Li Kunwu and Philippe Ôtié’s A Chinese Life is the kind of book I would normally resist reading; the chief reason being it’s overly familiar subject matter.

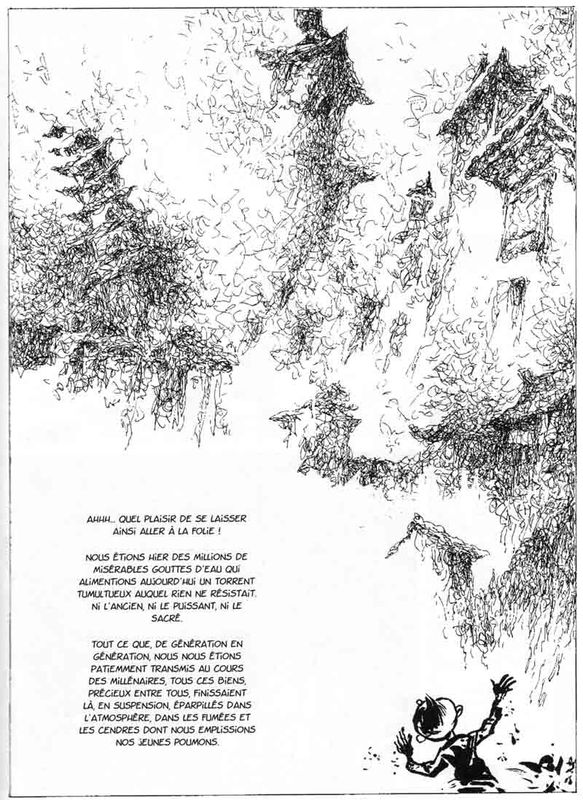

For a period during the 80-90s, it seemed almost impossible to escape the Cultural Revolution Industry. These were the scar dramas which followed in the footsteps of the scar literature; the subject de jour once Deng Xiaoping pronounced that period between 1966 to 1976 as being “ten years of catastrophe” (shinian haojie). As far as the Western sphere is concerned, one should not underestimate the effect the commercial success of works like Jung Chang’s Wild Swans had on this era. For Chinese writers and filmmakers who had stories to tell and willing publishers and financiers, the Cultural Revolution soon became ten years ripe for cultural monetization.

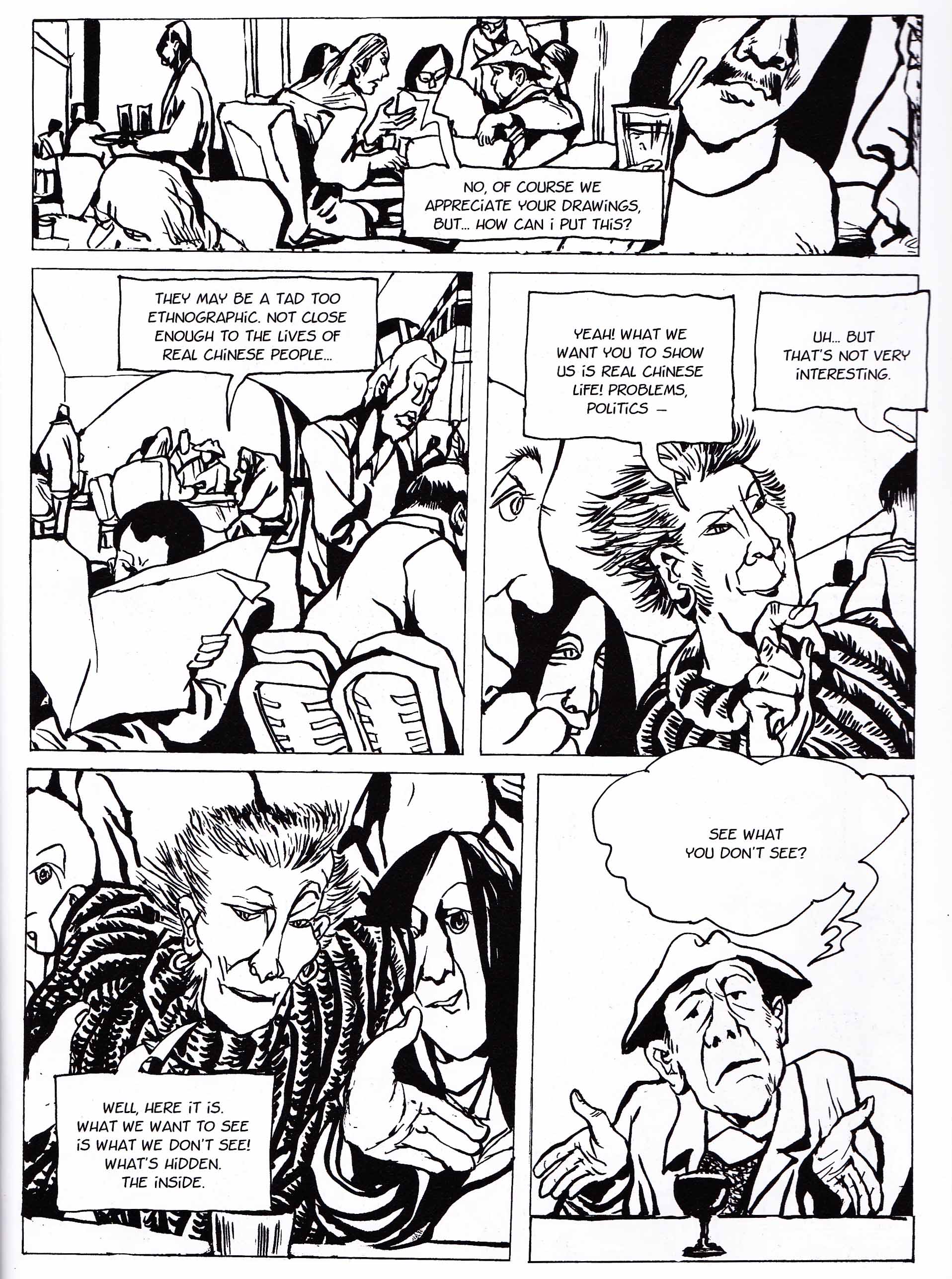

As far as Chinese contemporary art is concerned, a collector once laughingly told me that Chinese artists had discovered that the key to financial success was to make art which is “political.” Not an approach alien to the professional writer who understands full well that controversy sells, but here made more acute by the Western preoccupation with China’s political woes almost to the exclusion of all else (anyone read any non-political Chinese literature lately?).

The 2012 Nobel Literature prize winner, Mo Yan, presents us with the opposite side of the coin. The disgust with which some Western-based China watchers and dissidents greeted his elevation to the ranks of the literary “elite” was largely based on his poor politics and only secondarily his lack of literary merit. In short, he is perceived in some parts to be a party boot licker or at best a literary coward without a strong inclination to be exiled and imprisoned like a latter day Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn or, more precisely, the Nobel Peace laureate, Liu Xiaobo. Mo Yan’s novels are in fact frequently political but not in the way favored by Western journalists and academics. He is, in fact, the wrong kind of Chinese novelist.

A Chinese Life is a bit late to the party and passed with minimal notice in the year of its publication. Its contents would appear to be of a piece with the literature and movies which have inundated the West since the opening of the Chinese market. As a comic, it is solidly mediocre, the kind of “worthy” book some would point to if questioned concerning the suitability of comics for adults. It does gain some gravitas from its roots in autobiography but, as always, the failure here lies in the lack of narrative imagination and literary beauty—as history, it is far too shallow; as a work of literature, plodding and unemotive. It was, in short, an absolute chore to get through and ranks as one of the worst things I’ve encountered concerning China’s late 20th century history. The fault lies largely with Ôtié who fails to sculpt Li’s story into an engaging whole. All that remains is Li’s frequently interesting draftsmanship; he is a good artist undone by a poor storyteller.

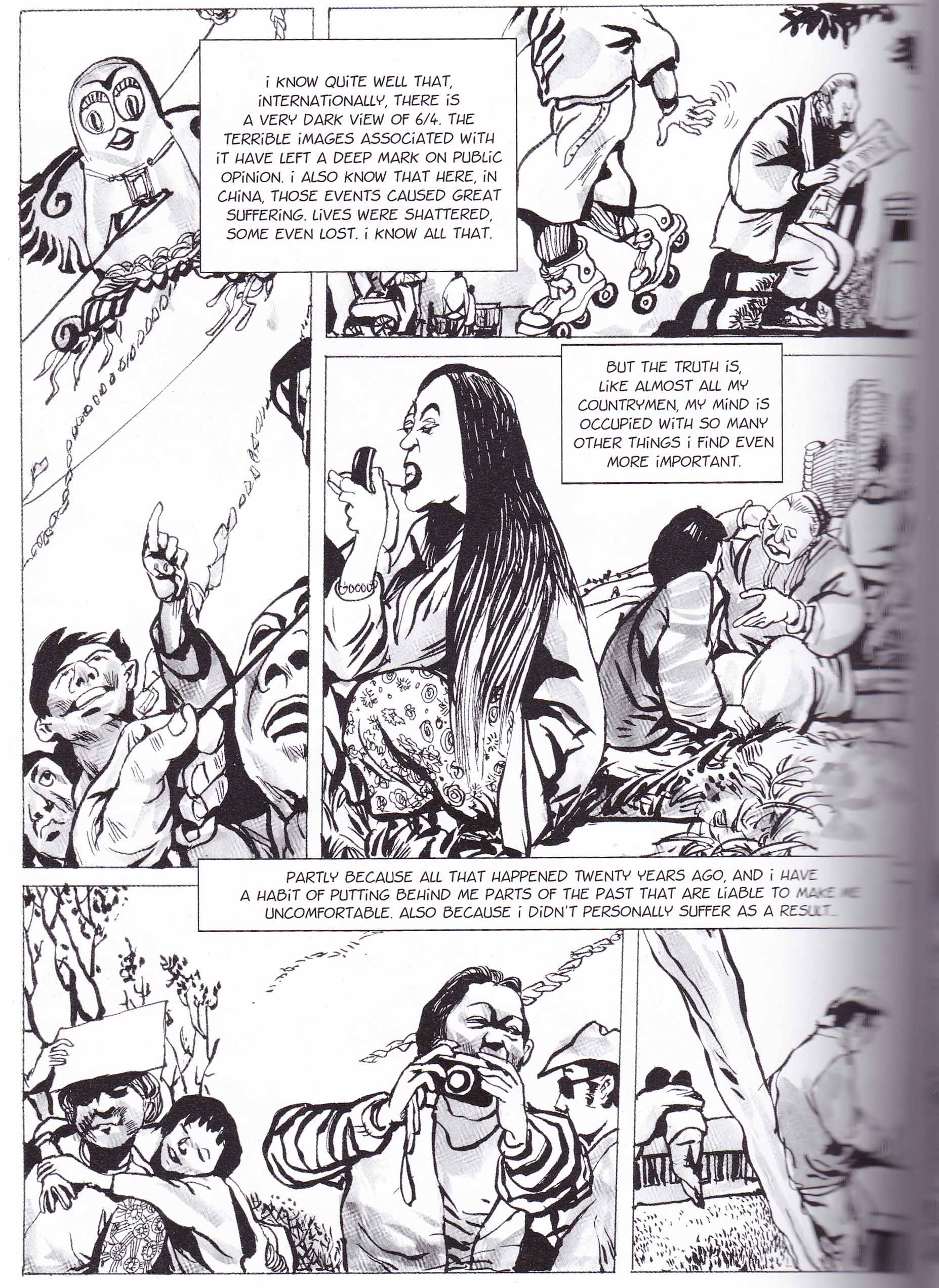

If a reviewer like Rob Clough is made to wonder whether A Chinese Life is propaganda, it is simply the result of the largely unexamined and uninterrogated life which fills these pages—an approach which informs not only the third and final book of A Chinese Life (the one concerning modern China) but, for all intents and purposes, its entire length. If there is one exception to this rule, it would be Li’s thoughts on the “6/4” incident.

So what made me borrow and read this book? Well, it was this snippet from a review by Rob Clough:

“The whole philosophy of the book is very much “the past is the past”…we once again go back to the Deng doctrine of “Development is our first priority”. As Li describes it, it’s the only priority.

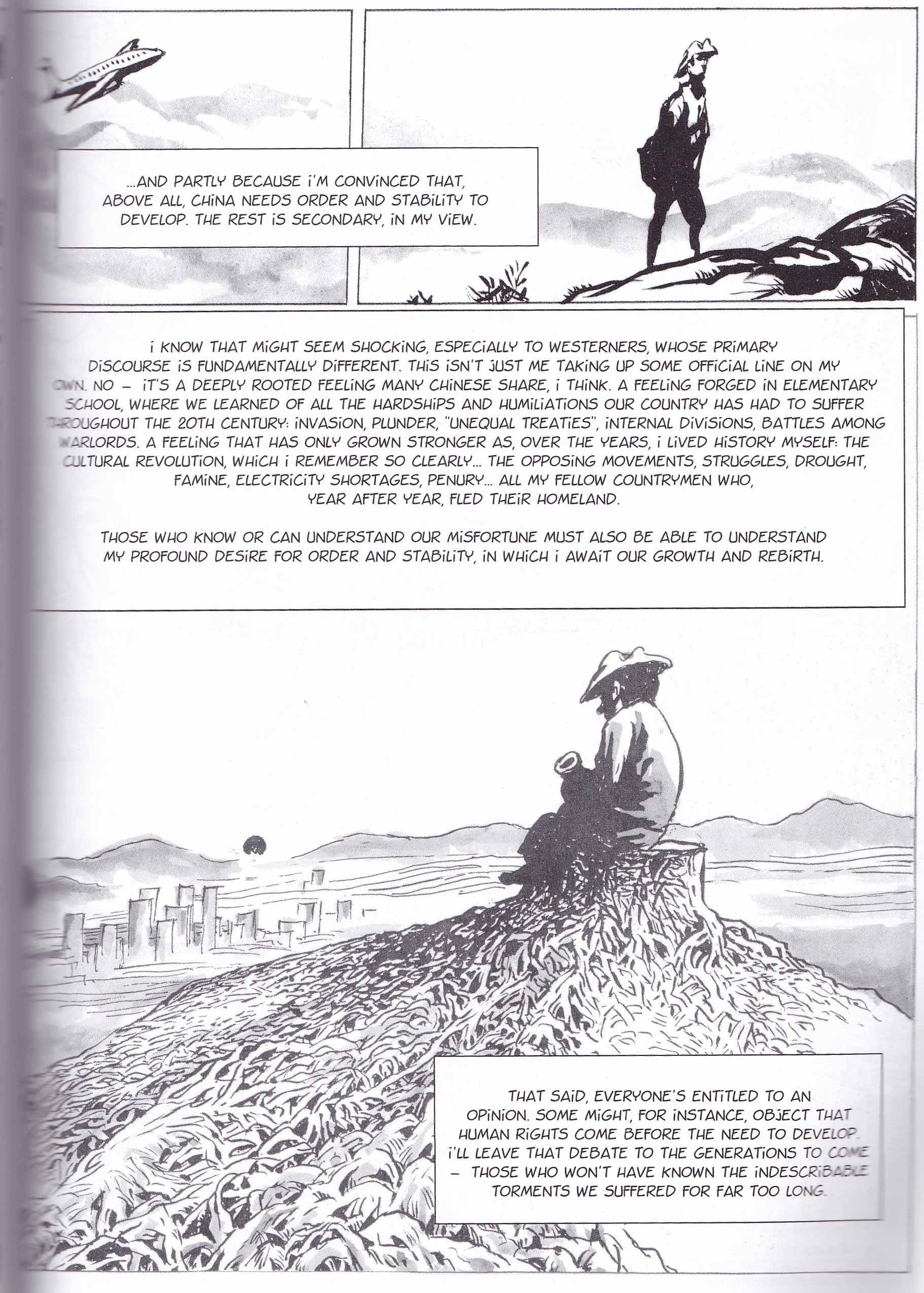

This leads to an interstitial scene where Li and Otie argue about how best to present his view on the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. Otie stresses to him the importance of this event to Western readers, and Li is resistant, because he said that he wasn’t anywhere near Beijing, only listened to the reports on the radio and has no idea what actually happened. Because he “didn’t personally suffer”, it wasn’t something that was really part of his story like the Cultural Revolution, Great Leap Forward…He notes that while he understands that lives were lost and people suffered, he considered the event within the context of Chinese history. Essentially, he was tired of China being a whipping boy for foreign interests and invaders. He was tired of instability. He was tired of being behind the industrialized nations of the world. The most salient quote is “China needs order and stability. The rest is secondary.” The past is the past. Development is the first priority.

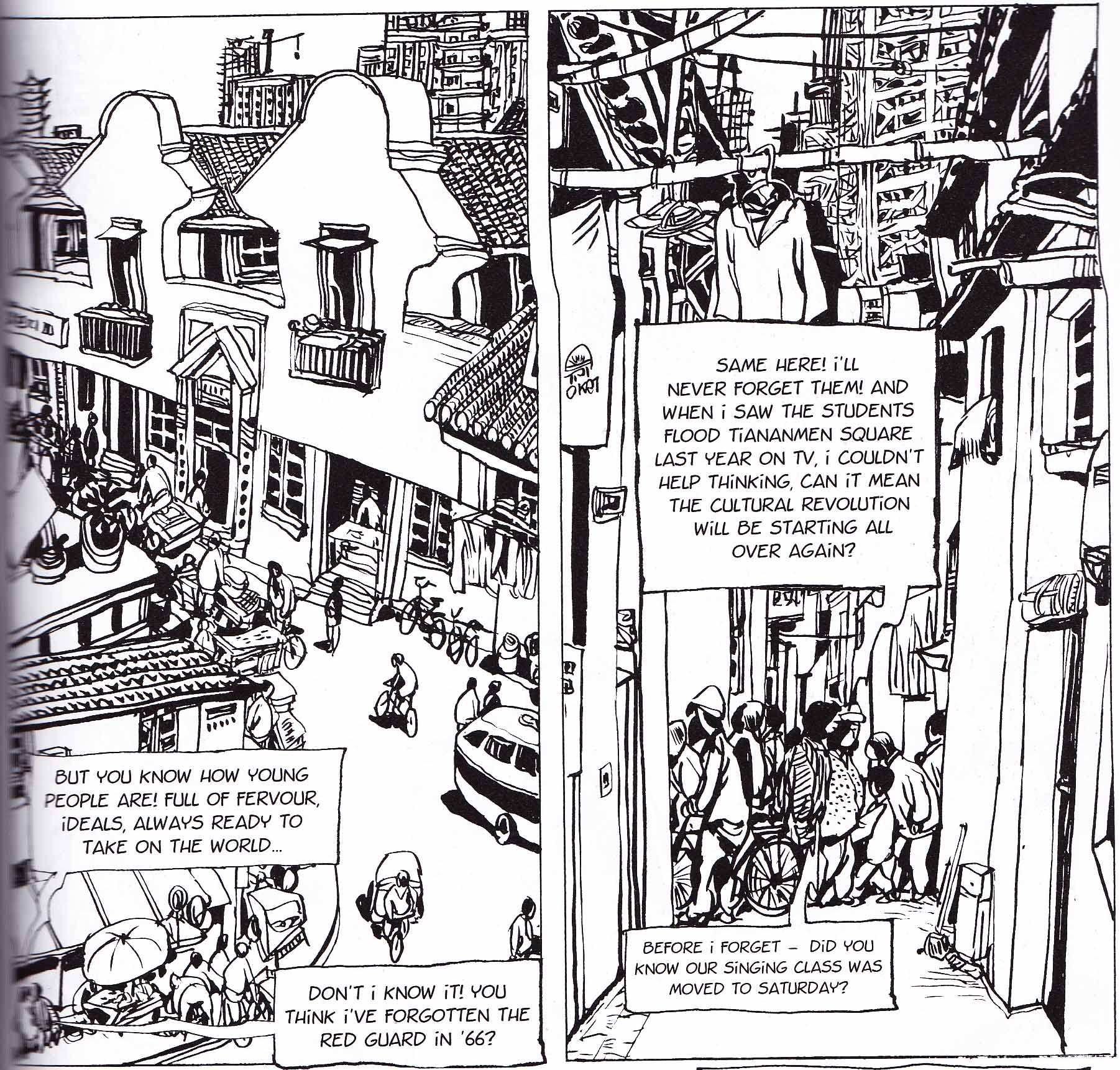

It’s a statement that makes a degree of sense within the context of a countryman who suffered during the prior youth revolution (indeed, some women in his story fear the events of the protests as the potential return of the Red Guard)…It is disappointing, however, to see an intelligent man like Li who fancies himself a moralist in rooting out corruption to simply toss aside human rights and freedoms as expendable when the corporate well-being of China is involved. It is a kind of moral compartmentalization that reeks of hypocrisy, the same kind of hypocrisy he faced (and was part of) during the Cultural Revolution. It values dogma (or progress) over humanity.” [emphasis mine]

But what exactly does a word like a “progress” mean to a person like Li? His words are sparse, his actual intentions up for conjecture. When Li indicates that, “China needs order and stability. The rest is secondary,” should we take his words as those of a coward, a hypocrite, or one with little respect for “humanity?” Can there in fact be any conception of human rights in a state without order and stability?

What can it mean for a man like Li to hear of distant reports of protesters being killed when the reports in earlier times had been those of war and cannibalism; the evidence before his eyes that of people dropping like flies by the wayside. The past clearly isn’t the past for Chinese citizens like Li. If anything, it thoroughly colors their perception of China’s present day fortunes.

Two other reviews online arrive at the same point as Clough in the course of their largely positive reviews:

“Li is far more a witness than a commentator. He declines to cover the events of Tiananmen Square because, he says, he wasn’t even there (but that scene with his co-writer Philippe Ôtié shows him wriggling apologetically to avoid it – it was obviously a bone of contention), and you won’t see Tibet mentioned once. He’s far prouder of what China has accomplished in thirty-five short years…” Stephen at Page 45

“Although this 60 year story largely ignores China’s fragile relationship with Taiwan and Tibet and only briefly mentions Tiananmen square, Li acknowledges these weaknesses by openly accepting that this is a story of his life, a single man, and no single man lives through all the history of his entire country (he didn’t know anyone affected by Tiananmen and therefore had little to say).” Hardly Written

The reviews which accompanied the publication of A Chinese Life seem more useful in revealing the differing attitudes of readers (presumably) from the West and the mainland Chinese; for Li’s attitude towards the Tiananmen demonstrations are hardly novel and have been ennunciated periodically over the years by the Chinese people. On the other hand, it is all too clear that the Tiananmen Massacre is one of the central prisms through which the West understands China, in much the same way the word “Africa” conjures up images of war, famine, and disease for the casual reader.

These reviewers would appear to be readers who have grown up in stable and ordered societies while Li has actually been one of those deluded and disappointed revolutionaries; one who has been recurrently attracted to mass movements. These experiences have clearly allowed him to entertain doubts concerning received notions of what is best for China and what human beings need first and foremost. And in this instance at least, ideology has come in second best.

Progress and human rights may not be mutually exclusive but it seems obvious that Li views the democracy movement and potential revolution of June Fourth as detrimental to the former and, as a consequence, to the latter. The prescription which America has recommended and administered to its client states has been political freedom (this word used loosely) before economic freedom, while Li clearly believes that the reverse is the surer course towards true liberty—patiently awaiting the creation of an educated middle class more attuned to the demands of a democratic system and who will, hopefully, make greater demands for political expression. Such has been the course for the former dictatorships in South Korea and Taiwan as well as the authoritarian democracy of Singapore.

What is the objective of political freedom if not the happiness of its people? For many Chinese today, mere sustenance, attaining a first world lifestyle (for all its ills), and the well being of their family members come before notions of a democratically elected government, especially when that tarnished model of democracy, the United States government seems effectively little better than the authoritarian one they are currently experiencing. The rampant capitalism which is America’s true essence, on the other hand, seems rather worth emulating; greed being altogether more attractive as far as human nature is concerned. Liu Xiaobo is a poor thinker when it comes to the history of the Western powers but he affords a somewhat different perspective when it comes to China’s economic “rise”:

“The main beneficiaries of the miracle have been the power elite; the benefits for ordinary people are more like the leftovers at a banquet table. The regime stresses a “right to survival” as the most important of human rights, but the purpose of this…is to serve the financial interest of the power elite and the political stability of the regime… […]…an autocratic regime has hijacked the minds of the Chinese populace and has channeled its patriotic sentiments into a nationalistic craze this is producing a widespread blindness, loss of reason, and obliteration of universal values…The result is our people are infatuated more and more with fabricated myths: they look only at the prosperous side of China’s rise, not at the side where destitution and deterioration are visible…” [emphasis mine]

A recent survey by researchers at the University of Michigan indicates that China’s Gini coefficient for income inequality could be as high as 0.55 having recently surpassed that of the United States. According to a report from Peking University, China’s Gini coefficient for wealth inequality comes in at 0.73 which is slightly lower than that of the U.S.. If there are lessons being learnt from the West, it would appear to be all the wrong ones. Consider the words of Liu Xiaobo in “On Living with Dignity in China” and see if they might not also be applied to the America we all know and love:

“In a totalitarian state, the purpose of politics is power and power alone. The “nation” and its peoples are mentioned only to give an air of legitimacy to the application of power. The people accept this devalued existence, asking only to live from day to day…This has remained a constant for the Chinese, duped in the past by Communist hyperbole; and bribed in the present with promises of peace and prosperity. All along they have subsisted in an inhuman wasteland.”

[I should note here that the 2013 BBC Country Rating Poll suggests that the citizens of China and the United States have equal amounts of antipathy towards each other.]

Given a choice between Mitt Romney and Barack Obama, the American public chose the lesser evil—the man who has delivered some change and only marginally more murder—the man with no moral center. It is not hard to see that Li might view his own choice in a similar light. And he is living with his choices as are the rest of the Chinese people. As I sit in the comfort of my home, in all my life not having suffered one day of hunger, repression, and fear as severe as those experienced by Li Kunwu through China’s turbulent 20th century, I am inclined to be more understanding and less judgmental.

The point about people mistrusting Tiananmen in light of the Cultural Revolution makes a lot of sense, but is something I’d never thought of.

On the other hand, I’ve been reading Richard J. Evans’ history of the Third Reich, and it’s hard to look at that and feel like choosing stability out of fear of violence leads good places (whether it’s China or the U.S. doing it.)

Isn’t that part of Li’s Faustian bargain? He chose stability and got an incredibly repressive regime which imprisons dissidents at will. Having said that, there must be thousands of unsanctioned mass protests in China every year for various causes. By that single metric, China is more free than the reasonably prosperous authoritarian democracy of Singapore where these are illegal (a permit is required).

The real lesson here is that we should mistrust anyone who tells us that political ideology is the key to economic development or transitioning from third/second world to first.

Li starts from a very different position from the average person living in the developed world. Based on his short narration, my take on the problem facing Li is this: What do you do if you find the demonstrators’ cause unworthy and ill thought out but at the same time find that the manner in which they were dealt with morally repugnant?

That the massacre was an act of evil (or at best a terrible mistake) has even been acknowledged by reformers within the party (both old and new). Yet the demonstrators were characterized by poor leadership, in-fighting (to this day as it happens – see the case of Chai Ling), and hubris. They were naive with regards the nature and practice of governance, had an inability to compromise, failed to give adequate backing to their supporters within the politburo, and their actions (for all their good intentions) probably set back the cause of human rights in China for years (perhaps decades).

Fair enough. It’s interesting that in terms of the Nazi takeover, it really was abetted in a lot of ways by the idiocy and viciousness of the Communists, who wouldn’t make common cause with others on the left. And of course the Bolshevik takeover in Russia where everyone but the Communists on the left was killed basically radicalized reactionary opinion throughout Europe in a lot of ways (as well as making German social democrats unwilling to ally with the Communists.)

The crux of what bugged me about Li’s book lies in the casual reference to how in elementary school Chinese children are indoctrinated in all the “wrongs” perpetrated against the populace. I say “indoctrination,” precisely because while it’s now okay to talk about the political machinations of the Cultural Revolution (because the parties involved are long since gone), Tiananmen, which threatened people currently in power, is officially censored. You can’t even use the date anymore, leading to the rather odd but telling construction of “May 35.” Li’s casual silence, whether he likes it or not, reflects on the official, the enforced silence[s] of the current regime. It strikes me as no mere coincidence that his book discusses what officially you’re allowed to and fails to discuss what officially you’re not allowed to.

Moreover, the “wrongs done to the Chinese people” demonstrates a remarkable lack of insight into the ways those wrongs are used by the party to deflect from their own missteps. They are more than willing to support protests and bus in students when the ire is directed toward the Japanese, who, admittedly, deserve the criticism, or some other bogeyman, but the second those protests turn back toward the regime, the powers that be step in immediately to make sure those students get back to where they came from.

Li may not have intended to be complicit in the official discourse of political opinions that are/are not permitted to be expressed, but the fact that what he does and does not treat so clearly reflects that discourse cannot simply be overlooked as “another kind of opinion.”

Yes, I get your point.

But in Li’s defense and on the basis of the comic, he doesn’t seem like much of a thinker. The story as a whole is a pretty basic oral history and I would not be surprised to find out that it was constructed largely out of audio interviews (with minimal tinkering). So its value lies in its common or garden perspective – the kind of perspective you would get if you spoke to the average mainland Chinese tourist of similar years and experience. The truth is most of them don’t think of 6/4 very much, no more than the average American thinks of the Korean War perhaps. They’re more concerned with present day realities.

On a side note, Li’s stories from the Mao years are sparse and anecdotal, offering very little insight beyond his specific (highly edited) experiences. This was an artistic decision and Otie should have fought it. So as one-stop Cultural Revolution history, even that section isn’t recommended.

It would be a mistake to think Li lacks insight solely because of the censorious regime. All this information is freely available to the millions of Chinese who work, travel and study overseas. Within the great Chinese firewall, you can use proxy servers and apparently even get (illegal) phone alerts as to the latest censorship dictates. So the apathy and disinterest concerning this specific issue is more deep seated – China’s present day problems loom very large and are all consuming.

Worth remembering too maybe that most Americans have no idea that Columbus was a genocidal monster who murdered babies, raped children, and tortured large numbers of people to death. Selective memory is hardly the sole provenance of China. Which isn’t to excuse it, but still always worth remembering that the other person’s mote tends to be easier to see.

Noah, I would be the first to admit that the plank in our own eye (meaning the US in this case) needs to be addressed. It is a similar problem: we don’t talk about the wholesale destruction of native lifeways, how the first Indian boarding schools developed directly out of prison camps, the Shays and Whiskey rebellions, American imperialism from the late 19th century on, etc. I had to learn this all well after that classes I took in high school labeled “American History” that more often than not tried to make Southern “states’ rights” seem like something virtuous.

I can only speak from my own limited experience in China, along with that of my colleagues and students. Those my age and older, who, admittedly, are mostly left leaning and academics, are all too aware of the pressures on what you can and cannot talk about. My students, who are much younger, both Chinese and non alike, appear to be more or less oblivious to what they don’t know. So, while the information is there, they demonstrate little desire to know it. In that, I think you’re right, there is something much more deeply seeded than just reacting to official pressure.

Oh, and despite my qualms, I did like the piece.

Suat, It may be obvious from my previous comments that we see some aspects of American policy differently, including some you allude to in this review. Nevertheless, this was an excellent, thoughtful, exceptionally well-informed piece. I am especially impressed at your ability to critically, but fairly, examine so many perspectives on the issues brought up in A Chinese Life — especially your own.

For a thorough discussion of the interplay between the economic and political power of the masses and how they affect development, I recommend Acemoglu and Robinson’s Why Nations Fail. I should admit that it has a prescriptive ax to grind, but it may be a good one. I’m assuming you haven’t read it already.

Thanks for the book recommendation – I’ll read it, probably through gritted teeth but that’s not unusual. The preface seems a bit Fukuyama-ish in its faith in the West and way too naive about the Arab Spring, but that’s all I’ve read. And I do believe that Thomas Piketty and others might disagree that “countries such as Great Britain and the United States became rich because their citizens overthrew the elites who controlled power.” I think some Indians would have something to say concerning the former case at least.

Presumably black folks could offer some counter-evidence to the idea that the U.S. became rich through egalitarian practice as well.

Li Kunwu’s own comics (which I used to read in elementary school) have always been small life anecdotes that have some visual wit, but not much else. The last time I saw his comic was one about driving cars from ten years ago. Judging from that one, his work had become even more banal. “A Chinese Life” at least allowed him to show off more of his artwork. Otherwise the book is exactly what Ng Suat Tong said.

Suat, if memory serves, the authors economically compare pre-Colombian Indians to both each other and their European contemporaries. I don’t remember post-Colombian Indians coming up at all — possibly because the relationship was less economic exploitation, more economically driven, incidental genocide. By “incidental,” I mean it was more often a thoughtless side effect of other activities — the reckless disregard for life, instead of pre-meditated murder.

Noah, the authors had a lot to say regarding the economic effect of chattel slavery and even the lack of social mobility among whites in the South — almost all of it bad. The one exception was their admiration for the intellectual property rights of slaves, who could and did hold patents even while they themselves were considered property. Because this is America, and we’re not going to let a little thing like a carefully constructed supremacist ideology that rationalizes dehumanizing violence and servitude hinder capitalist innovation! (Okay, that’s my interpretation of their data, but I think de Tocqueville would agree.)

Hmm, I’m pretty sure Noah will have something to say about the “thoughtless side effect” question with regards post-Colombian Indians. But I was actually talking about the Indians of Asia and their relationship to the British empire.

Anyway, once again thanks for the recommendation. I’ve since read Acemoglu et al’s paper on “The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development” which is the bedrock for the book apparently. The paper does strike me as strangely simplistic and even seems composed from a fixed ideological stance. In any case, as is common with such works, the discussion resulting from the book/paper is sometimes as (if not more) interesting; especially the reply by Jeffrey Sachs which is pretty impressive:

http://jeffsachs.org/2012/12/reply-to-acemoglu-and-robinsons-response-to-my-book-review/

Also this one isn’t bad:

http://levine.sscnet.ucla.edu/general/aandrreview.pdf

Okay, I just re-read this and realized Suat was talking about Indians in India, not mis-named First Americans. I don’t remember if the authors address exploitation of the Jewel of the Empire or not, but they cover many examples of colonialism and its systematically punishing effects on the economy as a whole in order to benefit the elite few. Brits in South Africa got special attention.

Yeah; Columbus wasn’t accidentally committing genocide. He ordered young children raped, set dogs on people, chopped off folks’ hands; rampant deliberate slaughter. Aided and abetted by disease, obviously, but I think comparing him to Stalin or Hitler or Mao is pretty reasonable; main difference is he didn’t have the massive state apparatus and modern weaponry at his command. The will to genocide was sure there though (and he killed a ton of people.)

Noah, I was talking about the general thrust of history, not Columbus in particular, because I am woefully uninformed about the details of his exploration. You have successfully convinced me to wait to learn more until a day when my stomach and my attitude about humanity can take the attack.

Really long response to Suat follows. Sorry.

Suat, thanks very much for pointing out these reviews. My response is late because I waited for an opportunity to sit down and absorb them. They were great — informative and thought-provoking, making a real contribution to the discussion beyond simply passing judgment on Why Nations Fail.

Both reviews point out valid contributions of the book, and both point out legitimate flaws in the data and the argumentation. They describe Why Nations Fail as asserting the primacy of inclusive political institutions over all else. My own reading was that inclusive economic institutions are primary, and inclusive political institutions are necessary to create and preserve them.

Sachs’ review is best understood after reading both his more critical original review and Acemoglu and Robinson’s snarky reply. Sachs includes links to both in the article you linked. Sachs makes a great case for the importance of technological diffusion and disease, among many other points. But his argument has flaws. For example, he uses the formerly authoritative institutions in the Asian Tigers to disprove A & R’s thesis, but he ignores two of their key points that explain the Tigers’ success. The first is that effective central government is a pre-requisite, and the second is that extractive institutions can succeed until their unwillingness to allow creative destruction halts progress. Then the economies either become inclusive or stagnate. The Tigers did this. He also acknowledges that A & R predict China will follow the same path in his original review, then seems to forget that point later.

The flaws in Boldrin, Levine, and Modica’s review are a little more significant. Boldrin, Levine, and Modica argue that post-colonial Zimbabwe’s institutions are more inclusive than Rhodesia’s. They attempt to use this as a counter-example to Acemoglu and Robinson’s case. I don’t think Zimbabwe’s institutions under Mugabe have been more inclusive at all. They’re a better example of A & R’s point that colonial institutions are often replaced by locally-led institutions that are similarly exploitative (except moreso). B, L, and M also try to argue “that Russia did well under extractive communist institutions,” merely because the Party was able to turn what little economic output they had toward military technology. This is a particularly bizarre assertion, considering that the Soviet Union was essentially a well-armed third world state despite its educated populace and tremendous wealth in natural resources. They further highlight their blind spot in the following passage: “The fact is that Germany has done well under all sorts of institutions – as much so under the non-benevolent dictatorship of Hitler as the benevolent dictatorship of Bismark. And it has done well as a post second world war democracy. All of which leads one to wonder: maybe it isn’t the institutions that matter? Maybe it is being German that counts?” Of course, East Germany didn’t do well at all under Communism despite their great cultural advantages, leading P.J. O’Rourke to conclude that Communism was so bad that it made a nation of Germans poor.

Nevertheless, Boldrin, Levine, and Modica still write the more enjoyable review overall. They do a great summary of A&R’s main points in the first few paragraphs, and they do a better job than Sachs of pointing out the parts that matter. For example, they emphasize the contemporary relevance of A & R’s warning — that vested interests often hijack inclusive institutions, making them extractive for their own benefit and at great cost to society as a whole. Their analysis of “What It All Means,” which comprises the last 25% of the review, is outstanding, even though I don’t agree with every aspect of it. They do a terrific job of explaining what A & R’s thesis might mean to our own global economic situation. They also bring up key points that A & R leave unexplored, like competition between nations and the effects of debt and transnational institutions. Regarding competition between nations, I think A & R would argue that the trick was not necessarily being inclusive on an empirical scale, but more inclusive than one’s rivals. Bernard Lewis has made a similar point about the Caliphate – that it succeeded only as long as it was the most economically and politically liberal model.

Boldrin, Levine, and Modica end their review by saying that despite its flaws, everyone should read Why Nations Fail. I would add that everyone should start by reading their review.

There are other genocidal attacks on Native peoples other than Columbus’; Andrew Jackson’s actions, for example, or efforts to eliminate the culture through taking Native children from their parents. I think bracketing the depopulation of the Americas as incidental is inaccurate and misleading. I”m not an expert in all the history, but I’d say it’s more like long-term casual acceptance of genocide as a goal, with not-infrequent efforts to put that into action on a large and small scale, abetted and really made ultimately possible by the (from the European perspective) serendipitous effect of European diseases.

I don’t know the history well enough to effectively argue which side of the scale is greater, either. I just have the impression that steady westward expansion, which deprived First Americans of resources (and exposed them to disease), had a greater effect over time than those genocidal incidents — in the same way that steady water flow over time erodes more than the occasional flood.

Well…but the steady expansion involved systematic theft of Native American land, as well as attacks on Native American peoples. Westward expansion wasn’t a natural occurrence; it was a US policy, which was predicated on the assumption that Native people had no rights, weren’t actually human, and deserved to be abolished.

Related to this is BLM’s summary of Jared Diamond’s now famous idea that “competition between countries has been a potent force in driving innovation and subsequently growth.” One side effect of their short summary is that it brings to the fore the idea that one should not discount humanity’s deep desire to subjugate and kill each other as one of the factors in technological progress and hence growth. This rather than A&R’s rather limited/saccharine view of human progress.

Noah, I agree and disagree. The conquest of what is now the continental United States took three hundred years. There was no one consistent, “systematic” policy about anything over that length of time, and there was certainly no commonly held opinion on the intrinsic value of the land’s original occupants. During that time, the indigenous peoples of North America had some friends and advocates among the newcomers, as well as some interlocutors who dealt with them as fairly (or unfairly) as they did their fellow whites or fellow blacks. Even the Trail of Tears occurred over the clear objection of the U.S. Supreme Court, if I remember correctly. You can’t find supporters who are more “establishment” than that.

However, for many people, the assumptions you talk about were real. They used those assumptions to motivate or at least rationalize their actions. Others who knew better did nothing, as is always the case with socially acceptable evil. So whether the result of a vast conspiracy or callous, avaricious indifference to human life, the result is the same.

Suat, I fully concur.

Racism isn’t exactly a vast conspiracy. If you just assume some people are less human than others, most of the policy implications follow.