The list of superhero movies made since the 1978 Superman continues to grow exponentially, but I try to give a quick visual nod to each while lecturing in my Superhero course. After class a student told me I made the same remark three times:

“I never saw this, but I hear it’s terrible.”

There’s nothing so pleasantly humbling as a student spotting my professorial shortcomings. I make no apology for not seeing EVERY superhero film in existence, but the three I dismissed—Supergirl (1984), Cat Woman (2004), and Elektra (2005)—all feature female protagonists. In fact, my student noted, they are the ONLY superhero films to feature female protagonists on my list. I could blame Hollywood (is it really that hard to make a Wonder Woman movie?), but as a belated apology, let me offer a corrective instead.

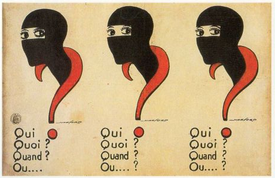

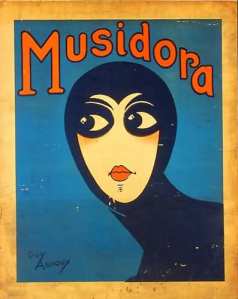

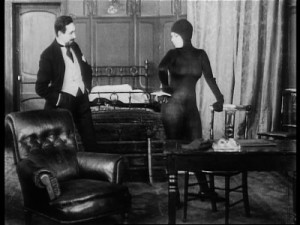

I have seen and thoroughly recommend cinemas’ first catwoman. Not Halle Berry or Michelle Pfeiffer—not even Lee Meriweather from the 1966 Batman spoof. The original bodysuited catburglar padded across screens a century ago. Silent age actress Musidora played the anti-heroine Irma Vep in Louis Feuillade’s seven-hour serial Les Vampires back in 1915.

Vep (her name’s an anagram) is not a vampire of the blood-sucking variety but the leading member of a crime syndicate terrorizing Paris. Technically Philipe Guérande, the “star reporter” investigating the Vampires, is the serial’s hero, but after debuting in the third episode, Vep dominates. She’s the Vampires’ second in command, out living each of the four Grand Vampires she works beside. They all have their nefarious skill sets—disguise, poisons, paralysis glove, hypnotic eyes, even a retractable cannon fired from an apartment window—but none are as memorable as Musidora in a black bodysuit. She has a bit of the shapeshifting Mystique in her too, since she assumes the identities of her aristocratic victims so seamlessly. She and her Vampires also push the limits of early twentieth century technology, recording a millionaire’s voice on a wax cylinder and playing it over a telephone to authenticate a forged check.

But they’re not thrill-seeking pranksters. Episode one opens with the report of a police inspector’s decapitated body found in a swamp. Thirty minutes later, Philipe is opening a box with the missing head. Vep and her crew later dispatch a businessman with a hair pin through the back of his skull then shuck his body from a moving train. They murder a ballerina because she’s rumored to be Philipe’s fiancé. They also have a knack for lassoing nooses around people’s necks and yanking them from balconies.

But the image that most haunts me is the ball thrown by a baron for his niece—really the Grand Vampire and Vep in disguise. The Parisian aristocracy gathers for the baron’s midnight “surprise” to find the windows boarded and toxic gas flooding through the vents. Feuillade’s camera is more stationary than many silent film directors’, but he’s a master of deep focus, staging a cascade of background and foreground action within a continuous frame. The gowned and tuxedoed guest flail and wilt across furniture and floors in a tableau of slaughter—followed by the silhouetted Vampires entering through a pair of backlit doors in the distant wall to plunder their jewels. When the police tear the planks from the windows the next morning, the guests miraculously revive (contradicting the verb “asphyxiate” in the translated intertitles).

Despite the mayhem, Feuillade seems to be rooting for Vep. When Philipe and his comic sidekick capture Vep, she looks like a classic damsel-in-distress. If you watched episode nine out of sequence, you would mistake her for the heroine, valiantly struggling against her kidnappers. In fact, Vep, more than all the plundered jewels and bank accounts, is the serial’s prize. The first and second Grand Vampires battle against the rival criminal Moreno not just for control of Paris but of Vep. Moreno falls for her, hypnotizes her into loving him, and next she’s gunning down her former boss. When the captured Moreno is executed between episodes (I suspect the actor was called away on war duty), the next Grand Vampire, Venomous, proposes.

Philipe’s wedding (Feulliade, apparently filming on the fly, introduces his fiancé with equal haste) occurs between episodes, but the final, “The Terrible Wedding,” features the Vampires in rambunctious celebration (I rewound the bodysuited dance duet to watch twice). Again, if watched out of sequence, the gangs looks like a fun-loving pack of pals—until Philipe and the police break in and gun them down. Some scramble for the balcony, but Philipe has sawed the floor so they plunge to the cement below where they writhe and die. It’s a surprisingly brutal ending. Only Vep escapes, sneaking to the basement where the heroes’ captured brides are imprisoned. But Philipe has already lowered a gun to them, and his wife shoots Vep dead just before the heroes enter, embracing their wives before Vep’s corpse. The End.

Feulliade may have been shooting for gritty realism (Paris had recently suffered the reign of the very real Bonnot Gang), but the accumulative effect is surrealism. He also established a host of action tropes still being duplicated— a chase atop a moving train, a hero yelling “Follow that cab!” as he leaps into a backseat, a bad guy swallowing a hidden cyanide capsule, and (since the capsule only induced a temporary comma) a prison break.

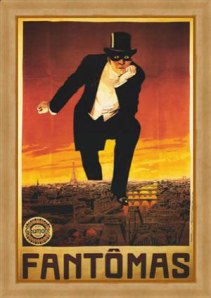

Feulliade had ventured into crime serials with Fantomos the year before, but Les Vampires inspired him further, shooting with the same cast for Judex and The New Mission of Judex. The effect is further dizzying, since it’s Musidora, not the titular hero, in the opening scene. Despite the name change, Vep is back, plotting more impersonations and seducing Santanas, the second Grand Vampire—only now he’s some evil banker. Philipe’s been demoted to the hero’s extraneous brother, but his comic sidekick is front and center as a bumbling detective, the proto-Clouseau. It’s like watching the latest Joss Whedon production, waiting to see which Buffy or Firefly or Dollhouse actor is going to appear next.

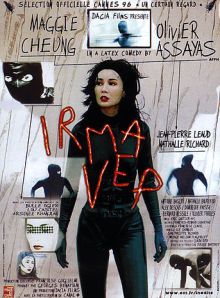

Despite hiring a playwright to give Judex relative continuity, Feulliade repeats a few of his Vampire tricks—like throwing a sack over a good guy’s head so when he switches bodies and escapes the bad guys murder one of their own. Sadly when Musidora’s body washes ashore in the final episode, Feulliade doesn’t reprise her for the sequel—so maybe it’s just as well all the prints are lost. The closest we have to a Les Vampires remake is fellow French director Olivier Assayas’ 1996 Irma Vep—a meta-film about the making of a remake (which I also recommend). So pay attention Hollywood. Cinema’s original supervillainess is waiting for her reboot.