My favorite sandwich as a teenager was named after an Alexander Dumas hero. I still order it at the Greek diner down the street, preferably with curly fries. You take your basic grilled ham and cheese, throw in a couple turkey slices, dunk it in egg batter, and fry, and be sure to have some jam sauce for dipping.

Restaurant reviewer Thadius Van Landingham declares it “a sandwich engulfed in controversy” and “clouded origins.” Some say it’s just a disguised croque monsieur (literally “Mr. Crunch”) served in Paris cafes since 1910. Faux New Orleans restaurants in Disneyland have featured it since 1966 (the year I was born), but the recipe had been wandering American cookbooks since the 30s—though under different aliases. San Francisco and San Diego both claim the monte cristo unmasked in their restaurants first, but L.A. offers a more likely origin story, either at the Brown Derby or Gordon’s, since both catered to the Hollywood crowd. The Son of Monte Cristo, sequel to The Count of Monte Cristo, premiered in 1940, and the rechristened Mr. Crunch debuted on the Gordon’s menu in 1941—I’m guessing as an advertising gimmick.

The monte cristo does not appear in Alexander Dumas’ Great Dictionary of Cuisine, his posthumous masterwork. “Novelist or cook,” wrote an early admirer, “Dumas is a master, and the two vocations appear to go hand in hand, or, rather, to be joined in one.” His bacon roties (“toasties”) may be a relative of the monte cristo (“Dice a pound of bacon and a slice of ham. Dry out and drain. Mix with parsley, scallions, 4 egg yolks, coarse pepper. Spread on slices of bread. fry.”), but a distant one.

Cookbooks annoy me because there’s usually only one author on the cover, while the work must require whole kitchen staffs of ghostwriters—plus all the uncredited friends and relatives and untold predecessors who knowingly or unknowingly contribute the first drafts of recipes. But Dumas’ culinary dictionary may be the only of his 200-300 books he wrote himself. Even his most famous novels were collaborations. A kitchen of hired assistants cooked up plots and pages for him to spice up and finalize to his tastes. Superman co-creator Joe Shuster employed a studio of artists to similar effect. Auguste Maquet, Dumas’ most prominent sous-chef de aventure, worked for him through the 1840s, unofficially co-authoring both The Count of Monte Cristo and The Three Musketeers. Bob Kane claimed similarly sole authorship of Batman because writer Bill Finger received his paychecks from him not DC. Maquet sued, but the French courts preferred Dumas’s lone wolf tale. Finger (a prolific plagiarist himself) stayed in the kitchen. Neither Dumas nor Kane served up anything of much flavor without their collaborators.

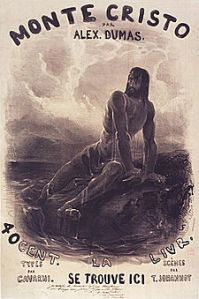

But The Count of Monte Cristo continues to be served across genres. If Maquet was the plotter, then he mixed both the first convicted-of-a-crime-he-didn’t-commit and revenge-is-best-served-cold recipes. They’re massive chapters in any contemporary dictionnaire de aventure, spanning in comics from Batman to V for Vendetta to Oldboy manga. The framed fugitive Edmond Dantès is also literature’s first secret identity hero and chameleon-like master-of-disguise. Like “Alexander Dumas” on the cover, the Count is only the first ingredient in a tossed salad of Dantès’ aliases, ranging from priest to bank clerk to Sinbad the Sailor. Also, like a comic book, the novel wasn’t a novel—it was a serial, published in eighteen monthly installments beginning in 1844. It was already an international hit when the Count jumped the channel into English two years later.

Dumas was a bit of mixed salad himself. His mother was “mulatto,” a fact he defended with wit against his few French detractors. In the U.S., even abolitionists had trouble believing a black man could produce Literature, thinking Frederick Douglass’ editors ghosted his 1845 Narrative of the Life. The last U.S. Presidential election had turned on Polk’s determination to annex Texas as a slave state. France vacillated on slavery, abolishing it for the first time in 1794 (“all men, irrespective of colour, living in the colonies are French citizens and will enjoy all the rights provided by the Constitution”—essentially the opposite of the U.S. Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision), and again while The Count of Monte Cristo was sailing to American book stores—where it would sellout despite its clouded origins.

I imagine it was Dumas, not Maquet, who decided the Count would marry Haydée, the Turkish princess he bought from a slave trader. Louis Hayward, star of The Son of Monte Cristo, doesn’t look particularly mixed, but that’s a U.S. film (and, according to the synopsis, he’s not actually their son anyway). I’ve been dipping into French comics recently (in preparation for my June visit), and have been pleasantly startled by some racial differences. Tarou, Robert Dansler’s 1949 Tarzan knock-off, is, unlike Burrough’s eugenically thoroughbred aristocrat Lord Greystoke, half African, and better still, Mozam is an “African Jungle Lord” drawn non-racistly African (though I fear “mozam” may literally be “nonsense”).

The Count, who’s taken for French, Arab, Roman and Greek, claims no nation and no race. “I am,” he declares, “a cosmopolite.” His shapeshifting ability to “adopt all customs, speak all languages” is a product of his mixed nature, elevating him to the superhuman level of angels, those “invisible beings” whom God sometimes allows “to assume a material form.” The only significant obstacle to his goals is his mortality, “for all the rest I have reduced to mathematical terms. What men call the chances of fate—namely, ruin, change, circumstances—I have fully anticipated, and if any of these should overtake me, yet it will not overwhelm me. Unless I die, I shall always be what I am.”

The monte cristo, declares Van Landingham, “is a jumble of contradictions,” both sweet and savory, a sugary breakfast yet a meaty lunch. It’s a fitting tribute to the contradictory Mr. Dumas and his hero. I look forward to searching Paris menus for both the Count and his alter ego Mr. Crunch.

href=”http://thepatronsaintofsuperheroes.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/monte-cristo-sandwich.jpg”>

Typo alert: Douglass wrote in 1845, not 1945.

If the monte cristo sandwich is based on the croque-monsieur, note that the latter is derived from the English welsh rabbit.

Another Monte Cristo: the cigar:

https://www.google.com/search?hl=FR&site=imghp&tbm=isch&source=hp&biw=1280&bih=913&q=monte+cristo+cigare&oq=monte+cristo+cig&gs_l=img.1.0.0j0i24.3667.13363.0.16425.16.12.0.4.4.0.86.662.12.12.0….0…1ac.1.46.img..0.16.678.NNGzUWUI8KQ&gws_rd=ssl

What, 1945 sound a little late for Douglass?

I’d fix it but I’m having some trouble logging in via the wireless of the 17th century Paris apartment my family and I just settled into. We’re about four blocks from Notre Dame and are violently jeglagged from the redeye flight. The street is a food lover’s dream. But no sign of Mr. Crunch yet.

I’ll fix it; no worries.

Actually Alexander Dumas mother was White. His father was black and also General of the Republic, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas-Alexandre_Dumas

There is the theory, that Dumas modeled the Count after his father.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Black_Count:_Glory,_Revolution,_Betrayal,_and_the_Real_Count_of_Monte_Cristo

Quite right, Frank. His father was mixed Haitian, and so it was Dumas’ grandmother I must have meant. (I would blame it on jetlag, but I drafted this before I left the states, so really I have no excuse.)

It’s worth pointing out that Dumas was proud of his Black roots, in fact boastful.

The same can be said of his near-contemporary,the Russian writer Alexander Pushkin…whose Black forebear was also a general. Hmm, I wonder if those two Black warriors ever faced each other on the battlefield?

Unfortunately, as a Parisian I’d never heard of the Monte Cristo sandwich before reading this. You should have no trouble finding a Croque Monsieur in Paris though, or a Croque Madame (Erich is a Croquet Monsieur with an egg on top, so probably closer to your Monte Cristi).

Yes, I did indeed find one in a St. Germain café earlier this week. Basically a toasted ham and cheese, so I’ll get the Madame version next time.