In the wake of the tragedies that have occurred in Paris over the last few days a number of commentators, some traditionally left-leaning and some more obviously right-wing, have suggested that the cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo contributed to the climate of extremism that led to these attacks. The arguments often take the form of a double assertion: first, that the cartoons in question were flagrant or “unnecessary” violations of the Muslim prohibition against images of the Prophet; and second, that these violations were motivated by Islamophobia and racism. The conclusion, merely implicit in some commentaries and more explicit in others, is that because the cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo were also racist bullies they bear a degree of culpability for what happened; consequently, they also make poor martyrs for either the profession of satirical cartooning or the right to free speech.

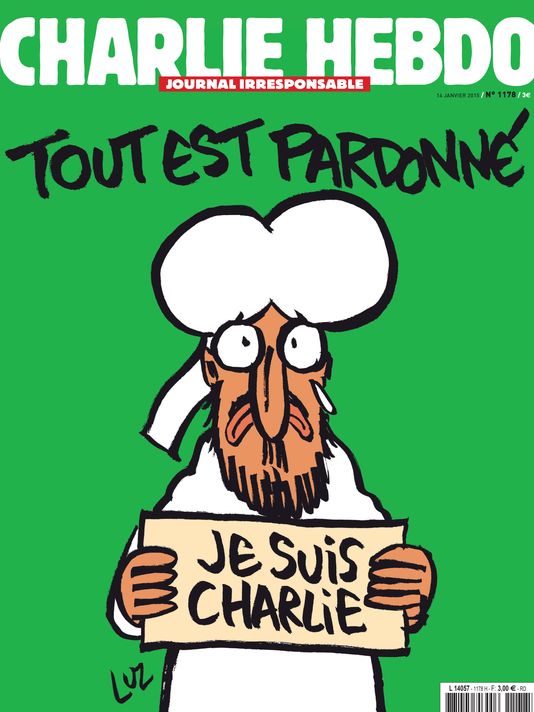

The cover of this week’s edition of Charlie Hebdo.

There are several problems with this argument, however. Most troublingly, to imply that the cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo contributed to the radicalization of Muslims by repeatedly violating an important tenet of Islam reduces the wide range of Muslim opinions on this specific issue to the extreme position held by the terrorists themselves. To take up this position is to fail to understand that the so-called “prohibition against images of the prophet” is actually already a radical interpretation of Islamic doctrine. No such prohibition exists in The Qu’ran. In fact, significant numbers of Muslims do not hold to this supposed prohibition, and even among those who do, interpretations of the precise meaning and purpose of the relevant phrases in the hadith literature are diverse. (On this topic, see here.

But there are other reasons for resisting the argument that the cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo were somehow responsible for creating the climate of extremism that led to this incident. The more I learn about the work at Charlie Hebdo (and I admit I have more research to do in this regard), the more I am convinced that this implication is unjust and unfair.

I am a British-born academic who has lived in the United States for over two decades; I am largely ignorant of contemporary French culture, and I confess I am only now becoming even superficially familiar with Charlie Hebdo (just like most of us, I suspect). But from what I have been able to ascertain in my preliminary investigations, while the cartoonists at the magazine were commenting satirically upon religious extremism, they were not creating it. The extremism was already there. They were calling it out — perhaps in a foolhardy way, perhaps courageously, and with varying degrees of mean and clever wit — but they were reacting to something that was already present in the culture, and that was being fostered by even more negative, reactionary, and ill-intentioned forces based outside France. (Indeed, no matter what one thinks of the Charlie Hebdo cartoons, any role they could have played in radicalizing these particular terrorists is surely outweighed by Said Kouachi’s months of training in Yemen under a branch of Al Qaeda.)

Nor does it seem correct to accuse the editors at Charlie Hebdo of racism, as some have done. Experts who are better informed than me with regard to the history and culture of French comics (the brilliant Bart Beaty, for example) tell me that, on the contrary, the editorial position of the magazine was consistently anti-racist. This is not to say that a case against individual cartoons could never be made; caricature is an art-form built on principles of exaggeration and abstraction, and the point at which the visual “shorthand” of the cartoonist becomes a stereotyping technique cannot be fixed, but will vary from situation to situation and viewer to viewer. Nevertheless, any such case would have to be made within the larger anti-racist intentional context of the magazine, and nuanced accordingly. I’ve yet to read such context-sensitive work; it is not a feature of those denunciations of Hebdo as “racist” that I have seen. Nor does there appear to be any evidence that the editors at the magazine regarded the Muslim community in general with hostility. In fact, there appears to have been at least one person of Muslim heritage on the staff at Charlie Hebdo who was killed in the attacks: Mustapha Ourrad, a proofreader.

Yes, Charlie Hebdo published work that was profoundly hostile towards religious extremists within Islam; it was similarly hostile towards other religious authoritarians, too (which is probably why rightwing Catholics like Bill Donahue have been willing to suggest that the cartoonists were essentially asking for it). Indeed, the general stance of the magazine appears to have been one of gleeful contempt for religious and political hypocrites of all stripes. Certainly, the boost that explicitly racist politicos like Le Penn are currently seeing in the French polls in the wake of these events would have horrified Charlie Hebdo’s editor Stephane Charbonnier, a life-long left wing activist who was (according to the New York Times) raised in a family of French communists. In fact, I think Charb would be commissioning some bitterly ironic anti-fascist cartoons in the wake of the current xenophobic rightwing groundswell — if only he were here to do so.

In other words, the cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo seem to have been exactly what you might expect satirical cartoonists in the French tradition to be: mockers of pomposity and demagoguery of all kinds.

I think I understand the motivations of at least some of the critics of Charlie Hebdo, even if I do not agree with their assessment of the magazine. They are concerned, rightly, that Muslims of good will should not be held responsible for these crimes or bullied into silence; and they are concerned, rightly, that ongoing incidences of the victimization of Muslims in France, Britain, America, Palestine, and elsewhere should not be overlooked or worse yet, justified, in the wake of this outrage. And they are right because at a time like this it is obviously very important that Muslim voices (in particular) are heard, in all their diversity. Indeed, it is absolutely necessary that Muslims of good will should be welcomed to the table, so that we can repudiate vile, greedy fools like Rupert Murdoch when they spew their poison and ignorance into the world.

But surely it must be possible to include Muslim perspectives on this kind of violence without accusing the cartoonists of Charlie Hebdo of political insensitivity (a criticism that seems to misunderstand the very point and purpose of satire), let alone deliberate racism (a charge that thus far appears to me unjustified)? Instead, and perhaps more productively, we could chose to emphasize that a man of Muslim heritage worked and died alongside the cartoonists at the magazine; that another Muslim man, a police officer named Ahmed Merabet, died defending the cartoonists at the magazine; and that yet another Muslim man, Lassana Bathily, saved several hostages from another terrorist at a Kosher grocery the next day. If we keep reminding people that members of the Muslim community were victimized here, and others also acted heroically, that will go some way towards making the reactions of people like Murdoch seem absurd, and make productive dialogue between social groups more possible.

In sum, and while there is no doubt much more that could be said, I think the suggestion that the cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo are in any significant way culpable for the climate of extremism that led to these tragic events is unfair not only to those cartoonists but also to the many members of the Muslim community who would never in a million years respond to a cartoon — however offensive they deemed it — with a bullet. It also just puts the cart before the horse. After all, if a right wing Christian were to shoot Andreas Serrano for making “Piss Christ” I would not repudiate blasphemous artists for unnecessarily provoking radical Christians; instead I would ask what forces were at work to make some Christians feel that murdering artist-provocateurs was a necessary and acceptable defense of their faith. I wouldn’t think the act was somehow the responsibility of Christians everywhere, but neither would I blame Serrano himself — for all that “Piss Christ” is more readily legible as a desecration of a religious icon than any of the cartoons at Charlie Hebdo I’ve seen. (And I am aware that Serrano himself declares the work to be devotional.)

I write these remarks in the hope that they will be interpreted not as an attack upon those with whom I disagree, but in what I hold to be a spirit of fairness both to the dead and to the living, of all faiths and of none.

_______

For all HU posts on Satire and Charlie Hebdo click here.

” This is not to say that a case against individual cartoons could never be made; caricature is an art-form built on principles of exaggeration and abstraction, and the point at which the visual “shorthand” of the cartoonist becomes a stereotyping technique cannot be fixed, but will vary from situation to situation and viewer to viewer.”

This sentence makes me squirm. It is about the most weaselly thing in the entire piece.

Charlie Hebdo has been analysed is being analysed and labels are being issued. We can also analyse the Je Ne Suis Pas Charlie argument and issue labels too.

In an academic analysis one expects certain standards. Firstly in the Je Ne Suis Pas argument a certain list of cartoons was selected for highlighting. The question is in selecting those cartoons for highlighting how many other cartoons had to be seen and discarded from selection.

Now we have two piles of cartoons a very small pile that were selected in order to carry the Je Ne Suis Pas Charlie argument and a much larger discarded group of cartoons. Now I suggest we consider that much larger pile of cartoons that were seen but discarded – and ask what could that pile of cartoons tell us – do they tell a different story and did those that deselected them know what that story was?

In addition the small pile of cartoons that were selected were interpreted in one way – without presenting the current affairs context for those cartoons and without presenting the interpretations of those that produced the cartoons and those that knew about those cartoons.

All this suggests that in gathering the evidence for the “CH = racist islamophobe” argument – that data gathering process was biased and the presentation of that evidence was biased. From these biases one can begin to assign labels to the Je Ne Suis Pas Charlie phenomena.

Other interesting structures to the Je Ne Suis Pas Charlie campaign can be assessed. I have been interested that one of the policemen that died has been selected from the seventeen victims as part of a “Je Suis Ahmed” alternate flag for a group of the JeNeSuisPasCharlie campaigners. One can ask what were the thought processes involved in choosing Ahmed rather than any of the other 16 victims. Three people died for their role of law enforcement in this murderous act but out of those three only was selected for their campaign.

Ben wrote: “Most troublingly, to imply that the cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo contributed to the radicalization of Muslims by repeatedly violating an important tenet of Islam reduces the wide range of Muslim opinions on this specific issue to the extreme position held by the terrorists themselves. To take up this position is to fail to understand that the so-called “prohibition against images of the prophet” is actually already a radical interpretation of Islamic doctrine.”

I think this is one of the most insightful and honest assessments I’ve read regarding the entire issue.

Hi Ben in your article you present recent events in Paris as the plural of tragedy rather than as the singular. Would you care to elaborate on that as I think many would have used tragedy in the singular rather than in the plural.

Correction– its Marine Le Pen, not Le Penn.

Ben, this is a thoughtful and really well argued and written piece. Thank you for writing it– just yesterday I was asking the universe for a well considered piece supporting Charlie Hebdo. However, I agree with Dave Gray that the quick description of caricature is very, very problematic. To draw Mohammed as any race other than Middle Eastern would be absurd, yes, but to lean on ‘hook nose’ and ‘crazy eyes’ visual shorthands becomes offensive.

I am not vouching for censorship, but acknowledging that this stereotyping was a deliberately offensive move on the part of Charlie Hebdo. And, one that erases the very diversity and breadth of Muslim experience that you are writing about. Of course many different people who practice Islam have many different reactions to Charlie Hebdo, to the prohibition to show Mohammed, and to the radicalization and militarization of their faith.

But that wasn’t what Charlie Hebdo had dedicated their magazine to demonstrating and supporting. Instead, they dedicated their magazine to conflating Islam with very Orientalist, very offensive imagery and ideas, reflected not only in their cartoons but in their reporting and editorials. They were not exclusively do this, but they did this a lot of the time.

I wish people could support Charlie Hebdo while honestly saying, “Yes, I understand that Charlie Hebdo was regularly using established racist imagery to conflate Arabic people and Muslims, and to make the figurehead of their faith look like a hyperactive lunatic. Moreover, I believe there is a time and a place and a use for that racist imagery, as Charlie Hebdo demonstrated.”

Most won’t be able to say this, because it would take a rather incredible amount of courage. This is sadly due to a state of affairs where using the word ‘racist’ escalates any conversation to a nuclear state, like the n-word, or ‘Nazi.’ I don’t think the word racist should be treated with such kid gloves, or consider people who do racist things as automatically evil, because we need to accept and analyze the racist things many people do on a day to day basis. David Brothers argues this much more coherently than I do here.

You can decry, and mourn, the attacks, as I do, without having to defend this magazine. I don’t think the editorial staff were evil people– I know very little about them at all! But I do think what they were doing was oftentimes racist.

Ben, thank you again for the piece, and for taking the time to read this comment. I know it is written in an urgent tone of voice, and I don’t mean to start a fight, and I do really appreciate your point here. I also DO NOT mean to call you racist, or meant any part of it to imply that you are. I just really can’t see these images as not being racist. I wish you had explicitly defended them as NOT being racist, if you think they are not.

Charlie Hebdo uses caricature as part of the satire. The important thing is to view Charlie Hebdo as part of an ongoing communication using satire as part of the medium to convey the dialogue. The thing is in communication you have to decide on words and symbols as referents and while claiming this symbol should not be used for reference you need to present alternate symbols to be used otherwise you end up closing down that speech and communication and before you know it we are in an authoritarian state.

Joyce, criticizing someone’s use of imagery (racist or otherwise) really is not a slippery slope to authoritarianism. Nor does criticism have to be constructive. A critic is allowed to look at a finished piece and say, this doesn’t work (or even, this is racist.) That’s part of free speech. It’s not a contradiction to free speech, nor a threat to free speech.

Putting aside kooky claims of slippery slopes to “authoritarianism”, I challenge anyone to look at the Charlie Hebdo cover with the Boko Haram women and deny the image is racist, and blatantly racist in any context in which it would or could be read.

That is why the obfuscatory language in this article, with its vague references to “individual cartoons” and “situation to situation”, is so frustrating. Maybe in the context of 1940s newspaper comics someone could claim a different meaning for that image, but in contemporary times that dog doesn’t hunt, which is maybe why this article seems so ready to paper over those “individual cartoons” that cause its argument trouble.

What I also find missing from these discussions about context is, well, context: how the social conflict in France over “Muslim” immigrants is pretty much completely racial, and involves far more French xenophobia toward Arab immigrants, specifically, than it does hostility toward Muslims as a religious group. Anti-Muslim legislation in France (and its supporting material in the press such as Charlie Hebdo) follows the same pattern as English-only legislation in the United States: it is demagoguery for racist political constituencies.

“I challenge anyone to look at the Charlie Hebdo cover with the Boko Haram women and deny the image is racist, and blatantly racist in any context in which it would or could be read”

This has already been done in the numerous responses to the Je ne Suis Pas Charlie campaign. Don’t ignore it, recognise it and agree to disagree but don’t assert your interpretations on me and don’t assert you have access to an absolute truth.

The way I see the Paris “tragedy”:

One incident of racism: the murder of 4 jews for being jews.

One incident of extremist ideology: the murder of 10 satirists.

Two incidents of power assertion: the murder of 3 law enforcement officers.

The JeNeSuisPasCharlie campaign has become something else not directly related to the Paris situation. This is my opinion and I think I have a valid opinion.

I really struggle with the idea that if I knew the proper context of these cartoons they would cease to be racist.

Is Birth of a Nation any less racist because of the context within it was created a hundred years ago? Are the portrayals of Jews in Ivanhoe or Fagin in Oliver Twist any less racist or stereotypical because of when they were written? Are the propogandist images of Jews during 1930’s and 40’s Germany okay because anti-semitism was just a way of life back then?

It seems to me that there is a big difference between saying that a portrayal is a product of its time and allowing for a change of perspective over the years versus exonerating it because its context excuses its offensiveness. Especially images that are purposefully offensive, whether satire or not.

And while I allow that some things are lost in translation, it seems to me that if each and every racist cartoon has to have the context explained to me so that I can understand why it isn’t racist, it is failing in its attempts to be effective satire.

The subject of racism is interesting but I think it is separate to the incidents of murder that occurred in Paris.

The JeNeSuisCharlie Campaign has become by some an assertion that the 10 satirists that were murdered were racist – islamophobe and Charlie was racist – islamophobe. There are now two opinions. One is Charlie is racist and the other is Charlie was not racist.

Racism is a separate issue. If we were talking about it I would refer to Wittgenstein. Imagine for the sake of argument a black man calls another black man a n*****. Is that racism? I think this argument can be used to show that context has to be taken into account when dealing with claims of racism.

Sure, context has to be taken into account. No one’s denying that. the question is which contexts, and what do they mean?

As far as how the cartoons are seen outside France, maybe an example of a different context would be Cumhuriyet in Turkey reprinting some CH cartoons, in opposition to what they see as government islamisation of the state?

Hard to evaluate while its still playing out, but it seems some Turks see a value in the cartoons which maybe French muslims of Turkish descent don’t?

Let the last word on the subject of Charlie Hebdo come from a one-time editor of the magazine, who sent his former colleagues this cri du couer in response to a op-ed piece in Le Monde written by ‘Charb’ (one of CH’s slain cartoonists) in 2013. This is a translated reprint of Olivier Cyran’s response to Charb’s opinion piece, justifying his magazine’s putrid and hypocritical stance on Muslims (all in the name of anti-racism, of course). Like this paragraph:

“You claim for yourself the tradition of anti-clericalism, but pretend not to know the fundamental difference between this and Islamophobia. The first comes from a long, hard and fierce struggle against a Catholic priesthood which actually had formidable power, which had – and still has – its own newspapers, legislators, lobbies, literary salons and a huge property portfolio. The second attacks members of a minority faith deprived of any kind of influence in the corridors of power. It consists of distracting attention from the well-fed interests which rule this country, in favor of inciting the mob against citizens who haven’t been invited to the party, if you want to take the trouble to realize that – for most of them – colonization, immigration and discrimination have not given them the most favorable place in French society. Is it too much to ask a team which, in your words “is divided between leftists, extreme leftists, anarchists and Greens”, to take a tiny bit of interest in the history of our country and its social reality . . .” ?

*But of course, some of you will consider my refusal to uphold CH’s ‘humor’ as a fearless and vanguard stance as some sort of endorsement of censorship. CH had (and has) the right to publish whatever it likes without any argument from me advocating limits on free speech. But for those of you who insist that we all wholeheartedly endorse its editorial content as a way to condemn the mass murderers responsible for these deaths, I suggest you look at the real world consequences of CH’s success in getting leftists in lockstep with Europe’s increasingly hard right policies. Muslim women, who have always been vulnerable to violence at the hands of right wing thugs, now face an uphill struggle for even basic rights, thanks to the kind of policies CH’s editors endorse that have resulted in women in headscarves being ejected from cultural spaces, and now even forbids them from performing public service – all in the name of the bougie-feminist left that unites the non-competing interests of Marine Le Pen with Femen’s topless activists. CH’s editorial stance could be summed up as ‘Freedom of speech for the powerful by the influential and irresponsible – at the expense of the powerless’.

The biggest problem with all of the “Charlie Hebdo is racist” pieces is in the timing. Many of us….most of us outside of France, I would wager, had never seen these cartoons, read Charlie Hebdo, or even heard of it, before this tragedy. The only thing that has folks writing about CH is the fact that people were killed. To then come out a week later and write opinion pieces saying that “those [dead] people” were racist is going to have the scent of “blaming the victim”–even if the writer of said piece explicitly says “nobody should die over these racist images.” In fact, people DID die already and to then point out their racism (even if true…which I don’t feel sufficiently educated in the context to say) is to kick people when they’re dead. Certainly, it is within our rights to critique racism, in the name of trying to obliterate it, in defending the rights of Muslims, immigrants, and other oppressed groups, etc. However, to start the process of critique and accusation after those accused have been brutally murdered is just not that productive. If such critiques were made before the event, then certainly those critiques stand and still exist, but for the media vultures (most of whom never gave a thought to CH before the events) to descend upon (literally) the corpses in order to get clicks, web hits, or paying readers is more than a little distasteful. People, of course, have the right to say what they please (as did the creators of CH), but all rights do not need to be constantly exercised.

The comparison to the Rushdie Affair (made by somebody in the other thread) is interesting. Satanic Verses is a book whose “main plot” is a substantive critique of the ways in which Britain in the 1980’s viewed and treated immigrants, and particularly Muslim immigrants (of which Rushdie was one). At the same time, the novel is intentionally provocative towards “radical Islam,” Iran’s Ayatollah, and religious fanaticism. Not only does it depict the prophet, it depicts him as a very flawed individual, the Koran as a text altered and edited by corrupt men (and not the unaltered word of Allah as transmitted directly to his prophet), etc. It also portrayed a harem of prostitutes who used the names of the prophet’s wives as a means of exciting men who were violating taboos. Given that Rushdie was a Muslim immigrant, and the content and context of the book, it would be difficult (it seems) to accuse Rushdie himself of “racism” based on opposition to Muslim immigrants, yet Rushdie was, of course, targeted with the kind of violence visited upon CH (and accused of racism by many who didn’t bother reading the book). Rushdie opposed his perception of radical/fanatical Islam with his own vision of liberal/secular/democratic black Britain (and, perhaps marginally, Islam)…and was persecuted as a result. I’m not exactly sure what this tells us about the CH events, but there are definitely some parallels that suggest this is not some kind of simplistic racial issue (or a simplistic post-9/11 issue, given the pub. date of Verses–1989). Verses is not CH, and CH is not Verses, but they do share some context.

So…the problem is that you’re missing a step in the timeline, I think.

You have the narrative as — hideous act of violence occur against cartoonists, people descend to say, this art is racist.

But actually there’s a middle part.

Hideous act of violence against cartoonists.

People start saying, I stand with these people, and also start circulating the images as an act of defiance.

Then some people respond by saying, I resent being told that I need to identify with these images, because to me these images are racist.

Maybe that last bit is wrong. Maybe when people start saying “I am Charlie”, and circulating images with caricatured Islamic features, the response is to just say, well, people died, it’s not for me to respond to this, I should just either say, “I am Charlie” also, or I should be quiet and maybe just go off social media for a while.

But if that’s the argument you want to make, then I think you need to make that argument. The one you’ve got up there misses a certain amount of detail.

I would say that the “I am Charlie” thing isn’t good if it’s accompanied by racist images (and to start chanting “I am Charlie” without really having any connection to (or knowledge of) CH before the events seems problematic)….but to me the problem is a typical problem of the internet and social media era, which is that as soon as something happens, everyone has to have something to say (“I am Charlie”—“I am not!”) when most organs of public debate (to say nothing of people on twitter) have no clue what they’re talking about. This is the era in which we live (and now I’ve gone and done it myself), and it’s a good one in some ways. I wouldn’t call this one of them.

Maybe both the rejection embrace of Charlie Hebdo betray an enormous lack of context.

Someone mentioned that a cartoon was racist because it had a hooked nose. Does that mean hooked noses are racist? What if someone met a person with a hooked nose – would they point to that persons face and say you have a racist face?

So I think to myself what the ‘ell is wrong with having a hooked nose? Why the ‘ell do you perceive a hooked nose to be racist?

Charlie Hebdo is the perfect repository — a teensy little jar that holds one crocodile tear.

Noah, I am commenting here, as you indicate this is a better place to do so. Let me rephrase. Franklin makes a case–let’s forget about whether it’s a good case or not if you disagree–that Jacob believed he was being objective. As far as I can tell, you make no case, you simply assert your opinion that you doubt Jacob thought he was being objective. I’m aware that I’m a new guest here, I’ve been trying to gauge the scene in these parts, and I’ve been very impressed by some of your moderation. But it strikes me as pretty extraordinary to make that claim, that Jacob probably doesn’t think he’s being objective, and offer zero explanation. And your response to Franklin looks an awful lot like what I believe you would call a rhetorical move.

Eric, you should watch what you say. Sentiments like ‘one might not want to “kick people when they’re dead”‘ have been interpreted to mean — not approximately, but exactly — “white cartoonists should never be criticized.” Indeed that was the cornerstone of Jacob’s article.

And what’s especially interesting about this and allied claims — i.e., that your words are racist, that the cartoons are racist, that the cartoonists are racist — are themselves immune from any form of criticism or counterargument that (like Ben’s) refers to intention, purpose, or meaning. The only thing that matters is “effect” — the effect it has on readers, and by extension the way it is affected by “systems” of power. This is how Rushdie’s politics or ethnicity could be viewed as racist or Islamophobic.

This is not to say that argument-from-effect is invalid, or that argument-from-intent trumps all. But here’s my problem: from the former effect-driven point of view, statements like Ben’s that refer to purpose and meaning are — no matter how substantive or lengthy — almost literally beside the point.

The jehadis are playing the Western media and intelligentsia like a violin … once again.

Sasha, again, we can agree to disagree. Which should be fine, because you don’t think your view is objectively correct, right?

Joyce, I appreciate the clumsy parody of post modern relativism. Nicely done.

Peter, I love you, but I’m finding it hard to take this last seriously. Who exactly has called Eric a racist? He’s on a thread by someone who agrees with him, and most of the commenters seem to be in general agreement (I’m not exactly, but I don’t see where I called my brother a racist.) You seem to be creating a melodrama where you’re somehow an oppressed minority lonely voice of truth, or some such. Why do you feel you need to do that? Do you really feel that under assault on a comments thread in which many people take your side? What’s with that?

Your description of the cornerstone of Jacob’s article seems garbled beyond recognition, to me, I have to say.

The whole “intent” thing seems like a red herring too. I’m pretty sure that CH cartoonists were aware of the history of racist iconography they were using. What they thought they were doing with that is obviously open for debate, but either way, the question of intent is not being set aside (at least in this instance.)

I mean, I think people can accidentally reproduce racist tropes, and yes, those tropes are still racist even if folks reproduced them without knowing what tradition they were using. But no one is saying that’s what’s happening with CH, I’m pretty sure.

As I said, it’s totally fair to call something out as racist, and even productive to do so in many instances. I even think discussion of potential racism in the CH cartoons could be a useful thing to do in certain contexts. I was calling into question the time and place of such accusations. But, truth to tell, I feel like I commented here in a moment of weakness. I know that whatever one says about this issue will lead to castigation and condemnation (“You’re a racist!” “You’re justifying terrorism!”) I’m not sufficiently well-versed in the cartoons or the controversy to really want to stick my neck out…yet I hit send (actually “add comment”). Probably a mistake.

I don’t know…no one’s castigated or condemned you thus far… Peter’s said that someone would, and you’ve said that someone would, and maybe someone will, but hasn’t happened yet…(unless you count your self-condemnation.)

Noah, it’s not clear to me why you impute opinions to people that they haven’t expressed. In fact, when I say you make zero case to back up your assertion, I believe myself thoroughly objective. I would be happy to agree to disagree if there were something with which to disagree beyond a flimsy statement of opinion; as it is, I am left with the strong feeling that you are just being evasive.

Sasha, again, we can agree to disagree. Which should be fine, because you don’t think your view is objectively correct, right?

This is the kind of glib non-answer that makes it seem like you’re too good to answer legitimate objections to what’s going on here at HU.

It’s the sort of answer that makes it seem like I think the particular objection is glib and stupid. Which I do.

So we’re even in our assessment of the other’s glibness and stupidity. Equality for all.

Noah, I think I have garbled my intent so badly that it may not be worth trying to straighten things out. The claim about Eric’s comments was made with a partial wink. Of course no one has or will make this accusation. However, it is based on Jacob’s own assertion that Tom Spurgeon’s Tweet, which called for people to withhold their critiques till the bodies were cold, was a central — and perhaps only — piece of evidence in his claim that White cartoonists were being declared off-limits to criticism.

The second paragraph was simply a riff on the question of intention. In the face of Ben’s essay, which depends a lot on intention and meaning, I tried to point out that such arguments would hold almost no water with many forms of anti-Charlie criticism. Intention is, almost literally, meaningless. Structure and effect create meaning.

So all told, my opening was mainly a joke, poorly told and/or conceived. I’m sorry for that. The latter section was serious, or at least a serious attempt to think broadly (and invidiously) about the two types of criticism and rhetoric at work of late.

Argh. Sasha, I’m not imputing opinions to you. I’m making fun of you.

You think your opinions are objective. Yet somehow if Jacob thinks his opinions are objective, this is a thought-crime?

This whole conversation is incredibly stupid and is making my head hurt. People think their beliefs are true, otherwise they wouldn’t be beliefs. That doesn’t mean people think their beliefs are “objectively” true in the sense that “2+2=4”. You can make truth claims, and believe them, without making some sort of absolute appeal to objective truth.

The attack on Jacob for “objectively” believing whatever is just a way to turn a disagreement into a category error so you can feel justified in condemning him more strongly. You don’t like what he said; you don’t like his tone. That’s fine. Bringing objectivity into it seems kind of ridiculous, but if that’s the way you want to say what you want to say, that’s fine I guess. Whatever.

“It’s the sort of answer that makes it seem like I think the particular objection is glib and stupid.” Actually no, if that was your aim, you failed. It’s the sort of answer that makes it seem like you are unwilling to take a stand on the content of Jacob’s piece.

Peter…ah, okay. Sorry; I wasn’t following.

Eric, I am sorry that I implied that your statement about timing would honestly open you to attacks. I seriously doubt that it will or might. It just put me in mind of Spurgeon’s Tweet, which was a main target in HU’s seminal essay.

Rule 1: don’t Tweet.

Rule 2 (for me): don’t comment.

Take care,

Peter

No, Noah, I don’t think it is a thought crime for Jacob to think he is being objective. I believe he thinks he is being objective, and the content of his piece should be addressed with that in mind. I was simply mystified that you claimed he probably didn’t think he was being objective.

It’s the sort of answer that makes it seem like I think the particular objection is glib and stupid.

You didn’t think the objection was so stupid when you initially lobbed it at me. Seriously, you told Sasha to come over to this thread to comment just so you could tell him that?

I’m happy to take a stand on the content of Jacob’s piece. I think that his main point (that you can think and say that the comics are racist without condoning the violence against CH) is correct. I think he’s correct that the comics are racist and Islamophobic in at least many respects; I think they use a tradition of caricature that is racist, and they use it in order to offend (some) Muslims. I disagree with some of his points; I don’t think it’s true that the most generous interpretation possible would see the work as racist (obviously lots of people don’t see it that way.) I wouldn’t call the editor a racist asshole based on the given quote.

I don’t think his arguments have been somehow absolutely or thoroughly disproven by further context, though again I don’t myself agree with everything he says.

Okay?

The whole racism argument today is so full of politically correct contradictions and caveats it makes me sick. I also take exception with this now widespread canon: Group A can criticize, make public observations about, or make fun of Group A, but if Group B or Group C does the same thing, they are being racists. Worse, in some cases, such discussions — even innocuous ones — are being labeled as “hate speech,” and come with a felony charge.

That’s bullshit.

In California, one of their hate crime laws makes it a felony to “Desecrating a religious symbol or displaying a swastika on another person’s property with the intent to terrorize another person.”

Which means that, depending on the prosecutor, publishing a cartoon desecrating a religious symbol is now technically a crime.

That’s bullshit times two.

Okay, thank you. I honestly was just trying to get you to explain your objectivity comment, which suggested a possible non-disavowal disavowal of Jacob’s piece. I have no idea where you got the whole thought-category, believing-oneself-to-be-objective-is-a-crime thing.

Russ, I’m not in general a fan of hate speech laws. But the vision of an American society in which the innocent are mercilessly persecuted by narrow-minded antiracism is not one I find super convincing.

“Which means that, depending on the prosecutor, publishing a cartoon desecrating a religious symbol is now technically a crime.”

Have you read some first amendment law review articles on the subject or are you just going from the gut on this one?

Sasha, I think the argument got tangled between you and me and Franklin. Sorry about that.

It’s completely understandable. I do totally agree with Franklin, but my focus was really just narrow there.

Okay?

Better late than never. That would have been a proper comment to make on Jacob’s post back when it would have been timely. As it s, people are still cleaning up after you.

Peter, I’d be sad if you never commented here! I think with highly charged issues like this there are going to be misunderstandings, but I hope that doesn’t drive people off permanently…

Plenty of folks objected to Jacob’s post in comments. I don’t make it a habit of putting editorial caveats in the body of people’s posts. I print lots of things I disagree with. (I disagree with this post, overall, as just one example.)

Thanks for the link Franklin. Cultural tensions between Francophones and Anglophones is an interesting topic. Do they still eat Freedom Fries over there?

The tragedy of this kind of DIY online publishing is that you appear to endorse anything you don’t expressly contradict. (This is one of the reasons why I finally restricted comments to email at Artblog.net.) So if basic errors of fact regarding charged issues go uncorrected and you allow your authors to set the rhetorical bar at, say, “racist asshole,” those in themselves are messages on your behalf. Your habit is not a bad one but circumstances called for an exception.

Regarding Olivier Cyran’s open letter that is posted everywhere to prove that Charlie Hebdo is racist, let’s note there was a reply by Zineb El Rhazoui, then journalist at CH; I couldn’t find a translated version but basically, she contests that CH was/is racist, and wonders why he is blaming only the French journalists to prove they are racists; after all, she is the writer of the articles against Islam that he is citing to attack the journal. She then explains how she had to flee Morocco because of the military dictature and of the Islamists. She also takes offense at his amalgam “Muslims = Arabs”. Here is the complete reply (in French):

http://www.cercledesvolontaires.fr/2013/12/22/si-charlie-hebdo-est-raciste-alors-je-le-suis-reponse-de-zineb-el-rhazoui-a-olivier-cyran/

It is not that simple.

Well, HU is pretty lightly edited, overall — and we tend to often print things from contradictory points of view.

I don’t know that the letter is necessarily posted to prove that CH is racist. The point is that the suggestion that the publication is racist is not some sort of failure of context, or Anglophone mistake. These debates occurred in France as well.

There is a labelling aspect to terrorism. That is why one needs to take care when assigning certain labels. It is an occupational hazard for paediatricians.

The je-suisers argument is getting better…but it is still not there yet. Here are the intractable problems that remain:

a) “They were calling it (extremism) out — perhaps in a foolhardy way, perhaps courageously, and with varying degrees of mean and clever wit” The problem is: why should CH think that their white privileged voices would be perceived, or needed, by the Muslim community, to “call out” extremism. I don’t buy it. CH had been doing this for 45 years, to all right-wingers they didn’t like. They were simply angered by a new form of right-wing extremism being present in what they perceived as their country and reacted in a very foolhardy way indeed

b) “Experts who are better informed than me with regard to the history and culture of French comics (the brilliant Bart Beaty, for example) tell me that, on the contrary, the editorial position of the magazine was consistently anti-racist.” The problem is: it is not impossible to be anti-racist as an individual or small group and yet still to be part of the larger social problem of SYSTEMIC racism, as Du Bois argued a long time ago in his books The Philadephia Negro and The Souls of Black Folk. Ask Muslims in France: “how does it feel to be a problem”, Du Bois would have said.

c) “They (CH) are concerned, rightly, that Muslims of good will should not be held responsible for these crimes or bullied into silence.” The problem is: they should be cleaning up their own backyards before they start purporting to be in a position to clean up those of others. When encountering victims of racism, one must understand and espouse the role of ally, not of crusader. It is the voices of Muslims that matter, not CH.

d) “A man of Muslim heritage worked and died alongside the cartoonists at the magazine; that another Muslim man, a police officer named Ahmed Merabet, died defending the cartoonists at the magazine.” The problem is: Seriously? You are going to invoke tokenism as a defense? This only provides further proof of the points above.

e) “The suggestion that the cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo are in any significant way culpable for the climate of extremism that led to these tragic events is unfair.” The problem is: this is a red herring. The point is not to find CH to blame for the killings. The accusation of ‘blaming the victim’ is a red herring. CH definitely is a part of the extremist climate, and there is no reason why we have to uncritically swallow whole the CH version of their involvement.

f) Charlie Hebdo did not create radicalization; it already existed, they were merely responding to something that already existed. The problem is: this is again another red herring. No one holds the position that CH created the problem. On the other hand, they certainly accompanied it over 45 years and while radicalization got worse their rhetoric got more intense. One could say that they certainly didn’t cause it, but they also certainly didn’t cure it.

In many discussions you get some demanding answers to questions that have already been answered in the earlier discussion or explained in links to that discussion. Sometimes at the end of the day it is better to just state the differences of opinion and provide links to supporting arguments & evidence.

The other thing is that many of the answers can only come from those that were murdered. In such situations one should at least out of “respect” for those dead read what they wrote in defence of their own work before they were murdered – or at least read what those who are still alive and can speak for them have written. I believe that has already been done.

You don’t have to believe them. Fortunately we live in a society where we can agree to disagree.

In my ongoing attempt to not talk directly about Charlie Hebdo, I’m not 100% sure it is possible, at all, to caricature an ethnic/racial minority without at least coming incredibly close to racism. Caricature is a technique by which you simplify out everything but the most distinguishing physical details, which you overemphasize. Racism is discrimination based on some distinguishing physical detail that is overemphasized at the expense of everything else about the person. The artist who wants to use caricature in that context just has a really hard to get around problem.

“Racism is discrimination based on …”

and that’s the contextual … racism is “racism” if its discriminatory. A caricature is not inherently racist it only becomes racism if the caricature is part of a discriminatory context. So one needs to examine the communication in which the caricature was embedded within.

One needs to examine more than just the communication. The communication exists in a particular country, on a particular planet, in the midst of particular power relationships.

In criminal law intention is also an important criteria. We need to consider whether the intention was racist – see my clumsy parody of post modern relativism.

The range of things people define as discriminatory is extremely wide and extremely subjective. And in art, I think it is always centered on questions of “fair versus distorted representation.” Racist art never discriminates the same way that racist employers or racist hospitals or racist lunch counters do.

So when you ask if art is racist, you’re always asking whether it is a distorted representation. Satire is almost always a distorted representation – that’s also definition. So if you’re talking about this territory of race/ethnicity/minority group culture and satire and you add in caricature on top of it all, it is extremely, extremely hard to stay completely clear of this problem.

I gather that the cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo felt they were avoiding it because their work was so richly contextual and complex. But I also think that it was just as hard for them to manage this treacherous terrain as it is for anybody else, and I think that this tumultuous debate, including the anxiety over “je suis charlie” reflect that.

As for intention, in art, est-ce pas français?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Death_of_the_Author

There’s nothing “weaselly” about Ben’s argument. It’s all about NUANCE. It’s right to point out that the line between bad and good taste or decent and indecent, or offensive and funny is always culturally determined. Manicheans don’t want to know that.

* The analogy with Andreas Serrano’s “Piss Christ” work is completely relevant because it clarifies that cartoons are a legitimate artistic form and should be viewed as such. The outpouring of brilliant cartoons in the wake of last week only confirmed for me how border-free, alive and exciting this art form continues to be (much more so in my view than most of contemporary Western art which I find vapid)

* Another helpful analogy made by a commentator is with Rushdie’s “Satanic Verse,” for the same reason as above: offense was taken at a work of (literary) art, Rushdie’s critical depiction of a revered religious figure and the artist was punished.

* To add one more analogy for a meaningful conversation: what has been the reception of Art Crumb’s illustrated Book of Genesis? Can we study his representations of Christ, Adam and Eve to understand Crumb’s artistic choices, between realism and caricature for a Christian (or not) audience? I cannot help asking if it is a coincidence that Crumb lives in the south of France… I cannot help wondering if and how he would illustrate the Qur’an. See Crumb’s interview in the New York Observer and the cartoons he drew, and did not draw, in response to last week: http://observer.com/2015/01/legendary-cartoonist-robert-crumb-on-the-massacre-in-paris/

* The fact that the very existence of a publication like Charlie Hebdo is simply unthinkable in the American context explains to me why so many people in the US cannot really understand what has happened. In that sense, I feel David Brooks’ column “I’m not Charlie,” arguing that this satirical paper would not have lasted 30 seconds in the US, captures the sentiment of most Americans that the cartoons are/were offensive to the point of racism (see http://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/09/opinion/david-brooks-i-am-not-charlie-hebdo.html?_r=0)

The fact that the NY Times refused to publish Charlie Hebdo’s original cartoons or its current cover featuring the Prophet to explain to its readers the situation as well as the controversy it has sparked within the paper’s team and with its readers is revealing of a prevailing but unexamined self-censorship, (See http://publiceditor.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/01/14/with-new-charlie-hebdo-cover-news-value-should-have-prevailed/)

What is paradoxical for me is the fact that, whereas the US has a *much* broader understanding of freedom of expression than France (where there are several distinct restrictions), fear of litigation (more so than political correctness or security issues) has curtailed what everyone decides to print or draw. Charlie Hebdo, on the other hand, has been sued on average once every six months, close to 50 trials since 1992, from the far right to Muslim organizations. They won most of time. So what was the process until now? Charlie Hebdo offends->they are sued->the judge interprets the law->the law prevails. So I want to ask: what is wrong with this process? When extremists are frustrated by a legal process and take it upon themselves to do justice and execute whom they judge guilty, every society is in deep trouble.

* In one of the most thoughtful pieces I’ve read, the writer Saladin Ahmed makes the case that “in an unequal world, mocking all serves the powerful.”

See http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2015/01/10/when-satire-cuts-both-ways/in-unequal-an-world-mocking-all-serves-the-powerful. Indeed, if France achieved its goal of liberty, it is still sadly far from the equality it preaches because it is caught between its ideal of universalism (our humanity unites us, regardless of our differences) and the reality of its colonial past: millions of French citizens struggling to fit in, to belong, bearing the weight of this past, namely its racism, discrimination and exploitation. I am still waiting for a thoughtful sociological analysis of six of the lost lives, three victims/three gunmen that bears comparing:

1) Charlie Hebdo’s copy editor, Mustapha Ourrad, 60 years old. From the Kabyle region of Algeria (famed for his resistance against France during the Algerian war of independence). He’s been described as an “atheist Sufi.” His (autodidact) mastery of French literature, poetry and language had earned the nickname of Mustapha Baudelaire. He had received his French nationality a month ago.

2) a 41 year-old French Muslim “gardien de la paix” (literally keeper of the peace), Ahmed Merabet from the Seine Saint Denis suburb north of Paris (famously referred to by its 93 zip code in rap songs). He had just passed the exam to be promoted police officer. His parents came from Algeria; he had five siblings.

3) a 26 year-old black female municipal officer, Clarissa Jean-Philippe, from the French island of Martinique who was finishing her internship with Paris municipal police.

What choices did they make, what obstacles did they overcome, what support did they get to want to keep on living in France as French citizens inheritors of its colonial history? And how do they compare to the choices and obstacles faced by their killers, two French Muslim orphaned brothers (from Algerian parents) and a French Muslim black man, Amedy Coulibaly whose family came from Mali and who had nine siblings ? I think the first path to understand what happened is to examine these six lives and learn if and how and why France’s colonial heritage can be faced by its citizens.

To make matters more complex, France is still digesting another past, its history of antisemitism and the legacy of the Vichy Regime. The Jewish victims were targeted, a crime whose hatred rise from this Franco-national historical context coupled with an international geopolitical situation that plays itself out on French soil (be it the Israel/Palestine conflict; the US wars in the Middle East; France’s interventions in Mali and elsewhere).

Let’s keep in one’s mind *all* of the above *simultaneously*. It is huge. On the Richter scale of events, the magnitude of what happened last week in France is shattering.

Pallas — I’m going from the gut. I’ve been watching all of this unfold over the past couple of decades, and I don’t like the fact that we seem to be regressing, free speech-wise, than progressing. Hate speech laws — even if unenforced — have a chilling effect on free speech. And all of the qualifying statements I’ve been hearing from alleged free speech advocates — stuff like “Oh, the Charlie Hebdo staff had a right to free speech, BUT…” — is blaming the victim, not the criminal.

As I said in a different post, murder isn’t free speech “criticism” — it’s murder.

I think I meant see my two black men talking to each other analogy rather than the hooked nose relativism.

With regard to Barthes I don’t think his argument was peer reviewed by a high court judge.

Dear David:

Points a) and b) are well taken. I think you have misunderstood my argument at points c) and d), and I disagree with points e) and f). Whether it’s a red-herring or not in the grander scheme of things, a good deal of the “je ne suis pas Charlie” rhetoric seems to me to adopt a position of condemning the cartoonists, and this seemed to require some sort of response, however inadequate. I don’t have the confidence in my own moral and intellectual superiority to the men and women at the magazine who were killed that some commentators have displayed, which is why I’ve generally identified with the “je suisers”.

But perhaps both slogans are in the end unhelpful — forcing people to feel like they need to take up one side or the other. Clearly, matters are much too complex, painful, and multifaceted for that.

Right now it seems near impossible to address the tangled and painful issues of race, religion, secularism, and cartoon-hermeneutics without falling short; it certainly is for me. For what it is worth — not much, I know — my thoughts on the many issues exposed by these sad events continue to evolve, and the debates that have played out in these comments have helped me with that process.

So, thank you for commenting, and to everyone else who has commented, and to Noah for posting the piece. At this point, I think my ruminations have been entirely superseded by much better articles from numerous perspectives. I’d cite this one in particular as valuable for providing contextual information that I did and could not:

https://ricochet.media/en/292/lost-in-translation-charlie-hebdo-free-speech-and-the-unilingual-left

Joyce – my point is that the “charges” here are in the realm where Barthes is the appropriate arbiter, not a high court judge. This business of equating critiques of the cartoons with critiques of the cartoonists — whether it’s made by the readers of the critic or by the critic him/herself — is a fundamental mistake that is enflaming these debates unnecessarily.

That, I think, is a result of timing, as Eric rightly points out. But it is also the result of the unfortunate hashtag that was so quickly popularized. I wish there were a hashtag that more explicitly included, as Fabienne points out, the French police who were also killed. But instead the metonymy is made with the paper, with the cartoons – contra Barthes. The intentions of the cartoonists are extremely far away from the issues most relevant to people who critique the cartoons.

Hi Caro – does that mean in terms of the question of caricature being racist or not racist it is in fact both. Both sides can find themselves a position of fortification and lob rocks at each other. Of course it is inherently both then we look towards context to help in assessing intention (Barthes permitting)

I don’t think context resolves the problem. An artist could have a completely insidious intention but still manage to do something that worked ok in context, and vice versa (that is the point of the Barthes, is it not?)

Dear Fabienne —

Thank you for your eloquent and detailed comment. I could not agree more: the implications and reverberations of this event expose some genuinely staggering difficulties. Thank you so much for taking the time to respond. I’m so proud to have you as a colleague; Comics Studies at the UO benefits enormously from your expertise.

I see your point but I am not sure Barthes resolve the two black men analogy where one uses the word n**** to the other.

That’s not a question of representation, at least not as you pose it.

People claim that the English language is inherently sexist with gender pronouns. I think French is more so. One could analyse a literary work and potentially find it sexist because of the inherent sexism in the language. This is something many institutions have to be careful with – when using he/she her/him for a generic student etc.

Joyce, Tarantino did get a lot of flack for that issue in Django Unchained. In this essay he discusses it with Henry Louis Gates, Jr.: http://www.theroot.com/articles/history/2012/12/the_nword_in_django_unchained_tarantinos_explanation.html

That may be helpful for your question. The situation doesn’t seem all that relevant to me for the reasons I mention in my second comment up there.

Noah, don’t chastise me for not making the effort to remember how to put a link in these comments :D.

I think I should have avoided the Charlie Hebdo issue and brushed up on my wonder woman.

http://chiseler.org/post/108182628756/mohammed-sabaaneh