This post is the first in a series on how comics artists represent talk in comics. I’ll be writing about speech balloons and how the discipline of conversation analysis (CA) helps us understand how creative these artists can be when they try to show the intricacies of everyday talk.

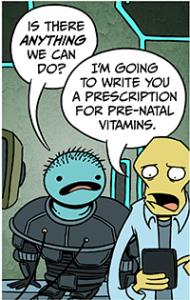

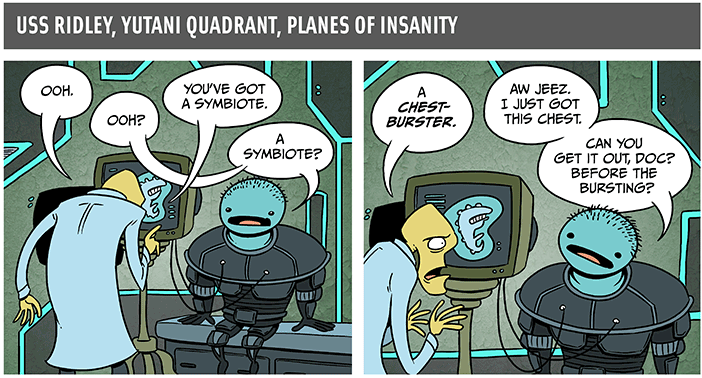

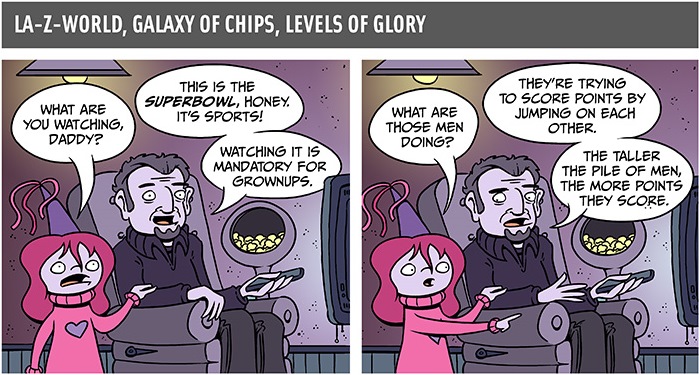

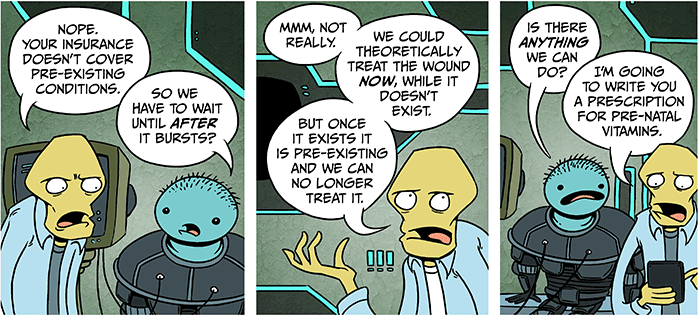

Consider the following two panels. These are from the webcomic Scenes from a Multiverse by Jon Rosenberg. (Click on each of the titles to see the full comic.)

| The Symbiote (February 1, 2013) |

The Superbowl (sic) (February 4, 2013) |

Both of these are the final panel in the comic. Specifically, each one is panel 5 of a 5 panel comic. Understanding the speech and the speech balloons in these two panels will depend on the sequencing of balloons in previous panels and, to some extent, the social context of the conversation.

In most kinds of comics, speech balloons show conversations in relatively uncontroversial ways. In smaller panels, there may be one, two, or three characters producing speech, while larger panels and full-page panels may contain a dozen or more characters talking at the same time. In conversation analysis (CA), the approach to studying talk is to keep track of the number of turns, how long the turns are, how many speakers there are, and how much silence there is, among others. This post is the first in a series about speech balloons and conversation sequence. In particular, I will focus on how comics artists draw two or more characters talking at the same time.

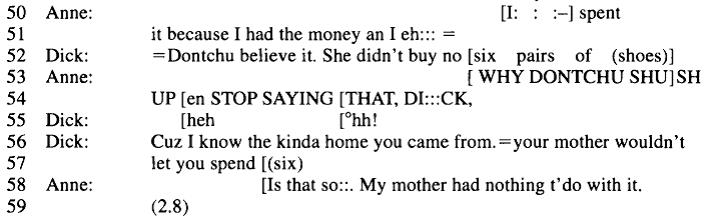

When two or more speakers produce speech at exactly the same time, then this is called simultaneous talk. (Sometimes it is called interruption, and sometimes it is overlap, but this depends on interpretation.) When listening to conversations, it is relatively easy to identify moments when participants are talking ‘on top of each other.’ And in transcribing the speech, there is a small set of typographical symbols that scholars typically use to do this. Consider the following excerpt, taken from an article by Emanuel Schegloff (2000) on simultaneous talk (p. 26). The two speakers, Anne and Dick, are an elderly couple who have been married for a long time. In this short excerpt, we see a good bit of simultaneous talk. Anne and Dick are having a conversation with their daughter, and it takes a funny turn in that Dick gives Anne a hard time about spending money on shoes and her claim about how many pairs of shoes she owned.

SOURCE: Schegloff, E. (2000). Overlapping talk and the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language in Society, 29 (1): 1–63.

Lines 52 and 53 are clear examples. According to this transcription, at exactly the same time that Dick begins the word ‘six,’ Anne begins her utterance with ‘WHY’. The effect is that while Dick already has the conversational floor, Anne joins in, and the listeners have to keep track of what both of them are saying. At the end of Dick’s word ‘shoes’, he stops speaking but Anne continues her turn through line 54. The use of all capital letters indicates that Anne is using a LOUD volume.

It’s one thing to listen to speech and write it down in a transcription. But in comics, it seems to me that it’s a creative challenge to represent simultaneous speech using speech balloons. In other words, how does an artist use visual cues (putting one balloon on top of another) to signal a certain kind of verbal cue (two or more speakers talking at the same time)?

The question I have is whether the visual difference in the balloons has a material impact on the way readers ‘hear’ the speech. Does the doctor’s turn ‘sound the same’ as the dad’s turn? If there is a difference, is it a difference of kind or a difference of degree? To answer the questions, we should examine each of the comics in terms of conversation and speech balloons.

The Symbiote

The first two panels of ‘The Symbiote’ show very traditional strategies for representing turns and turn-taking. The doctor in panel 1 begins the sequence, with the patient taking the second turn, and the two trading off in panel 2 as well. Even though the tails cross in panel 1, I think readers would perceive these turns as more or less separate, perhaps with no simultaneous speech at all. In panel 2, the visual separation of the balloons is even clearer, indicating that the two speakers are being careful to take turns without ‘stepping on each other’s toes.’

The Superbowl (sic)

In panels 1 and 2 of ‘The Superbowl,’ the speech turns proceed much like those in ‘The Symbiote.’ I think the visual separation of speech turns here is crisp, with the tails of the balloons never crossing. The content of the balloons indicates that the daughter takes the first turn by asking a question and the dad takes the second turn by answering the question. This is true for both panels.

If we consider the sequence of panels 3-4-5 in both comics, we may be able to discern more readily whether the speech in the final panels are indeed different kinds of simultaneous speech.

| The Symbiote | ||

| Panel 3 | Panel 4 | Panel 5 |

| The Superbowl | ||

| Panel 3 | Panel 4 | Panel 5 |

In both comics, panel three is composed very similarly. The speech balloons of speakers 1 and 2 are touching, and in fact the balloon of speaker 2 is ever so slightly overlaid onto the balloon of speaker 1. Panel 4 in ‘The Symbiote’ has just one speaker, the doctor, but Panel 4 in ‘The Superbowl’ shows the two speakers producing some measure of simultaneous talk.

As we saw at the beginning of this post, panel 5 for both comics shows that one balloon is overlaid on top of the other. It is more than likely that readers are supposed to ‘hear’ simultaneous talk. In other words, the doctor talks at the same time as the patient, and the dad talks at the same time as the daughter.

What interests me about them is that in both panels, one speech balloon overlaps the other. There are some slight differences, however. In ‘The Symbiote,’ the doctor’s speech balloon overlaps the patient’s speech balloon, but all the words are visible. On the other hand, in ‘The Superbowl,’ the dad’s balloon overlaps the daughter’s but also partially obscures two words (on and grass). What is not clear is whether the balloon obscures additional words or other symbols in the balloon, symbols like ellipses (…). But is the amount of simultaneous talk the same? If we hear the panels differently, what elements of each comic are we meant to consider when we decide how they sound?

When you read these two comics, how do you ‘hear’ the turns playing out? What might Rosenberg be trying to accomplish by drawing one speech balloon on top of another? How much does the turn-taking sequence affect our perception of the balloons? And how much of an impact does the social context or the identity of the speakers have?

In part 2 of this series, I’ll talk about simultaneous discourse in Grant Morrison’s The Invisibles.

Nice job! I’d like to see you take on the elaborate, intertwined speech balloons in most Brian Michael Bendis comics: I’m not sure it’s simultaneous speech often, but it’s still a way to visualize rapid interchange.

I love overlapping speech bubbles, because they suggest a reading rhythm.

When I read comics, the extent of the overlap to me suggests to what extent one person is talking over another. In the first case above, I’d read that as the doctor ‘jumping in,’ but not talking over. Maybe the last word was spoken over, if at all.

In the second case, the father talks over a substantial part of the daughter’s speech.

I’d be interested in how this plays out in terms of the writer, artist and letterer collaborating to present the conversation.

Oh, and a couple of years ago a wrote a piece for Sounding Out! about sound in comics and argued (in part) that our familiarity with the rhythms of conversation help provide the inter-panel closure that make comics work.

“This is Not a Sound”: The Treachery of Sound in Comic Books

Hi, Corey! Thanks! I’m not familiar with Bendis, but I will put those comics on my reading list.

Kailyn, I think you’re right. It seems that the dad more actively ‘cuts off’ what the daughter is saying.

Thanks for the link, Osvaldo. I will check it out!

If you haven’t already, I recommend that you take a look at Howard Chaykin’s American Flagg!

I find the final panel of the Super Bowl sequence particularly fascinating (and by the way Frank – I suspect that you are one of a minority of academics who would have caught the mistake in “Superbowl”!)

I like to think about the content of comics panels on roughly Waltonian terms, as some of you know (see Kendall Walton: Mimesis as Make Believe: On the Foundations of the Representational Arts, Harvard 1993). So the question I like to ask is: What are we meant to imagine when ‘decoding’ the panel and its contents?

Now, consider the partially obscured word “grass” in the last panel, and the undepicted but somewhat strongly implied final word “for” in the same panel. There are at least six questions we can ask:

(i) Are we meant to imagine that the daughter utters “grass”?

(ii) Are we meant to imagine that the father hears the utterance of “grass”?

(iii) Are we meant to imagine that we hear the utterance of “grass”?

(iv) Are we meant to imagine that the daughter utters “for”?

(v) Are we meant to imagine that the father hears the utterance of “for”?

(vi) Are we meant to imagine that we hear the utterance of “for”?

The best answers I have to these questions are (i) Yes – definitely (ii) Maybe? (iii) Yes – I think, (iv) Maybe – It might be another word (although that seems unlikely) (v) No – I think, and (vi) I have no freaking idea.

I would love to hear what others think about this.

Conversation analysis seems like a very fruitful way of looking at speech balloons and turn-taking in comics, Frank. This post is quite helpful. Though I, too, am given pause by the obscured aspects of the daughter’s speech in Panel 5 of The Superbowl, I am even more intrigued by the difference between the overlaps between father and daughter’s speech in panels 4 and 5. I tend to be most interested in issues of power when I look at transcribed conversations (who interrupts whom? who speaks longer, who asks more questions, who adds tag questions like “right?”, “isn’t it?,” etc., how do the speech patterns displayed echo or refute relative degrees of speaker status, how is silence used….). Therefore, I’m struck by the fact that the daughter’s balloon overlaps her father’s in panel 4 (as it logically should since her question came first in time), but the father’s balloon overlaps the daughter’s in panel 5 despite the fact that her question must have emerged prior to his admonishment. In the case of panel 5, the performative act of the father– hushing his daughter–trumps strict narrative time, and we get to see that his desire to watch the commercials blots out/cancels his previous patience with his daughter’s questions and thus, covers over/blots out her linguistic agency. I’d definitely say this proves your point that speech balloons can be used creatively to make the reader imagine speakers conversing in a natural way, but also to indicate the perlocutionary aspects of these speech acts.

Roy! I knew I needed to acknowledge the spelling of Superbowl, if for no other reason than the comic is a satiric comment on the way that Americans engage with that particular pastime.

As I was writing the post, I was imagining how you might bring Walton to bear on it. Your questions i-vi are great, and it’s fun to think about them. I’ll respond a little more to them below.

Adrielle: thanks for a great comment…I find CA to be an important and useful tool in understanding language in comics. In my own research, I also try to ask questions about social identity and power as they are found in conversation, and I’m glad you mention them. I chose these two comics because there is a kind of parallel here: we might call both of them examples of asymmetrical discourse because one speaker (the doctor, the father) has more social power than the other speaker (patient, daughter). The relationships aren’t the same, of course, but they offer a productive opportunity for comparison.

I think that Roy’s questions ii & v relate very specifically to Adrielle’s questions about power and agency. Perhaps the father hears the daughter’s turn in its entirety but simply chooses to ignore it. In this case, though, the content of the dad’s turn (Quiet sweetie…) suggests that even if he does hear the whole turn, he is actively squashing it. (This is also a weird example of language socialization, when caregivers use linguistic strategies to teach children how to behave.)

I think panel 4 in The Superbowl is a problematic moment of speech balloons and simultaneous talk gone awry, and I am thinking about coming back to that one in a future post.

Hi, Tony. I will add Chaykin’s American Flagg to my list, too. Thanks for the note.

Love this post, Frank! I also want to echo Adrielle’s comments (and your response) about how the overlapping speech balloons visualize the dynamics of power and agency in the conversation really well. What struck me at the end of “Symbiote” is more than just the fact that the two are talking over one another, but that they are no longer even engaged in a genuine conversation. Once the doctor shifts into the jargon of health insurance protocols, he is basically just talking to himself. As a result, the overlapping balloons convey a greater distance between the two speakers, and although the doctor is in the position of authority, his unwillingness to listen makes him look foolish. The same is true for the second strip, where the father’s ignorance about the sport prompts him to leave the conversation by shifting into condescending “parent-speak.” Is there are term/concept in linguistics for when speakers have mentally left a conversation and their speech goes on a kind of autopilot of trite phrases and meaningless responses?

Thanks, Qiana! (I had fun writing it!)

When describing that moment when a speaker goes on ‘autopilot,’ the term that comes to mind immediately is ‘conversation routine.’ When we say things because we’re supposed to say them, we’re frequently using a routine.

Robert Hopper wrote about routines, and one example that always struck me was the telephone conversation. We start out by saying ‘hello’ or some equivalent. But really that isn’t even the first turn. The first thing that happens is that the phone rings, so it’s a signal that we need to enter into a routine to begin the conversation successfully.

Routines are only a small part of our repertoire, though. We use those formulaic utterances to greet people, to say goodbye, to open or close committee meetings, etc. So I wouldn’t say that the dad is using a widely used routine. On the other hand, you termed it “condescending ‘parent-speak,'” and my best guess is that there are formulaic utterances that parents use with their children quite regularly.

I’m afraid that I don’t have a good answer for the other part of your question, when speakers have mentally left a conversation. I think that’s a much harder question!