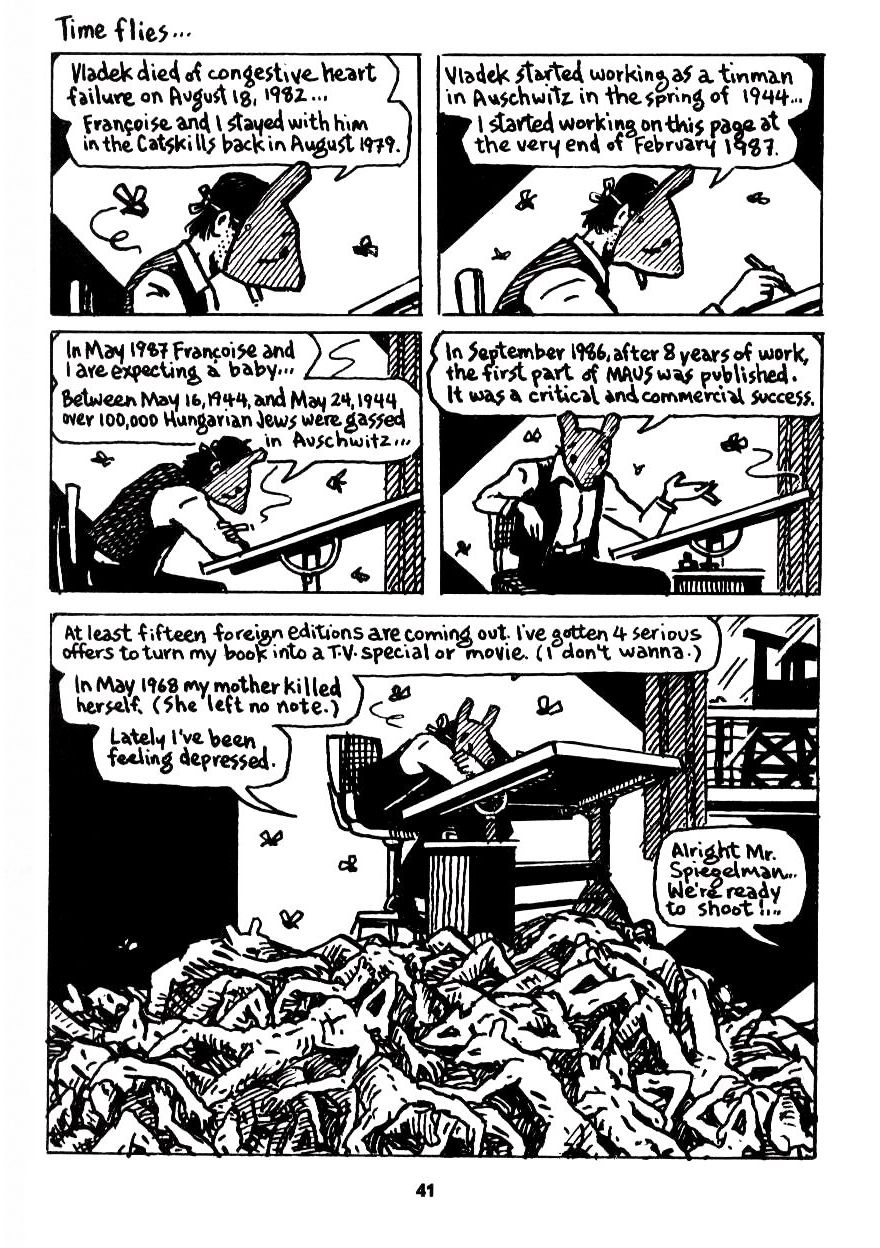

This is probably my least favorite page in Maus.

This page doesn’t have the design problems that I taked about over here, and, which Mahendra Singh elaborated on.

The second page is cramped and confused; the first is not a masterpiece of design or anything, but the simple four panel grid at the top is effective; the flies the visual tip off to the gruesome reveal of the corpses around the drawing board.

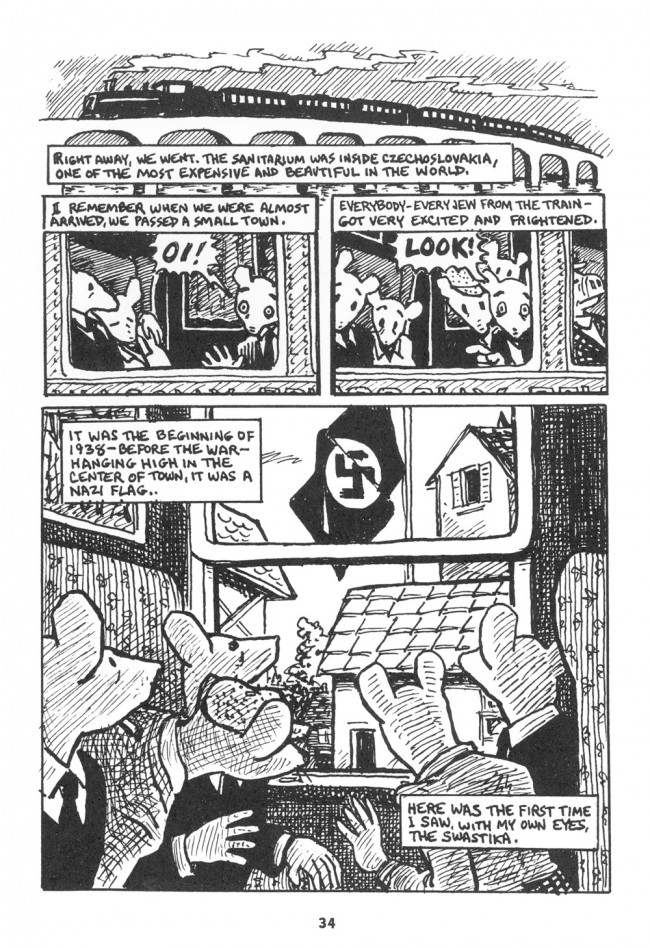

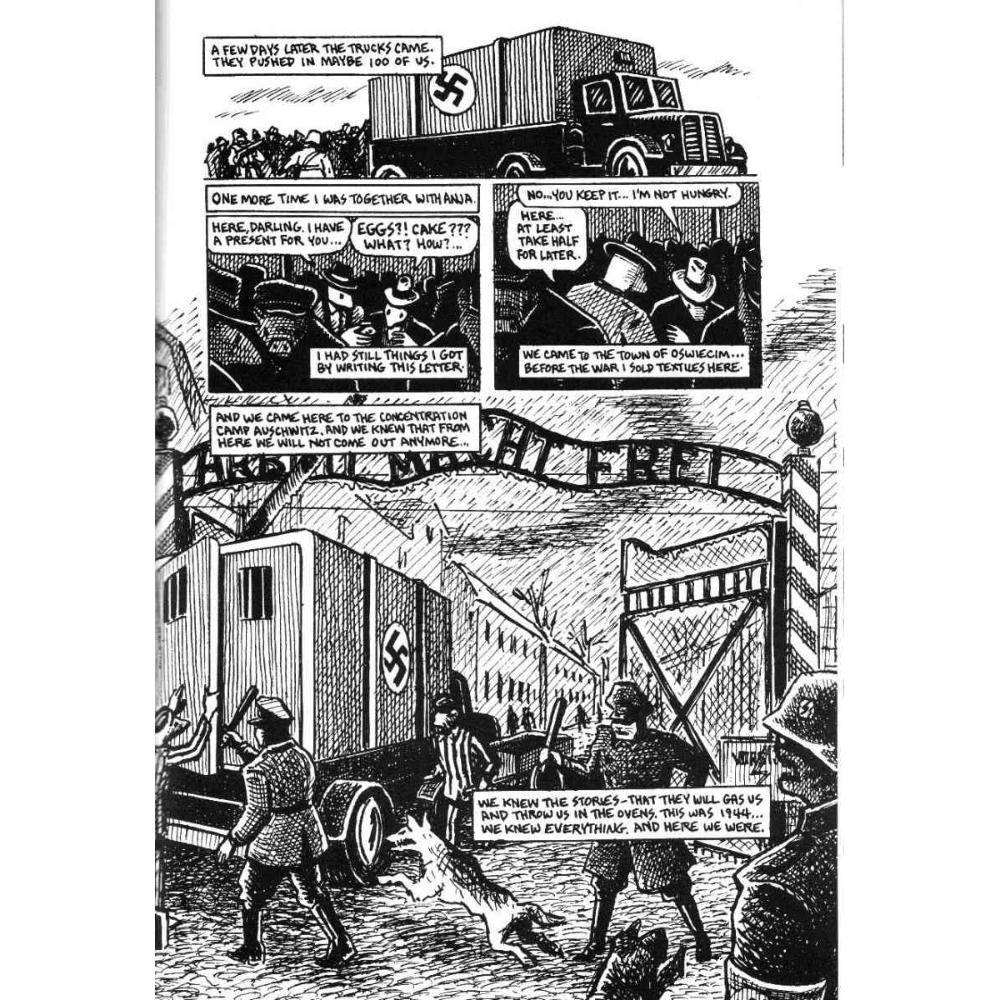

What’s interesting, though, is that, while one is sub-competent and the other is effective, both use the same basic formula. You also see it here:

In each, the page is set up as a reveal. The top visuals keep your eyes focused on neutral images, and then the bottom opens up into the horrible truth. That horrible truth is always the same truth; namely the Holocaust, symbolized with a crude obviousness either by the (poorly drawn) Nazi flag, or the Auschwitz gate, or (most viscerally) by a huge pile of dead bodies. the importance of the Holocaust is emphasized each time both by its position as revelation, and by its scale. In his page design, Spiegelman tells us, over and over, that the Holocaust is huge and that it leaps out at you.

That is not, I would argue, an especially insightful take on the Holocaust; it turns it into a pulp adrenaline rush. Those pages each seem like they’d work as well, or actually better, if you substituted Dr. Doom for the Holocaust in each case. IF you’re going to set up a supervillain behind the curtain melodrama, best to be talking about an actual supervillain. Hollywood effects work best with Hollywood content; trying to add drama to an actual genocide comes across as cheap and presumptuous.

Interestingly, Spiegelman himself is somewhat aware of this, and on the page I’ve shown here, and in the following page, he tries to address it.

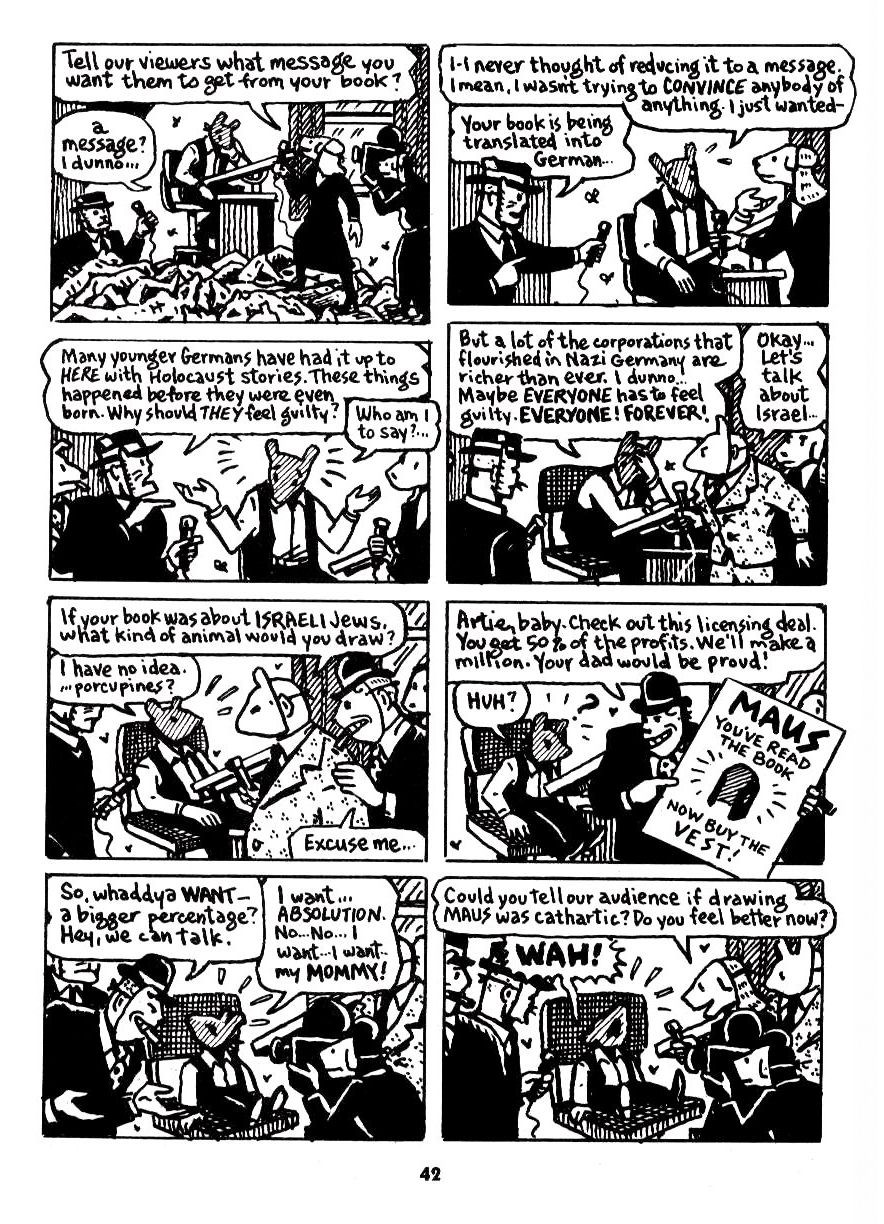

Spiegelman here is discussing, and decrying, the Hollywoodization of his book. These pages are from the second part of Maus, after the first part had gone the pre-Internet version of viral. The “reveal” of the final panel is both of the corpses and of the book’s success — the foreign language editions, the TV and movie offers. You could see the bodies as symbols of Spiegelman’s innocent alt-comix purity — a kind of spiritual death, underlined by the reference to his mother’s suicide. The off-panel declaration that “We’re ready to shoot!” links the media explicitly to the Nazi murderers; Spiegelman, as tortured artist besieged by popularizers and reporters, is positioned as a tormented victim of the gas chambers.

Defenders of Maus will no doubt argue that these pages are ironized. For example, Eric Berlatsky (that’s my brother!) writes:

Spiegelman is sure to implicate himself when he depicts Artie at the outset of chapter two of Maus II. Sitting at his drawing table, in front of television interviewers, Artie discusses the commercial success of the first volume of his book while sitting atop a pile of anthropomorphic mouse corpses. He is depicted not as a mouse, but as a man wearing a mouse mask, performing Jewishness for commercial gain. The simultaneously humorous and threatening depiction of the American advertiser offering a license deal for Artie vests (“Maus. You’ve read the book now buy the vest!” [42]) indicates how Artie (and Spiegelman himself) uses the past not merely to recall it in the present, but for his own profit and on the backs of the Jews his book is purportedly “remembering.” Artie displays a questionable connection to the past in order to participate in the circulation of power and profit.

Eric, then, suggests that Spiegelman is intentionally undermining himself; that he’s implicating himself in the marketing of the book and the performance of Jewishness.

I’d agree that the page raises the questions that Eric discusses. But is the effect really to undermine Spiegelman? The sympathy in that second page remains resolutely with Artie, who is being “shot.” He is the sensitive artist/victim (reduced to actually infantilized crying at the end) while callous reporters and interlocutors try to make a buck or score stupid points off the corpses stacked around his desk. The shallowness and duplicity of the media is emphasized by Spiegelman’s use of masks here; because they are drawn in profile, where we can see the mask-strings, the reporters comes across as macabre and deceptive.

Spiegelman is drawn in profile on the first layout, too. You’re in his head though, and he’s alone; it doesn’t feel like he’s concealing something, but like he’s trapped; the mouse mask victimizes him, and connects him to the dead victims (who aren’t wearing masks.) And then from that bottom reveal and through the next page, Artie is drawn mostly looking out at the reader; you can’t really see the mask. It’s as if the dead bodies have made him a “real” Mouse. In addition, the presence of the reporters ends up being validating; the contrast between their clear masks and his “natural” features shows clearly who has the right to speak — they’re crass desire to commercialize the corpses around his desk positions Artie as feeling caretaker; the only one who truly understands the horror. Thus, the dialogue is mostly the reporters asking aggressive questions and Artie as genius artist undermining them with wit and humble brag, followed by sensitive breakdown. The low point is probably when Artie blithely suggests he would draw Israelis as porcupines — a smirking one-liner that both dismisses the very real problem that Israel poses for Spiegelman’s Jews-as-mice-as-victims metaphor and glibly ties into ugly Zionist narratives positioning Israeli aggression as righteous defense.

The real failure of these pages, though, is Spiegelman’s utter refusal to grapple with his own responsibility for the commodification he’s supposedly decrying. IF you really don’t want your Holocaust story to be easily consumable, there are ways of doing that, from Celan’s impenetrable poems silence to Philip K. Dick’s oblique, quiet puzzle-box The Man in the High Castle. The critical and commercial success of Maus is not an accident; it’s the result of the deliberately unchallenging way in which Spiegelman presented the material. And that makes his wailing about the burden of success (which he, again, explicitly compares to the horrors of Auschwitz) insupportably presumptuous. The page itself, with its build-up to the big gothic reveal, uses pulp tropes to dramatize the Holocaust. The quite clichéd juxtaposition of feeling artist and unfeeing reporters/media is also an easy cultural narrative. Even the revelation of Spiegelman as man, rather than as mouse, doesn’t so much undermine the iconography (we still get the shock of anthropomorphic corpses) as it shows us the hand behind the image. Tortured genius is hardly a new marketing meme.

In short, Maus, in numerous ways, is an effort of deliberate middle-brow popularization. And part of that popularization is the elevation of Spiegelman himself; the genius interpreter, speaking from his pain as corpses overwhelm his drawing board. The bitter irony of Maus’ success is that the book’s defenders end up in the position of Spiegelman’s masked Nazi-like philistines,scrabbling joyfully amidst the corpses. And from the pile, finally, they lift Artie himself, circled by flies, the genius who realized that if comics marketed genocide, genocide in return would market comics.

Regardless of how commercialized it was intended to be, the “middle brow popularization” that was MAUS probably would’ve connected far better to my Midwest suburban eight grade advanced reading class than Elie Wiesel’s NIGHT did. And, speaking from experience, those were the kids who needed to understand the story of Nazi oppression more than anyone.

Yeah, that’s a totally reasonable response. I think there’s a case to be made for Maus as worthwhile popularization. The problem I have is that much more is generally claimed for it — and that, in these pages, Spiegelman pretty explicitly disavows his success, basically blaming others for it (and comparing his angst over that success to genocide).

You make some good points, Noah, but aren’t you the guy who loves Inglorious Basterds, the all-time pulpiest take on the Holocaust?

Spiegelman’s hand-wringing on those pages struck me as insincere, as well. That was partly because he never dwelt on his simultaneous use of his father’s story and portrayal of his father as a jerk, which seemed like an obvious ethical quandary. He repeated the sparring-with-crass-media-buffoons shtick in In the Shadow of No Towers, which showed him sharing his iconoclastic views on 9/11 with an outraged t.v. host.

Even though I’m not big on Spiegelman’s self-portrayal or his animal metaphors, I still think Maus is a good book. Spiegelman’s father had a worthwhile story and he told it pretty straightforwardly, despite the animals.

Speaking of Elie Wiesel, I think Night has also been disparaged as a schlocky, middlebrow treatment of the Holocaust. (I read it a long time ago and don’t remember it well.) I definitely have more respect for Spiegelman than for Wiesel–as annoying as the former’s whining about Bush in the No Towers book may have been, I’ll take it over Wiesel personally meeting with Bush and encouraging him to invade Iraq. Wiesel also has a creepy Israel-worshipping thing that I doubt Spiegelman shares (I didn’t see the porcupines line as any kind of justification for any Israeli actions).

Your extensive analysis of these pages almost completely ignores Spiegelman’s reduction to infancy at the end with the exception of one minor parenthetical aside, quite sensibly because it undermines your charge of Spiegelman’s self-aggrandizement as a romantic, tortured artist.

My reading: Spiegelman is dramatizing his failure as the media personality made by the unlikely succcess of Maus (unlikely because the anthropomorphic conceit and the medium itself could easily come across as trivializing). His project is built on a heap of corpses. He has no advice to the world for a way forward. The visual conceit breaks down under scrutiny. The subject itself reduces him to the child who first encountered the Holocaust through his parents’ words.

Wiesel is a really problematic figure (he was involved in some efforts to downplay the Armenian genocide too, if I remember right.) I read Night a long time ago, and thought it was pretty good, though not great.

I’m not against pulp per se; my point is that Spiegelman doesn’t acknowledge how he’s using it. I think Basterds is a lot (a whole lot) more thoughtful about its use of genre and representation. Its very much about movies about the Holocaust rather than (or in addition to) about the Holocaust itself, and about how narrative can give us a purchase on trauma which is exhilarating, albeit false and hollow in a lot of ways.

I just feel like Tarantino’s a lot more honest about his commitments and his love of pulp. Spiegelman uses melodramatic effects and then wants to disavow what they do and why they’re appealing.

___

Re Spiegelman’s infantilization…it doesn’t undermine his stance as tortured sensitive artist. It embodies it. He’s the suffering sensitive victim being persecuted by these big bad media people.

And sure,he says he has no ideas about the way forward. Thus the humble brag; he’s just a traumatized seeker, honestly seeking answers and absolution. Gag me.

I find the practice of dropping the panel boxes for a big scene to have a gentle, storybook quality in keeping with the storytelling mode in which the author receives the material. If Spiegelman was aiming for pulp theatrics he could have gone much further: the cinematic staging of manga, the Miller/Dark Knight style of cutting to a full-page splash, or the panoramas of carnage in Alan Moore’s Watchmen and Miracleman.

Spiegelman is also capable of a tortured, expressionist style as in Prisoner on the Hell Planet or The Wild Party (and an admirer of artists like Cole and Krigstein) so a pulpy, melodramatic treatment would have been well within his means.

A gentle storybook quality where the big reveal is a pile of corpses or the gate of Auschwitz?

I think we’re just going to have to agree to disagree.

I disagree re: the infantalization, I don’t think it frames him as a tortured or misunderstood artist, I think it demonstrates Spiegelman’s inability to handle his shit. He presents himself as a child crying for his mommy not because he wants present himself as a victim, but because he wants to convey how in over his head he feels, he juxtaposes his own success critically and financially against his failings artistically and personally. One of the main themes of the book is a conflict between human suffering and the kind of capitalist actions that his father takes to survive(and in creating the book he is taking); which is what the masked pages explore, you missed out the following four pages of Art with his shrink which I think you should definitely consider as they contextualize two you have shown in quite a different light. The pages express his feeling of inadequacy in comparison to his father (both as a holocaust survivor and as a businessman) indicate and the way in which Spiegelman feels that for something to be a success it has to be commercially successful, as those are the terms his father thought in (in that to “survive” in a world of capital, commercial success is an indication of capability to survive). Here he describes his inability to properly consider the holocaust, to understand the victims (and his father), and to understand his father’s survival as something other than a myth of his father’s success.

I read the following pages while doing this. They seemed like fairly boilerplate Holocaust/evil discussions; survivor’s guilt, etc. It’s fine, but I don’t think it changes my reading of this page that much.

These pages don’t show Spiegelman unable to handle his own shit. They show him unable to deal with other people’s crassness. He’s besieged on a mound of corpses.

I don’t think he’s besieged by them, he’s sat on top of them, they’re not attacking him, the imagery is a pretty clear implication that he’s exploiting them for his success. It’s about guilt. The revealing that Art was compared to his father as a child, with his father as an admirable “survivor” and figure of success does change how those pages read. We learn that his anxiety over success isn’t simply his profiteering from the holocaust, it’s an anxiety regarding him knocking his father down to build himself up, there’s a sense that he feels that he’s taking away from his father (and other survivors) to gain the commercial success which his father impressed the importance of on him.

His strife and reduction doesn’t appear to just come from how other people are handling the book and its depiction of the holocaust, but also from his own inability to depict it; “even when I’m left alone I’m totally BLOCKED”, “part of me doesn’t want tot draw or think about Auschwitz. I can’t visualize it clearly and I can’t BEGIN to imagine what it felt like”, and his general misconception about the idea of Auschwitz as a win or lose situation. He’s showing his own flaws and failings here, and although Spiegelman doesn’t quite go so far as to condemn himself, there are definitely feelings of guilt present, which he indicates stem from his father.

The guilt and infantalization stemming from his father (and his failings, which he largely blames on his parents) makes far more sense than him just throwing that child image out randomly, it’s also strongly implied that this is the source on page 207 when by listening to his father’s voice to write from. (I also just noticed that in the second page you look at, he is only depicted as a child after the business man says “Your dad would be proud.”; referring to the commercial endeavors surrounding the book.)

Also when you think of the innocent and pure of heart artist, set against the harsh media world, you don’t think of a screaming child. There’s nothing heroic about an adult acting like a child, it’s not even something we empathize with really, it’s generally characterized as kind of pathetic.

Artists are often presented as childlike, and not in a bad way. I don’t know; it’s supposed to be pathetic, but also vulnerable. And it’s difficult not to see it as referencing victimization when you’ve got that pile of corpses sitting there.

I’d argue the presentation of artists as childlike in a positive way is usually in reference to the childlike and playful elements of creativity, its not usually in terms of pathetic vulnerability, what’s generally lionized is raging against the machine, not crumbling when confronted by it.

I think it’s a bit of both so far as him depicting himself as a victim, on the one hand he’s clearly on top of the corpses, but he’s also within Auschwitz, he’s built his success on the corpses but he’s still trapped within the same institution as those victims, it’s ambiguous. I’m not sure I agree with what you’ve said about him being in some way a true mouse by connecting him to the victims, what you read as a pulp flashy reveal, can just as easily be read as him covering up the corpses till its revealed in the half page panel. Indicating how hypocritical his line; “lately I’ve been feeling depressed” is in his place of privilege over the dead, is.

Noah said,

“A gentle storybook quality where the big reveal is a pile of corpses or the gate of Auschwitz? I think we’re just going to have to agree to disagree.”

A relaxed, expansive storytelling style to frame unimaginatively horrible events as opposed to the heavy metal guitar solo-style of the comics I mentioned that would attempt to rise stylistically to the level of the horror. Vladek’s narrative voice, the frame of a father telling his son stories, dominates the more scenic treatment of his recollections.

The volley from the media suggested by the “ok, shoot” line reduces Spiegelman not to a corpse but a child (a condition addressed in very comfortable middle-class fashion by a visit to a psychiatrist.) This is in keeping with the theme present from the beginning that no adversity Spiegelman encounters can ever compare to what his father experienced in the Holocaust. If the goal was self-aggrandizement Spiegelman could have had the media make him an inmate or even a corpse- something like what he did as a younger man with Prisoner on the Hell Planet. Likewise, Spiegelman is regularly shown bickering with his father in the present, in scenes which emphasize not only Vladek’s difficult personality but Art’s own extreme irritability and constant complaining- “wah, you threw my coat out and gave me a new one” is quite a contrast with scenes of the Holocaust. This is a romanticizing self-portrait?

There’s nothing subtle about the flies expanding out to a giant pile of corpses. That’s really quite, quite thudding.

I’m not sure how you can see the statement that we’re ready to shoot juxtaposed with a pile of corpses as not referencing violence.

Showing your faults is a very basic confessional literature way to get the audience on your side. It’s not a romanticizing self-portrait in the sense that it papers over Artie’s flaws. But those two pages present the commercialization of the Holocaust as someone else’s fault without interrogating the ways in which Spiegelman’s narrative is a popularizing one. He’s the artist being persecuted by crass media jerks, and his angst is linked to Auschwitz. I find that fairly repulsive.

More nonsense, Noah. “Pulp tropes” and “middle-brow popularization” suggest a trace of snobbery that is not consistent with the virtues of your other critical writing. You’ve used them here, it seems to me, because they are rhetorical cheap shots. And your reading remains remarkably tone-deaf with regard to Spiegelman’s self-mockery, which you persist in seeing as mere self-aggrandizing BS. Your reading of MAUS, in other words, remains aggressively flat.

“Artists are presented as childlike in a good way”—-maybe you can explain how being infantilized, in being presented as pathetic, naive and/or vulnerable isn’t negative.

You’re so funny, Charles. You jump in to rail against my tone with barely a pretense to civility, attacking my lack of specificity with a barrage of loaded terms and with only the vaguest effort to engage what I said. Academic heal thyself, yes?

I’m not attacking pulp tropes qua pulp tropes, incidentally. I’m saying that he blames the popularity of the book on misreadings of a callow public without acknowledging or dealing with his own popularizing impulses. I find his page design pretty clumsy, but, that’s a relatively venal sin; it’s the clumsiness coupled with blaming other people for the results of the clumsiness which is really insufferable.

James, the meme of artists as vulnerable in comparison to callow media jerks seems fairly self-explanatory. Naivete here is specifically figured as lacking knowledge of money; he’s a wise fool. I’d also argue that he isn’t actually presented as pathetic; he wins the arguments throughout the page, and gets in all the witticisms.

There’s a fine line between self-deprecation and narcissism, and I think it’s pretty common for artists to put themselves down in a way that, whether they’re conscious of it or not, actually implies a high self-opinion. (A recent example is Marc Maron’s horrible t.v. show, about what a lovable neurotic jerk he is.) And whatever Spiegelman’s intent was, I think he really comes across as full of himself in Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers, and that strip where he talks over Charles Schulz’s head.

Yeah. How can you read Spiegelman saying, “I have no idea — pocupines?” and not be certain that he thinks he’s the smartest guy in the room?

So the artist can’t be a narcissist. He should be ‘perfect’, modest, or something like that. A role model, maybe for kids. Or for politically correct adults.

Yeah, I’m politically correct and in search of modest role models. That’s exactly why I’m annoyed by the pseudo-self-deprecation of artists who clearly think they’re awesome.

what’s wrong with that?

I like lots of narcissistic art, from cock rock to rap. There’s something particularly unpleasant about humble bragging about the Holocaust though.

So the critic can also be narcissistic and show he’s the smartest guy in the room. I asked Jack, he brought up the subject of narcissism —but it’s OK, Noah. All right.

I’m not very interested in moral judgments of an artistic work, I prefer the aesthetic judgments. Maybe that’s why I stopped reading this site. Good night, and good luck.

The idea that morality and aesthetic can somehow be separated, and that they should, is absolutely a moral position. And the suggestion that you somehow should not think about morality in a work like Maus, which is basically all about morality, strikes me as ridiculous.

“What’s wrong with that?”–I guess I think it’s smug. That’s how I’d describe the top strip in this piece, which is apparently supposed to be funny or say something about Charles Schulz: http://tinyurl.com/lewf6cg. So it is an aesthetic judgment. You’re free to shoot back that I’m smug, too, but anyway, that’s a side of Spiegelman’s work that I don’t like.

Noah says,

“There’s nothing subtle about the flies expanding out to a giant pile of corpses.”

Why, yes, and you’ll notice that this scene is not one of Vladek’s reminisces but a scabrous allegory.

“I’m not sure how you can see the statement that we’re ready to shoot juxtaposed with a pile of corpses as not referencing violence.”

That’s not what I said. Of course the entry of the reporters with the line “we’re ready to shoot” juxtaposed over images of Auschwitz evokes a firing squad. What I said was that the onslaught reduces him to a child rather than a corpse, in keeping with the theme of a life of inescapably trivial problems in comparison to the Holocaust.

“Showing your faults is a very basic confessional literature way to get the audience on your side.”

Well, then he can’t win, can he?

“…those two pages present the commercialization of the Holocaust as someone else’s fault…”

I don’t get “someone else’s fault” from placing the classic cartoonist’s self-portrait at his drawing board atop a mound of corpses. Said image could as easily be deployed in an attack on Spiegelman.

“…without interrogating the ways in which Spiegelman’s narrative is a popularizing one.”

Perhaps the burden is on you to interrogate that, since “popularizing” is an easy and vacuous dismissal until you explain the ways the work suffered from an appeal to popular taste.

“How can you read Spiegelman saying, “I have no idea — pocupines?” and not be certain that he thinks he’s the smartest guy in the room?”

He can’t make a joke?

“Well, then he can’t win, can he?”

Art is hard, especially when you’re tackling such a charged and difficult subject. You “win” by being intelligent and thoughtful. Setting yourself up so you can make all the punchlines and look like the smart guy; I’m sorry, that doesn’t impress me.

And a Maus arranged to let Spiegelman get the better of everyone he encounters would be very different.

The porcupines remark does a couple of things: it points out the limits of the visual scheme and is a subtle jab at the use of the Holocaust to justify aggression, a detail I’m glad is in there now that the book is a fixture on required reading lists. Notice, also, the aggressive demeanor of the journalist who asks the question- mouse-masked and an obvious representative for Israel, in counterpoint to the hostile German reporter. I don’t see how representing Israelis as aggressive and prickly “glibly ties into ugly Zionist narratives positioning Israeli aggression as righteous defense.”

It’s difficult to imagine how Spiegelman could have portrayed his misgivings over the book’s success without providing fodder for this kind of treatment. You write at length about the masks:

“…because they are drawn in profile, where we can see the mask-strings, the reporters comes across as macabre and deceptive… Artie is drawn mostly looking out at the reader; you can’t really see the mask… the contrast between their clear masks and his “natural” features shows clearly who has the right to speak…”

But how could Spiegelman have staged the meeting to show the masks equally? The only way would be to show every character in profile, a very flat composition. He could have shown his head from the back while the reporters confront him, but then see how this kind of treatment can be applied to any choice the artist makes:

“Spiegelman privileges himself by emphasizing his humanity behind the mask while the reporters, although masked themselves, are concealed between the dehumanizing images. See how Spiegelman manipulates the reader to feel besieged and take his side…”

As it is, Spiegelman opens the scene with an image of himself wearing the central visual conceit of the book as a false face, shows himself engaged in its production on the backs of the murdered, and regressing to infancy in response to a barrage of both friendly and hostile questioning. On the other hand, he does tell a joke about porcupines.

It’s not that hard to imagine. As I said, he could have looked at the ways in which he’d enabled it.

And as for how Spiegelman could have staged the scene…at this point you’re basically arguing that art is just so hard that we can’t actually expect artist’s to think about their choices and make something meaningful. There are lots of ways he could have dealt with that scene, or,you know, lots of ways he could have written a scene that doesn’t suck. This is supposed to be one of the masterpieces of the comics form; one of the medium’s great works of genius, but I can’t expect him to pay attention to what he’s doing with the visuals? If you set the bar any lower, you’d have to start digging.

The porcupine is a jab at using the Holocaust to justify aggression? In what world? Presenting Israel as an animal that is dangerous to pick on and defends itself passively is not in any way a critique of or questioning of zionism. For pity’s sake.

“As I said, he could have looked at the ways in which he’d enabled it.”

Drawing atop a mound of corpses and saying he wants absolution doesn’t do that? And I’m waiting for your discussion of his “popularizing”.

“The porcupine is a jab at using the Holocaust to justify aggression? In what world? Presenting Israel as an animal that is dangerous to pick on and defends itself passively is not in any way a critique of or questioning of zionism. For pity’s sake.”

As I said, notice the hostile, belligerent demeanor of the Israeli reporter who asks the question, and Art’s panicked reaction. (And what’s going on with the character’s puffed chest in his first panel and distended stomach in the second- who is he, Ariel Sharon?) So Israel is represented as both hyper-defensive and aggressive.

I think we’re just going back and forth at this point. I’m happy to agree to disagree.

I think artie’s interest in the “low” is as genuine as his interest in the “high” and has been evident nearly his entire career. However, that doesn’t preclude him from being a snob, which he most certainly is. His use of “pulp” or “junk” modes always rubs me the wrong way, like he’s sitting with all his friends at a “sophisticated” dinner party praising each other for hiring such good “help”.

I really don’t know what’s worse, someone of inherent class, culture and privilege appropriating junk, or someone poor and self-educated being pretentious… okay, actually, the latter is far preferable now that I think about it.

Tarantino as mentioned is an interesting comparison. Tarantino’s work is more and more filled with big issues, but actually seems to be getting more childish… or at least he’s doing all he can to resist. Or, maybe he’s being entirely serious and thinks he’s saying something profound? I think he’s somewhere in the middle, I guess. I’d definitely rather watch any Tarantino film than read any more of artie’s “work”.

There are a lot of genre or exploitation treatments of the Holocaust/WW2/Any Atrocity that I find more interesting (and not just formally) than artie and stevie’s middlebrow takes: the above mentioned Man in the high Castle, Munk’s Passenger, Hogan’s Heroes, Night Porter, In a Glass Cage, etc. None of these are necessarily as good or as responsible as night and Fog or The Destruction of the European Jews, but not everything needs to be, even with a subject as heavy as the Holocaust.

Certainly Maus (and artie’s whole career) remains an eminent example of hubris, presumption and entitlement in a field of study where those characteristics are unfortunately commonplace and undeserved.

But hey, at least he’s not Ted Rall.

Pingback: Tempest In A Peepot | A Trout In The Milk