This is part of a roundtable on the work of Octavia Butler. The index to the roundtable is here.

__________

How do critiques of identification complicate Western models of empathy? What might empathy look like, and produce, when it doesn’t require identification? What about more difficult cases in which the reader is required to empathize with the oppressor, or with more complicated protagonists? – Megan Boler, “The Risks of Empathy”

She was not afraid. She had gotten over being frightened by “ugly” faces long before her capture. The unknown frightened her. The cage she was in frightened her. She preferred becoming accustomed to any number of ugly faces to remaining in her cage. – Octavia Butler, Dawn

I didn’t agree to participate in this roundtable on Octavia Butler because I enjoy her writing, but rather because I don’t. My admiration for her storytelling is nothing short of begrudging; I have to work at it. And I’ve always been careful to attribute my resistance to matters of personal taste. Butler is, after all, a beloved award-winning writer in science fiction, a pioneer who helped open a space for communities of black speculative fiction writers that I adore, including Nnedi Okorafor, N.K. Jemison, Tannarive Due, and Zetta Elliot. So if I find the slug-like aliens in Dawn nauseating or if the pedophilic undertones in Fledgling nearly keep me from finishing the novel, then I assume that’s my problem.

My displeasure doesn’t prevent me from recognizing Butler’s importance in my African American literature courses and I teach her fiction whenever I can, with her 1979 novel Kindred being the most popular. Students are eager to embrace the story’s invitation to see the interconnected perils of slave resistance and survival through Dana’s modern eyes, grateful that the narrative’s historical corrective comes at the comfortable distance of science fiction tropes. The book raises provocative questions for debate, although I admit to being troubled by how often readers come away from Kindred convinced that they now know what it was like to be enslaved. Too often, their experience with the text is cushioned by what Megan Boler characterizes as “passive empathy”: “an untroubled identification that [does] not create estrangement or unfamiliarity. Rather, passive empathy [allows] them familiarity, ‘insight’ and ‘clear imagination’ of historical occurrences – and finally, a cathartic, innocent, and I would argue voyeuristic sense of closure (266).

Much of Butler’s fiction doesn’t work this way, however. Estrangement and unfamiliarity, particularly in relation to ugliness and the repulsiveness of the alien body, are central to her work. And this is what gets me. The non-human creatures she imagines make me cringe and their relationships with humans in her fiction are even harder to stomach. My first reaction to the Tlic race in Butler’s 1984 short story, “Bloodchild,” was disgust, made all the more unnerving because of the great care Butler seemed to take in the description of the strange species; the serpentine movements of their long, segmented bodies resemble giant worms with rows of limbs and insect-like stingers.

It doesn’t matter to me that the Tlic can speak English and feel pleasure and build governing institutions, not when they look like that. In the story, they use humans of both sexes to procreate in what initially appears to be a mutually beneficial, parasitic relationship, at least until the main character, a young human male named Gan, begins to question the status quo. Butler’s description of Gan curled up alongside T’Gatoi, the Tlic who has adopted him and his family, is not really an image I want to grapple with for long:

T’Gatoi and my mother had been friends all my mother’s life, and T’Gatoi was not interested in being honored in the house she considered her second home. She simply came in, climbed onto one of her special couches, and called me over to keep her warm. It was impossible to be formal with her while lying against her and hearing her complain as usual that I was too skinny.

“You’re better,” she said this time, probing me with six or seven of her limbs. “You’re gaining weight finally. Thinness is dangerous.” The probing changed subtly, became a series of caresses. (4)

T’Gatoi uses her authority as a government official to protect humans (called Terrans) in exchange for the use of their bodies as reproductive hosts. The balance of power between the two species tips back and forth in the interest of self-preservation and free will. Gan isn’t sure he wants to be impregnated – is he a partner or a pet? – but he ultimately submits under the terms of a negotiated relationship that takes into account both his discomfort with the T’Gatoi’s rules and his reluctant longing for her affection. T’Gatoi, too, has desires and cares for Gan. She also wants her Tlic children nurtured in a loving home if they are to survive. And while I admit that I can relate to these feelings and conflicted needs, this is a kind of intimacy that I’m willing to share with a pregnant man, not with a bug.*

Boler asserts that Western models of empathy are based on acts of “consuming” or universalizing differences so that the Other can be judged worthy of our compassion. Despite our best efforts, we end up using the Other “as a catalyst or a substitute” for ourselves in order to ease our own fears and vulnerabilities, rather than actively working to change the assumptions that shape our perspective (268). I’m in awe, then, of the way Butler’s science fiction heightens readers’ physical discomfort with characters like the Tlic in order to rebuff passive empathy and other modes of identification that absolve us of the need for critical self-reflection. T’Gatoi is the Other that I can never fully know. I can’t easily reduce her experience to my own, but I also can’t deny the prickle of recognition that comes from the emotional struggle between the Tlic and the Terrans. When Gan’s mother jokes, “I should have stepped on you when you were small enough,” I recognize her bitterness as a survival strategy, an attempt to upset a social hierarchy and dissociate from the Not Me.

So when I recoil at every reminder of T’Gatoi’s “ugliness,” I wonder what this emotion says about my approach to difference in society and in myself. How does my reaction to the unfamiliar outside the story, my unwillingness to engage the socially embodied strangeness of 2014, compare to the blustery panic of creepy crawly things I want to step on because they are small enough? (And what about those times when the bug is me?)

“Bloodchild” turns my personal readerly aversion into an ideological dilemma and advances the more challenging work of what Boler describes as “testimonial reading”:

Recognizing my position as ‘judge’ granted through the reading privilege, I must learn to question the genealogy of any particular emotional response: my scorn, my evaluation of others’ behaviour as good or bad, my irritation – each provides a site for interrogation of how the text challenges my investments in familiar cultural values. As I examine the history of a particular emotion, I can identify the taken-for-granted social values and structures of my own historical moment which mirror those encountered by the protagonist. Testimonial reading pushes us to recognize that a novel or biography reflects not merely a distant other, but analogous social relations in our own environment, in which our economic and social positions are implicated. (266-7)

Boler’s work on emotion and reading practices draws on her experience teaching Art Spiegelman’s Maus and other fictional works about historical events to make her case. But Butler’s science fiction thought-experiments also provide a framework for a mode of bearing witness that is just as complicated .

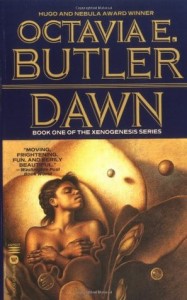

In the 1987 novel, Dawn, the first book of Butler’s Xenogenesis Trilogy (retitled Lilith’s Brood), the main character models the task of testimonial reading against the “affective obstacles” that hinder awareness of “the power relations guiding her response and judgments” (265). These obstacles initially come in the form of extraterrestrials called the Oankali whose bodies are entirely covered with writhing, grayish-white sensory tentacles. They have rescued groups of human survivors, including a black woman named Lilith, in the wake of nuclear destruction on Earth. Awakened on their ship years later, Lilith is required to remaining in her room with one of the ugly creatures until she can look at them without panic. The aliens know that before Lilith can interact with their society without harming herself or others, she must grapple with her revulsion at their physical appearance:

[The Oankali] walked across the room to the table platform, put one many-fingered hand on it, and boosted himself up. Legs drawn against his body, he walked easily on his hands to the center of the platform. The whole series of movements was so fluid and natural, yet so alien that it fascinated her.

Abruptly she realized he was several feet closer to her. She leaped away. Then, feeling utterly foolish, she tried to come back. …

“I don’t understand why I’m so… afraid of you,” she whispered. “Of the way you look, I mean. You’re not that different. There are – or were – life forms on Earth that looked a little like you.”

He said nothing.

She looked at him sharply, fearing he had fallen into one of his long silences. “Is it something you’re doing?” she demanded, “something I don’t know about?”

“I’m here to teach you to be comfortable with us,” he said. “You’re doing very well.”

She did not feel she was doing well at all. “What have others done?”

“Several have tried to kill me.”

She swallowed. It amazed her that they had been able to bring themselves to touch him. “What did you do to them?

“For trying to kill me?”

“No, before – to incite them.”

“No more than I’m doing to you now.” (16-17)

Entire chapters are spent detailing the process through which Lilith learns to view the Oankali named Jdahya without fear. Their exchange invites comparisons with the xenophobia and prejudice of our own world, of course; Lilith’s dark skin could easily elicit similar reactions. Untangling the “genealogy” of her emotional responses becomes even more daunting once she learns that the aliens have three sexes and the ability to manipulate the genetic material of other beings. She is repulsed one moment, curious the next. Unable to look away, she demands answers from Jdahya until her body’s refusal to accept what he is becomes physically and emotionally exhausting. It is then that she begins to ask questions of herself. “God, I’m so tired of this… Why can’t I stop it?” (26).

Butler turns Lilith’s reactionary apprehension into a more productive space for her and for us as readers so that we may all think more critically about the larger forces at work in our judgments of others. To me this is what makes Butler an exceptional storyteller, whether I like her writing or not. Equally important is the fact that Lilith’s encounter with this single Oankali is only a first step. She’ll have to leave the room, meet others, apply what she has learned. For my own part, I’m now half way through Adulthood Rites, the second book in Lilith’s Brood and it is slow going, but I want to finish. The story has been difficult and deeply rewarding for me in a way that I’ve come to expect from Octavia Butler, a reading experience not unlike the probing of limbs that turns to a series of caresses.

*Nnedi Okorafor also explores dynamics of power through human companionship with an insect-like robot in her terrific short story, “Spider the Artist.”

Works Cited

Boler, Megan. “The Risks of Empathy: Interrogating Multiculturalism’s Gaze.” Cultural Studies. 11 (2) 1997: 253-73.

Butler, Octavia. Bloodchild and Other Stories. New York: Seven Stories Press, 1996.

—–. Lilith’s Brood: Dawn, Adulthood Rites, and Imago. New York: Warner Books, 2000.

“The non-human creatures she imagines make me cringe and their relationships with humans in her fiction are even harder to stomach.”

I think you’re right that difference in Butler is supposed to make folks recoil; she talks about how Bloodchild was inspired by her terror/loathing of blowflies.

At the same time…the fascination with tentacle sex, with alien sex, with sex with underage vampires…I don’t think it’s just supposed to be repulsive, or I don’t think Butler’s affect is just disgust. I mean, the books are often chronicles of kink, yes? There’s a huge audience for tentacle porn, for sex with monster porn, for vampire porn. And there’s a long tradition of sci-fi authors using the genre to explore their kinks (Samuel Delany most obviously, but also John Varley, Piers Anthony, Jack. L. Chalker, in film David Cronenberg — just lots of folks.)

this is scholarship at its best, qiana. wow. i love the way you invoke yourself and your own feelings (disgust, moral qualms, desire) in reading butler, especially given that butler doesn’t do it for you. i am always astonished when people say that butler doesn’t do it for them. i find her eye candy. i find that i can’t put her down. i read the lillith trilogy like i was reading a sacred text. i longed for the intense pleasure the oankali provided themselves and their humans. i longed for the connectedness. i felt ashamed of being human.

i guess that’s something that butler does for us, too. she makes us ashamed of being human.

i wish you good luck with finishing the lillith trilogy, and hope hope hope you’ll write more (and more) about butler, your discomfort, your returning to her over and over, your struggle with her writing, and difference.

Noah, I would agree with that, which is what I was hoping to allude to in the reference to T’Gatoi’s caress and Gan’s attraction. I could have also spent more time on how Lilith’s disgust gives way to sexual arousal… but I guess I was more interested in the first, knee-jerk reactions? But thinking about it more carefully now, I don’t believe that kinkiness completely displaces the discomfort, or at least the sense that something very taboo is happening. The two emotions can sit alongside one another (at least they do for me) and could still yield some interesting moments of personal reflection.

I will say that in the case of Fledgling, I absolutely did not – or rather, refused to allow myself – to admit to any feelings of pleasure/fascination. That book was very hard for me to deal with and I am grateful for the friends/scholars who have found productive ways to talk about what Butler is doing there.

Thanks, Gio! Eye candy, huh? There are a lot of writers that I find myself reading like sacred text, but Butler just doesn’t bring that out in me. Samuel Delany does, Morrison, Baldwin… Every time I admit my feelings about Butler, people make recommendations about what I should read next, so you’ll have to give me another suggestion.

the kinky is where the pleasure is. if you don’t enjoy at least *reading* about kinky sex you won’t enjoy butler — or most of her writing. for a queer person, butler is paradise.

Yeah; I think the technical term is “squick”, right? Kink is powered by disgust and disgust is powered by kink.

Fledgling seems like it might be usefully compared to Twilight in a lot of ways. Both use vampire stories as a way to explore pretty clearly erotic fascinations with pedophilia and incest.

“if you don’t enjoy at least *reading* about kinky sex you won’t enjoy butler.”

I think there’s a lot of truth to that…but I also get the sense that critics aren’t as tuned into that as they might be, or that it’s something that isn’t talked about a ton. I’ve certainly seen folks talk about how depressing she is or how pessimistic…and that’s a take that has to be seriously qualified if (for instance) the alien sex in Xenogenesis is seen as a pleasure in itself for readers.

The extent to which Delany’s work is fueled by his kink on the other hand seems fairly widely acknowledged. I’m not sure what the difference is; maybe that Delany situates himself more fully in the avant garde, so shocking the bourgeoisie fits more easily into people’s conception of him? Maybe that Butler is a woman?

Delany seems to have written a lot more about his own sexual identity as a gay male in addition to foregrounding these representations in his fiction. And doesn’t Butler emphasize human/alien sex in a way that is more crucial to the character development than to the plot? I haven’t really read enough to pose more than a few questions. I think you’re right, though, that critical conversations do not devote the same kind of attention to sexuality and pleasure in her work.

So, squick? I will have to use that…!

“And doesn’t Butler emphasize human/alien sex in a way that is more crucial to the character development than to the plot?”

I’m not exactly sure what you mean by this? Sex with aliens seems pretty central to the plot and themes of Dawn, Bloodchild, Fledgling…?

Hmmm…looking around, “squick” seems formally defined as just something that personally disgusts you. I feel like I’ve seen it paired with kink, but not seeing a definition that quite gets at that…

I think you’re right that Delany talked more about the way his erotic identity was involved in his fiction. Did Butler ever say, “alien sex is hot” at any point? She certainly doesn’t in the afterwords to the stories in Bloodchild…

This is an insightful essay and touches on something about Butler’s work that really resonates with me. Her work does alienate and that alienation is the point. The interlocking narratives that speak of desires (often dark and compelling) are vehicle for debates we cannot or will not permit in the public sphere. Butler’s stories do some much, it great to see your take.

Ah well, I was going to say that a work like “Bloodchild” is more interested in reproduction and power than sexual pleasure, but, eh… That’s not quite what I mean either. Just that there may be a different investment in pleasure as compared to Delany… I don’t recall Butler making any comments about aliens sex either, but now I’m curious enough to look through the book of her interviews.

I really appreciate that, Julian. Can’t wait to read your take!

I think Butler is more ambivalent about the kink than Delany is. There’s definitely sexual pleasure, and sexual jealousy, directed at the aliens in Bloodchild, though, I think.

“she makes us ashamed of being human.”

I had the sam reaction reading Dawn, though not for the same reasons as you, giovanna.

The hatred and the violence of the human characters just seemed so…believable. And the contrast with a gentle alien species that doesn’t understand that part of us at all. Of course, the Oankali are imprisoning and raping the humans, so they are also violent in their own way, but it’s not motivated by fear and hatred. It’s actually motivated by a desire to preserve life.

They preserve, we destroy. That’s what made me feel ashamed to be human.

That being ashamed to be human in Dawn though is also shame at being the colonized. The Oankali are the imperialists there; right? The civilized English bringing order and righteousness to the savages.

I’ve mentioned I love “Dawn”, right? For me it’s maybe her one truly great book.

I don’t think you have to feel like masturbating to enjoy the sexuality in these stories. I take cognitive pleasure in being grossed out and having my expectations manipulated. I have a worm phobia, so the “hair” in Xenogenesis really did me in.

I really enjoyed this essay. Colin McGinn has a book on disgust that defines the cause the emotion as a transgression of categories that, if I’m remembering rightly, largely have to do with life and death. Things representing death to us being mixed with something representing life to create a paradoxical living-undead sort of mixture is the crux of what really grosses us out. I’d say Butler is a master of that, such as her maggot birth scene in Bloodchild and aforementioned sex scenes in Xenogenesis.

Also, is it only me that pictured the T’Gatoi as being more lizard like than bug?

Thanks for the McGinn recommendation! http://www.amazon.com/The-Meaning-Disgust-McGinn-Colin/dp/B00DT669NY I’m going to have to check this out. While I was searching, I also found this book called “The Infested Mind” about human reactions to insects. Butler would have loved it, I’m sure: http://www.amazon.com/The-Infested-Mind-Humans-Insects

I saw T’Gatoi as kind of a centipede, given the multiple limbs and segments of her body? But then there is that tail with the stinger. Maybe like a long scorpion? Ugh.

“I take cognitive pleasure in being grossed out and having my expectations manipulated.”

I think the lines between cognitive pleasure, embodied sexual pleasure, and disgust are things that Butler is exploring or playing with. Oankali sex is basically psychic sex, right?

This is a great essay. It certainly would be fun to do a Kristeva reading of feminist Othering abjection in Butler– Kristeva has a great deal to say about the abject body of the mother and the social utility of abjection, but perhaps the most metaphysical moment is when she describes disgust as just the other side of unbounded and bodiless ecstasy.

Not sure how much of interest this will be, but I have a massive essay about tentacle sex, worm sex, zombie sex, and other such things here.

And google found me this essay on Kristeva, Xenogenesis, and Carpenter’s The Thing.

Fecund horror! I just started the essay, Noah, and I’ve bookmarked to finish later. I’ve never actually seen John Carpenter’s The Thing either.

Shame at being colonized…and internalizing the colonizer’s view of us?

By way of contrast perhaps, this reviews some pretty but fairly non-abject versions of black hybrid futurism in visual art: http://blog.art21.org/2014/06/24/black-futurism-the-creative-destruction-and-reconstruction-of-race-in-contemporary-art/#.U6sc9YUb1CZ

Matt, I think that’s at least one reading. The Oankali argue that humans are broken and irredeemable, pretty much, only useful/worthy to the extent that they can be cannibalized for parts by the Oankali. They actually make a good case…but I think Butler and the novel are aware that the case maps neatly onto colonial discourses.

“Oankali sex is basically psychic sex, right?”

Is it psychic sex if you have to plug in? Not sure about that one. Yeah, she complicates these things.

Pyschic-ish sex, anyway.

Definitely fetishy, too, since they need the Ooloi mediator to get off.

Something that above commenters didn’t really touch on in regards to kink and the enjoyment/discomfort thing (I think) is that that shame or discomfort can be part of the kink itself. That it’s not just about the alieniness or tentacle aspect, but the unease that comes with it that is equally as arousing.

You certainly hit on something, Kat. For some people, there’s pleasure in feeling uncomfortable. And Butler was a master at making us feel uncomfortable. Also, it forces introspection, which is exactly the purpose of testimonial reading. I really enjoyed this piece!

Thanks, Kat and Alisha!

I was also recently made away of this article by Rebecca Wanzo on “Apocalyptic Empathy: A Parable of Postmodern Sentimentality” but this one focuses on the Butler’s Parable series. Looks very interesting: http://pdc-connection.ebscohost.com/c/essays/21684196/apocalyptic-empathy-parable-postmodern-sentimentality

Thanks, Qiana! The Parable series is my favorite. I’ll check this out.

Thanks for this. I’d been preparing a lecture on empathy and was trying to noodle some different ways to express a point, and it sounds like the Boler article is just what I need to read. As was this. :)

I get that Butler’s not your thing, but I would recommend the Parable or Pattern books next — no physical/visual ugliness to deal with there, just the social ugliness of humankind. (The Parable books are later and better-written, IMO.)

Thanks for stopping by, N.K. – and for the suggestions! Will definitely check out the Pattern books, which I haven’t read yet. The Parable series proved to be very useful for me when I was doing some work on race and religion, and I agree that her writing in those books is much better.