At the ‘old’ Pencilpanelpage location I began my contribution to our reign of comic scholar awesomeness with three posts about when distinct versions of a comic are, or are not, really the same comic in the relevant aesthetic/interpretational/etc. sense (see When Are Two Comics the Same Comic Part I, Part II, and Part III, which focus on rearrangement of panels, recoloring, and redrawing ‘lost’ portions of old comics, respectively). Those posts focused on issues having to do with ontology – determining whether or not we have one work of art, or many – with an eye towards how these issues affect our reception of, and overall assessment of, these comics (and comics like them) as works of narrative art. This post is a continuation, of sorts, to that investigation.

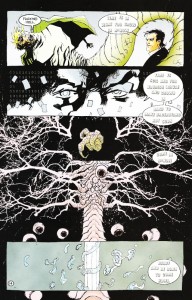

Here, however, I would like to take a slightly different approach to the general question, but one which is motivated by the same phenomenon: multiple, aesthetically distinct versions of the same comic. The instance in question is well-known – Issue #2 of The Invisibles Volume 3, “The Moment of the Blitz” (which is actually the 11th, and second-to-last, issue in this volume – the numbering counts down from 12 to 1). In the original comic, pages 12 – 14 are drawn by Ashley Wood. These (especially page 14) are critical pages, summing up major metaphysical themes underlying The Invisibles in little more than a dozen panels. In the tradepaperback collection, however, Ashley Wood’s pages are jettisoned in favor of a re-drawing of this critical passage by Cameron Stewart, who had also drawn a number of pages of this issue in the original floppy version. I have included scans of the critical page 14 here – first the Wood version, then the Stewart version.

Here, however, I would like to take a slightly different approach to the general question, but one which is motivated by the same phenomenon: multiple, aesthetically distinct versions of the same comic. The instance in question is well-known – Issue #2 of The Invisibles Volume 3, “The Moment of the Blitz” (which is actually the 11th, and second-to-last, issue in this volume – the numbering counts down from 12 to 1). In the original comic, pages 12 – 14 are drawn by Ashley Wood. These (especially page 14) are critical pages, summing up major metaphysical themes underlying The Invisibles in little more than a dozen panels. In the tradepaperback collection, however, Ashley Wood’s pages are jettisoned in favor of a re-drawing of this critical passage by Cameron Stewart, who had also drawn a number of pages of this issue in the original floppy version. I have included scans of the critical page 14 here – first the Wood version, then the Stewart version.

Now, the reason the pages were redrawn is simple enough, and well-known: Morrison felt that Wood had not properly captured his ideas on the page, and Stewart was asked to ‘do it right’ for the trade paperback version. Patrick Meaney described the Stewart pages as follows:

Cameron Stewart deserves credit for redrawing pages originally illustrated by Ashley Wood for the trade paperback version. Those original pages can be quite confusing, obscuring thematic points that Morrison had been building toward throughout the series (Our Sentence is Up: Seeing Grant Morrison’s The Invisibles, 2011, p. 250)

and an entry on comicvine.com described the situation as follows:

The Cameron Stewart pages are considered the true version since they were redone for the Trade. Ashley Wood’s pages are interesting because they were a different interpretation of the same script.

These sorts of descriptions, however, pose a serious issue for comic scholars (and for anyone who wants to understand how comics work as an art form, and anyone who thinks such an understanding might enrich our experiences with structurally rich comics like The Invisibles). Comics scholars like to talk about comics (at least, mainstream comics, as opposed to single-creator auteur works) as a medium of genuine collaboration – the thought is that the distinct artistic visions of writer and artist ‘blend’ somehow into something greater than the sum of the invididual contributions. Regardless of how, exactly, the details of this work, the central idea – that comics are a collaboration between writer and artist (and perhaps others) is almost a truism of work on comics, if anything is.

These sorts of descriptions, however, pose a serious issue for comic scholars (and for anyone who wants to understand how comics work as an art form, and anyone who thinks such an understanding might enrich our experiences with structurally rich comics like The Invisibles). Comics scholars like to talk about comics (at least, mainstream comics, as opposed to single-creator auteur works) as a medium of genuine collaboration – the thought is that the distinct artistic visions of writer and artist ‘blend’ somehow into something greater than the sum of the invididual contributions. Regardless of how, exactly, the details of this work, the central idea – that comics are a collaboration between writer and artist (and perhaps others) is almost a truism of work on comics, if anything is.

The redrawn pages of The Invisibles Volume 3, however, suggest that comics is not a collaborative endeavor – at least, it isn’t a collaboration between two creators whose endeavors are equally valued and whose endeavors contribute equally to the identity of the work. Instead, the picture we obtain from this incident is that artists are merely journeymen (or journeywomen) of a sort who toil away in service to someone else’s artistic vision (and whose work can be thrown away, and replaced by the work of another, if it does not fit that vision).

In short: There seem to be two accounts regarding how writer-artist interaction might (and more importantly, should) be viewed. On the first account, writers and artists are equal collaborators on a single artistic work whose final characteristics are determined in roughly equal part by each. The second account of writer-artist interaction is suggested by the use of the word ‘interpretation’ in the quote from comicvine.com. This view has it that the artist is not an equal collaborator, but is instead interpreting the writer’s story (in much the same way that a performing musician might interpret a piece of composed music). Note that we would not usually call a performer interpreting a composed piece of music an instance of collaboration!

Now, on the one hand this seems to be merely a question of how the business of comics works, and in this particular case it is not surprising that a creator of Morrison’s caliber would be allowed so much control over ‘his’ work (the scarequotes are very important, since the appropriateness of this term, rather than ‘their’, is exactly what is at issue). But there are also deep theoretical issues lurking hereabouts – ones deeply connected to the title of this post. If Morrison and Stewart (and hence Morrison and Wood) are genuine collaborators, then replacing Wood’s pages with Stewart’s amounts to replacing one collaborative work with another one entirely. If, however, Stewart and Wood are not creators of the artwork, but are merely interpreters of it, then the situation amounts to replacing one interpretation of the work with another interpretation of that same work.

So the question really is this: Do we have two distinct works here, or merely two different interpretations of a single work of art? Or, alternatively, are artists more like composers, or more like performers interpreting composed music?

My comment is not about the two pages themselves, but I was immediately struck by the similarity of the cover of that Invisibles issue to the cover of Lois McMaster Bujold’s SF novel Komarr, which came out just a year earlier (and was the latest of a series of similar “face-off” covers on her Vorkosigan novels).

The thought that immediately strikes me is that in his desire to have the pages redrawn, Morrison is acting as a form of author-editor (or writer/director to use film). As such, yes the the degree of authority over the work and the amount of credits leans in his direction. Furthermore, since the series was written throughout by one writer, but drawn by different artists, it makes sense to me to consider it “Morrison’s work” with the input of various collaborators whose contribution is mitigated by the writer (and/or editor).

I am not sure if I find your questions that useful in thinking about this. I do think this instance does point out the degree to which artist contribution to these kinds of comics is skewed as to favor the writer. I guess the writer can be seen as a form of writer/director as in film, while the artist is some form of cinematographer. Actually, I hate film analogies for comics, but I am just struggling for language to describe the range of working relationships.

Here is a question for those who know more about studying film than I do (which should be a lot of people ;) – How do film scholars handle different cuts of the same film? I don’t mean remakes, I mean “director’s cuts,” substantial re-mastering, etc. . . Is is possible that the answers to Roy’s questions can be found in looking at that as a guide?

As it’s currently displaying, the Stewart page is first and the Wood is second. (I’ve only seen the remake since I’ve just got the trade version.)

I asked Corey Creekmur on facebook; this is what he had to say:

Aaron: You’re right – I have fixed this!

Osvaldo (and Noah and Corey): I think it is important to distinguish between two questions: Are there different versions that (justifiably) receive distinct critical attention, and are there genuinely two artworks here.

The former question, as Corey points out, should be answered in the affirmative (and this is, if not common, then at least not all that rare in film). But the musical analogy was meant to bring out that this doesn’t necessarily mean that there are two distinct artworks – different interpretations of musical works might be assessed and evaluated differently even though we might want to say that there is still just one work of art (and two interpretations of it), not two.

(Like Osvaldo, I am wary of drawing analogies too tightly between different art forms, whether comics, film, or music, but sometimes with a new field like comic studies that’s all we have to start with!)

I also suspect that, if we are careful, cases like this are more common in comics than we think. To be more careful: there certainly aren’t that many cases where different versions of comics DO receive distinct critical attention. But there are certainly a large number of cases where, were we attentive to the differences, we might be motivated (and might be justified in doing so) to treat different versions differently.

In addition to the other sorts of examples discussed in the three posts that preceeded this one, a sort of example that I am thinking about a great deal right now is cover art. In trade paperbacks usually all but one of the covers from the original floppies are reprinted as if they were just additional pages of the comics (i.e. as part of the interior art, rather than as the cover). Although we don’t have anything like a well-worked out account of how cover art works, and how it affects our interpretation of interior art, it seems likely that the new role that covers are playing in trade paperbacks might warrant attention in this regard.

I have another example in this category– webcomic artists who go back and redraw sections of their comic. Using the music analogy, it’s the same interpreter of the same script, but these are still different interpretations.

I’m drawn to the idea that the works are completely different, but I know it doesn’t really hold true to experience. The mind automatically categorizes them as the same thing– they share more than they depart from, and a lot of the material that ‘matters,’ (plot, text, characters, the other 20 some pages,) are identical.

But didn’t even switching around the images above change the reading experience of this essay? I prefer Stewart’s page, although I’m intrigued by Wood’s. When Stewart’s was posted first, I thought it was Wood’s, and it contributed to my understanding of the narrative of “Poor Ashley!– what the hell is this thing replacing it? That’s an eccentric choice.” Now, I feel like Morrison’s decision makes much more sense– Morrison corrected the comic to make it look more stylistically conventional, mainstream even. For me, the nuance of the piece, and the point I thought you were making, changed.

The sheer intentionality of comics drawing impresses me. Little is really captured by accident– and just by its being drawn, a detail adds to a comic’s meaning. So, I feel like a close reading of both of these comics could dig up completely, completely different meanings– and they’d be different works.

Also, did Grant Morrison give any visual direction in his scripts, like, at all?

I thought in comic fandom circles that there’s a separate distinction- between the initial artist who does the character designs (and is sort of the prime mover of the visual look of the book) and the artist who just one of many subsequent people who work on the book?

A number of DC comics for example, will created the people who “created” the character- including the original artist- and it seems to be suggesting the original artist is in more sense a “creator” while the later ones are more likely to be considered “journeymen”?

Pallas: I don’t think things can be quite that simple (although it might be the case that fandom treats things as if they were this simple).

Other than the famous case of DC drawing over the Superman faces Kirby drew in Jimmy Olsen, I think subsequent artists often do add to or change the look of established characters, often in rather significant ways. Just think about all the different visual interpretations of Wolverine since Byrne (it was Byrne, wasn’t it?) drew him.

This raises additional questions about what ‘counts’ as the definitive version of a story: What does Wolverine look like? Does his appearance vary from story to story? Is it all just stylistic variation (except, presumably, for the first artist who drew the character)? Hard questions – I recently wrote an article (not yet published) on exactly this topic!

” I think subsequent artists often do add to or change the look of established characters, often in rather significant ways. – ”

Sure, but once a character “catches on” who writes or draws it doesn’t so much matter, or at least, pretty much anyone at Marvel and DC is completely expendable and their absence would have no significant impact on the viability of the characters or the company in the long term.

It’s only if you trace back to the original creators who created a “winning” character that you can really say “If not for that artist… this popular book would not exist.”

Now Wolverine might be a little more complicated, since he didn’t catch on as a popular character in his first appearance. But as a general principle the flourish freelancer #895 brings to Spider-man is really not all that significant compared to Steve Ditko.

Roy, this is a great continuation of your series.

I think that in this case, it’s one comic with two different versions. A couple of pages were changed out, which for me doesn’t change the whole comic. To make this choice, I went back to your Part II on The Killing Joke. In that case (if I remember correctly), the whole comic was recolored. And my opinion then was that the recoloring had a significant impact on the meaning of the comic because it affected the whole thing. It isn’t clear that the substition of a portion of a comic has the same kind of impact. Were any of the other pages changed? Or only the Wood/Stewart substition?

Some months ago, Noah posted an essay about cross-over interpretations of music. (http://www.salon.com/2013/11/30/the_19_best_cross_genre_covers_of_all_time/) When Tori Amos covers ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ by Nirvana, is it the same song or just a different interpretation of it?

I think the comparison you make to music composition and performance sheds a lot of light on the subject.

Kailyn, I have seen Morrison scripts, I think, and there are visual directions, but they weren’t especially clear (I think Moore gives much more precise directions…and of course Stan Lee didn’t really give directions at all. Or that’s my understanding anyway.)

One of my first posts here at HU was about how art in Morrison comics is often a mess: https://www.hoodedutilitarian.com/2007/09/grant-morrison-transcendence-and-shitty-art/

With music covers at least the Borges story about Pierre Menard seems like it’s relevant….

“Do we have two distinct works here, or merely two different interpretations of a single work of art?”

You already answered that question in your second paragraph, to wit — “the same phenomenon: multiple, aesthetically distinct versions of the same comic.”

In general, it seems super-odd to imply that there are deep ontological facts of the matter about artwork-identity, rather than sociological-cum-psychological facts about how we choose to talk about artworks (where those choices are determined by pragmatic factors, context, etc). What on earth could possibly make it true that one comic really is (or, if you prefer, Really Is) the same as another one?

In any case, even if we accept that there are weighty metaphysical questions at stake, it’s not prima facie obvious to me that we should accept these two conditionals:

“If Morrison and Stewart (and hence Morrison and Wood) are genuine collaborators, then replacing Wood’s pages with Stewart’s amounts to replacing one collaborative work with another one entirely. If, however, Stewart and Wood are not creators of the artwork, but are merely interpreters of it, then the situation amounts to replacing one interpretation of the work with another interpretation of that same work.”

Does the question of collaboration/ownership really determine the question of identity in that way? Couldn’t those two questions come apart?

(BTW, don’t take this comment the wrong way — I’m 100% for this kind of philosophical approach to comics!)

Jones,

I am actually sympathetic to the idea that the deep ontological facts are determined (at least in large part) by sociological and psychological (and physical) facts about the various practices of production and reception for a particular art form. But that doesn’t mean that these facts aren’t real (or Real, as you put it), after all, speed limits are determined by social conventions, but there is still a real fact of the matter regarding how fast one can legally drive on my street.

At any rate, the way that these practices determine the ontological facts might vary from art form to art form, so it can be dangerous to generalize too much from one medium or form to another (not saying you were doing so – just pointing this out – and of course my own comparisons to music run just this risk!) Further, the metaphysical facts (or proper appreciation of them) might in turn have a sort of ‘feedback’, affecting practices of production and reception in turn.

And of course, since comics studies is so new (relatively speaking) we are probably barely scratching the surface of the complexities involved in this sort of case.

Also, I think you might have read more into the conditionals than I intended: I didn’t mean to imply that the direction of determination necessarily flows in that direction – on the contrary, I am tempted to think that it is the practices that have become conventional within the world of comics’ production, consumption, interpretation, and evaluation that determine whether we have two distinct artworks, or rather merely two interpretations of a single artwork, and that this in turn determines whether Morrison and Stewart are collaborators, or the latter is merely producing an interpretation of the former’s work.

(Of course, all of this is complicated by the fact that often an interpretation of an existing work can be a work of art in and of itself – think of jazz standards, and various improvisational interpretations of them. The latter are arguably both interpretations of the former work and individual art works in and of themselves!)

Frank: You might be right – replacing 3 pages in a trade paper-back sized work (or in the whole series of volumes, depending on how one wants to individuate ‘the work’) is a minor change in one sense. But it isn’t so minor in another. One of the reasons that the pages were changed is that they (especially the last, which is the one I reproduced) are central to understanding the metaphysics of The Invisibles. So although the page count of the change is small, the overall impact of the change on our interpretation and evaluation of the work might be rather significant. I am just not sure here.

Oh, and Jones: I won’t take comments like these the wrong way. Professional philosophy is a rather aggressive academic discipline (for better or worse), so I am both used to, and 100% in favor of, people challenging my ideas and proposing alternative views!

One last comment: I didn’t mean to imply in any of the above that artists are ‘interpreting’ Morrison’s story in the same sense as performers might interpret a musical piece or a theater troupe might interpret a work of Shakespeare. It was meant merely as a possibly illuminating analogy. The reason why I feel this disclaimer is necessary is that taking the ‘interpretation’ talk too literally here might push us towards the unfathomably popular idea that comics are in some literal sense a kind of performance – an idea that I find completely absurd.

“might push us towards the unfathomably popular idea that comics are in some literal sense a kind of performance – an idea that I find completely absurd.”

Why is that absurd? All art has performative aspects, at the least, it seems like…?

Roy — “right on” to all that.

Noah,

We need to be careful about what we mean here. Comics can certainly be ‘performative’ in some respects (although I find that particular term very vague in a way that prevents it from doing much philosophical heavy lifting) in the same way that comics can be ‘cinematic’ or ‘literary’. But all this implies, at best, is that comics have some features in common with performance art forms (or with literature and film, in the cases of ‘literary’ and ‘cinematic’ comics). And this in turn explains why the application of pre-existing theoretical frameworks and tools from literature studies, cinema studies, etc., have been so fruitful in the early days of comics studies. Of course, we can explain all this quite easily by noting that comics are a hybrid art form, which inherited some of its characteristics from the media that serve as its historical ancestry (e.g. literature), and by noting that it has much in common with other hybrid forms that share some of this ancestry (e.g. film). Aaron Meskin briefly discusses this in his paper on comics as literature.

All of this shouldn’t fool us into thinking that comics are a form of performance, any more than it should fool us into thinking that comics are a form of literature or a form of cinema (see my “Why Comics are Not Films” in my anthology for more on this). Of course, the idea that comics are a form of literature is even more common than the claim that comics are a form of performance (and I don’t know anyone who has claimed comics are film, although McCloud claims that film is a weird form of comics at one point).

Adopting a view where comics is just a special case of another pre-existing, well-studied medium tempts us into thinking that all the tools and perspectives we need to understand comics will already be found in the work on that other, supposedly overarching art form. And this, I think, is a mistake (that is the real point of “Why Comics are Not Film”). Meskin makes a similar point about comics and literature in his paper on this subject – while they have much in common since comics is a hybrid form, comics also have many characteristics that are distinct from the standard features of literature, and assuming that comics are literature obscures the issue and encourages us to ignore these differences.

With regard to performance, I just think there are too many differences between the standard features of performance art forms (improvisation; audience reaction, and sometimes participation; spatial and temporal location, etc.) and comics to take the claim seriously. That being said, however, it is clear that thinking about how comics are LIKE performance – that is, those aspects of comics that might be similar to standard features of various types of performance – might be a fruitful exercise.