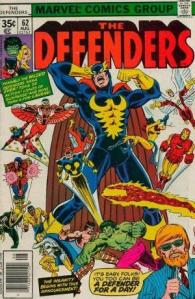

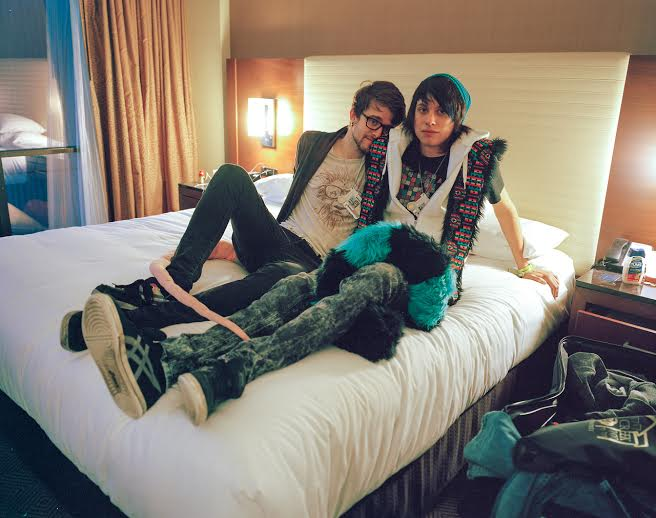

Tommy Bruce / Fursuiter Group Photo, Midwest Furfest, Chicago, IL 2013

Tommy Bruce is a senior at the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore, intending to graduate with a BFA in Photography and a Minor in Creative Writing in the Spring of 2014. He was born in Boalsburg, PA and grew up in State College, PA, running around the backyards of Penn State. I met Tommy Bruce at Furry Weekend Atlanta 2011. I was struck immediately with his exuberance and enthusiasm for his project to document the Furry Fandom, and we became friends. I’d like to share a conversation about his work and experience with Furry so far.

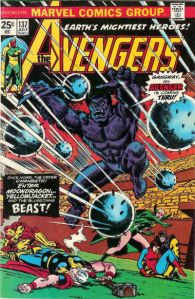

Tommy Bruce / Jasper, Midwest Furfest, Chicago IL, 2012

Michael Arthur: Can you remember the first time you heard about furries? Was it from the internet or other media?

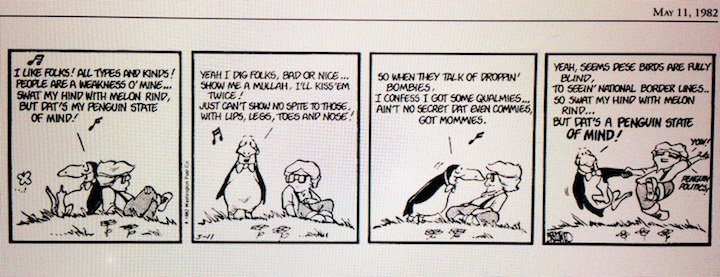

Tommy Bruce: There are a couple memories from around my sophomore year in high school, which is I guess about seven years ago now, that are kind of simultaneous. At that time, I was playing a lot of World of Warcraft, surfing 4Chan, and listening to videogame podcasts. Those weren’t the only things I was doing with my life… I had friends… But those are the places I heard furries being mentioned. I remember lots of jokes about Sonic the Hedgehog fans just being crazy furries, and remember lots of “fursecution” jokes on (4Chan Subforum) /b/. I have a distinct memory of looking through some image collection of memes and then smack in the middle was a drawing of a rabbit character with giant boobs and a huge package. That is for some reason a clear memory??? I knew furries were the butt of jokes and it was weird to be one. I guess those are my first memories.

MA: Can you recall a media profile so far that portrays the furry fandom with satisfactory accuracy? Or one that has resonated with you personally?

TB: Does the episode of Check it Out with Steve Brule Count?

MA: Yes, that counts.

TB: There is a podcast called “irregular podcast” that did a decent job, I remember. There are a few podcasts that have done a good job though, I’m recalling your spot on Drawn this Way. On TV though, or in video documentary online, there isn’t much I can think of that does a very good job. Most have been too far one-way. They either completely ridicule furries as a bunch of childish adults or perverts or really, as failures. Or the piece takes on a super apologetic and defensive stance that tries to tell all about “what furries aren’t”. Those ones are nearly always written by furries and don’t get seen by many people.

Tommy Bruce / Ataraxia and Spiral-Staircase, Midwest Furfest, Chicago, IL 2012

Why I liked the episode of Check It Out is that John C. Reiley’s character is strange enough that the two fursuiters were allowed to be normal. The humor wasn’t relying on making furries a laughing stock, so much as it was making a joke out of bad television, which is the premise of that show in general. So in that move, furry culture was put as just another part of society, if that makes sense. What’s tough about TV media is that there isn’t much good education on anymore, it’s only really good for written work, like 30 Rock or Portlandia, or Breaking Bad. Most people don’t get news from TV, and most documentary style shows have gone the route of “reality TV” which is distinctly different from reality, and really doesn’t follow any of the basic rules of documentary work.

MA: I’m intersted in your role as simultaneous documenter and participant, since I feel like I share a nearly equivalent degree of distance and immersion in my own experience of furry.

TB: mmhmm :)

MA: what is the role of your education and training in your interaction? More specifically, from your fine art’s perspective, does Furry’s status as a “low culture” affect your perception of it, or your participation in it?

Tommy Bruce / Fursuit Football Gear Photoshoot, Midwest Furfest, Chicago, IL 2013

TB: It definitely has affected my perception of what is important for me to see, and what is interesting to me when I’m interacting with the fandom. There are a lot of sectors in furry culture that probably wouldn’t interest me on a personal level. Similarly, I meet a lot of furries who I don’t have much in common with, but I still enjoy getting to know them because I like seeing different facets of the community. It does get somewhat confusing when reflecting on my own desire to participate though. I have spent countless hours in my mind trying to justify learning a dance routine to perform in fursuit. Like “well maybe I can make this into some performance piece for the gallery.” I still haven’t given up on that one. That line is definitely in my mind though, because as an artist I want to make something that is contributing to a conversation. With my work about furry culture, I want to try to test the limits of documentary work.

I’m a participant, and struggling with my own insecurities and needs as one. But I’m trying to be as transparent about that as possible. At the same time, I’m trying to explain this cultural phenomenon as it happens. I think asserting a clearly subjective, but informed POV can be interesting. I’m not the first to do this. David Foster-Wallace’s “A supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again” or James Agee’s “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men” are big forerunners for what I want to do; Nan Goldin and Larry Clark too, in terms of photographers. But there is still some room in that conversation to be explored, so that’s where I’m trying to pick up.

MA: Being a participant in good faith affords you access that I don’t think any journalist can ever get. You have your subject’s trust when furries at large are very cynical toward media attention.

Tommy Bruce / Tails Neck Tattoo, Furbowl 44, Wilmington, DE, 2013

TB: Most definitely, I’m finding that more and more as the years go.

MA: You’ve had access as a documentarian to corners of furry that I, as a furry journalist haven’t, like babyfur room parties.

TB: And more ;)

MA: AND MORE!

TB: Because of some subjects current desire to stay anonymous, I can’t exactly specify with whom and when, but yes, more. I’ve photographed a few modified fursuits, had a couple people pose sexy for me, slapped a friends balls on his request at a wild furry new years party… Whether any of those photos will see the light of day anytime soon is yet to be determined. But if I can’t use any of those photos, I’m determined to find subjects who are comfortable talking about this aspect of the furry community. I’m trying to build an environment to view my work where the viewer is beyond shock value. I want to help viewers to empathize with my subjects. The work, to me, is about how people go to great lengths to connect with others and to feel satisfied with their life, and in doing so create a beautiful and intricate and interesting culture. It’s more about how that is a beautiful and overarching quality of mankind, not about how some group of people took a wrong turn in their lives and ended up here.

MA: Reporters still seem to have a hard time getting past that.

TB: the shock value?

Tommy Bruce / Barkley and Flip kissing at Midnight, New Years Furry Ball, 2014

MA: Yes. There’s been a sea change of empathetic reportage, but there’s still this urge to prepare the reader; to set up parameters for the presumable mainstream to understand what they’re about to experience.

TB: Yeah, I mean, I have no objections to people calling it “weird”. I just think that weird shouldn’t be taken as a negative. That is coming from someone who has spent four years in a private art school being taught that “you are unique and valid and people want to hear what you think!” though. It’s hard to see the water when I’m in it.

MA: I’m wondering if your goal has changed since you began, or if your focus has shifted as you explore more and more niches within furry. I imagine it’s become difficult to broadly summarize.

TB: Hmm. When I began the project, first semester of my freshman year in college, it was definitely not such a grand ordeal! It was just supposed to be a three-week assignment for a class. I went to a few furry meet-ups and took a couple REALLY BAD pictures. I then nervously talked to my classmates about them and tried my best to steer the conversation away from sex and how these people were all nerds, I’m sure I seemed SUPER defensive and secretive and in denial. Of course I’m not saying that it’s all about that now, but when you act defensive it draws a lot of attention. For a while I thought “Oh maybe I’ll do documentary work on all sorts of different fandom cultures”, but I’ve let that go. I know a lot more about Furries than I do Bronies or Trekkies or Anime kids.

MA: The ways furry is distinct from fan culture are more proliferate than the similarities I think.

TB: I agree. There is a much larger focus on social interaction than media consumption, especially with actual “fandom” behavior. Artists and creators of furry media are much more integrated into the social community than any other fandom. There isn’t one source point or gold standard for aesthetic or content or anything other than the rough guide of “animal people,” which is SO broad. I feel like furry is distinct in the sense that it’s a perfect storm of attributes that no other culture currently holds. Furry is a community that lives on the internet, but isn’t necessarily ABOUT the internet. In the same way, its a community full of transgressive sexualities and gender queering and such, but it isn’t about that either. It’s also a community that is by-and-large, self sustaining. Furries create their own messageboards, set up their own conventions, build their own costumes, etc. For the most part, furry is completely outside of capitalism; well, big capitalist culture, except for hotels and food. We pour a lot into that by way of conventions.

MA: Fursuits are of course the most publicly visible aspect of the fandom, and they’re a major focus of your documentary. Is it challenging directing subjects with masks with a static expression for photo shoots?

TB: (Laughter) I go back and forth on how I feel about the dominance that fursuits hold in my photographs of the community. On the one hand, I know that furry culture isn’t all about fursuits. On the other, I know that fursuits are probably the most visually unique and perplexing element of the community, as compared to what the rest of the world may offer. The fact that fursuits are (by and large) static in their expression, is very important, I think. It ties directly into their appeal. Imagine if your hair looked exactly how you wanted it to all the time, multiply that feeling towards your entire outward appearance. Fursuits are made to look exactly how you want, and they stay that way. They don’t age. The nature of the costumes is also to simplify expressions, and those simplified features are more powerful in their ability to please. They just look nicer. Because they’re in costume, and because their costumes don’t have as good of vision as a normal person, it’s actually a lot easier to photograph fursuiters, I think. They are less self conscious of the camera, because they are confident in their appearance, and simply put, it’s easier to sneak up on them. Also no one ever blinks.

Tommy Bruce / Fraulein in her home with partially constructed fursuit head, Baltimore, MD, 2012

MA: People have no small amount of difficulty beholding fursuits as sexual expressions, but I think you communicate that quite well. I’ve just been present for one of your more intimate shoots, but it was fascinating. Do you think that it’s something that you have to intrinsically “get” or can it touch on some more universal aspect.

TB: As in, the attractiveness of fursuits?

MA: Yeah! I can certainly remember my epiphany moment when I finally saw a suiter as really hot.

AboveTommy Bruce / Ari, Midwest Furfest, Chicago, IL 2013

Below: Tommy Bruce / Shea, Anthrocon, Pittsburgh, PA 2013

TB: Me, too. I think if people could just get over the idea of sexual transgressive acts as bad, there would be a LOT of people more interested in fursuits. I’ve had so many friends tell me about wearing their fursuits to non-furry social events and being secretly propositioned.

MA: WOW.

TB: I know, right! Some people are just turned off by the idea of a person in a costume; the idea of a stranger. I can understand that, and I recognize that it is not everyone’s cup of tea. But sort of like I mentioned in photographing them, fursuits are like cartoons in that they are simplified representations. More simplified means clear, more relatable, easier to understand, and sometimes out of that more pleasing. I remember having a conversation with a furry friend about where the attraction to furry characters came from. Being young and gay, he told me he felt intimidated and uncomfortable with most gay porn.

MA: Me, too.

TB: It was all mechanical pumping and gruff dudes and so on. Furry characters permeate our world, on cereal boxes, on TV and in books from childhood. So they were more familiar, and seemed less shameful. I know that isn’t everyone’s experience, but it’s one that makes sense I think.

MA: What has been your experience with resistance? Furries who didn’t want to be completely open at the time.

TB: Hmm, I’d have to say that at almost 4 years in, I don’t experience much outright anymore. I have found select members over the years who have grown used to me having a camera around all the time. I try to be conscious of when are good times and bad times to be photographing. I generally don’t use my camera very much when I’m entering into a room party of a person I don’t know well. I try to be as covert as possible in my setup, small lens, no flash and so on. I have a feeling that problems will creep up more as I come closer to publishing work. People fear that, somewhat falsely I think, but the resistance has certainly lessened over the years. At this point, a lot of people seem to know of my blog, and those that don’t don’t pay me much mind. Where there are fursuits, there are cameras. I’m trying to get closer to photographing individuals in their lives away from conventions, and that does bring some hesitation, but I have not received much outright denial so far (knock on wood).

Tommy Bruce / Shiacoft (head off), New Years Furry Ball, Wilmington, DE 2012

MA: Do you think furry can survive in a fractured state, considering recent events? Because I’ve discovered many furries are proving resistant to the idea of furaffinity’s centrality being challenged.

((AUTHOR’S NOTE: I am referring to a controversy involving Furaffinity, the largest online Furry social network. FA admins recently placed in a position of authority on the site a popular furry artist who has been accused of multiple instances of sexual harassment, coercion and assault. Many furrs have left the site as a result, citing among many grievances a lack of a culture of accountability among furry “leadership.”))

TB: In terms of what I’ve felt, we’re already somewhere in the transition to a different era of interaction in the furry community. Most of what I see, and a few friends have expressed similar feelings, comes from places like tumblr and twitter now. FurAffinity kind of feels like bad Facebook to me at this point. I go on to see if anyone said anything to me, I absent-mindedly add people when I meet them. I occasionally browse artworks. I think it’s possible that a new site will come to take it’s place, but I also think that it might be a while before that transition fully happens. There is definitely something to lament about, in the scattering of the community away from a single hub, but that is kind of the way things go.

Tommy Bruce / Mouse, Midwest Furfest, Chicago, IL 2013

AUTHOR’S NOTE: This is a picture of me that I commissioned from Tommy.

MA: I know plenty of furrs who are eager for a clean break, with the desire to coalesce the community around an explicitly progressive ideology.

TB: I definitely think this won’t spell the end for the furry community. If anything, furry has been on a steady rise in the last few years. I suppose this is where my documentarian instincts come in. Personally, I would really rather only be around other progressive and open minded individuals, but the observer side of me is a little weary of trying to create some utopia kind of environment, for fear of exclusion and stagnation. I may be unsure of my feelings (!!!)

MA: it’s hard to parse, it’s that unlimited aspect that allows furry to thrive, but so many people see it as a safe place from the world, which allows itself unlimited access to oppress them.

TB: Yeah. To be clear, I think what is going on with the higher ups at the current site is awful. Everyone fleeing is only what they deserve, and I hope at the very least the conversations that come out of this uproar can lead the community to be more aware and averse to rape culture and rape apology.

Tommy Bruce / Frisky in his room, Brooklyn, NY, 2013

MA: What are you plans for the future?

TB: I’ve got to get started on my grant proposals. There are a lot of travel grants that go out around this time of year. I’m hoping I can land one to take the next few months to travel across the country and spend extended time living with and photographing a few furries. I know one plan is to make it out to see Brian and Alison of Wild–Life Fursuiting Company fame, and stay with them while they make fursuits, and wax philosophical on the community. That and a few other west-coasters and perhaps a few cons, are hopefully in the works for the rest of 2014. During that time, I’m also planning on putting together a draft for what would be the REAL Furry Doc book. Collected writings, interviews and photographs from all of my travels, to go out as the first real extensive art documentary book on the fandom. That’s all pretty optimistic, but I think doable, if the stars align. I’ll continue photographing after/if the book comes out, but I’ll probably be trying harder at getting work in galleries, both from my documentary and with my other photo work I’m making.

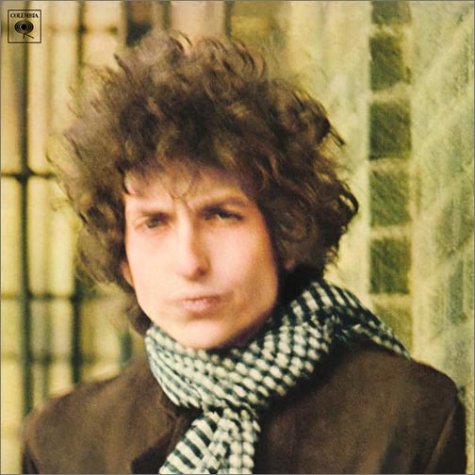

Tommy Bruce / Self Portrait in hotel mirror with Hyena Sharpie tattoo, FurTheMore, Baltimore,MD 2013