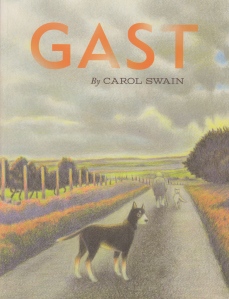

Carol Swain’s new graphic novel Gast (Fantagraphics, 2014)

After finishing Carol Swain’s Gast a few days ago, I found myself returning to Thierry Groensteen’s discussion of densité from Chapter 3 of Bande dessinée et narration (see pages 44 and 45 of the original French edition and page 44 of Comics and Narration, Ann Miller’s English translation). Gast, like Elisha Lim’s 100 Crushes (which I hope to write about soon), is a comic I’ve been enthusiastically recommending to friends. Swain tells the story of a young girl name Helen who, with the help of two dogs, a sheep, and a few birds, searches for clues about her neighbor Emrys and his sudden death.

I want to say very little about Helen and the small Welsh village where she and her family live. The mystery of Emrys’s life and death should reveal itself to the reader in the same slow, deliberate fashion that Helen comes to understand it. I’ll focus my attention instead on some of Swain’s page designs so as not to give away too much of the story. In Gast, the “density” of Swain’s compositions suggest the distance between Helen and Emyrs, a character who haunts the narrative. Like the protagonist of Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan or Art Spiegelman’s Maus, Helen has the impossible task of piecing together the fragments left behind by a man reluctant to tell his story. Swain conveys Helen’s joy and confusion in a series of regular, nine-panel grids. These repetitions convey the density, I think, of Helen’s curiosity and of Emrys’s loneliness. At times, in fact, it is not clear where one begins and the other ends—an important point to consider, especially for the reader, who, like Helen, is left to decide why Emrys took his own life.

In order to apply Groensteen’s idea of densité to Gast I am thinking phenomenologically. Doing so opens up a number of theoretical possibilities, especially if the densité Groensteen describes can be read as synonymous, for example, with the density philosopher George Yancy examines in his recent book Look, a White! First, let me quote from Ann Miller’s English translation of Bande dessinée et narration before I consider density in relation to Yancy’s discussion of race: “A further consideration for the critical appreciation of page layout needs to be introduced,” Groensteen explains.

This is density, alluded to above. By this I mean the variability in the number of panels that make up the page. It is obvious that a page composed of five panels will appear less dense (as potential reading matter) than a page that has three times as many. (Groensteen 44)

What role does density serve, then, for both the artist and for the reader? Later in the chapter, Groensteen argues that, in Chris Ware’s comics, these dense and complex page designs have an expressive purpose: “Symmetry, in particular,” Groensteen argues, “is used by Ware to heighten the legibility of the binary oppositions that structure the spatio-temporal development of the story, such as interior/exterior, past/present, or day/night. But when two large images mirror each other on facing pages,” Groensteen adds, “this can also signify other oppositions or correspondences” (49-50). The “binary oppositions” Groensteen discusses here are also present in Gast: male/female, old/young, urban/rural, animal/human. The use of words and pictures to convey meaning in comics also implies the phenomenological density of consciousness itself: the sudden awareness of the self in relation to the other.

In Chapter 1 of Look, a White!, Yancy argues that what he describes as “the lived density of race” (17) demands new forms of expression. Although he is writing here about philosophy, I am interested in how we might apply his ideas to the comics we create, read, and study:

To communicate an experience that is difficult to express, the very medium itself may need to change. On this score, perhaps philosophers need to write poetry or make films. When it comes to a deeper, thicker philosophical engagement with issues of race, the medium has to change to something dynamically expressive, something that forces the reader/listener to feel what is being communicated, to empathize with greater ability, to imagine with greater fullness and power. (Yancy 30)

Notice that in his second sentence Yancy refers to poetry and film, two forms with close ties to comics (see, for example, Hillary Chute’s recent essay from Poetry Magazine). How might a page filled with words and pictures, for example, enable “the reader/listener to feel” with greater intensity? For Yancy, of course, this affective experience must accompany or inspire real change. Feeling something is one thing. Acting on a feeling of identification requires radical selflessness and love.

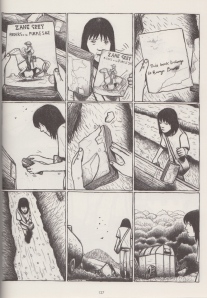

Page 127 of Gast

For Helen, the gradual shift from theory—her curiosity about Emrys’s life and death—to praxis takes shape on page 127, where she finds one of her neighbor’s books. In the first panel, we see a copy of Zane Grey’s Riders of the Purple Sage. The book is fragile. In the second panel, she tears the illustrated cover from its binding. “This book belongs to Emrys Bowen,” reads a note written on the back of the cover. In the fourth panel, she tucks that slip of paper beneath her arm, and holds the book in her hand in panel #5. She runs her fingers across the pages. Bits of paper fall like leaves.

Like Gatsby’s worn edition of Hopalong Cassidy in the final pages of Fitzgerald’s novel, Emrys’s copy of Riders of the Purple Sage reveals, perhaps, the dream image he cherished of himself. But, then again, no—as Helen tosses the book aside in the next panel, she implies that Emrys refused to play the role of the rugged cowboy. She conceals the torn cover in her bag.

Swain implies that, as readers, we would be wise to be suspicious of allusions. This sudden reference to another text cannot convey the full complexity of Emrys’s consciousness. As I read Gast, I thought of another writer who spent his career recording the silences of rural spaces. Most of the late John McGahern’s novels are set in Country Leitrim in northwest Ireland, not far from Yeats’s home of Sligo. In the introduction to his 1974 novel The Leavetaking, McGahern, who revised the novel in 1984, discusses the challenges of writing both self and other. “The Leavetaking was written as a love story,” McGahern explains,

its two parts deliberately different in style. It was an attempt to reflect the purity of feeling with which all the remembered “I” comes to us, the banal and the precious alike; and yet how that more than “I”—the beloved, the “otherest,” the most trusted moments of that life—stumbles continually away from us as poor reportage, and to see if these disparates could in any way be made true to one another. (McGahern 5)

Like Yancy, McGahern suggests other terms we might use to describe the density of experience expressed on page 127 of Gast: where do the “I” and “the ‘otherest’” meet?

As I study the last three panels on page 127, I find myself wishing I could retrieve Emrys’s copy of Riders of the Purple Sage. What if we missed something? What if the book contains the key to understanding Emrys? But the grid prevents me from turning back. I must follow Helen as she walks to Emrys’s house, just as I must follow McGahern’s narrator as he moves from rural Ireland to Dublin to London and back again (as I try to disentangle the real from the imagined in McGahern’s autobiographical fiction, most of which takes place in the same region of Ireland where my paternal grandmother, Mary Anne Bohan, was born in 1910).

Both McGahern and Swain tell their stories with clarity and compassion. Swain’s use of the grid, I think, is a reminder of the inevitable barriers between the subject and the object being observed. These barriers, like the borders that separate one panel from the next, suggest that densité is both an aesthetic choice and a phenomenological imperative: the storyteller and the reader must take into account what McGahern calls “the banal and the precious alike” in order to make less terrifying the space between the “I” and “the ‘otherest.'”

Can we read Groensteen’s densité, then, as a synonym for the density that Yancy describes? Can you think of other page designs that seek to express the phenomenology of the self? Do comics provide a means of eliminating the distance between the two?

References

Groensteen, Thierry. Bande dessinée et narration: Système de la bande dessinée 2. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 2011. Print.

Groensteen, Thierry. Comics and Narration. Trans. Ann Miller. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 2013. Print.

McGahern, John. The Leavetaking. London: Faber and Faber, 1984. Print.

Swain, Carol. Gast. Seattle: Fantagraphics, 2014. Print.

Yancy, George. Look, a White! Philosophical Essays on Whiteness. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2012. Print.

This is a cross-post from my blog. Thanks to Qiana and Adrielle for inviting me! Thanks also to my dad’s cousin Oliver Gilhooley of Mohill, Co. Leitrim, for taking us to the John McGahern Library at Lough Rynn Castle in the summer of 2012. Oliver, a great storyteller himself, also gave us a suggested reading list of McGahern’s fiction.

The McGahern Library at Lough Rynn. Photo courtesy of Allison Felus.

Thanks for this post, Brian. The way you’ve used Groensteen as a point of departure for evaluating page density and its philosophical dimensions gives me a lot to consider here. I definitely think the page from “The Harvey Pekar Name Story” could benefit from this kind of reading.

So I’m wondering – in the page from Gast, is it also the materiality of the pictured book that helps to furnish the layout with the kind of philosophical thickness and depth that Yancy describes? I like the way the book provides another row of inset panels at odd and uneven angles with, as you say, bits of the edge falling away. The book frames inside the panels make them look crowded and incomplete. This physical placement would further support the notion that we should be “suspicious of allusions” particularly considering how after she tosses the book, the panels widen and draw back, allowing us (and Helen) more room to breathe and reflect.

I was also going to ask if the layout on this page is a departure from the rest of the book and what that might mean, but I’m going to order my own copy of Gast and find out for myself….!

This is a really great take on Gast.

I’ve been of fan of Carol Swain ever since Mauritania (in the early 90s?). The gorgeous artwork and the somewhat abstract story lines…

I read Gast a couple of weeks ago and thought it was a brilliant Carol Swain work, as usual. But I remember thinking after finishing it “geez, this isn’t going to get reviewed or written about at all”. If one were to employ the standard reviewing mode and recap the story line, it might seem somewhat simplistic (or gimmicky, even).

I’m pretty sure Mauretania wasn’t by Swain? A fine cartoonist, to be sure.

Mauretania was mostly Chris Reynolds’ thing, but Carol Swain did a substantial number of shorter stories in it.

She had her own series later — various versions of Way Out Strips.

Thanks, Qiana and Lars! I enjoyed writing about Gast. For the roundtable, I’d originally had an idea to write about Jack Kirby in honor of his birthday (maybe next time), but I decided to write about Gast so that I wouldn’t forget the experience of reading it for the first time. I’ll look forward to hearing what you think when you read it, too, Qiana.

Also, I like the idea of the cover of Grey’s novel serving as another panel-within-a-panel. This is a technique Swain uses quite a lot in the book as Helen takes notes on what she discovers about Emrys and we, as readers, see the pages of her journal. Like the Pekar story you wrote about, Qiana, Swain also includes a number of silent panels to punctuate Helen’s reflections. And, like Crumb, Swain varies her compositions very little. Most of the pages have the same 9-panel grid, with a few important exceptions.

To return to Pekar for a moment, for me Crumb’s panel arrangements in “The Harvey Pekar Name Story” suggest the infinite–that there might in fact be an endless series of speakers named Harvey Pekar, from moment to moment. Qiana, you know I’m teaching Middle Passage this semester (speaking of phenomenological texts), and as I read Pekar and Crumb I thought of Johnson’s opening epigram from the Upanishads: “Who sees variety and not the Unity wanders on from death to death.” Maybe this is another way to read these “dense” pages: as an attempt to see that “Unity” take shape–that is, the multiple panels suggest the multiplicity of sensory information that we take in, but the page itself is a means of organizing all of that data into a unified, compelling, and compassionate statement of oneness.

And, to Lars’s point, writing about Gast without revealing what happens was very difficult. I made some cuts as I was writing so as not to summarize and then reveal certain important shifts in the story. We begin to see Emrys from Helen’s perspective–that of an 11-year-old still trying to adjust to life in Wales. But, like Helen, we learn the details of Emrys’s life gradually, and then we’ve got to integrate all of those facts into a cohesive narrative. It’s quite an experience!

I’m looking forward to reading more of Swain’s work, including the stories Lars and Alex just mentioned. Meanwhile, I’ve started carrying around a copy of Gast and lending it to friends. I did the same with Gaylord Phoenix and John P.’s Perfect Example, so Gast is fast becoming one of my favorites. Gast and Lim’s 100 Crushes are probably my two favorite comics so far this year. Books like this remind me of why I fell in love with comics in the first place.