Bill Waterson’s Calvin and Hobbes is a strip about the wonders of imagination. And, as this famous Sunday shows, the wonder there, and the imagination as well, is insistently self-referential. The opening white space of the page is a nod to the white space of the page, so that the page represents the moment before creation just as the moment before creation turns around and represents the page. The calligraphy foregrounds the artist’s hand, even in the usually ignored realm of lettering, while the close-up of the eye-of-Calvin winks at Watterson’s own eye, gazing down upon the page. Calvin’s virtuoso acts of creation, the planets he sets spinning, are, at the same time, Watterson’s virtuoso acts of creation. That hand, from which a galaxy forms, points to Watterson’s actual hand, from which the galaxy forms. “He’s creating whole worlds over there!” Calvin’s dad enthuses, by which he means Calvin, but which could also, and does also apply to Waterson himself. The mom’s response, “I’ll bet he grows up to be an architect,” is ironic because Calvin’s imagined creation/destruction of the universe is figured as gleefully asocial rather than as a career path. But it’s also ironic simply because she’s got the wrong profession. Calvin is training to be an artist/cartoonist, not an architect; his future is, literally and figuratively, Watterson’s present. The comic can be read not as a winking laugh at the distance between child/adult perceptions, but as a kind of smug moment of gloating; Watterson/Calvin is cooler than his parents and cooler than architects. He’s a gloating god who gets paid not just for the creation, but for the gloating.

The strip’s celebration of imagination is predicated on the link between Calvin and Watterson. But that link is itself created through careful separations; to make Calvin and the cartoonist parallel, certain lines can’t meet. Thus, here, as throughout Calvin & Hobbes, the barrier between imagination and reality is carefully maintained. Calvin’s imagination is rendered in a more detailed, more expressionist style, again, even the text is written in calligraphy; reality, on the other hand, is drawn in Watterson’s standard cartoony format. The child’s-eye world and the parent’s eye world are visually and conceptually distinct. The wonder of Calvin’s imagination, and of Watterson’s, is figured specifically as a wonder by making clear that it is set off from the normal and everyday. Hobbes the tiger is a marvelous creation because the purity of the creation is underlined by Hobbes the stuffed animal. In order to celebrate childhood and (Calvin or Watterson’s) creativity, you need a nothing, a blank, to stick it in and compare it to.

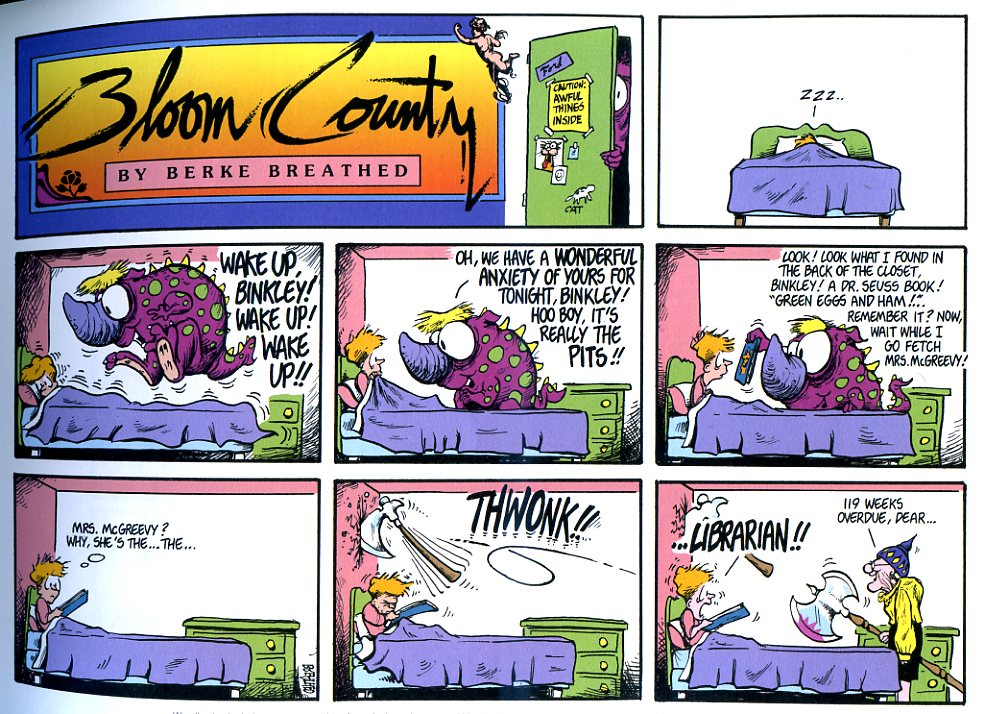

Bloom County’s treatment of imagination and of childhood works quite differently. This strip, for example, does not start with blank space, to be filled with creativity. Rather, it starts with Binkley being woken up by a Giant Purple Snorklewacker — you come out of dream to be in a dream. The one panel with no fantastic elements is not at the end — as ironic reassertion of the real — but in the middle, as a kind of pause or beat between absurdities. Nor is there a stylistic indication of what’s real and what isn’t. The Snorklewacker’s shock of unruly hair looks much like Binkley’s shock of unruly hair; Mrs. McGreevy looks like any other pleasantly dumpy Breathed old person except for that ax.

The imaginative content here is also less virtuoso riff than fuddy-duddy pratfall. In fact, the narrative seems designed to conflate the joy of childhood with the banal worries/fantasies of adults, so that “Green Eggs and Ham” becomes an occasion not for gleeful rhyming, but for worrying about due dates.

Nor is it just childhood fantasies that are punctured; in his notes to this cartoon in the Bloom County library reissue, Breathed notes that the strip was inspired by discovering his own out-of-date library book — a Frazetta art book. Mrs. McGreevy in Viking helmet can be seen, then, as a parody of Frazetta’s barbarians, and also as a kind of back-handed (back-axed?) comment on Breathed’s own imagination, or lack thereof. Give me a noble warrior, Breathed says, and I will turn it into a librarian and a neurosis. Breathed may be the Snorklewacker, gleefully leaping up and down in anticipation of tormenting his character, but he’s also that character, Binkley, who worries the way adults worry. The line between adult/child gets is smudged over, just like the line between fantasy and reality.

You could argue that these smudgings — the fact that the Snorklewacker occasionally escapes into the real world while Hobbes never does, or the fact that Calvin is always a six-year-old with a six-year-olds interests, while Binkley has anxious daydreams about economists — means that Calvin and Hobbes is the more true-to-life strip. I tend to agree with Bert Stabler, though, when he argues that Bloom County is in the mode of realism — especially when we use Ambrose Bierce’s definition of realism as “the art of depicting nature as it is seen by toads.” Calvin and Hobbes revels in creativity; Bloom County deflates it. Watterson creates a world from nothing; Berkeley Breathed insists that your flights of fancy will be fined.

Inevitably, Watterson’s self-vaunting optimism in the power of childhood and comics is the popular and critical darling, while Breathed’s dumpy skepticism is either ignored or forgotten. But for me, at least, I much prefer Breathed’s sly, exuberant pfft to Watterson’s rote magic. Certainly, I’d happily trade all of Watterson’s cosmic shenanigan’s for that single motion line Breathed uses to show the curlicue path of the ax, so you have to imagine the head flipping around before embedding itself in the wall. Or, for that matter, for that first picture of the happy Snorklewacker leaping up and down on the bed, a scrunched purple bundle filling the room almost up to the ceiling with jittery motion lines, imagination not as expansive power, but claustrophobic vibration.

Bloom County is realistic, I’d argue, not because it eschews fantasy, but because it doesn’t. In Breathed’s world, the real and the ridiculous crowd in on one another, elbowing each other for space in the same low-ceilinged room. Children are not proto-artists to be glorified, but just schlubs like the rest of us, beset in equal measure by the snorklewackers in their own brains and by the due dates in everyone else’s. The artist isn’t a god, but a horny toad, who provides, not wonder, but nagging, and an occasional ax.

_____

The entire Bloom County roundtable is here.

Those are great strips to compare, if I’m allowed (in my childish fantasy) to examine them as stories about fascism. A force that destroys in calligraphic glory in one, a librarian dressed as a Hun in the other. Which one are we actually afraid of? Calvin, as you note, is ultimately nonthreatening because, mainly, he’s sympathetic (and a boisterous blonde lad at that). The neurotic, socially iffy Binkley, on the other hand, is threatened, and his dream is left unframed as the psychological reality of his world.

That’s an interesting point. I’d say Calvin is also not really scary as god because it’s all framed as cute; we laugh at him pretending he can hurt us, or anyone. The joke is actually that he’s harmless. Whereas with the Bloom County strip, you’re laughing not necessarily because the librarian is harmless, but because anxieties do feel like that. The joke is that the anxiety is real, rather than that the fantasy isn’t.

I’ve never read Bloom County so I can’t speak to how it fines our flights of fantasy, but could you argue Watterson consistently deflates fantasy as well? Calvin is always trying to get away with something or imagine an existence more suitable to himself and the world (or his own imagination via Hobbes) smacks him down. Calvin is not training to be a cartoonist but not trying or training to be anything at all – an ultimately futile undertaking as the world is constantly pushing him to be something. If he does reflect Watterson himself, then it is a sad sort of reflection. That’s the joke half the time. I think people might read it today as justifying or glorifying the imagination, but I know I read it growing up as a quite dark take on the desperate futility of the imagination. Calvin’s boxed-in fantasy will one day become adult anxiety. Those lines he draws between the imagination and reality strike me as a highly skeptical response to those who believe the imagination can somehow transcend or blur those lines. Maybe that’s my own reading though. Interesting conversation.

Yeah; I’ve seen people read the strip as a depressing take on neurosis; Calvin living in creepy fantasy world, etc.

I don’t exactly buy it. This strip seems like a pretty good counterargument. The link between Calvin and Watterson is very strong (white page as nothingness; creating world and then destroying it.) And the strip is so much about Watterson’s technical virtuosity in general, it’s hard to see imagination as depressive or sad in that context (as opposed to Peanuts, where the virtuosity is much more muted and inward turning.) I don’t think there’s much sign that Calvin will eventually be anxious or neurotic; he’s a bad boy troublemaker for the most part, not a sad sack like Charlie Brown.

I think there is nostalgia for childhood, which shades into sadness or longing. But I don’t see a lot of actual anxiety in this creation cartoon, or in Watterson’s work in general.

I think to say Calvin & Hobbes is one thing or another is to not give it enough credit. It slides along a continuum from strip to strip and sometimes within a single strip from nostalgic for childhood play to critical of the isolating possibilities of imagination, from Hobbes being the best buddy in the world (my imaginary stuff toy BFF) to being a pin to deflate childhood ego (or maybe the adult ego that imagines childhood as this solely wonderful and free time).

I do think think that nostalgia for the strip itself has transformed it into this kind of pollyanna take on the wonders of childhood, which sucks.

As for Bloom County, it has been a long time since I have read it – but I think the above strip is a great mash-up of childhood anxiety put into a form adults can digest. However,the anxiety it concerns itself with (an overdue library book) is a fairly superficial one in comparison to what many kids have to worry about, which kind of makes the anxiety itself into a joke through what is precipitating it. Which is fine. I get it. Our minds get stuck on stupid shit sometimes.

In the strip from yesterday’s post with the economists, there is the opposite problem – wherein Binkley’s anxiety is solidly adult frustration with the incoherence of the world of economies and politics, so in the framing device (monsters in the closet) evoking childhood, it suggests that the feeling of lack of control can make us feel like children again. I think that’s okay, because either way the monster thing is just a device Breathed uses in various ways, but it is a rather obvious device for whatever kind of anxieties he thinks of without much of a pattern to them. Breather makes Binkley as grown up or as kid-like as he needs him to be for his joke from strip to strip.

Yeah; I like the way that the kids world and the adult world aren’t separated clearly. Watterson’s much more careful about that. I prefer the mess.

“Calvin is training to be an artist/cartoonist, not an architect; his future is, literally and figuratively, Watterson’s present. The comic can be read not as a winking laugh at the distance between child/adult perceptions, but as a kind of smug moment of gloating; Watterson/Calvin is cooler than his parents and cooler than architects.”

I’ve never gotten the sense that we’re intended to infer that Calvin will grow up to be a cartoonist like Watterson himself. As for what “can” be read as “smug gloating”, all that’s required is the mindset to see it; that’s not the same as evidence that this is a correct reading.

The dithering of economists is banal, rendered absurd by Binkley’s horror, just as overdue library book is banal, rendered absurd by a barbarian librarian, just as trains running on time is banal, rendered absurd by appeals to the glory of blood and soil. All of the imagination play in Calvin and Hobbes is played for idealized creative mischief, a la Dennis the Menace (perhaps its closest analogue, also a beautifully-rendered romance of white male childhood). When the imaginary play of Bloom County characters is portrayed, the message does not seem to be “look at what this little genius does with a stuffed tiger and a baseball and snow,” but rather “this elaborate and somewhat violent fantasy is transparently foolish.”

Well, art isn’t an algorithm. I provided a reading in which I believe the smugness and the gloating seem fairly clear. You can always provide a different reading.

I don’t think Calvin is usually seen as growing up into a cartoonist. I think his imagination and Waterson’s are often placed in parallel, though, and I think that this strip’s insistence on the question of what Calvin will grow up to be ends up pointing to an answer.

Yeah; it’s not about sadness or depression. It’s about banality. C&H may be sad or happy in its gracefulness, but it’s always graceful. Not Bloom County.

Screw perfect art, is basically my message here.

On that note, a quote from Durkheim and Mauss on the difference between clean and dirty flags:

“The definition of the holy as what is set apart, whole and complete, one and physically perfect, explains why there is horror in burning or cutting the flag, and danger in its being dismembered and rendered partial. A worn and tattered flag is ritually perilous and must be ceremonially burned so that nothing at all is left. The flag is treated both as a live being and as the sacred embodiment of a dead one. Horror at burning the flag is a ritual response to the prohibition against killing the totem.”

Noah got to it before I did, but Bloom County border between childhood and adulthood is much shakier than in Calvin and Hobbes, and scanning last Sunday’s funny page on the kitchen table next to me, most comics out there. Most comics seem to mine a lot of humor out of ‘adult vs children,’ and the occasional ‘Look at this man child.’ Similarly, the animals and people do not verbally communicate with each other. Bloom County occurs in this weird abstracted realm where social norms still float around, but the power hierarchies that supported them have broken down.

Berke Breathed I think often talks about not knowing much about cartooning when he started. There’s definitely a sense in which he doesn’t quite understand the rules.

He definitely had something to say, though. For all the media platforms nowadays, it does seem to be as hard as ever to be a sort of klunky one-person operation and get any kind of wide audience.

It is annoying that Hobbes is always a stuffed tiger and there’s no real ambiguity there. Contrast Snoopy, whose status is completely variable and whose imagination intrudes dramatically into the so-called “real” kids world so much that all boundaries are erased. Still, I like C & H and Bloom County. I don’t think we have to choose.

Isn’t the most obvious comparison of BC to Doonesbury? Didn’t people accuse Breathed of stealing Trudeau’s style? Maybe I’m misremembering. BC is goofier, I guess, but it definitely has quite a bit of Doonesbury in it.

I’m not so sure the line is that clear in C&H, I don’t have specific examples but there are strips where it would be hard to explain events without Calvin’s imagination bleeding into the real world, even if everything always looks mundane from the adult perspective.

I think it’s pretty clear. If you can find a strip where it isn’t I’d be pretty surprised.

For instance, the sequence where Calvin makes duplicates of himself. At some points, it seems like he couldn’t possibly be all those places at once. But then it’s rationalized with his mother saying, “he just seems like he’s everywhere today!” which is the sort of thing parents say about kids.

Everything’s like that. Hobbes isn’t even allowed to be a real tiger with Suzy, who narratively is willing to interact with him like he’s real. The rules are quite strict, and Watterson never violates them. Or at least, I’ve never seen him violate them, and I’ve read a fair bit of C&H (maybe all the books? Not sure though.)

Maybe I just wished there was more ambiguity. It’s true that Hobbes is unfailingly stuffed when Calvin isn’t alone.

Eric,

BC did copy/riff on a lot of Doonesbury, including the style and the character Limekiller. Breathed is very transparent about this in his commentary in the most recent BC collection.

“I like the way that the kids world and the adult world aren’t separated clearly. Watterson’s much more careful about that. I prefer the mess.”

Peanuts is often compared to Calvin and Hobbes, but, going by your description, it may be closer to Bloom County.

Here’s a suggested topic for your roundtable: what was the source of Breathed’s decline? I haven’t seen that much Outland or Opus, but my impression is that they both got carried away with themes that were also present in Bloom County when it was pretty good. Outland seemed to be filled with sickly-sweet whimsy, and I remember Opus as focusing a lot on grotesque “ugly American” characters.

I read somewhere that he quit Bloom County because the deadlines were killing him. The story was that, instead of mailing his strips in to the syndicate, he’d often deliver them in person so that he could finish drawing on the plane flight.

I’ve read all of the Bloom County collections and a lot of the Calvin and Hobbes strips, and although it’s been awhile since I read these, the impression that I came away with was that with Bloom County there was this illusion of a sense of community among the characters, whereas with Calvin and Hobbes it was more like delving into someone’s private world. All of the topical humor and the characters based on media personalities (I’m remembering a Joan Jett-like rock star character), plus the longer story arcs-it seems like Breathed was concerned with the outside world and wanted his characters to interact with it, whereas Watterson mostly shuts it out; I might be wrong, but I don’t remember Calvin having any friends (I remember a little girl character, but it seemed like she wasn’t really a friend of his), a lot of strips were about snow days when the power goes out and there’s no school and society generally breaks down, etc. Thinking about the recent overrated musician topic, I would say Bloom County is to Calvin and Hobbes as the Beatles are to the Beach Boys-the first is extroverted and inclusive, while the second is introverted and (sort of) exclusive. I like them both, but they speak to different moods and emotions. I’d also say that with Bloom County it worked better when I read whole collections, they gained momentum as the strips progressed, but with Calvin and Hobbes I found it difficult to read too many strips at once, too suffocating. I do enjoy particular C&H strips better than some Bloom County stories, though (I like Watterson’s art better, plus his humor I think has a little more rhythmic variety than what Breathed offers).

Calvin’s relationship with Suzy is somewhat complicated. I wouldn’t say they weren’t friends exactly, though.

The Beatles/Beach Boys comparison is interesting. My problem with Calvin as introverted melancholy genius is that it’s just a bit too easy going down. Brian Wilson’s pretty explicitly about banality in a funny/frightening way (Busy Doin’ Nothin’ comes to mind.) The celebration of imagination in C&H makes for a very full world, even if it’s tinged with melancholy at times.

Calvin’s not terribly likeable much of the time. Sympathetic perhaps, but kind of a jerk too. Interesting to me that none of the “tributes” such as Frazz or that fanfic-ish Hobbes and Bacon thing (http://imgur.com/tUzAL) quite seems to get that, focussing (it seems) only on the magic and whimsy of the strip and putting aside its frequently bitter tone.

I love Calvin & Hobbes, but I agree it’s overrated — its brilliance is in its execution, not the core concept. Watterson is such a good artist, he makes Calvin’s Walter Mitty-esque fantasies come beautifully to life. I bought the first volume immediately when I found it in a bookstore, before it was running in local papers.

The main problem with C&H is that it never develops or changes. Watterson’s art improves a teeny-tiny bit, but Watterson basically does the same trick over and over and over. There’s no story-esque continuity within Calvin’s world, and no major shifts in tone or style over the course of the series. It’s perfect as a day-by-day strip, but it just gets dull in large quantities. Watterson clearly knew what he wanted to do from the very beginning and he did it well, but the most interesting comics, to me, are ones that wander all over the map, or at least where we can see the artist’s progress.

Osvaldo is right again, this time regarding C&H. It was a pretty accurate representation of childhood, with all the wonder, fear, frustration, and helplessness. But as with real childhood, many people only remember the wonder, because that’s what they choose to reflect on.

On the dual nature of Hobbes, here’s what Watterson said in the C & H Tenth Anniversary Book: “The so-called ‘gimmick’ of the strip — the two versions of Hobbes — is sometimes misunderstood. I don’t think of Hobbes as a doll that miraculously comes to life when Calvin is around. Neither do I think of Hobbes as the product of Calvin’s imagination. The nature of Hobbes’ reality doesn’t interest me, and each story goes out of its way to avoid resolving the issue. Calvin sees Hobbes one way, and everyone else sees Hobbes another way….I think that’s how life works….Hobbes is more about the subjective nature of reality than about dolls coming to life.”

It’s a fact that many of the stories involving supposed figments of Calvin’s imagination — Hobbes, duplicate Calvins, deranged mutant killer snow fiends, what have you — are easier to follow from Calvin’s point of view and even difficult to explain without accepting some of the fantasy. That’s why his parents are sometimes perplexed by evidence that doesn’t add up. That may mean that some of what Calvin “imagines” is real, or it may mean that Occam’s razor is a poor guide to truth. The simplest explanation often has nothing to do with what’s really happening.