1960, and I am 6 years old; I leave the New York Public School system for my first day at the Lycée Français de New York, the city’s French school. (I’m half Yank, half Frog.)

At the end of the day, my mother rewards me with a comics album; it features a hero I’ve never heard of, in his first adventure — Astérix le Gaulois. It was the start of a love affair that lasted until the death of the comic’s writer, the brilliantly funny René Goscinny (1926-1977).

René Goscinny

The team of Goscinny (script) and Albert Uderzo (art) produced 24 albums of adventures for Astérix and his hulking sidekick Obélix. The series sold fairly well at first, but by 1965 it had become a hit phenomenon, one that grew and grew from year to year.

Goscinny and Uderzo at work; art by Uderzo

Alas, Goscinny died too soon, age 51. His partner then made a fateful decision that would prove financially successful but artistically disastrous: he would continue the series alone.

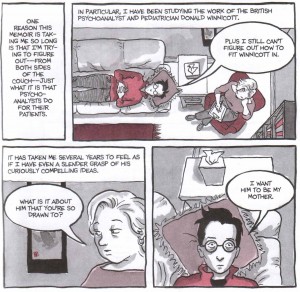

It’s part of received wisdom that the best comics are the product of a single writer/artist, and indeed there are many examples to support this view: Schulz (Peanuts), Herriman (Krazy Kat), Crumb. It can also be persuasively argued that even cartoonists who did good work in collaboration with others, for instance as scripters (Harvey Kurtzman) or artists (Jean Giraud, Barry Windsor-Smith) did their best work solo.

The Goscinny-Uderzo team tests this tenet. Goscinny was a mediocre cartoonist who wrote excellently. Uderzo is an excellent artist…who writes very badly.

The classic team at work…

Where Goscinny had impeccable comic timing, Uderzo’s lame gags seem to plop onto the page. Where Goscinny’s stories were intricately plotted, Uderzo’s are simplistic good guy/bad guy fables with sentimental love tales woven in. Goscinny wisely limited the fantastic element mainly to the famous Magic Potion that gave Astérix super-strength; Uderzo crammed his albums with flying carpets, unicorns, Atlantis, giant babies, flying saucers and all the fantasy paraphernalia you could wish for — or not. (Actually, I have a sneaking sympathy for the artist on this last point: he had probably felt frustrated by decades of not being able to draw all this cool stuff…)

I could go on in depressing detail, but suffice it to say that over the course of eight albums what was once widely hailed as the world’s best comic, beloved of kids and adults alike, had descended into a silly, wholly childish mediocrity.

But in business terms, Astérix had become a colossus.

To give some perspective, consider that the first edition of the first album, back in 1959, was of 6000 copies. In 2005, Uderzo’s last album had a first edition of three million two hundred thousand copies — and that’s just the French language version.

Published in 110 languages, Astérix has had to date total worldwide sales of 350 000 000 copies. It has spawned 8 feature cartoons, 4 live action feature films, and an amusement park. It currently has over 100 product licenses. This is a billion-dollar property.

And one which has turned Uderzo, especially since he took over the publishing himself, into one of the richest men in France.

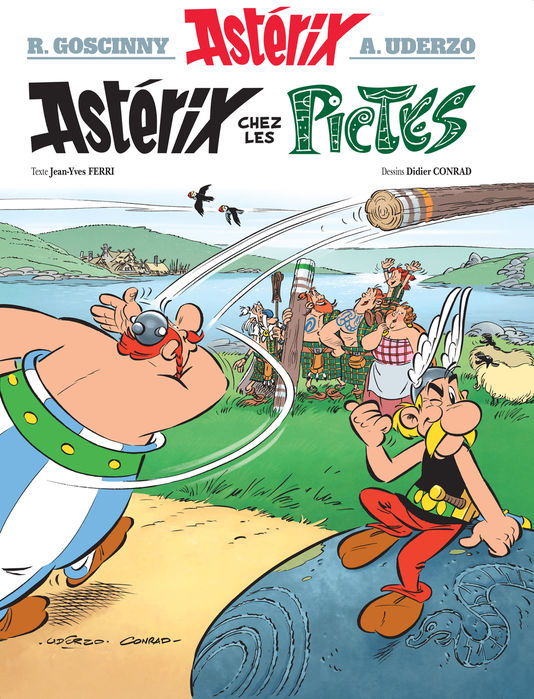

But the artist is now 86 years old, and determined to retire. At first he thought of discontinuing the strip as well…then decided to turn it over to a new team: scripter Jean-Yves Ferri and artist Didier Conrad.

Left to right: Jean-Yves Ferri, Albert Uderzo, and Didier Conrad

It’s not a choice a purist would wish, perhaps, but one can understand the impulse behind it. Uderzo is probably hoping to pass on a living, profitable legacy to his descendants (though as of this writing he’s embroiled in a nasty lawsuit against his daughter.) He might also feel a duty towards the employees of his company. Who knows? He might simply have thought it fun to oversee the work of new blood.

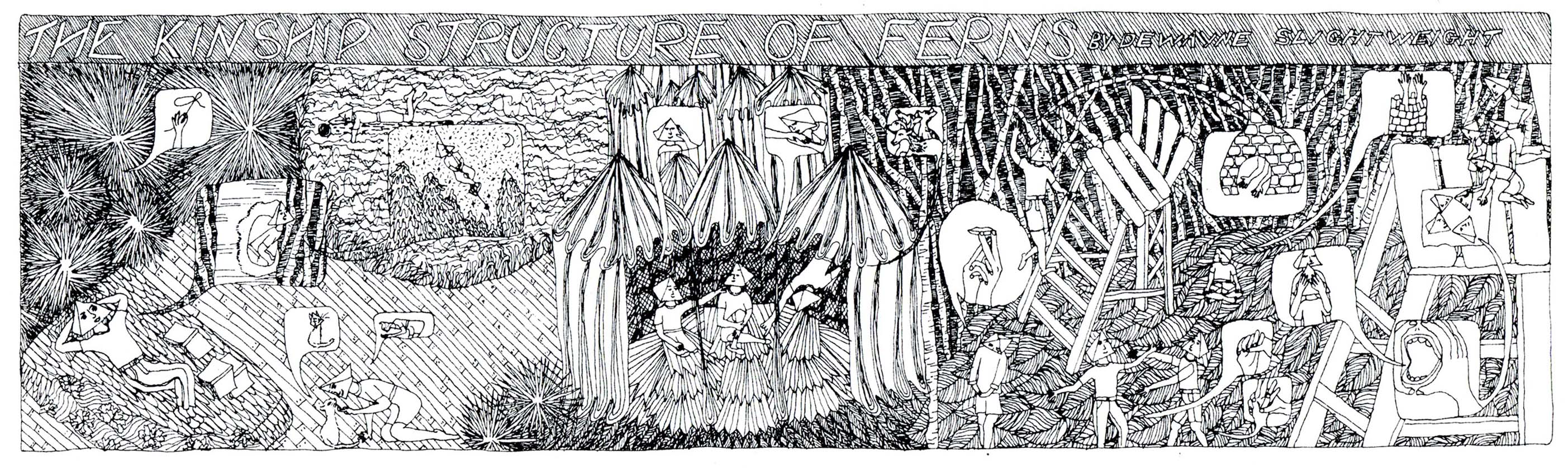

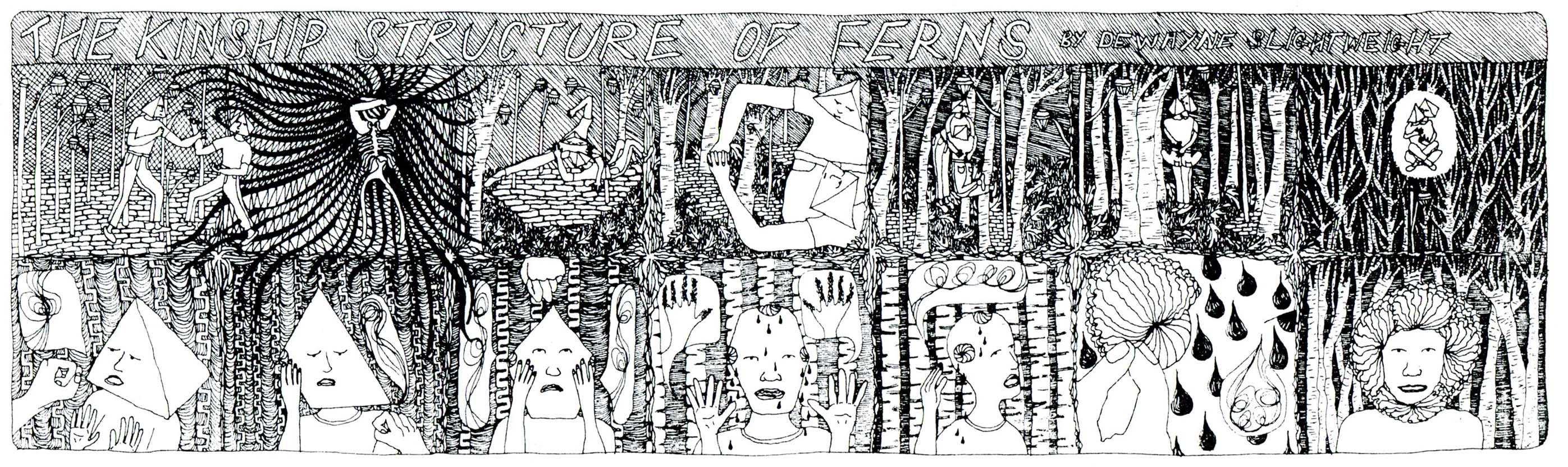

Ferri (1959– ) was best known for an album of mildly whimsical gags, De Gaulle à la Plage. Conrad (1959– ) was once considered a satiric and scatological enfant terrible of Franco-Belgian comics — little trace of that here — renowned for his skill at imitating classic cartoonists such as Franquin or Morris; this latter talent is, no doubt, the reason Uderzo chose him.

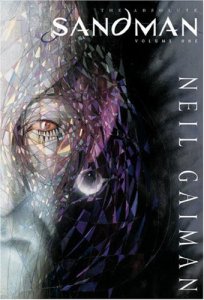

October 2013 saw the release of the new team’s first effort, Astérix chez les Pictes.

My verdict, and that of most reviewers: FAIL.

Some background: Astérix, in album after album, would visit a foreign land, and the people dwelling there would be satirised: Belgians, Swiss, Spanish, Germans (the only ones treated really viciously: understandable, perhaps — the Jewish Goscinny lost part of his family to the Nazi extermination camps.) By common consensus, the best of these particular albums is Asterix in Britain, a hilarious send-up of the English, who themselves loved it.

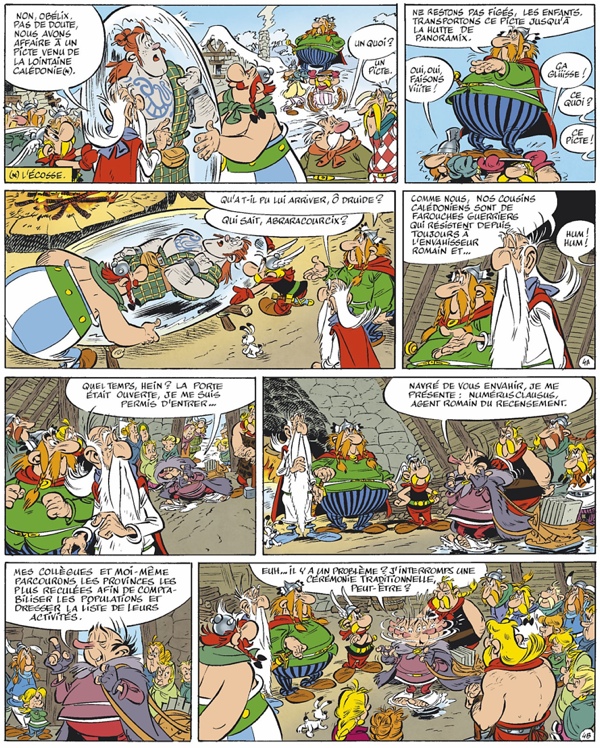

The target country this time around is Scotland. (The Picts were the Celtic tribes who pre-dated the Scots in what the Romans called Caledonia.)

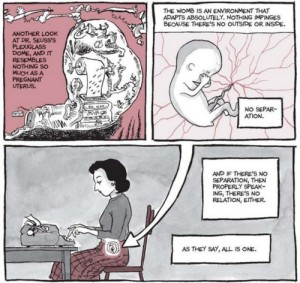

Now, not everybody likes these national parodies, and indeed one may argue that they reinforce stereotypes and xenophobia. (One comics scholar of this opinion I found rather persuasive is Domingos Isabelinho.) However, if you’re going to satirise, then do it: don’t turn out soft-pedal mush!

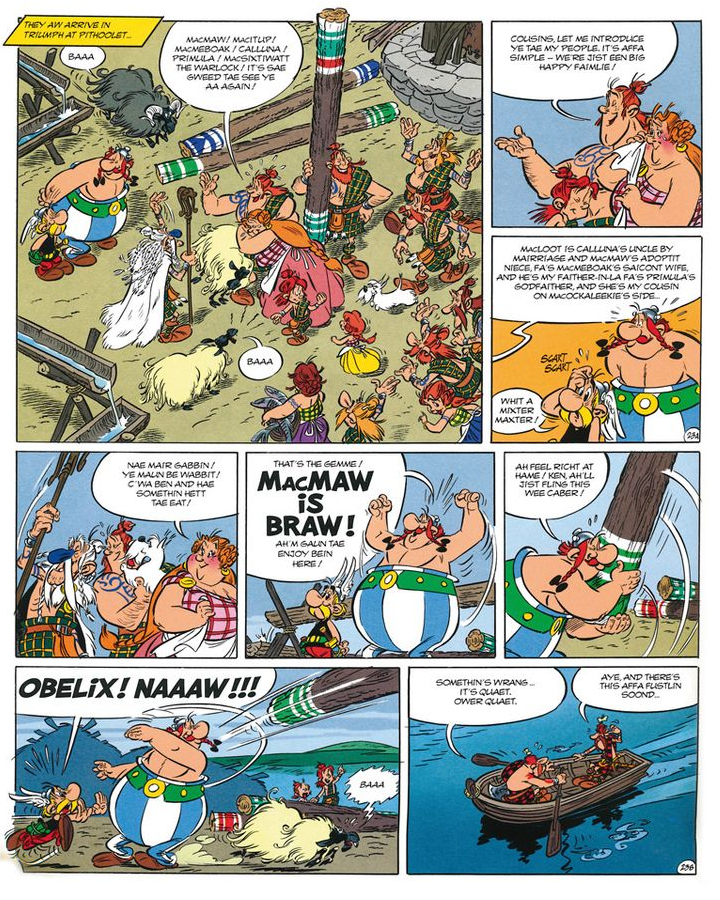

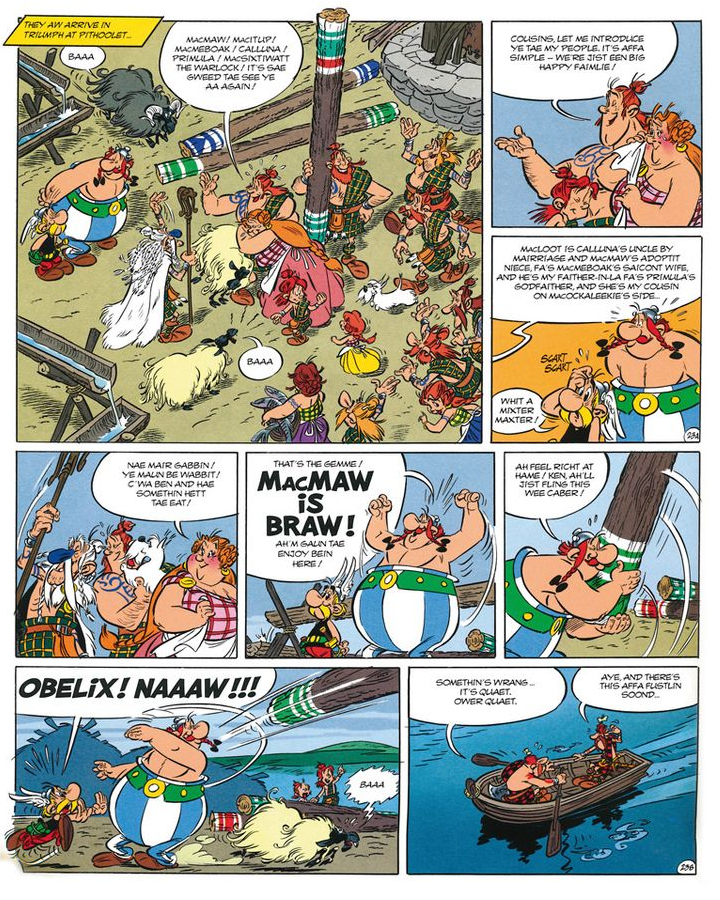

Alas, that’s exactly what Pictes does. There’s some wordplay on Mac-prefixed names, fun at the expense of clan tartans or of the Scottish sport of caber-tossing, teasing about the potency of proto-scotch whisky…and that’s about it. I’m not asking that Ferri dig up the more nasty clichés about the Scots, especially the libelous legend of their niggardliness. (I’ve travelled in Scotland, and have found the Scottish people to be of extraordinary generosity and kindness.)

But why such blandness? It’s telling that throughout, the Gauls and the Picts call each other “cousin”. That’s what we get here: the Picts/Scots are just Gauls/French in kilts.

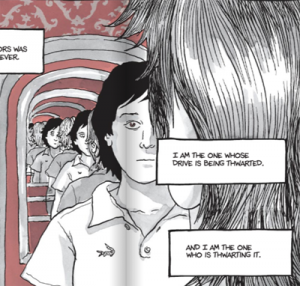

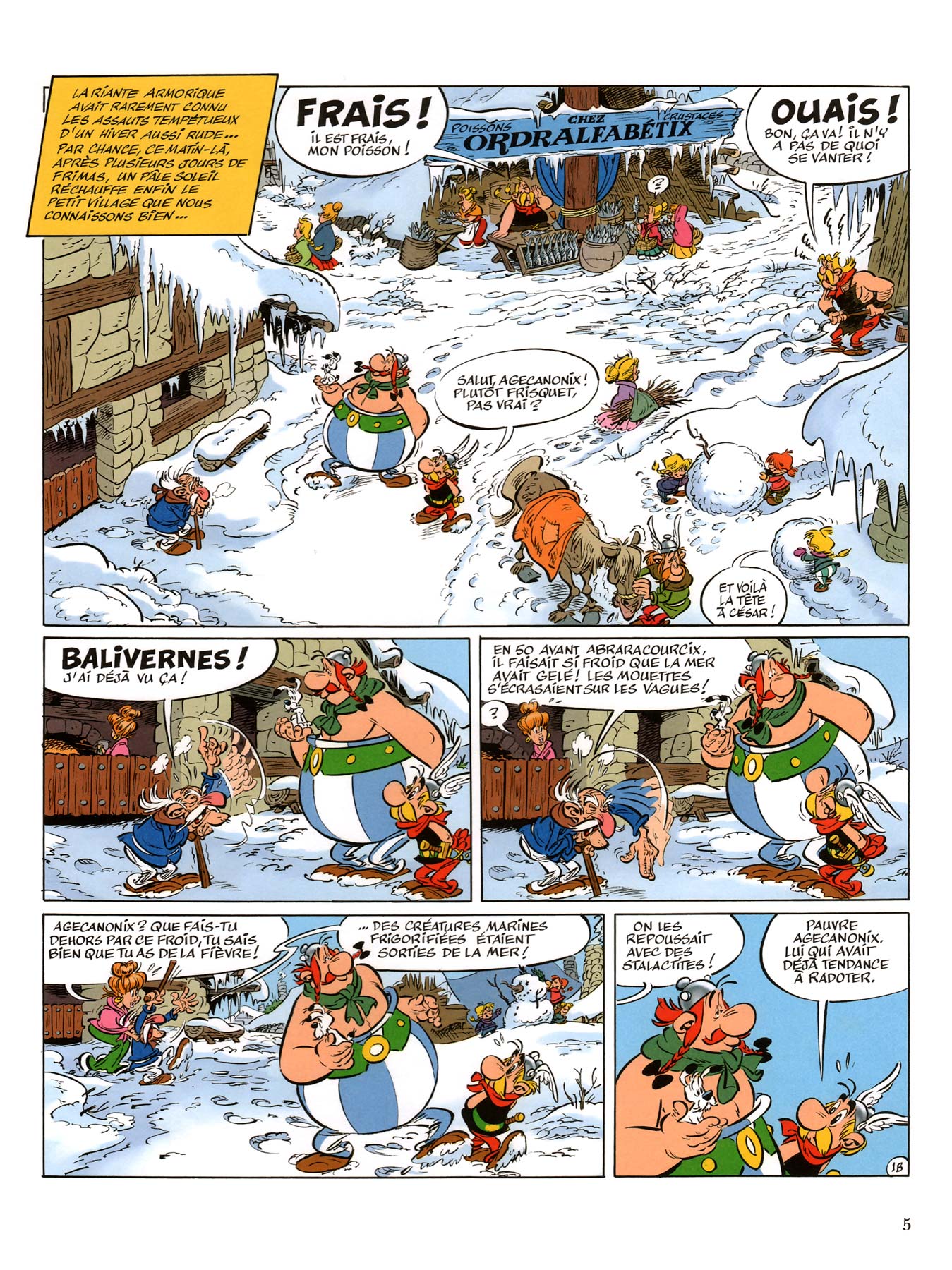

Well, on to the story, such as it is. It’s winter in Gaul, and Asterix and Obélix find a young Pictish man frozen in ice:

Once the Druid thaws him out, the Pict is unable to speak at first, but manages to carve a map to his home village.With Asterix and Obélix they set sail — which naturally means the traditional running gag of trashing the pirates. (The Pict, Mac Oloch, recovers his power of speech.)

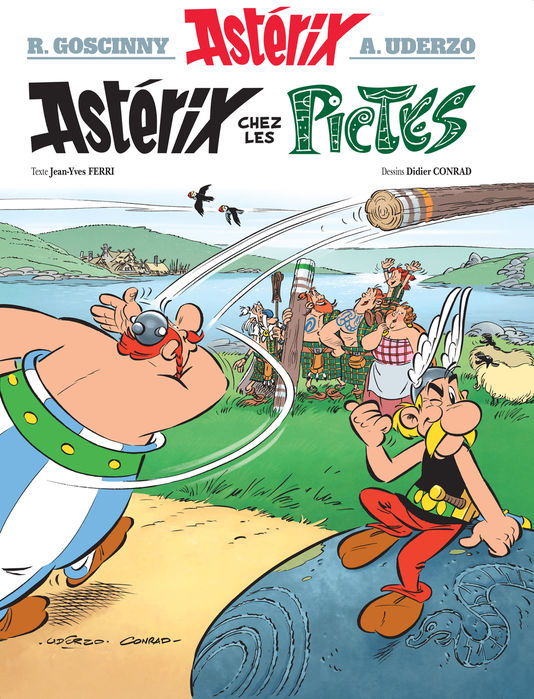

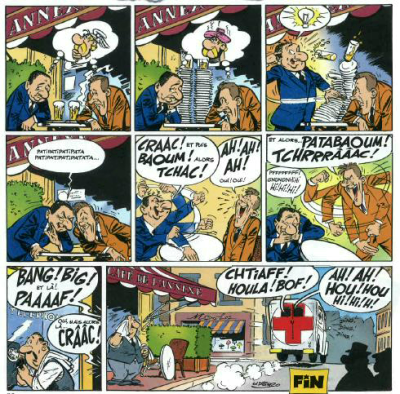

The pirate fight seems unusually bullying this time around — as a rule they do something to bring down Gaulish wrath on their heads. This time it’s see-pirate, bash-pirate: gratuitous violence:

(The above image shows a recurring flaw in Conrad’s impersonation of Uderzo: the latter was very good at clarity in complex set-ups — his successor, not so much.)

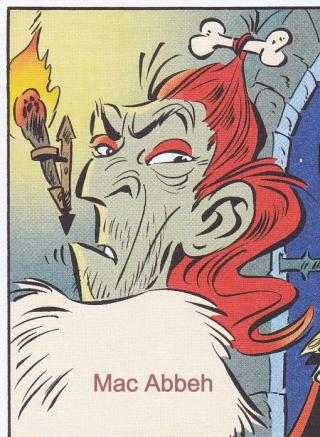

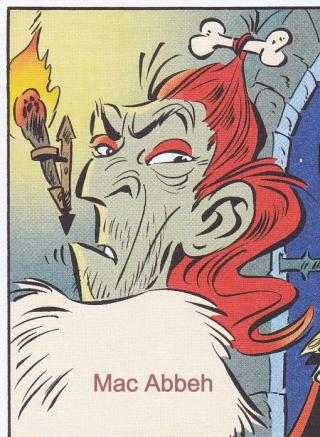

They get to Caledonia, there’s a big welcome back, and the goodies vs baddies scenario is laid out. The villainous Mac Abbeh is scheming to take over as Great King of the Pictish Clans, and he’d caused Mac Oloch’s supposed frozen doom to set aside this rightful pretender, as well as to steal his fiancée Camomilla. He’s also plotting with the Romans to have them invade Caledonia (which they never managed in real life).

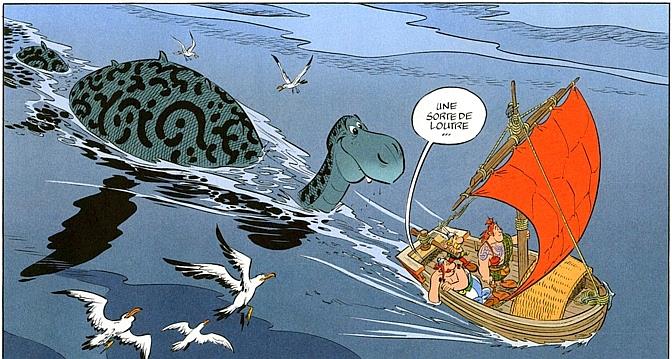

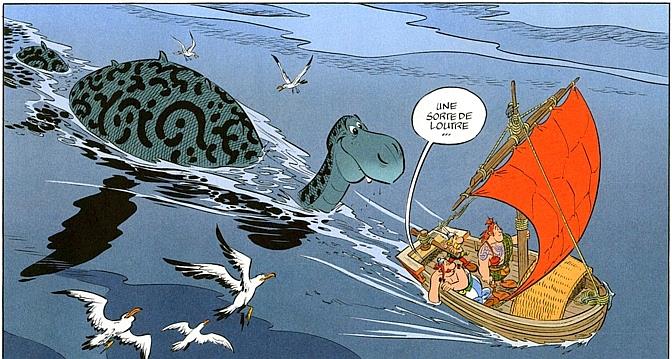

Our heroes set to work undoing this villainy, as usual with plenty of smashing the enemy, interspersed with salmon feasts, joking assimilation of Pictish bards with rock groups, whisky-sodden druids and Romans, and an excessively goofy-looking (and overexposed — see my complaints about too many fantasy elements) Loch Ness monster:

Goscinny would often slip in political or sociological commentary into his scripts. The closest Ferri comes to this is rather mean-spirited: during the final battle, in a free-for-all between warring clans, we note that each clan is distinguished by a tartan or other pattern, often ridiculous — polka dots and so on. The representative of the White Pict Clan bears the insignia of the Red Cross, and he proudly proclaims his neutrality — which leads to his being beaten up by both sides, to the evident approval of the authors.

The Red Cross (as well as its Islamic sister organisation, the Red Crescent) has always proclaimed and studiously observed its neutrality during war and conflicts. It has to. It otherwise couldn’t fulfill its mission of tending to the wounded and prisoners held by each enemy combatant. To sneer at the Red Cross for its neutrality is as distasteful an attitude as I can imagine.

Another annoyance for this olde farte of a reader: the series used to be stuffed to the gills with classical allusions, often of a very high degree of wit. None of that here. But I suppose I can’t really blame the authors. France in 2014 is not the France of 1959, when Latin was a compulsory subject in middle and high school, when most of the country went to the Latin-language Roman Catholic mass every Sunday (Asterix debuted before the Vatican II Council imposed the mass in the vernacular.) The country, and most of Europe, was steeped in classical culture. An age lost and by the wind grieved…

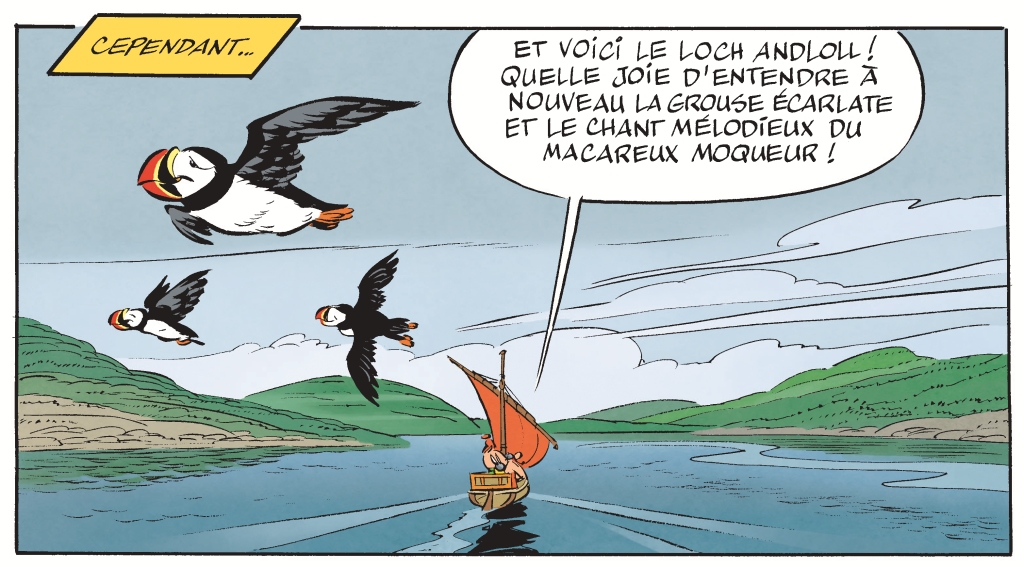

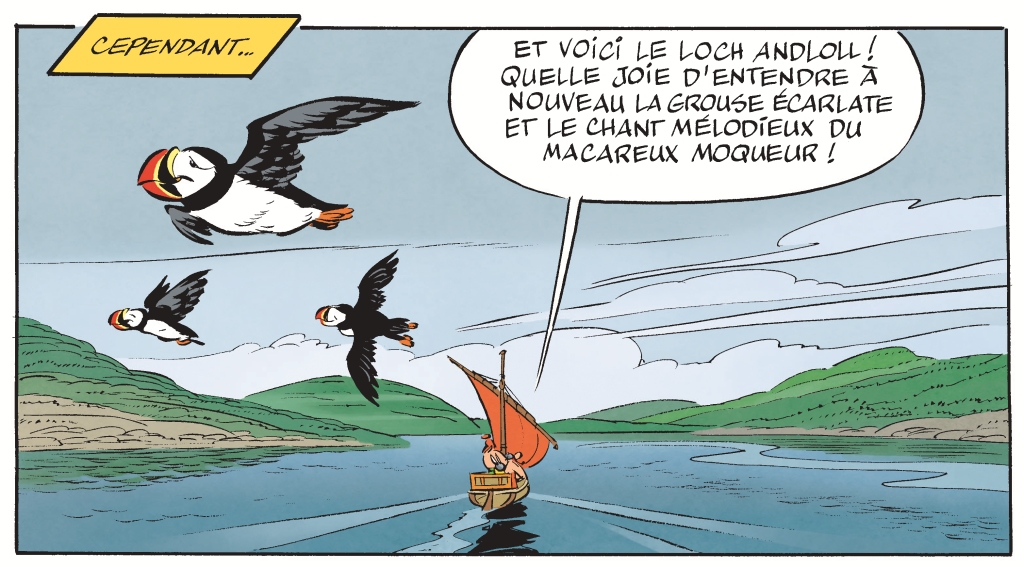

Are there any positive sides to the album? As I said, Didier Conrad is a pale echo of Uderzo, but sometimes his art can depict images of simple charm, such as this view of low-flying puffins:

MacOloch’s brain-damaged state is treated with genuine tact and sympathy, showing his sadness and frustration at being unable to control his speech:

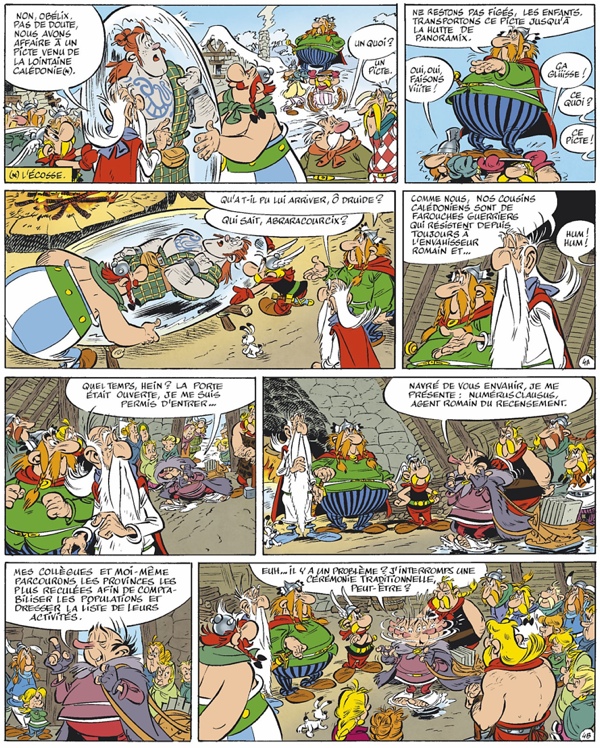

I liked how the entire Gaul village rallied around this stricken castaway with kindness and tact. There is a minor sub-plot concerning a modest but zealous Roman census-taker that I also enjoyed.

There is also the refreshingly feisty figure of Camomilla, MacOloch’s lady love. He’d described her in the most cloying, sylph-like romantic flummery — but when we get to meet her she’s a short, plumpish firecracker of a lassie with a temper and a quick-lashing fist. Even MacOloch is a bit afraid of her and of her heretical feminist notions about royal succession.

To sum up, the book isn’t bad as such. It’s mediocre, and mediocrity doesn’t cut it when it comes to a once-extraordinary strip like Asterix.

The English-language version is also out, as usual translated by Anthea Bell (1936– )

Anthea Bell

Bell is one of Britain’s most esteemed and honored translators from the French, German and Danish. Although she is noted for her work with adult literature (Stefan Zweig, W.G.Sebald, Sigmund Freud) she also has a considerable body of work in children’s literature (new translations of Hans Christian Anderson’s fairy tales) and comics. Her renderings of the Asterix books are remarkable, especially in her skillful versions of puns — the translator’s nightmare — and of cultural allusions.

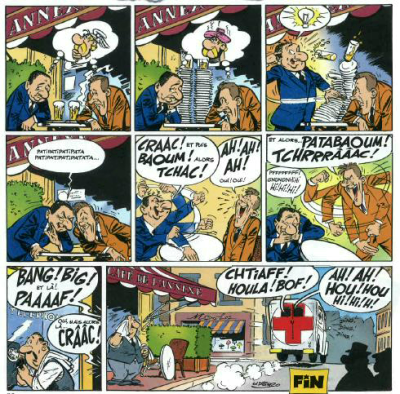

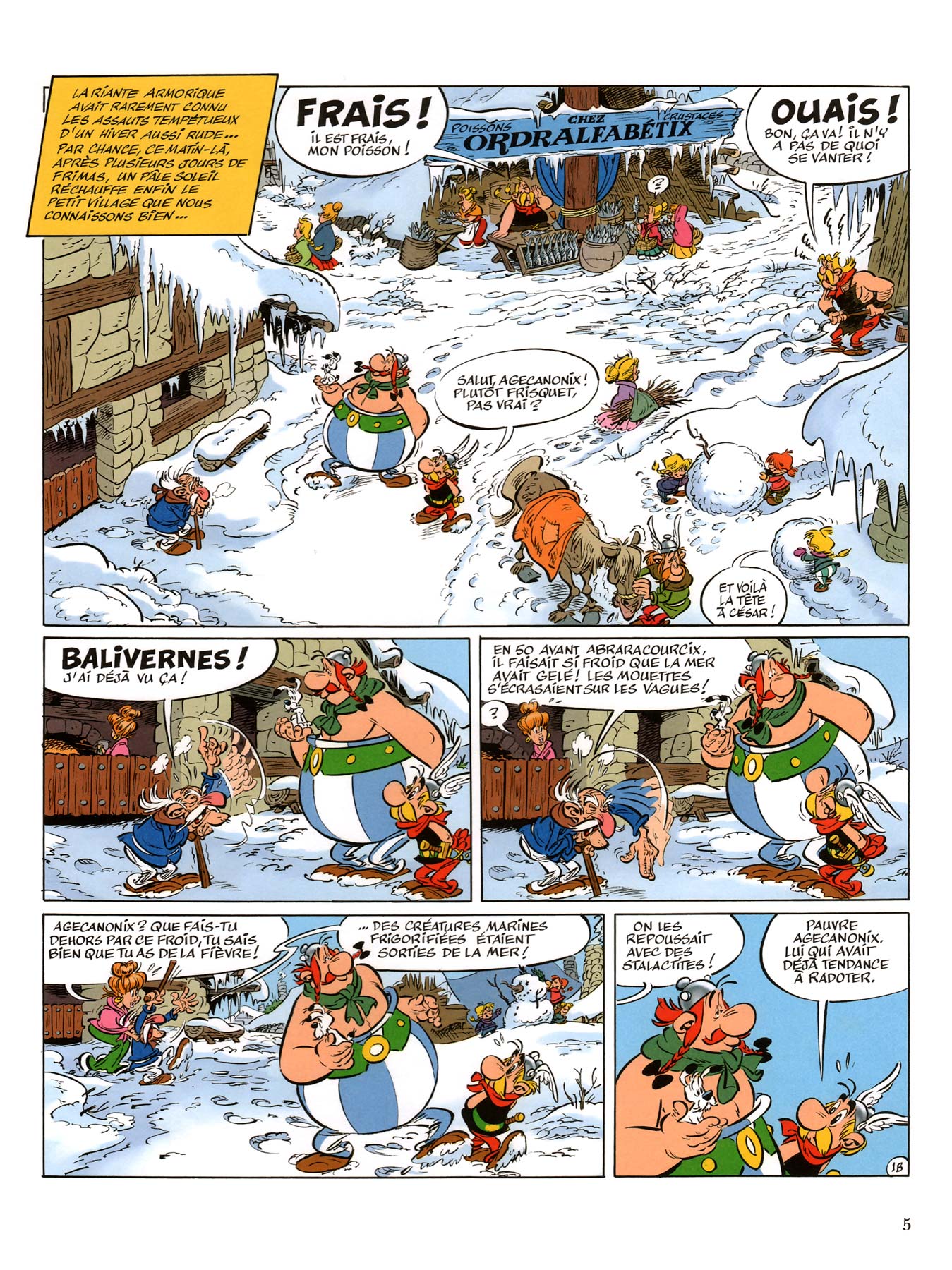

Alas, her work here really can’t be commended. Uninspired is the best I can say. Look at the first panel in the page below, which carries on one of the series’ running gags, the enmity between the fishmonger and the blacksmith in the village:

Fishmonger: Frais! Il est frais mon poisson!

Blacksmith: Ouais! Bon, ca va! Il n’y a pas de quoi se vanter!

There’s a pun at work here. My literal translation:

Fishmonger: Fresh! My fish is fresh!

Blacksmith: Yeah, yeah! That’ll do! That’s nothing to brag about!

Now, the caption and the graphics tell us that this is an exceptionally cold winter. In French, “frais” can mean either fresh — as in ‘fresh fruit’ — or cold. So the punning meaning implied by the blacksmith is that his old foe is bragging about his cold fish, and so what in weather like this?

Whew. How do you translate a pun like that? Don’t ask me, but in the past Bell has pulled off miracles in this linguistic minefield. Not here, though: her translation runs:

Fishmonger: Fresh fish! Buy my nice fresh fish!

Blacksmith: Huh! Fresh, is it? Tell us another!

In other words, Bell doesn’t even try.

Mind you, she can’t be blamed for making bricks without straw. At one point the Picts welcome Asterix and Obelix with a feast of “paupiettes de saumon”, salmon paupiettes. Now, paupiettes are thinly sliced pieces of meat wrapped around a filler of vegetables and stuffing. But Conrad just draws whole salmons in the dishes. Poor Bell can’t remedy this laziness by just calling them ‘salmons’, as there’s a whole little shtick about Obelix loving the dish and asking for the special recipe. So Bell calls them “salmon portions”.

(Foreign dishes are a recurring source of humor in the series. So why didn’t the authors mention the most famous dish in Scotland, the haggis, a meat pudding wrapped in a sheep’s stomach? Even the Scots make fun of it, vide Robert Browning’s ode to haggis (“Fair fa’ your honest, sonsie face, Great chieftain o’ the puddin’-race! Aboon them a’ ye tak yer place, Painch, tripe, or thairm: Weel are ye wordy o’ a grace As lang’s my airm.”). My guess is that Ferri and Conrad didn’t want to invite comparison with one of the most famous skits in French radio: La Panse de Brebis Farcie, by Fernand Raynaud, about a Frenchman’s desperate attempt to avoid eating haggis.)

My main beef is that Bell made no attempt at reproducing Scottish dialect. All her Picts speak like London schoolmistresses. This is all the more bizarre as there’s also being published the entire album in Lallans, or Lowland Scottish English, as shown below:

(It’s also being published in Gaelic).

Finally, a last reason for my disenchantment. Comics are big business in France. The combined first printing of Picts comes to 4 million four hundred thousand copies, with 2 million two hundred thousand for France alone (at nine euros a pop- about $13…you do the math.) An Asterix album is given the media and advertising saturation launch of a Hollywood movie. For weeks, you couldn’t avoid the damn thing. Enough already.

Poster in the Paris metro

The problem of the legacy strip is common to France and the USA. In France, sequels to many popular series like Blake et Mortimer come out after the creator’s death, as do strips like Flash Gordon or Annie in the states. Other strips are permanently retired: Tintin, Peanuts. Which is best?