our discussion of race and Herriman’s work, my students and I have never framed our conversation in this way. I know the format of your posts is to end with a question in order to facilitate a conversation, but I’m really intrigued by your penultimate line: “I believe that it is through the anthropomorphic structures of Krazy Kat and not through buckets of whitewash that Herriman achieves his most complex and multi-dimensional engagement with race and other “human-sculpted” realities.” I would love to hear more about this idea.

Tim! Thanks for joining us over here at the new space. If my thoughts on this post sound tentative and unfocused, that’s not by accident. I’m still figuring out what I think. To take an image like the one of “Uncle Tom” playing the banjo at the top of this post – when I saw this, I wondered if what racializes Krazy in the strip are details like the fact that he has an uncle named after a well-known black American literary character or simply the fact that he is a cat (who loves a mouse, is loved by a dog, etc). Is the “mark” of difference Krazy’s species/fur color or is it the associations with cultural artifacts like the blues? We can say it’s both. But personally, I like the way Herriman plays with the species differences. I think the strip’s premise offers enough of a commentary on racial/gender structures that Herriman doesn’t have to have Ignatz tan in the sun for us to “get it.” (Do mice tan?) Ultimately Herriman is going to draw from every potential gag at his disposal – this is a humor strip. But I guess I’m also concerned that critics who are looking for racial metaphors in Krazy Kat will cite the scenes with the whitewash trick or the Uncle Tom character and overlook the fact that the metaphors are already there and always relevant – in every strip.

Qiana, you know I’m going to follow your work wherever it goes on the interweb. That you’re hanging out here at the HU is just a bonus.

I think I get what you’re going for in your follow up to my comment, and I find it so interesting that I want to play around a bit to see and pose some questions of my own to your questions.

If we bracket off the sorts of cultural references (blues) and overtly radicalized visual metaphors (whitewashing and tanning) that you mention, then you’re suggesting that there is an implicit comparison to race in Herriman’s anthropomorphic characters that form the strip’s love triangle. This is a really provocative idea to me, and it’s causing me to think back to my long ago reading of Eric Lott’s work, which is now made murky by the passing years. Specifically, some thoughts are beginning to bubble up about the intersection of race, power,and desire. What sorts of implications would Lott’s work have, for instance, on our thinking about the nature of the attraction that Krazy feels for Ignatz? The repulsion/attraction that Ignatz feels for Krazy?

Hi, Qiana.

Great post! Exploring race in Krazy Kat is really complex, and I’m glad you tackled it.

I have a question about the quote from Jeet Heer: “the strange internal logic of the world Herriman created: we never ask why a cat should love a mouse, or a dog love a cat, since it seems natural. And this, perhaps, is where race becomes relevant.” I’m not sure that we don’t ask why a cat should love a mouse. I think that the (real world?) ideology of cats chasing and eating mice is too powerful to ignore, so when that expecation is not met, we ask why it isn’t. And I think *that* is when race becomes relevant because it stands in for species difference.

Your comment to Tim is also a good one: “But I guess I’m also concerned that critics who are looking for racial metaphors in Krazy Kat will cite the scenes with the whitewash trick or the Uncle Tom character and overlook the fact that the metaphors are already there and always relevant – in every strip.” Sometimes in gender studies, we ask whether gender is always relevant and whether it is always determinate. Do we always know what gender a character is? Do we always know when a contextual cue suggests a specific gender? Is it always important that they should (or do)? Is it the case in Herriman’s Krazy Kat that race is always relevant? or maybe potentially relevant?

I love this line: “Herriman’s anthropomorphism may dramatize difference, but not incompatibility and in the process, the comic affirms Krazy as America’s quintessential stray.” This idea of “impussanation” also interests me in terms of dialect and desire. There seems to be a very Michael-North dialect-of-modernism dynamic in Krazy Kat where the hybridity of language also becomes a boon of these interspecies interactions. Edna St. Vincent Millay wrote some of her private correspondence in the voice of Krazy Kat, but I didn’t think through the racial implications of that ventriloquism.

Qiana: I hope your Krazy Kat fatigue wears off because you have what I think is a more interesting and consequential approach to racial identity in Krazy Kat than anything published so far, definitely material for a book or at least a seminal article. My first thought reading your post was that readers will focus more attentively on the speech patterns of the characters (they seek anchoring in dialectal markers, etc.) if the visual markers of identity aren’t immediately obvious. But Krazy’s speech patterns read as those of a Brooklyn Jewish woman (the gendering of his speech matters) sprinkled with a mix of other dialectal features and features associated with the speech of non-native speakers of English. Each cue to racial identity is displaced by other cues and the verbal and the visual seem to be at odds with one another, at least where Kat is concerned. The reader seeking anchors of identity encounters a constant and bewildering whirligig of displacements. But then there is also the Mock Duck character (whose “oriental magic” is responsible for the body switch Frank discusses in his post). A “Mandarin” duck as an anthopomorphic marker of Chinese identity is all too obvious and Mock Duck’s speech patterns are clearly those of a Chinese immigrant, and constitute some of the more offensive caricatures in all of Krazy Kat. So what do you make of Mock Duck as far as the anthropomorphizing of racial identity is concerned?

These are incredibly helpful comments and such thoughtful questions. I can shake off this Krazy Kat fatigue for a bit longer. I needed some time to think about this. I have been playing around with some notes for an article about race and anthropomorphism in comics, and I’m realizing now that KK is going to be more important than I initially thought.

Tim asks: What sorts of implications would Lott’s work have, for instance, on our thinking about the nature of the attraction that Krazy feels for Ignatz? The repulsion/attraction that Ignatz feels for Krazy? I will need to read Lott again as well, but I think the repulsion/attraction dynamic is essential to a reading of Herriman’s strategic use of the anthropomorphism; it makes explicit the complicated and ambivalent desires that shape how blackness/whiteness has been constructed historically.

I think the consequences of this reading can become somewhat problematic for talking about Krazy as he becomes increasing identified as African American over the course of the strip. It makes it more difficult to characterize the black cat’s attraction simply as “unrequited love” and just leave it at that, particularly when he/she is treated with such cruelty in return. (Or maybe it’s a perfect metaphor for race and American history after all.) I should also add that the violent nature of their relationship would be right in line with Jared Gardner’s reading of early newspaper strips that continually “celebrated the modern body’s resilience” through pretty grim and gory slapstick humor.

Having said all this, I very much appreciate Frank’s nudge to be more precise: perhaps race is not always determinant in each strip but it remains potentially relevant, even when we bracket off the black cultural references and visual metaphors. Nor can we say this about every comic featuring cats and mice – Herriman’s particular choices matter!

Michael, I take your point about the way “each cue to racial identity is displaced by other cues.” This is still another place where I think we should pay attention to Herriman’s fascination with impersonation . I think this could yield special insight into moments, for instance, when Krazy’s speech patterns and dialect change too. Doesn’t all identity in this strip amount to impersonation of some kind or another….? We never know who the “real” Krazy is… I agree, though, that the Mock Duck is one of the more offensive caricatures; I would need to see more of what Herriman does with this figure, but he doesn’t seem to offer any of the meta-textual elements that usually double back on the use of these kinds of stereotypes.

Cat, I would LOVE to see some of that Edna St. Vincent Millay’s ventriloquized correspondence! I will email you!!!