Last summer, I wrote a piece for the Atlantic in which I argued that Orange Is the New Black (OITNB)fails to effectively critique prison as an institution because prison as an institution in the United States is directed mostly at men, and OITNB presents prison as bad because it victimizes women. The piece went semi-viral as a hate read, and was widely denounced. Jezebel wrote an article with the very Jezebel title “Writer Doesn’t Understand Why Show About Women’s Prison Has So Few Men.” Music critic Brandon Soderberg called me as a “clueless cracker pedant” on Twitter. Folks I liked and respected told me in no uncertain terms that what I had written was unfeminist and generally awful. There was a massive comment thread with people lining up to tell me I was stupid and should shut up. The left, the damn left, in all its insular self-righteousness, would not tolerate brave dissent such as mine.

Or at least, that’s the conclusion I would come to if I were Jonathan Chait. Chait has written a long article for New York magazine in which he bemoaned the return of political correctness and the toxic culture of the left. Chait points to Hanna Rosin, who wrote a book about the current plight of men, and was ridiculed with a hashtag; he also singles out an invitation-only Facebook group where people argueloudly with each other. My experience could be another data point for him, yet one more example of how “swarms of jeering critics can materialize in an instant” terrifying the heterodox leftist or liberal into silence.

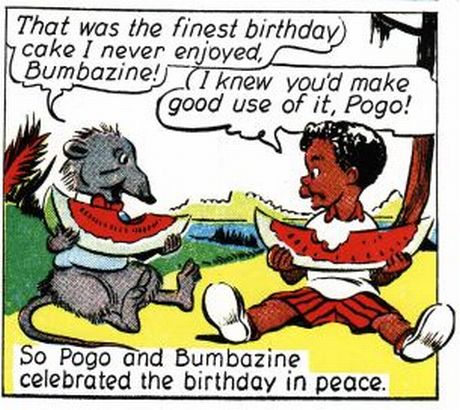

There’s a couple of problems with Chait’s thesis, though. First of all, there’s just nothing in his article or in his examples that makes a case that discourse on the broadly defined left is somehow nastier than discourse on the right, or in the center, or out in directionless space. The first controversial piece I wrote for the web was for The Comics Journal. I reviewed Art Spiegelman’s In the Shadow of No Towers and my piece was headlined “In the Shadow of No Talent.” TCJ readers lost their shit and at least one person wished for the death of me and my family. It was exactly the sort of intemperate lashing out at dissent that Chait denigrates — but it didn’t have anything to do with political correctness or a culture of Marxist intolerance. It had to do with comics fans not wanting to hear me tell them that the thing they liked wasn’t any good.

Since then I’ve been told that I am stupid and that I should shut up by lots of Men’s Rights Activists, some feminists, some romance fans, many comics readers, fans of Breaking Bad, fans of The Hobbit, some leftists, and many right-wingers. I’ve even been abused by a fair number of supposedly free-speech-loving liberals and libertarians, who, when it comes to online behavior, aren’t any more tolerant of dissent than anyone else as far as I can tell. In a recent discussion of Charlie Hebdo, one First Amendment lover told me that if I didn’t like America, I could leave it — because free speech means exiling folks who say things you don’t like. Maybe, as Gawker’s Alex Pareene says, the liberal Chait is especially thin-skinned when it comes to criticism from his left. But one thing’s for sure: In terms of yelling at each other online, there are no red states and no blue states. There are only states of intemperate ire, and lots of them.

Chait is right, I think, that social media has changed the way social pressures work when it comes to speech. It used to be that conversations in the public sphere were limited and controlled by institutions. What you could say was controlled by what magazines (like, say, The New Republic, where Chait used to work) would print. That’s still true to some degree. But it’s also true that social media has made it possible for people who didn’t have a platform to speak loudly, astutely, randomly, continuously, profanely, violently—and often right there, just under an author’s prose, in the comments section. The roar can be deafening, and sometimes frightening.

I use the word frightening advisedly. Chait in his piece does that odd thing free-speech advocates sometimes do, and downplays the importance, or dangerousness of talking and expressing opinions. ” Mere expression of opposing ideas, in the form of a poster, is presented as a threatening act,” Chait sneers, denigrating an academic who found a pro-life sign on a college campus offensive. But speech is threatening, often, and aggressive. You could argue that a professor physically grabbing a sign from a student is an escalation, and I’d agree with you. But it’s not an escalation from zero

Chait is telling people on the left that they’re totalitarians; I’m telling him that he’s a fool. The intent, in both cases, is to cause a reaction, to disturb, to mock, to change the world, in some small way. If speech were utterly inconsequential, if it had no power, there wouldn’t be any point in defending it. The argument for free speech, surely, has to be built on the notion that speech does in fact have power. It’s because speech is worth listening to that you defend it, not because it isn’t.

And the cacophony of the internet is, contra Chait, often worth listening to. It’s given a voice to many folks who didn’t have one before. Chait takes a swipe at the 1990s’ anti-sex work policies of Catherine McKinnon, but he doesn’t mention that the social media he sneers at has been a huge boon to sex workers themselves, who can finally create their own platforms after decades of being silenced by both the right and the left.

Similarly, black women and other women of color have a major presence online, and are able to talk back to folks like Chait (or like me) in a way that wasn’t possible even twenty years ago. Chait doesn’t always like what these people tell him — he seems particularly disturbed by Brittney Cooper’s argument that reason is not always a useful tool against racism. But that’s how free speech works; people will sometimes say things you don’t like.

There are downsides to all this roiling speech, too. Chait seems to think the most serious problem is that white men and white women are sometimes told that their whiteness disqualifies them from speaking. “Under p.c. culture, the same idea can be expressed identically by two people but received differently depending on the race and sex of the individuals doing the expressing,” Chait moans.

And sure, as a white person, I find it unpleasant when my brilliant, beautiful ideas are dismissed because I’m white or male. But that problem pales (as it were) next to receiving actual death threats, being doxxed, or having SWAT teams sicced on your house — none of which Chait mentions, because none of those things are regular occurrences on the left. But other communities haven’t been so lucky. Being white on the internet may be a hard, sad, road, but it’s nothing compared to being a feminist video game developer. For that matter, being white on the Internet is not generally anything compared to being black on the Internet. As Ferguson activist Deray Mckesson told me, “the death threats aren’t fun. They put my address out there, that’s not fun. I get called a nigger more than I’ve ever been called that in my entire life. I’ve blocked over 9,000 people, so I don’t personally see it as much anymore, but my friends do.”

The Internet makes it possible for more people to speak more effectively than ever before in history. That also means it allows more people to issue death threats, shout obscenities, and harass others than ever before. Free speech, and for that matter democracy, has always been a balancing act between the polis and the mob — between unleashing speech to empower people, and trying to figure out how to prevent the power of speech being used to oppress, to terrorize, and even (through that call to the SWAT team, for example) to kill.

The Internet, and social media, have exacerbated these tensions; they increase the potential of speech, for good and ill. Those are problems we have to wrestle with. Jonathan Chait isn’t up to the task, in part because his obsession with the left leads him to focus on ideologies rather than methods; on who he wants to shut up, rather than on figuring out which kinds of speech, whatever the content, should be allowed, which shouldn’t, and how to deal with the difference. Fortunately, the Internet is full of talking people who, civilly and less so, can tell him where he’s wrong, and that he should shut up.