Trying to figure out the exact point of Zen Pencils has not been easy. Created and written by Australia-based cartoonist Gavin Aung Than since 2012, it is at least usually a series of comics about inspirational quotes made by famous people, a sort of Chicken Soup for the Cartoonist’s Soul. With its feel good premise and emphasis on inner creativity, self-realization and the transformative power of a single out-of-context quote, it isn’t surprising that the comic series has been since its inception a hit on Facebook walls and Pinterest boards alike. Whether or not you recognize the author, if you’ve seen a comic floating around about a quote by Carl Sagan, Helen Keller, or Theodore Roosevelt, chances are you’ve seen some of Aung Than’s work. Though not all focused on unrelenting positivity, the vast majority of Zen Pencils comics are small and quickly gratifying fell-goodisms, nuggets of good vibes that find their ideal germinating ground in the digital networks of chain emails your uncle likes to send out. Yet at the same time, Zen Pencils has long had an underlying current of negative, vitriolic vein of thought running through it, expressed in angry comics on teaching, the terrors of post-graduation life, and the impact of technology on society, among others. These comics received a certain degree of notoriety for this, and, as this is the internet, a certain degree of trolling directed at Zen Pencils in general and Aung Than in particular. But it is not these initial comics that the crux of Zen Pencils’ notoriety rests on, but rather the way Aung Than responded to his critics; by creating a massive, four part comic about the evils of his interlocutors. It’s an ignominious, textbook example of how one should not respond to criticism.

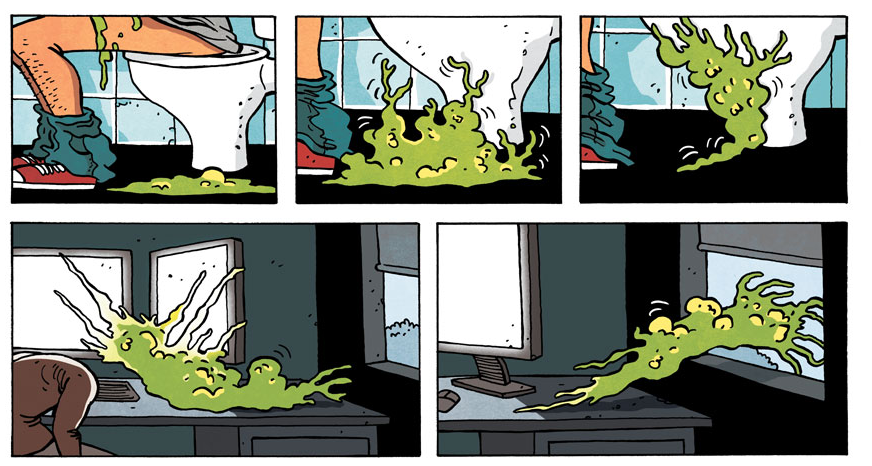

The comics begin with a group of internet critics and naysayers, apparently quite literally full of shit, bursting into piles of green sludge randomly and violently. As more and more cardboard cutout cynics meet their fate this way, the green sludge begins to take form, transforming into a massive slime monster aptly titled (and with a hashtag) #hate. To counter the threat of #hate, which threatens to engulf all creativity and art in the world, an anachronistic group of artists led by one “H. Miyazaki” (copyright issues and all) gather together and, with veritably Captain Planet like gumption, form a giant mecha robot called A.R.T., emblazoned with an inspirational quote by Theodore Roosevelt, and blast off to fight the evil #hate in a climactic showdown. When they finally succeed in the comics’ thrilling conclusion, they take the entrails of their slain adversary, fly to the moon, and write the word ART on its surface as a message (and perhaps a warning) to all those who may question and criticize art.

Be afraid, my fellow HU critics.

There is so much going in this bizarre four part comic, written by a man best known for writing feel-goodisms about Albert Einstein and Helen Keller, it’s difficult to know where to begin. For long-time naysayers and critics of Zen Pencils, this vociferously anti-criticism criticism is going to do little but validate their objections, that Aung Than’s work is little more than moralizing, didactic tripe that doesn’t see the world with nuance. And in doing so, of course, they will only reinforce Aung Than’s position that critics are hacks at best and slime beings at worst. So where is there to go from here? It seems all too easy to dismiss the Art vs. Hate comics as angry, senseless diatribes, long winded rants in the vein of a public meltdown, but there’s a clear form and directionality to these comics that your average twitter breakdown lacks. Aung Than has planned out these comics thoroughly, and released them successively, each within a few weeks of each other. Several weeks to a month seems a long time to hold onto the white hot rage the comics seem to project, so what is their purpose? Aung Than is clearly making a statement, however confused and angry, and this in itself seems worth at least trying to unpack. What he ends up expressing is not a rant so much as a Manichean prophecy, a declaration that we live in a world of light and dark, art and criticism, #hate and #create. And we – all of us, from immediate readers to anyone with a stake in the exploration of art itself – must take a side. Will we stand with the artists, and try to create? Or will we be swept away as critics, like so many little slime monsters?

The glaring weakness in Aung Than’s dichotomy is the weakness of most dichotomies – that the binary they are predicated upon does not really exist. In writing this article, I am at least ostensibly in the position of critic, but I do not think of myself solely as such, and dedicate much of my time to my own creative endeavors. Does this make me a critic, or an artist? Am I made of slime and hate, or goodness and creativity? In truth, I and most people are a holistic mix of both. Criticism is not inimical to art; it is the molecular reaction, the most basic process, through which art of any sort is created. Art doesn’t emerge from a vacuum; it is created in response to the world, indeed as criticism towards it, and art evolves as an active process of criticisms and reassessment across decades and centuries. The Realists would not have emerged were they not critics of the Romantics; Postmodernism would never have occurred were it not for the faults present in Modernism. The moment we strip art of its critical dimension, we strip it of its ability to grow, to change, and to affect us. Art, if it is to serve a purpose, cannot simply stop being critical or subversive when we deem it so; it cannot be made for its own sake. And if you will forgive me for trying to answer the forbidden ‘what is art’ question, I would say that art exists to inform, to reflect, and to critique, and the moment it ceases in this function it is no longer art. It is something else entirely.

I hope #Hate isn’t #trending.

Is this what Aung Than wants? To strip art of its critical component and make it a dead and static thing to be hung up on a wall and endlessly gestured to? I do not think so. Zen Pencils is based on the words of wisdom spoken by some of the most notable figures in our world, and many of those figures quoted are indeed artists. Imagine a world where artists did not exist to say inspirational things! What would Zen Pencils, Hallmark, and the chain email enthusiasts of the world do?! The horror! But in all truth, in evaluating the Art vs. Hate comics, my suggestion would be for Aung Than to think back to one specific character; H(ayao) Miyazaki, his self-described biggest idol and influence. What is it about Miyazaki’s work that he appreciates the most? What does he try to emulate, and what makes it worthwhile to him? Criticism is not merely an act of negation; it is as much choosing what to keep in creative endeavors as it is figuring out what to leave behind, and what to oppose.

I do not say any of this to condescend to Aung Than or his work, for when it comes to mindlessly negative internet trolls and their detrimental impact on discourse and the creation of art, we are in total agreement. The nastiness directed towards Zen Pencils does not constitute good criticism, but the comics as a whole could stand to realize that there is more to the process of creating than empty eulogies. In raising art to a pedestal-beyond-pedestals, Zen Pencils does not enshrine art, but merely the idea of art, an empty rhetorical figure used metonymically to refer vaguely and uncritically to everything good and pure in the world. This emptying out of art, so to speak, is not a new phenomenon; defending art for art’s sake, as if art exists independent of the world from which it arises and must be bulwarked against that very world, is a common and noxious idea that gains ground whenever one speaks of art as a goal in and of itself. It is easy to appreciate art, to worship the very idea of it and identify it as the sentinel against which all the evils of the world are kept at bay, but this is tantamount to a betrayal of art itself. Art does not preserve the world, nor does it transcend it; art creates the world, and to criticize is to define and create art itself. We make art not to transcend the world, but to critique it, and make it a better place. And when we can fully recognize and appreciate this, then maybe Aung Than’s dream will be realized, and art will truly triumph over #hate it all its forms.

I’m not the first to point it out, but there’s something truly unfortunate about the idea that “H” Miyazaki would find much wisdom in the words of noted white supremacist and American imperialist cheerleader Theodore Roosevelt.

So, I agree with many of your points Patrick, but maybe disagree on the main thing, which is that you seem to think the #hate comic is bad, whereas I really like it. People exploding in eruptions of green slime; giant burping hashtag monster; Miyazaki giant robot emblazoned with Teddy Rooevelt slogan to the rescue — it’s really imaginative and weird and mean-spirited, and the cartooning is energetic and funny. It reminds me of Ax Cop to some degree, and of Johnny Ryan, two things I like a lot. It’s certainly infinitely better than his inspirational cartoons.

And the reason it’s better, I’d say, is the hate. You basically argue that art should have a critical function — and this cartoon does. He’s criticizing haters; that’s what gives the piece its charge. So I’d say that the #hate comic, while claiming to be a brief against hate, is actually a demonstration of why hate and criticism are so central to good art. Not least because it seems like this is a clear instance in which criticism of an artist’s work inspired the artist to create something better.

I have been following Zen Pencils off and on, and I always figured that Aung Than would be laughing at his critics all the way to the bank… I mean, surely it won’t be long before Hallmark or some kind of inspirational/self-help enterprise buys up the series, if they haven’t already?

But I think I can see what you’re saying… the comic does seem to equate any and all forms of criticism with trolling, and the line he selected from Roosevelt invites the same kind of generalization. That’s unfortunate, as is the juxtaposition of the actively engaged artists and the idle critics (love the guy on the toilet). But you could argue that Aung Than is putting his own quotable triumphalism into action here and, true to form, there isn’t all that much room for nuance.

The appalling thing about this kind of anti-critical diatribe — merely the latest in the long tradition of such tantrums from artists — is how profoundly elitist and anti-democratic it is. “How dare you respond to my art in a way I don’t approve of! I give you these gifts — the most precious things of all — and you give me scorn.” It divides the world into three — the artists, who are the ubermenschen to beat all ubermenschen; the grateful public, who know their place as merely happy recipients of the pearls of brilliance they’re thrown; and the haters, lowest of the low. Atlas fucking shrugged.

If it comes down to a choice between Than versus a sludge monster squished on the moon, then I’m with the sludge monster.

Ye gods. I thought this would be the most mortifying piece of art I saw today, but that comes close. Someday he’ll be embarrassed by that, I hope.

I looked at his archives, and he’s illustrated multiple quotes from George Carlin, Bill Hicks, Mark Twain, Kurt Vonnegut, and Hunter S. Thompson. Not people who shied away from harsh criticism! (What Twain did to Fenimore Cooper is a masterpiece of #hate.) How’d this guy wind up being such a sap?

(Also: the most recent quote he did is by Mother Jones. He also once did one by Ayn Rand. Only by emptying their quotes of all real content can you bracket those two together. And even though he acknowledges the irony, he should never have issued a call to adventure with a quote from Christopher McCandless.)

Two more thoughts —

First, what an impoverished conception of art this kind of tantrum shows. I’d go further than Patrick here; criticism doesn’t just lead to Art in the form of (e.g.) postmodernists writing novels, criticism — good criticism — is itself a form of Art. When Dorothy Parker quips of Hepburn that she ran the “the gamut of emotions from A to B”, that’s product of a playful wit. When Joe Queenan, incensed by the Joe Pesci/Danny Glover buddy comedy Gone Fishin’, becomes the Bad Movie Fairy, bailing up cinemagoing strangers as they leave bad movies and refunding them the cost of their tickets, doesn’t that show a rich creative imagination? When Nathan Rabin coins the term Manic Pixie Dream Girl, that illuminates something important about how cinema subordinates women to mere instruments of male self-actualisation. These count as Art just as much as anything Than has ever done.

Even the kind of crude snarky tweets that Than derides, they’re a form of folk art — an efflorescence of ultra-utilitarian creativity pour creativity. Than doesn’t like it, but he doesn’t get to be the Arbiter-in-Chief of Acceptable Art.

Second, further on the Rand parallel, does this strip make “Going Miyazaki” the new “Going Galt”? Of course, Galt just took his toys and went off to make his own society; whereas Miyazaki exterminates the untermenschen, so…progress, I guess?

In conclusion, fuck Zen Pencils.

So…am I the only one who likes that comic?

Why do you all gotta hate?

It’s relatively inoffensive in my book but the first part where the critics explode into green goo is probably the best part of the comic. It’s curious that you like it so much since it owes a lot to Calvin and Hobbes and Calvin’s monster fantasies. And I know you don’t like C&H that much.

I don’t remember C&H ever being that gory, or wandering off on such tangents exactly? Again it feels more like Ax Cop than Calvin and Hobbes.

I think gore (or sexual perversity) is antithetical to the Zen Pencils philosophy – it’s just a lot of gooey green bile like the slime kids used to play with. Completely PG 13 even with the fake exploding heads. The drawing style is just too cute to be compared to anything in Axe Cop or Prison Pit.

Aung Than may be angry but he’s as “nice” as the self-help quotes he illustrates on a daily basis.

This analysis seems flawed from the start. Than’s target isn’t criticism but trollism (fueled by hate/negativity), as made completely clear by its title, “The Artist-Troll War”, unmentioned here. Maybe because then it wouldn’t make sense to write most of the analysis?

Aung Than’s note, published along with the last chapter:

“The theme of internet trolls has been on my mind for awhile now. Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, comment boards … is it just me or is the internet being suffocated by negativity and hate? Not necessarily directed at my work but just in general. Maybe I’m visiting the wrong sites but everybody thinks they’re an expert and can’t wait to tell you you’re wrong, or something sucks and why the hell did that person even bother trying?

It’s time to choose a side. Are you on the side who takes the easy option? The troll. The armchair critic slinging snarky quips behind the safety of a keyboard. Firing sarcastic bullets at those in the trenches. Or are you a creator? Someone who makes something. Someone who lets themselves be vulnerable in front of an audience, who contributes something new and hopeful to an increasingly dark and depressing world. Choose. Which side are you on?”

I’d also go so far as to say that Than would place people doing serious criticism into the “Someone who lets themselves be vulnerable in front of an audience” group.

“It’s time to choose a side. Are you on the side who takes the easy option? The troll. The armchair critic slinging snarky quips behind the safety of a keyboard. Firing sarcastic bullets at those in the trenches. Or are you a creator? Someone who makes something. Someone who lets themselves be vulnerable in front of an audience, who contributes something new and hopeful to an increasingly dark and depressing world. Choose. Which side are you on?” — Aung Than, Zen Pencils

“Imagine the will it took to create a place like this. And what have you built? Nothing. You can only loot and break. You’re not a man, you’re just a termite at Versailles.” — Andrew Ryan, Bioshock

Ax Cop is cute!

I don’t think that really holds up, Pedro. It’s a no true Scotsman argument; if he happens to like you, you’re not a troll; if he doesn’t (because, for example, you’re criticizing him) then you’re a bad, bad person.

He’s being puerile and mean and stupid. Which, again, I kind of like about the comic. It’s better than vacuous high-mindedness, for sure.

I don’t see it as no true Scotsman argument, as “trollism” is something clearly different from criticism or even informal reviews.

Lots of people complain about critics (usually because the latest Michael Bay movie got a bad Rotten Tomatoes score) but it’s a different discussion.

Here, it seems to me he was careful enough to show meanness/vitriol in each of the “haters” portrayed so as to clearly define his target. Not those who criticize, but those who maliciously shoot their mouth.

Interesting that Noah finds Dan Clowes’ portrait of a self-involved internet critic in the story “Justin M. Damiano” “simple-minded and silly” but he’s pleased with this fascist retread of Ghostbusters 2.

I thought your reading was simple-minded and silly, not Clowes’ piece.

I feel like I should donate to some sort of center for recovering internet obsessives every time you post to remind me that you love Clowes and hate how I’ve wronged him, deelish.

““trollism” is something clearly different from criticism or even informal reviews.”

According to whom?

Showing that your antagonists are hateful isn’t a sign of nuance or discrimination. It’s just being hateful (not that that’s a bad thing.)

A critic can troll. A troll can criticize. But criticizing is not the same as trolling. Yes, I checked the dictionary.

But, oh well, for the group of people that consider trollism to be the same as criticism, yes, this analysis could eventually make some fine points. I guess.

Guys, please, there’s no need for angry rhetoric! I see where Noah is coming from. The comic is much more inventive than Zen Pencils’ usual inspirational drivel, and reading the text oppositionally, I can see why you would find it fascinating. I don’t agree that this makes the comic ‘good’ (obviously, since I wrote the article), but I understand why it’s important to approach it from multiple perspectives. Let’s not accuse each other of implicit fascism for comic opinions…

Pedro, I think you’re trolling now.

Patrick, you are not trolling sufficiently. More hate, damn it.

This strip has less cloying vacuousness than his other ones, it’s more of an embarrassing diatribe. But it shares with most of them that wonder (or dread) one feels at just how far he’s willing to take his interpretation of whatever out-of-context quote he’s working with.

My admittedly not precise or eloquent attempts to describe Clowes’ actual comic are simple and silly while the piece I was responding to, a puerile effort to turn the artist’s criticism of internet pundits back on him, is treated with chin-stroking seriousness, and now a comic that represents negativity as a green slime monster is hailed as “weird and imaginative”. Noah, when you forget to act like Gary Groth with a concussion your tastes seem to be of the unicorns and rainbows variety. Come to think of it, Dan Clowes’ comic “The Christian Astronauts” was a nice riposte to the brain-scrubbing cult of positive thinking evident in this person’s work.

Deelish, your negativity is harshing my mellow. Careful or green slime will explode from your orifices.

“Trolling” has become kind of a meaningless term, hasn’t it? It supposedly means expressing opinions that you don’t really hold just to upset people, but it’s more often used to describe expressing opinions that your audience doesn’t hold (like saying that Republicans are jerks on a right-wing site, for example). I see the same thing with “mansplaining”–it’s supposed to describe a guy telling a woman something that she already knew, but many feminist bloggers use it to mean any opinion expressed by a guy that they don’t share and/or find pompous.

As someone who has been accused of mansplaining a time or two (and basically like a hundred times yesterday), I would stick up for the word’s utility. Trolling as a term is useless, though.

I think trolling and mansplaining as terms have equal utility.

Your “mansplaining” moment does reveal that female romance fandom isn’t that different from male superhero (comics?) fandom. Who would have thought…

I’m also curious why Daphne Du Maurier isn’t inducted more often into the “romance canon.” I understand she hated being labeled as such but so what.

There are definitely some similarities. This probably isn’t really the thread to talk about it though…don’t want to derail Patrick’s post.

Did anyone else read this essay on snark vs. smarm?

http://gawker.com/on-smarm-1476594977

Here’s a quote:

“What is smarm, exactly? Smarm is a kind of performance—an assumption of the forms of seriousness, of virtue, of constructiveness, without the substance. Smarm is concerned with appropriateness and with tone. Smarm disapproves.

Smarm would rather talk about anything other than smarm. Why, smarm asks, can’t everyone just be nicer?”

The problem with the Zen Pencils comic is that he doesn’t seem to make any distinction between criticism and snark, critics and haters, etc. Basically, it’s just mad because someone peed on the happiness parade, or had the temerity to suggest that out of context inspirational quotes might not be what society needs right now.

Pingback: Kibbles ‘n’ Bits 4/27/14: People said things, did things — The Beat

Pingback: Kibbles ‘n’ Bits 4/27/14: People said things, did things | ComicBookRAW