Earlier this week, Brannon Costello suggested (with a hat tip to Walter Benjamin) that fascism could be seen “as the aestheticization of political life, the process by which a state-sponsored fantasy of heroic struggle overwrites and replaces real social, economic, and political anxieties.”

Earlier this week, Brannon Costello suggested (with a hat tip to Walter Benjamin) that fascism could be seen “as the aestheticization of political life, the process by which a state-sponsored fantasy of heroic struggle overwrites and replaces real social, economic, and political anxieties.”

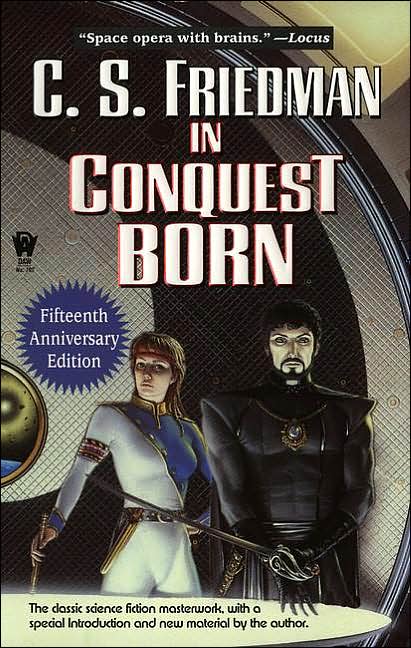

I was thinking about this definition in terms of C.S. Friedman’s novel “In Conquest Born.” The book is sci-fi space opera, but it functions in a lot of ways as a super-hero narrative. The main character, Zatar, is a Braxin, a warlike culture of distant human descendents who have been genetically manipulated to be superstrong and supertough. Zatar is strong and tough and cunning even by the strong, tough, cunning standards of Braxia, and much of the book is a series of vignettes designed to show just how damn awesome he is. He infiltrates the enemy Azeans and poisons a key figure; he goes on a one-person space ship and withstands high gravity pressures in a way no one has withstood high gravity pressure before, he machinates sneaky spy plots causing the death of his enemies, he wows women and has his way with them. He commits ultra-cool sneaky awesome genocide. And so forth.

Again, this fits pretty easily into superhero tropes — and/or supervillain tropes to the extent that they can be distinguished. What’s interesting, though, is that the superhero fascist undertones — the way in which aesthetics replaces politics — are here made thoroughly explicit. Braxia is fascist state. As I said, it’s a warrior empire; it just about worships war and battle. It’s organized along racial lines, too: the rulers (the Braxia) are a small minority of genetically enhanced humans. The regime is hyperbolically masculine; rape of women is legalized, and rule or subservience to women is seen as terrifying and evil.

The novel doesn’t exactly endorse the Braxian view of the world — it’s supposed to be a brutal, ugly culture. But that brutality and ugliness are in themselves an aesthetic attraction; a venue the main purpose of which is to set off Zatar’s charismatic brutality and ruthlessness all the more vividly, and therefore all the more sexily. There’s a sense in which the entire nasty race, complete with legalized rape and endless warfare, is there just so we can watch various brutal, hard warlike men and women fall to their knees (often literally) before Zatar’s bigger, badder warlike bits. The political/social trappings of a fascist state are all channeled into the aesthetic pleasure of the Mary Sue.

Zatar isn’t the only Mary Sue in “In Conquest Born.” Friedman has another; Zatar’s sworn enemy, Anzha, a member of the Azeans, a culture locked in an unending war with the Braxins. Anzha is a powerful telepath, and the part of the book that is not devoted to showcasing Zatar’s awesomeness is devoted to showcasing Anzha’s. The capstone of ridiculousness here is when Anzha, more or less at random, has to cross an ice planet and succeeds by telepathically bonding with intelligent extraterrestrial superwolves. “In Conquest Born” is from the 1980s, before fan-fic really took off, but that just shows that the tropes are of long-standing. And yes, after she succeeds, people kneel down to her too.

But despite that kneeling, Azea is a very different society from Braxin. It’s not a warrior culture. Women are equal to men. It arrives at decisions through a not-super-well-defined-but-still democratic process. It’s remarkably racially heterogeneous as well; the Anzha empire is based on equality, and many alien peoples are equal members. The society isn’t perfect by any means; Anzha faces discrimination because she doesn’t physically fit the genetic human Azea pattern, and the telepathic bureaucratic secret organization screws with her brain in unpleasant ways without her consent. But still, in its broad outlines and ideology, Anzha pursues a liberal policy of peace and inclusion, rather than a fascist policy of war and purity. Anzha, with her telepathy and her fierce love of war and killing all things Braxin (because Zatar poisoned her parents) could be seen as a Superman figure, a liberal, battling, anti-fascist fascist.

Siegel and Shuster didn’t monkey around with relativism; Superman may have been a kind of doppelganger of the Aryan Ubermensch, but that wasn’t meant to create an equivalent. Good was good, bad was bad; and if one was the mirror of the other, that emphasized the differences, not the similarities.

Friedman is less partisan. Ultimately, I think Anzha is supposed to be the force for good, not least because she wins in the end. But, again, the two characters work in almost exactly the same way — they’re both dark, heroic, angsty totems performing awesomeness in repetitive set pieces. Zatar replaces the fascist political system with the aesthetic iconicity of his coolness; Anzha replaces the liberal political system with the aesthetic iconicity of her coolness. And not just the political systems themselves, but the conflict between them, is turned into an individual matter of style, as Zatar and Anzha are enmeshed in a personal grudge feud/telepathic love thingee, which shakes the stars and keeps the pages turning, if you like that sort of thing.

You could see this as exposing the definition of fascism that we’re working with here as self-contradictory. Aestheticization of politics means that aesthetics overwrites politics — in which case the content of the politics doesn’t really matter. Fascism, liberalism — who cares? As long as you’ve got your anti-heroes, it’s trivial whether they run with wolves or commit genocide. It’s all the same marginally entertaining genre fiction, and it doesn’t need to mean anything more than that.

From a bleaker perspective, though, you could argue that the banality of the genre fiction, the emptiness of its political content, is a sign not of the irrelevance of fascism, but of its ubiquity as a kind of substrate in both mass culture and modernity. Those dreams of strong warriors to whom everyone kneels; they’re as native to Azea as to Braxin, it seems like. Victory of one over the other is a satisfying denoument, not for any ethical or political reason, but simply because the strong looks stronger when he, or she, subjugates the strong.If modernity overwrites all political systems with aesthetics, then fascism isn’t just one possible political system of our day, but the blueprint for them all.

Not being snide, have you read any genre fiction without fascist undertones?

Sure; romance novels don’t have much to do with fascism, I don’t think. (They do have something to do with patriarchy, but I don’t think those two things are interchangeable.)

Also, “fascist undertones” suggests that the books subconsciously support fascism, which isn’t always what’s happening, I don’t think.

Ahah, forgot that there are other genres than SF for a moment. I certainly don’t think romance or even many crime novels have much to do with fascism. But one sometimes wonders about fantasy and sci-fi, even when written by self-awoved socialists.

I’d reckon that any genre of literature or art that engages modernity and notions of scientific progress will engage fascism, as fascism is so bound up with modernity. If a body of literature escapes this, it’s probably because it is engaging with with premodern or postmodern conceptions of subjectivity.

It’s funny, I’ve had trouble engaging this conversation because fascism has ceased to be the devil term it once was in academia. Now, it’s always about neoliberalism.

Yeah, what is it with neoliberalism? If there’s some aestheticized anaesthetic banality of evil empire out there, that’s neo-it nowadays. Yeesh. And superheroes have had something of a return-of-the-repressed renaissance this century. If corporations are people. why can’t they be superpeople? No Hannah Arendt blaming the bureaucracy any more, everyone’s a contractor or a robot. No Walter Benjamin bemoaning false consciousness– consciousness is dead, long live hypercognition.

What about westerns? Does the story of the hero that rides in and saves the day have fascist undertones? It seems like a lot of the superhero tropes apply. And does it matter whether it’s a lone rider western or a communal action ensemble piece?

Chris Gavaler was just writing about links between superheroes and westerns….and Alex Buchet wrote about it as well.

Bleh. Frankly I think that’s a really dopey and shallow mis-definition of “fascism”.

This definition may have some connection with the films of Leni Riefenstal. But what does it really have to do with any other aspect of fascism? Not a whole lot.

The more I’ve studied actual historical fascism, the more I think this sort of trite lit-crit treatment of fascism is just *inaccurate*. Fascism is NOT the same as authoritarianism. Fascism has a lot of much more specific characteristics, mostly relating to economic policy.

It is partly about a giant show — diverting all complaints about problems to targeted scapegoats — but that’s not unique to fascism either, nor is it key to fascism.

A lot of these tropes you talk about are way, way pre-fascist.

Fascism has crucial *economic system* characteristics which aren’t covered here. Part of the promise of fascism is that all those supporters of the state, who are in the preferred class, WILL get fed, clothed, etc., and the fascist state will provide them with wealth, power, etc. — and this will be done within a modern industrial society.

It’s quite possible to have all the political abusive nastiness while having a system which doesn’t promise supporters anything, or which only promises things to those few who provide personal loyalty.

Zatar — for example — is no different from the Greek Herakles, or any number of other extremely unappealing myths from the ancient world, including too many to count which are in the Bible. This isn’t fascist. It’s pre-modern.

Personal charisma *is* politics in the pre-modern, as well as in the fascist.

Most fantasy and space opera makes intense attempts to be pre-modern. The complete failure of the writers to understand modern economics usually results in a pre-modern authoritarian result. If the writer actually uses modern economics (very very rare) then you might get a fascist result.