A little bit back I wrote a piece about the upcoming black Captain America and the idea of Black superheroes more generally. In the essay I said:

So, on the one hand, a black Captain America is a strong, and welcome, statement that the American dream isn’t just for white people — that black folks can, and for that matter, have been heroes. On the other hand, though, a black superhero who just does the superhero thing of fighting criminals or anti-American spies or traditional bad guys can seem like a capitulation. Fighting against crime in the U.S. means, way too often, putting black men behind bars. Will a black Captain America serve as a kind of “post-racial” justification for that law-and-order logic? Or will he, instead, open up a space to question whether law, order, and superheroics are always, and for everyone, a good?

Criminals in the United States are insistently conceived of as black. Superheroes are iconically crime fighters. A black superhero is forced to confront that contradiction one way or the other — since even ignoring it becomes a kind of confrontation.

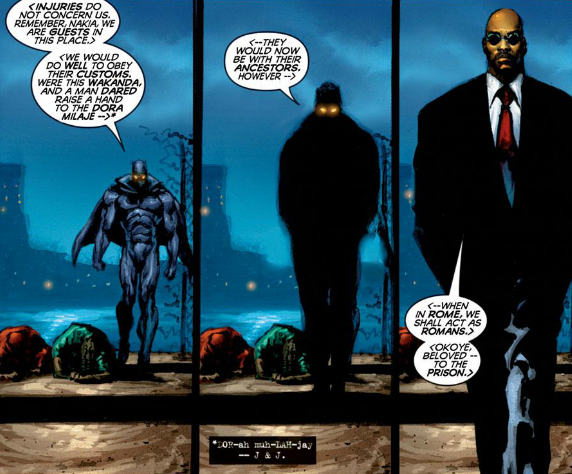

I just read the first volume of Christopher Priest’s Black Panther(art by Mark Texeira and Vince Evans), which is definitely aware of this issue, and works to address it. In the series, Black Panther is a superhero who isn’t really a superhero; he’s the king of Wakanda, a fantastically advanced African nation. He may pose as a crimefighter for his own reasons, but really he has only an at best peripheral interest in putting bad guys behind bars, or in fighting for truth, justice and the American way. You could say he’s passing as a superhero. He’s pretending to assimilate and to be one of those oh-so-folksy Kents, but in fact he’s still true to his advanced, alien Krypton — still an other, who does not belong in America, and who doesn’t have any particular desire to belong.

This is a clever, and powerful, critique of the superhero assimilation narrative, not least because of the metaphorical resonance. Black people, after all, are the one immigrant group that is never allowed to assimilate, and the one group that has most reason to know why assimilation with the as-it-turns-out-not-all-that -virtuous-Kents is not necessarily all that it’s cracked up to be.

At the same time, though, the comic is, at least in early issues, never quite willing to push the criticism all the way to its logical conclusion. Priest talks openly in his intro about the fact that the series is trying for compromise. This is most obvious in the narration by Everett K. Ross, a white guy who Priest says “interprets the Marvel Universe through his Everyman’s Eyes,” and who is “a new voice, seemingly hostile towards the Marevel Universe (and by extension, its fans.” That’s one way to read it…but you could also see Ross as a sop to those same fans, giving them an identifiable white point of insertion to interpret Panther’s amazing, mysterious blackness.

Priest’s negotiation with the superhero genre goes well beyond the use of Ross, though. The whole plot of the volume is designed to make Panther act like a regular old superhero, complete with tracking down criminals, interrogating suspects, and beating up (mostly black) gangsters. Wakanda finances a charity for inner city kids in New York City; the publicity poster child is mysteriously killed, and so Panther decides personally to abandon a volatile political situation in Wakanda in order to track down the girl’s murderer. He intends to return to Wakanda as soon as possible…but in his absence, there is a coup, and to avoid further bloodshed he is forced to remain in the U.S. and keep on superheroing. Tough break for the Panther, good luck for the superhero audience.

There is some ambivalence about Panther’s superheroing in the comic. His foster mother and others back in Wakanda tell him he’s being foolish for abandoning his kingship to be a cop (though his mom doesn’t put it quite that way.) And later it turns out his mother and the guy who usurps the throne were actually in cahoots to trick Panther to come to the New York. Rather than fighting the bad guys as a superhero, the bad guys essentially trick him into being a superhero. Supeheroing is a trap; to the extent that Black Panther is a superhero, he’s a rube.

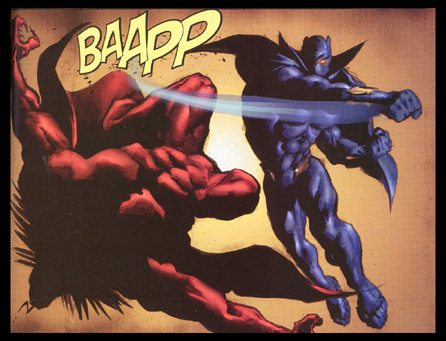

Just because the comic knows that superheroing is a trap, though, doesn’t change the fact that superheroing is a trap. Black Panther is presented as an awesomely powerful, superintelligent, spiritually advanced African king who knocks out the devil with one punch but still can’t get out of a story where his main function is to hit monsters.

“Why the hell are you wasting your time with this crap, you idiot?” is a barely subdued subconscious chorus that echoes jarringly against the more overt insistence that “Black Panther is awesome!” Making a black man a superhero, Priest suggests, can’t help but show the limits of superheroing; there’s a slapstick futility to gods and kings with vast powers slugging “bad guys,” rather than attending to the more consequential kingdoms and injustices that start to be hard to miss when the world isn’t quite so insularly white. You wonder, perhaps, if Priest is prodding, or questioning, his own genre investments — if he too, like his main character, feels a little hemmed in by the narrative in which he’s found himself; a story he clearly loves, but which just as clearly wasn’t made with him, or his (helplessly super) hero in mind.

After reading this piece and the one from Esquire, I really feel like you (or someone) need to discuss/look closely at Dwayne McDuffie’s Icon. To me, that comic deals more directly and more completely with the issues you’re talking about. It’s also just a fabulous comic deserving of more attention.

Well, I”m sure someone has looked at it! Not sure if I’ll get to it anytime soon…but maybe someday!

The thing I have on the shelf next is Static Shock…and Darryl Ayo commented on facebook that there are many black police, which is obviously true, and makes me wonder if I should revisit Chester Himes’ police series with some of these issues in mind…

Enjoyed this, Noah. I think it’s worth sticking with the series to see how Priest negotiates this (even if it’s inevitably unsatisfying). Priest later introduces a young black woman named Queen Divine Justice as a major part of the ensemble to articulate some of these critiques explicitly and on a way Ross couldn’t. The final issues of the series involve the Panther recruiting a NYC cop to be the/a new Panther, so that might be interesting in this context.

Sure they are many black police, and I am sure that many, (most? all?) deal with the contradictions inherent to their job that emerge from our racist society and the criminalizing of black bodies.

But as I said in that piece I wrote about “Invisible (Watch)men” that I have linked to many times – to me the issue that makes superheroes interesting in the perspective of race is the anonymity that usually goes along with that tradition – that is, white dudes in masks (of various kinds) taking the law into their own hands. They are not legally sanctioned, but implicitly exist to handle what they think the law can’t or won’t, when ironically what the law will frequently not or won’t handle is the myriad way people of color are disenfranchised.

I want a superhero (and I’d love to write this) who does not care about bank robbers or muggings, but works to fight against systematic racism – who exists in the superhero world as if the bad guys have already won.

Noah, I’d encourage you to read more–specifically with the plot regarding his mom and the usurper to his throne.

Priest wrote Panther as a man who was always three steps ahead of everybody else and used the fact that he was underestimated and misunderstood to his advantage on a constant basis. But he later turned the Panther’s super-competence against him in a sort of tragic way. Along the way in the series, there’s a complex story that hinges on an understanding of global economics and the aforementioned Queen Divine Justice, who comments on matters related to race.

Priest also addresses race pretty bluntly in his run on Steel.

I may well read more…the problem is it’s kind of not that great, so my enthusiasm for reading all the way through is somewhat limited. Maybe it gets better though.

Noah, Static Shock was great, but I can’t say enough about Icon. Of course some people have looked closely at it, notably Jeffrey A Brown’s book on Milestone Comics. But there really isn’t much scholarship on it, which is a shame because the book is partly about what Osvaldo asks for: a superhero who fights systemic racism. Icon begins with solving a hostage situation using somewhat typical superheroics, but it very quickly becomes something else. And the dynamic between the wealthy conservative Republican Icon and his poor, inner-city sidekick Rocket is very interesting.

Priest’s run is very uneven, I wouldn’t say it gets better so much as it has some interesting highlights. There’s a real sense that there’s a struggle of how to get 49+ issues out of this African king character, who’s constantly made to have reasons for running around america, or is constantly fighting off coups in his homeland.

I think one of the highlights was when Priest just did a wacky time travel story with Panther in the wild west without worrying about all of the “serious” plotlines.

Brannon wrote “The final issues of the series involve the Panther recruiting a NYC cop to be the/a new Panther, so that might be interesting in this context.”

That’s sort of accurate but not really how I’d describe the final issues. The later plotline involves a New York city cop named Kasper Cole finding Black Panther’s old costume and deciding to use it to fight the crimes he can’t fight as a law abiding cop.

His story involves being emasculated in a lot of ways and not fitting in. Kasper is also half black, half white/ Jewish, his name sort of implies this.

(Kasper calls back to Casper the ghost, a pale white character, Cole likely has an etymology with charcoal so suggests he’s both white and black. )

Kasper never had permission to be the Black Panther, but Panther ultimately puts him through an initiation and finds him worthy of being a sort of associated superhero named “white tiger”- and there seems to be a theme of reconnecting with africa or african culture being a source of empowerment, since he’s empowered by his association with Panther.

I think the first volume of Icon is really, really good. After that it feels like the concept is sort of played out, and if I recall correctly within a few issues they are resorting to a really silly Superman crossover and some space based plotlines.

” Black Panther is presented as an awesomely powerful, superintelligent, spiritually advanced African king who knocks out the devil with one punch but still can’t get out of a story where his main function is to hit monsters”

This is a really funny take, by the way. Panther’s not really three steps ahead of anyone at all, is he? No matter how many times the narrative insists he is…

The Kasper story continues in Priest’s “The Crew,” as does the emasculated hero riff. It’s there that the gender stuff made the whole thing pretty much unreadable, at least for me.

There are some problems with women in the first one; the assistants/bodyguards in the ridiculous outfits who won’t speak to anyone but him and are waiting for him to choose one of them to marry because of ancient tribal customs — that’s not so great…

“It’s there that the gender stuff made the whole thing pretty much unreadable, at least for me. ”

The Crew is definitely defined by male bonding because the women in the men’s lives are a pain in the ass- that’s a place I’m willing to go if an author has a compelling voice, and I don’t consume a lot of media like it.