This is from a ways back, when Caro would theorize at length in comments threads.

Caroling Small: Questions about storytelling and representation and all those things are literary themes. But literary narrative is also a lot about the manipulation of device. Device is higher level than prosecraft, and lower level than theme. Maus fails at the level of the sophistication of its devices. It relies too heavily on symbolism, and straight symbolism in literature is less sophisticated than the more elaborate deployment of metaphor or metonymy. This is why so many literary people sneer at it getting the Pulitzer: it’s a good instance of “medium-specificity constituting a free pass.”

Symbolism is a component of metaphor on some level, but literary metaphor is bidirectional whereas symbols are unidirectional. The technical definition of a symbol is something like “using a concrete object to represent an abstract idea,” although the “concrete object” can be a “figure of speech.” (Notice the visual reference there to “figure” — in pure prose, a symbol is metaphorically concrete, but it still has to be concrete to qualify as a symbol.) But in literary metaphor the concrete drops away; instead you are juxtaposing two — preferably more — relatively ungrounded and fluid abstractions and having them structure each other.

(It’s also important to guard against the metaphor itself then functioning as a symbol; it needs to be integrated back into the narrative in some way, so that the metaphor illuminates character or theme or casts the plot in a different light, etc.)

This all happens very self-consciously in postmodern fiction, which calls attention to these things happening and generally integrates a self-consciousness about device into the theme, so that device in some way is always referenced by the theme. However, with the exception of the self-conscious self-referentiality, it happens in non-pomo fiction too — in Shakespeare, in Shaw, in Austen, in every literary writer. To get to something that uses symbols as directly as Maus you have to go back to the great Renaissance allegories — and they are so much more elaborate in the sheer quantity of symbols. There’s no puzzle to Maus — and Watchmen isn’t nearly as puzzling as The Fairie Queen.

So the more you’re able to connect a myriad of abstractions to each other and to the devices used to build the narrative, the more literary the work is. If there aren’t multiple abstractions interacting independently of whatever is happening concretely (so abstractions that are not symbols) and working in the service of the theme, the work is not literary.

Ware’s pretty explicit about his imagocentrism and his concern with the materiality of the page. But images are definitionally concrete. What happens when you’re imagocentric and concerned with the materiality of the page is you elide this layer of device and have a closer interweave between the concrete materiality and the highest abstractions of theme. This is a medium-specific property of comics — indeed of visual art — that makes it more difficult to build “literary” — or logophilic — narratives.

Even visual abstraction is concrete in the sense I’m using the word here, because it is working at that epistemological limit where the distinction “abstract/concrete” that is so native to, even constitutive of, the logos breaks down and you are faced with the material, visual word, evacuated of meaning. This is why the Imaginary and Symbolic are so named: the shift from the image-world, where the abstract is concrete, to the symbolic where they’re separated so that the concrete can be made to represent the abstract — that is the emergence of the logos (or in poststructural-ese, the founding gesture of differance).

Ware and Gilbert and to a lesser extent Clowes are all overtly concerned with the visual aspects of representation — it’s extremely hard to be a cartoonist and not be. This does not make them bad; this is not a criticism. It doesn’t even entirely exclude them from being thought of as a graphic mode of “literature”. But it does make them significantly less logophilic. Eddie Campbell might honestly be the only person working in a narrative mode in English who doesn’t fall victim to this — and an awful lot of people will derogate him by saying his work is either “mere illustration” or too verbose/literary. But he really seems to understand what’s missing, what’s different.

And, you know, honestly, on a much, much less sophisticated and theoretical plane, the actual prose that there is in American comics generally just blows. It’s ugly and colloquial and the writers apparently have the vocabulary of an average high-schooler. Regardless of how much prose you include in a comic, every single word of the prose you include should be _amazing_ — or you should pay someone to write it for you. If you love words, you put in great words. Period.

Illustrated children’s books, including but not limited to comics that include children in their readership, tend to be BRILLIANT at that, actually. But it’s really easier in children’s books, because the ideas are simpler, because there are less moving pieces — you can work with one device at a time rather than having to make the prose engage multiple devices simultaneously as well as multiple themes.

Er, disagreeement here. Understatement.

“If you love words, you put in great words. Period.”

Doubtful logic. Banal words can be very effective in works that are not, as you say, logophilic. Pinter is banal for long stretches, by your standard here. So is much (very good) children’s picture book writing, which often deliberately courts banality or flatness in text so as to open a space for the interpretation of images. See Sendak’s celebrated “Where the Wild Things Are,” for example, or Pat Hutchins’ “Rosie’s Walk” (or see Perry Nodelman’s acute analysis of these and other books in his monograph “Words about Pictures”).

“…the actual prose that there is in American comics generally just blows.” If you insist on seeing it as “prose,” it probably won’t be possible to convince you otherwise!

Q: Is a teleplay “prose”? Is a play?

“Maus fails at the level of the sophistication of its devices. It relies too heavily on symbolism…”

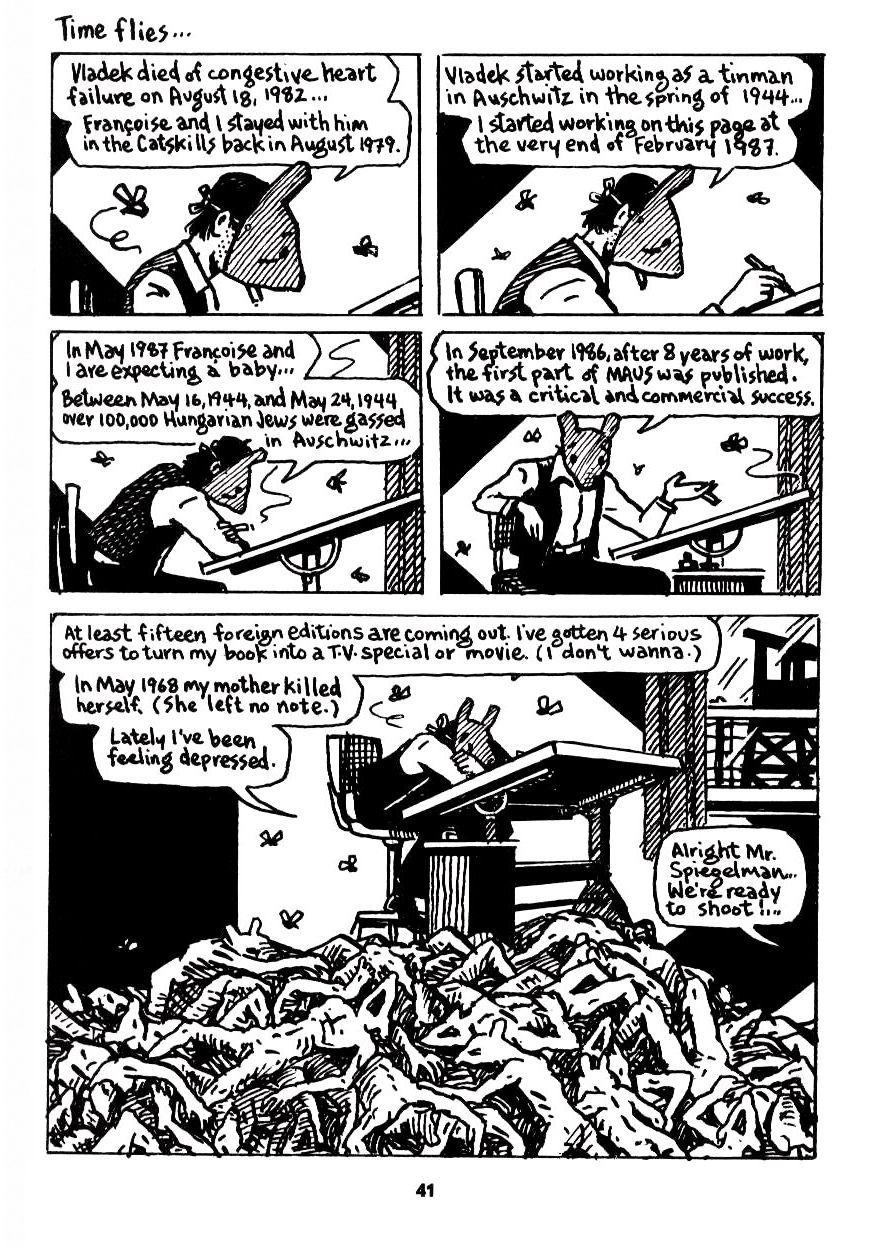

By now it is a truism of Maus criticism that its symbolism self-destructs, i.e. seeks to complicate and question itself to such a degree that it finally serves a purpose other than simple one-to-one correspondence. For that self-reflexive critique to work, and for the work to call identity into question as it does, the first-order symbolism of the animal metaphor HAS to be obvious. That does not constitute a failure.

“…it’s a good instance of ‘medium-specificity constituting a free pass.'”

Medium-specificity does not constitute a free pass. Medium-specificity startled and moved a great many readers who were frankly disinclined to give Spiegelman or any other comics creator a free pass. Medium-specificity is the condition and ground of Maus’s narrative, not some kind of handicap or hedge.

Smart, smart stuff above, but, wow, IMO way wrong.

Not sure Caro is reading, but…I really doubt she’s using the kind of simplistic definition of great prose you’re attributing to her. She’s looking for sophistication and thought, which of course can manifest as the artistic use of banality.

Using “Where the Wild Things Are” kind of nicely demonstrates the disconnect here. That’s a beautifully written book. “Simple” doesn’t mean “bad”; I’m sure Caro wouldn’t say it does. If literary comics were typically written as beautifully as Where The Wild Things Are, we’d be in a fairly different place.

With Maus, you’re saying that the symbolism has to be clumsy in order to deconstruct the clumsy symbolism. That seems like a low bar. Surely an artist of Spiegelman’s stature should be able to question tropes without making those tropes quite so self-evidently idiotic. Faulkner does it in “Light in August”; George Bernard Shaw does it in “Pygmalion,” Stanislaw Lem I think does it in “Solaris”. I just have trouble putting Maus next to any of those and seeing its use of symbolism as anything but a failure. The animal metaphor only has to be obvious to be deconstructed if you ignore huge swaths of literary examples.

There are comics artists who manage this with more sophistication. Lilli Carré, for example.

“Symbolism is a component of metaphor on some level, but literary metaphor is bidirectional whereas symbols are unidirectional… To get to something that uses symbols as directly as Maus you have to go back to the great Renaissance allegories — and they are so much more elaborate in the sheer quantity of symbols. There’s no puzzle to Maus — and Watchmen isn’t nearly as puzzling as The Fairie Queen.”

But Maus isn’t an allegory like the Fairie Queene, with figures representing abstract virtues and vices, or even a roman a clef. It’s not a story set on a farm where one day the cats decided to round up all the mice. It’s not even about cats and mice on the surface level (that’s the proto-Maus short story that ran in Funny Aminals, an approach Spiegelman discarded.) It’s explicitly about human beings in Nazi Germany and modern Rego Park. The animal motifs are a visual shorthand, and a highly stylized one at that. The cats vs. mice are a deliberate simplification standing for the brutal simplifications that assigned roles in the Holocaust. The device clarifies the action in a historical circumstance that saw vast numbers of people forced into relationships according to ethnicity and nationality, and simultaneously draws a veil over the lurid detail of those events in a manner analogous to prose.

(Also, I’ve seen some starry-eyed types try to explain Watchmen as an allegory, but… really? If Doctor Manhattan is the Bomb, is Silk Spectre the bikini?)

“{Maus] relies too heavily on symbolism, and straight symbolism in literature is less sophisticated than the more elaborate deployment of metaphor or metonymy. This is why so many literary people sneer at it getting the Pulitzer: it’s a good instance of “medium-specificity constituting a free pass.”

You are aware that Maus is not a work of fiction? I don’t mean to suggest that a memoir/biography can’t employ literary devices, but I wonder what extent and kind of metaphor and metonymy would have improved it.

And who are these literary people who sneer at Maus? Have they expressed their opinions in writing somewhere we can see?

“This all happens very self-consciously in postmodern fiction, which calls attention to these things happening and generally integrates a self-consciousness about device into the theme, so that device in some way is always referenced by the theme. However, with the exception of the self-conscious self-referentiality, it happens in non-pomo fiction too — in Shakespeare, in Shaw, in Austen, in every literary writer.”

This statement comes across in context as another description of literary qualities that Maus doesn’t have. But Maus does exactly that. You can’t miss it. I don’t even think it needs the chapter that makes the “masks” concept explicit, which really reads like Spiegelman defending himself against charges of taking the animal theme seriously, and renders it safe for classroom use. The artifice is apparent in the extreme simplification of the animal likenesses and the style in which every mark is printed at the same size of the original drawings.

“So the more you’re able to connect a myriad of abstractions to each other and to the devices used to build the narrative, the more literary the work is. If there aren’t multiple abstractions interacting independently of whatever is happening concretely (so abstractions that are not symbols) and working in the service of the theme, the work is not literary.”

OK, the extent to which this is the case with Maus really requires a thoughtful reading of Maus. Maybe this writer has carefully studied its and found it lacking, but I’m not seeing any analysis of its themes here.

“Ware’s pretty explicit about his imagocentrism and his concern with the materiality of the page. But images are definitionally concrete. What happens when you’re imagocentric and concerned with the materiality of the page is you elide this layer of device and have a closer interweave between the concrete materiality and the highest abstractions of theme. This is a medium-specific property of comics — indeed of visual art — that makes it more difficult to build “literary” — or logophilic — narratives.”

No, only if cartooning is defined as a practice of directly illustrating abstractions. There’s Ditko’s Eternity, and the old tradition of satirical drawing. But an illustrated world doesn’t necessarily bring the image any closer to the highest abstractions of theme than the physical environment described in a novel. Theme remains immaterial and invisible, even if it’s suggested by visual motifs.

Now, language is inherently more abstract and intellectual, and closer to immaterial concepts, but language is also available to comics and the visual element doesn’t have to interfere with that; consider the popular rule of thumb that the verbiage in a comic shouldn’t overlap with the information communicated by the visuals. And that’s a starting point for cartoonists, whatever flourishes they build from there.

Also, the use of “logophilic” as synonymous with “literary” after all this work has been done to define the literary as a complex deployment of abstractions is telling. Logophilia doesn’t point to a difference in sophistication between prose/poetry and comics, just that one side “likes words more”, or relies on them exclusively. And the solutions offered shortly after, in Campbell and the call for better prose in comics, just come down to more and better words.

“Ware and Gilbert and to a lesser extent Clowes are all overtly concerned with the visual aspects of representation — it’s extremely hard to be a cartoonist and not be. This does not make them bad; this is not a criticism. It doesn’t even entirely exclude them from being thought of as a graphic mode of “literature”. But it does make them significantly less logophilic.”

Um… I’m not sure where to start with this. It IS a criticism; the concern with visual aspects of representation is framed as a another barrier to making comics more “literary” and accessible to complexities of theme, metaphor, etc. But… being overtly concerned with visual aspects of representation in… a… visual/verbal medium… is like a poet thinking about language. For crying out loud. If a cartoonist thinks exclusively about the visual element and dashes off the language as an afterthought, then yes, that’s a problem. But thoughtfulness about visual representation in itself is just fundamental to serious comic-making.

I don’t understand on what basis Clowes is judged as less concerned with visual representation than Ware and Gilbert (Hernandez?) I’d say look at Ice Haven, The Death Ray and Wilson, but that suggests he wasn’t thinking about it before he started using bold stylistic changes in a single story.

“And, you know, honestly, on a much, much less sophisticated and theoretical plane, the actual prose that there is in American comics generally just blows. It’s ugly and colloquial and the writers apparently have the vocabulary of an average high-schooler.”

I’m sympathetic to the idea that the prose in American comics (and not from elsewhere? Are we including Marvel/DC, and good God why?) could be better, but none of these characterists are really a problem, except that the cartoonist’s vocabulary is not necessarily that of his or her characters’. A lot of comics restrict themselves to dialogue and first-person narration. 70s Marvel comics used some hefty vocabulary words and that didn’t help them.

“But it’s really easier in children’s books, because the ideas are simpler, because there are less moving pieces — you can work with one device at a time rather than having to make the prose engage multiple devices simultaneously as well as multiple themes.”

The only thing that’s necessarily simpler about children’s books is the language. A simultaneous multiplicity of devices and themes is possible, not to mention moral complexity and the potential for allegorical readings (not the same as straight-up allegory), other qualities I’d associate with literature. The kind of prose this writer is holding up as literary also doesn’t seem to allow for stylistic minimalism, a mode well suited to comics. Ah, but “literary” means more words, more…

There are two important tells here. One, Caro talks about postmodern self-consciousness as if Maus doesn’t have that. Two, holding up metaphor and metonymy as different and more sophisticated than the symbolism in Maus. Spiegelman’s animal masks are a visual metonymy, not the kind of allegory she means. Metaphor is not rigidly demarcated from other literary devices and it’s very reductive to confine Spiegelman’s animal theme to its one-for-one correspondences.

All this diagramming of literary symbolism is more a kind of freestanding English lecture than an examination of Maus. None of these opinions couldn’t have been gotten from hearsay that Maus uses mice for Jews and cats for Germans. If you get any closer it’s hard to justify putdowns like calling it a Renaissance allegory that would be better if it were more of a “puzzle,” as satisfying as that might feel when you’re blowing off steam on the internet.

I don’t know Chris; I’m quite familiar with Maus, and I think Caro’s points hold up well. You can disagree of course. But the reflexive “you don’t know the material well enough” strikes me as more knee-jerk fannishness than an actual effort to deal with the arguments Caro makes. If you think she’s wrong and are arguing that a closer reading of the material shows she’s wrong, then provide a reading that shows she’s wrong. This was a comment, not a rigorous essay originally, you know? Why not engage with it to demonstrate why you value Maus, rather than curling into a defensive crouch?

OK.

Caro talks about postmodern self-consciousness as if Maus doesn’t have that. Spiegelman’s animal masks are a visual metonymy, not the kind of allegory she means. Metaphor is not rigidly demarcated from other literary devices and it’s very reductive to confine Spiegelman’s animal theme to its one-for-one correspondences.

I don’t think Caro’s saying that Maus isn’t postmodern, or that it lacks self-consciousness. She’s saying it lacks sophistication compared to other literary works. And to me that seems about right.

And I don’t think it’s Caro who’s being reductive. I think she’s right that Spiegelman’s use of animal metaphors is fairly clumsy and obvious, not least when he’s shouting at you that the use of animal metaphors is clumsy and obvious.

I’m not sure I agree with Caro that this is a problem of comics formally; I think images can refer in metaphorical and subtle ways. I would say that it’s an issue of American comics historically not being very sophisticated.

I talk about Spiegelman’s clumsiness more here, fwiw.

There isn’t a thing in that essay about how Spiegelman’s animal metonymy is clumsy. When I said “animal masks” I wasn’t talking about the part where he explicitly draws them as masks, that’s a common description of the way he uses animal likenesses throughout the book. Very poor analysis of those pages, by the way.

“There isn’t a thing in that essay about how Spiegelman’s animal metonymy is clumsy.”

There’s a lot about how his use of metaphor (and for that matter page layout) is clumsy, it seems like to me.

Here’s another that is maybe more directed to this particular issue.

And you didn’t provide a reading that showed Caro was wrong, incidentally.

Yes, I did. What you haven’t done is answer any of my points, instead demanding that I write a new essay about Maus. I said that Maus is a visual metonymy that incorporates a self-consciousness about its devices into its theme, not an allegory that should be more of a puzzle. That places it in the “literary” category Caro sets up and makes hash of her argument. I also said its symbolism isn’t only unidirectional, that is, it doesn’t stop working past the point you “solve the puzzle” that mice are Jews and cats are Germans. It takes up dehumanizing Nazi rhetoric of Jews as vermin, the mass killings using pesticides, and their attempts at a “final solution” with its generational storyline, i.e. here are generations of “vermin” who survived and had to make sense of their parents and themselves, etc. Those are multiple abstractions the device is communicating with while floating lightly on the narrative itself in the sense that we know these are not even literal mice from the language and from the human likenesses in Prisoner on the Hell Planet and Vladek’s photograph. The comparison to prosecraft is apt, not exactly like it but complicating Caro’s image vs. logos theorizing. Your own writings on Maus just strike me as aesthetically crude and have a personal edge in the vein of Pekar and Rall’s attacks, this sense of grievance at Spiegelman himself that seems to keep coming up. I’ll respond to those posts more if I have time, but unless you have some Russian nesting doll of an essay that you wrote before them that brilliantly explains why the animal devices fail you’re not convincing me of that or answering my points. And you did choose to make this comment into a post.

I have no grievance with Spiegelman. I don’t know him; never met him; from all I hear he’s a very pleasant individual in person. The only grievance I have with him is that many of his comics suck.

And, you know, you’re own posts are pretty cranky and verge on personal attacks. Does that mean you hate me and therefore all your arguments are moot? No, I assume it just means that you don’t like my writing (or Caro’s.) Maybe I’m being overly generous and you have some secret reason to despise me personally, but I really doubt it.

You don’t have to write an essay. But I still don’t think you’re really engaging with or answering Caro’s point, which, as I understand it, is not that Maus is a pure allegory, but that the symbolism of mice as Jews is heavy-handed, and doesn’t include ambiguity or mystery. You say that the symbolism “floats lightly on the narrative”, but none of your examples suggest it floats lightly. Demonstrating that the mice aren’t really mice by having a sequence where folks are human; that seems pretty blunt, don’t you think? Quite a bit different than, say, Kafka, where Samsa is and isn’t a bug, without that ever being resolved definitively — or even something like Watership Down, where again the status of the animals, and their relationship to humans, is amorphous and ambiguous. Spiegelman’s metaphor starts out in an allegorical vein, and then is somewhat complicated…but the complications are all again quite rote, it seems to me.

In one of those posts I linked I argued that in many cases Spiegelman undercuts the image you see by referring to language as the real (that is, someone will say the equivalent of, we’re not really mice.) That seems like it’s subtle or questioning representation, but to me it just seems to reify language at the expense of image. Which again, is pretty blunt and rudimentary by the standards of great literature (like Kafka.)

There are comics that do complicated things with symbolism and image. Tsuge, Moto Hagio, Lilli Carre, even Alan Moore and his collaborators. That’s why I don’t agree with Caro that it’s a problem with the comics form per se. But I think it is a problem with Maus.

I’m not made of time today so I may answer more of this later, but… do you know what a metonymy is? That’s the practice of referring to one thing as another when there’s no literal claim that the one thing is the other. Not the same as the Metamorphosis, where Samsa is and isn’t a bug but also deals with a lot of literal, physical business related to having a bug’s body. An example of a metonymy is referring to a character as a “suit” when there is no claim being made that this is an ambulatory, hollow, talking suit, and yet the term communicates something about his presence in the story, a sense in which the other characters are confronted by a presentation and a uniform and the real person is somewhere else. That sense in which there is no question of a literal walking suit is what you’re calling blunt and rudimentary. Caro correctly describes metonymy and metaphor as being more sophisticated than unidirectional allegory. And Maus is at least one level of ambiguity past my example because that writer is still trying to convince us that “suit” says something important about the character, and not following him home to his wife and kids and then to visit his dad and learn about the old country while still wearing that term “suit”.

Sure, I know what metonymy is. And sure, I think referring to someone as a “suit” is about the level of complexity you’ve got in Maus.

Metamophosis is quite different. There is no “literal” business with the bug’s body. There is no bug; there is no body. There’s no real; it’s a story. The transformation into a bug is in part about that fact that there is no body; the more literal it becomes with the giant bug, the more it’s *not literal*.

If you see a similar sophistication in Maus’ “hey kids, he’s a mouse, but not *really* a mouse, because damn the Holocaust really happened” — well, different strokes and all that. I remain unconvinced.