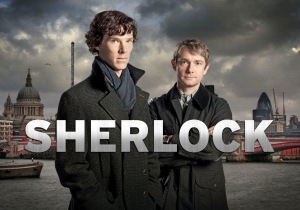

Emily Bazelon likes superheroes. Her New York Times Magazine article “The Online Avengers” chronicles the adventures of Anonymous hackers who use their powers to combat cyber-bullying. Bazelon says Anons tend to think in “polarized terms,” viewing their cases as “parables with an innocent victim, evil perpetrators and ineffectual (or corrupt) law enforcement,” all staples of the superhero genre. But Bazelon enjoys some of those polarized terms too, describing how her aliased Avengers “team up” or “join forces” to expose “wrongdoers.” She draw one activist in origin story rhetoric: “He vowed that day he would do something about Rehtaeh Parsons’s death.”In Bazelon’s defense, the rhetorical infection seems to originate with the Anons she interviews. “We wanted to strike fear into their hearts,” declares one Batman wannabe. They even wear Guy Fawkes masks from Alan Moore’s V for Vendetta.

But it’s the wrong metaphor. These aren’t caped crusaders patrolling the mean streets of Gotham. The streets are Facebook and Tumblr. The superpowers are laptop-based. Many of the crimes—posting a video on YouTube or a message on Twitter—take place in the no man’s land of the world wide web. The bad guys can live anywhere on earth, but they elude justice by exploiting a virtual frontier.

What we have here is a Western.

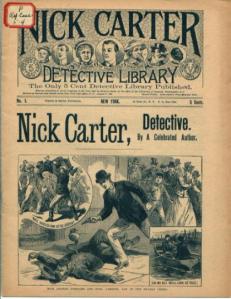

Owen Wister largely invented the genre when he published The Virginian in 1902. His bad guys disappear into the mountain sanctuaries of Wyoming: “He that took another man’s possessions, or he that took another man’s life, could always run here if the law or popular justice were too hot at his heels. Steep ranges and forests walled him in from the world on all four sides, almost without a break; and every entrance lay through intricate solitudes.”

When journalist Amanda Hess dialed 911 after receiving death and rape threats via Twitter, the Palm Spring cop who arrived at her door dismissed them because the “guy could be sitting in a basement in Nebraska for all we know.” The bad guy was safe in the intricate solitudes of his IP address. Hess documents her experience, and dozens like it, in her recent Pacific Standard essay “Why Women Aren’t Welcome on the Internet.” When Caroline Criado-Perez received similar threats after petitioning the British government to include women on its currency, she retweeted them until the international attention forced police to respond. They said it was Twitter’s problem. Twitter said threatened users should contact local authorities.

Wister’s Wyoming faces the same failure of law enforcement. Because “the law has been letting our cattle-thieves go,” a former judge declares: “We are in a very bad way, and we are trying to make that way a little better until civilization can reach us. At present we lie beyond its pale. The courts . . . into whose hands we have put the law, are not dealing the law. They are withered hands, or rather they are imitation hands made for show, with no life in them, no grip. They cannot hold a cattle-thief.”

But Bazelon’s Avengers are skilled at tracking cattle-thieves’ user IDs through walled websites and forests of social media. When four teens in Texas tweeted gang rape threats at a twelve-year-old in New Zealand, the team of Anons unmasked their Twitter handles and forwarded evidence to the boys’ highs school administrators. The Virginian’s punches are “sledge-hammer blows of justice.”OpAntiBully settles for screenshots.

When Rehtaeh Parsons’s mother received evidence of her daughter’s rape, she turned it over to OpJustice4Rehtaeh, an Anonymous group she originally distrusted as nameless vigilantes. But, she told Bazelon, “if pressure from this group is what it takes, let them do what they do.”

Wister’s judge reasons similarly: “And so when your ordinary citizen sees this, and sees that he has placed justice in a dead hand, he must take justice back into his own hands where it was once at the beginning of all things. Call this primitive, if you will. But so far from being a DEFIANCE of the law, it is an ASSERTION of it—the fundamental assertion of self governing men, upon whom our whole social fabric is based.”

Local authorities tend to disagree. When badgered into reopening a rape case by OpMaryville and Justice4Daisy, the sheriff of Maryville, Missouri complained: “They all need to get jobs and quit living with their parents.” Parsons’s alleged rapists—or at least the two who posted the YouTube video of the crime—are now facing child pornography charges, though a police spokesman warned that OpJustice4Rehtaeh could come under investigation too.

Meanwhile, Cattle-thieves have their own advocates. Hess reports that the Electronic Frontier Foundation—a free speech and privacy rights group—lobbied against the Violence Against Women Act because an amendment to the act updated phone harassment to include any electronic communication. When Hess started receiving threatening voicemails on her own cell phone and police still refused to make a report, she took the law out of their withered hands. She tracked the guy’s IP address, filed a civil protection order, hired a private investigator to serve court papers, and got a judge to approve a restraining order that included everything from Twitter to hot air balloon messaging.

Which is to say Hess is no vigilante.

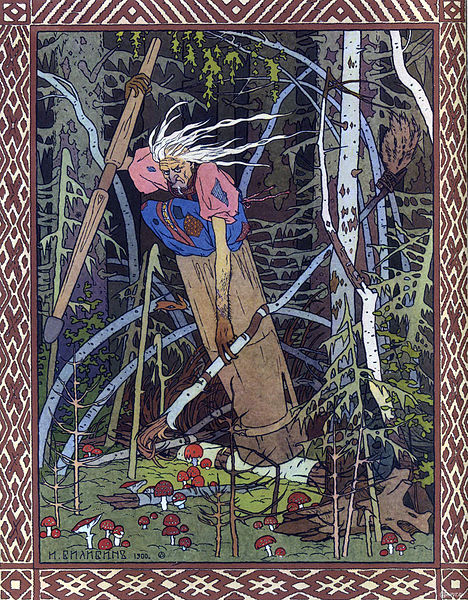

When the Virginian catches horse-thieves, he lynches them. That means Wister and his judge have to spend a lot of their frontier rhetoric differentiating this private but supposedly law-and-orderly form of capital punishment from the “semi-barbarous” lynching and burning of “Southern negroes in public.” Apparently the swift hanging of “our criminals” puts no “hideous disgrace upon the United State.”The judge doesn’t quibble over the definition of a “criminal” though, since the term denotes someone who has been legally tried and convicted, a luxury Wister’s frontiersmen forgo.

The Virginian ends his adventures when his once-skeptical love interest accepts his system of retribution and marries him. By the end of Bazelon’s article, her lead Avenger has lost his girlfriend of nine years—she complained he never turned off his laptop at night. Hess mentions a boyfriend but would rather write about the “Frontier of Female Sexuality” and “the gun-toting, boob-grabbing douchebags who are subsidizing your online porn habit.” She’d also like to see internet harassment prosecuted as a Civil Rights issue, a wonderfully civilized aspiration far beyond the pale of the current U.S. legal system.

In the meantime we’re left with faceless superhero wannabes trying to make our virtual frontier better until civilization can reach us.