We are halfway into the month of January, and already the year 2015 has unleashed unspeakable violence – whether we look to the horrific massacre of the Charlie Hebdo cartoonists, police officers, and Jewish hostages in Paris, France or to the unimaginable carnage that left 2,000 villagers dead in the northeastern region of Nigeria. Both attacks were fueled by radical Islamists, including the infamous Boko Haram, who kidnapped over 200 schoolgirls last year, an act that helped launch the widely popular #BringBackOurGirls hashtag on Twitter. Yet, international outrage has galvanized massive support for the Charlie Hebdo victims with a #JeSuisCharlie movement rising to protect freedom of speech and other beloved Western principles, while a lesser movement is struggling valiantly to promote #AfricanLivesMatter, politically connecting this sentiment to another popular hashtag: #BlackLivesMatter.

While some may wish to de-racialize these narratives with the so-called colorblind #AllLivesMatter, the unequal attention to these world events simply reinforce that not all lives matter, least of all those who are not afforded the white privilege of the French journalists who were unjustly murdered – no matter what one may have thought about their questionable cartoons that seemed to racialize its French minority population of Muslims and people of color. Nonetheless, the memorialization of Charlie Hebdo reinforces how much more white lives are valued. That some took to Twitter to create #JeSuisAhmed, in memory of the Muslim police officer also killed in the attacks, is a gesture reminding us that the value of marginalized peoples is never taken for granted. As Noah Berlatsky noted, “Who is remembered and who is memorialized has everything to do with race, with class, with where you lived and who, in life, you were.”

Of course, we can rationalize inequalities in media coverage – why the “world” seems to care about France over Nigeria, or why English speakers are questioning whether or not the Charlie Hebdo cartoons are “racist” or not, or even if we should criticize murdered victims who can no longer speak for themselves. Perhaps the violence in Africa seems more “routine,” in comparison to what takes place in Europe, hence more focus on Paris. And perhaps English speakers are “misinterpreting” Charlie Hebdo cartoons as “racist” and “Islamaphobic” since we are not translating the French correctly. Yet, such reasons given seem to suggest an unequal flow of information, as if “African violence” and “Muslim irrationality” are the only acceptable explanations for why violence happens (and why we should care more about France than about Nigeria).

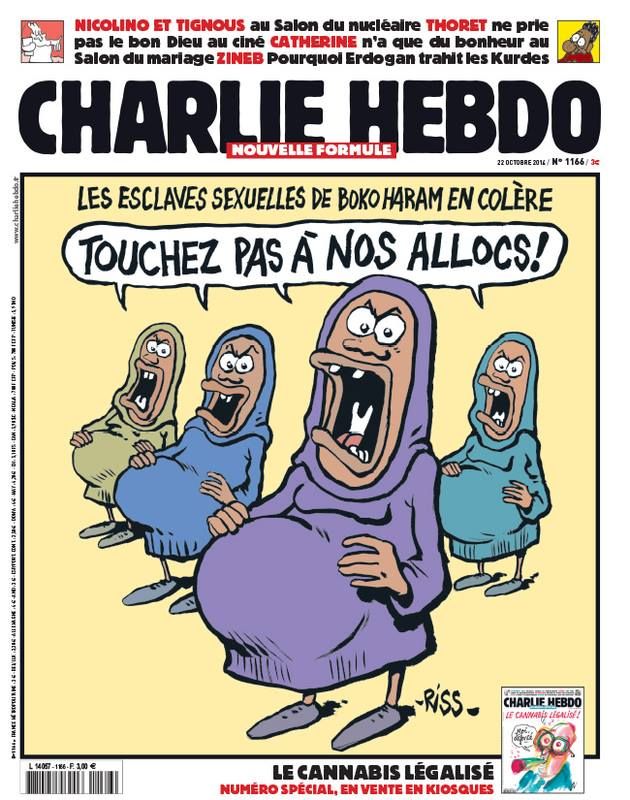

However, it is to these points that I want to take note of a particular cartoon featured in Charlie Hebdo, one that has drawn the most criticism for the publication’s racial politics. Here I refer to the cartoon depicting Boko Haram’s kidnapped girls in Nigeria.

As French-speaking translators have informed us, the text reads: “Boko Haram’s sex slaves are angry,” while the visual depicts head-covered girls yelling “Don’t touch our welfare!” And as Max Fisher suggests, the cartoon functions on two layers: “What this cover actually says … is that the French political right is so monstrous when it comes to welfare for immigrants, that they want you [to] believe that even Nigerian migrants escaping Boko Haram sexual slavery are just here to steal welfare. Charlie Hebdo is actually lampooning the idea that Boko Haram sex slaves are welfare queens, not endorsing it.”

Such explanations may provide us with contexts and subtexts, but they are nonetheless steeped in apologia, conveniently overlooking the visually demeaning drawing of the girls or the racialized subtexts associated with African or Orientalist sexual savagery, coupled with a transnational narrative of black and immigrant women unfairly using the state’s resources (how interesting that conservatives here and abroad tend to speak the same racial language). Regardless of Charlie Hebdo’s own politics, the visual narrative recycles stereotypes and could easily be appropriated for white supremacist narratives.

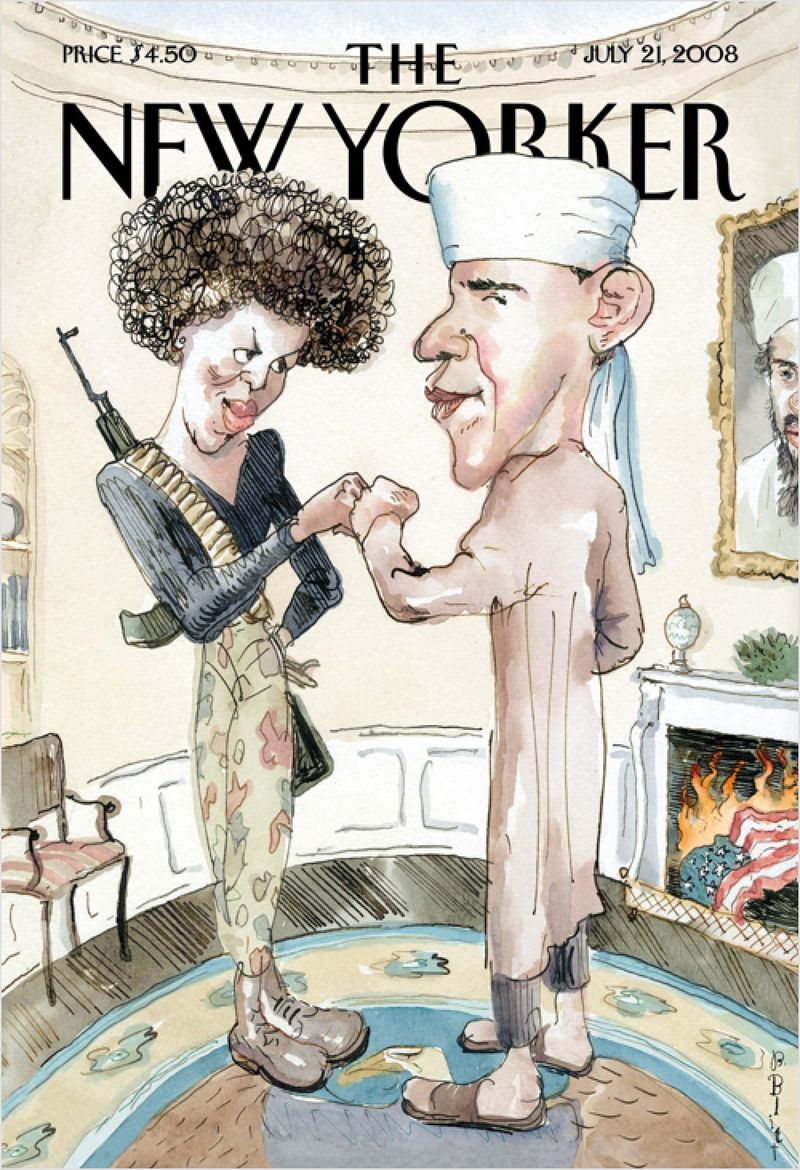

Fisher juxtaposed this satire alongside another parody – the New Yorker’s satirical takedown of Republican fears of the Obamas’ “secret black nationalist Muslim” plans during the 2008 presidential campaign.

Fisher then argued that “most Americans immediately recognized that the New Yorker was in fact satirizing Republican portrayals of the Obamas, and that the cover was lampooning rather than endorsing that portrayal.” This really highlights the problem of unspoken white privilege and power, as Fisher conveniently forgets that the New Yorker too came under attack – especially from communities of color who saw in the satire a failed use of racial imagery to poke fun at racism.

Why is it that the black or brown body becomes the vehicle for racial humor when the objects of ridicule – the white people presumably targeted for their racial bigotry – remain invisible in these satirical narratives? When recycling racial stereotypes – which both The New Yorker and Charlie Hebdo have done – do linguistic texts and subtexts hold the same equal power as the visual text, which holds heavier historical weight? Not all members of society (specifically communities of color who continue to feel their marginality in various social institutions) read these visual narratives in the same way. After all, if even in the U.S. certain Americans didn’t find the New Yorker cover funny – though we speak the same language and have access to the same cultural and political frames of reference – then what gets “lost in translation” when exposed to other local texts, contexts, and subtexts? Whose voices remain silent?

I specifically think of this when considering the actual creation of the Charlie Hebdo Boko Haram cartoon. I have a difficult time imagining a black woman cartoonist of any nationality – French, British, American, Nigerian – creating such a cartoon in jest. I also have a hard time seeing such a woman hired by the staff at Charlie Hebdo, and even if she were and found the courage – as the sole “token” black woman at the paper – to speak up to her colleagues and say, “Hey guys, this cartoon isn’t funny, and here’s why,” would her white male colleagues let her speak? Would they hear what she had to say? Would they drown her out with their insistence on “free speech” and “the right to offend,” or would they sincerely listen to suggestions on how their takedown of French political right racism could be, you know, clever (as racial stereotypes never are) and how the offense could be more effective in a “punch up” or “punch across” rather than “punch down” kind of way?

And therein lies the problem: the unequal flow of perspectives and unequal participation. Whether we point to white conservativism or white liberalism, these narratives hold cultural weight, even those that insist – because they may be on the “right” side of antiracism politics – that they could never get their racial politics wrong, even when they don’t interrogate the ways that they may hold or perpetuate racial privilege and power. The views of others remain in the margins, including our pain and suffering.

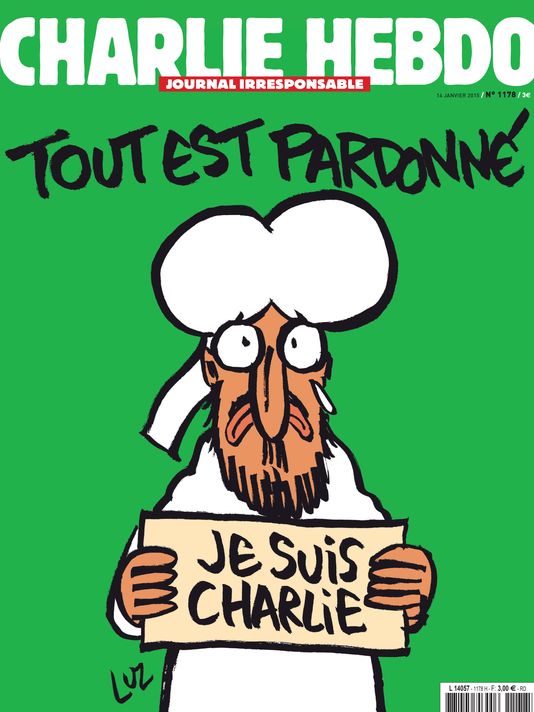

Charlie Hebdo’s latest cover features the Prophet Muhammad holding a “Je Suis Charlie” sign with a single tear rolling down his cheek as the text reads “All if forgiven”; the satire is quite apt and heartfelt and, most importantly, captures a kernel of truth in the moment.

On the other hand, the Arab stereotyping of the prophet distorts truth and has reconstituted him as a French creation of the cartoonists’ own making, no longer connected to the religion or culture that prompted their satire in the first place. That is the nature of stereotypes, which have the effect of erasing altogether the very peoples and cultures they were intended to represent.

In closing I want to return to the scene of Nigeria, in particular Boko Haram’s alleged use of a ten-year-old girl to carry out a suicide-bombing attack. I can’t help but think this is the most cynical ploy and a deadly play on satire. What else is Boko Haram expressing but their utter contempt for and mockery of the West’s “Bring Back Our Girls” movement? They implicitly know that our rhetorics are empty and our raced and gendered messages constantly show our disregard for women and girls of color. They know that black girls’ bodies will only serve as mere objects of parodic visuals or Twitter hashtags without any real actions demonstrating that their lives matter. Somehow, these global understandings of whose lives matter don’t get lost in translation.

________

For all HU posts on Satire and Charlie Hebdo click here.

This made me think of this http://pastebin.com/zAB0Pv8a – a translation of an essay by the Magazine’s Religion Columnist, Zineb El Rhazoui (who has been erased by much of the discussion about CH). Not sure I agree with all of it, but she brings up some valid points:

“Why the hell is a “white person” who spits on Christianity an anticlerical, but an Arab who spits on Islam is alienated, an alibi, a house Arab, an incoherence that one would prefer not even to name? Why? Do you think that people of my race, and myself, are congenitally sealed off from the ubiquitous ideas of atheism and anticlericalism? “

I really appreciate that idea of Boko Haram using a young girl as a suicide bomber as an act of satire. It’s utterly despicable and evil and cries out for some kind of response (Lord knows what), but, I think aestheticizing the conflict might really help some people understand it. “Boko Haram” means “Western Education Is A Sin.” I have found that amusing ever since I learned it, even if it is the name of a bunch of marauding misogynist butchers.

For me particularly, it helps to underscore the aesthetic shortcomings of Western satire. That cartoon with the sex slaves still isn’t funny because it doesn’t make sense- I get that it’s a response to French welfare policy, but the Boko Haram sex slaves are in Nigeria. But this is what they would be saying if they lived in France? According to conservatives in France? Do French people see all Africans as potential immigrants?

Not only is that not funny to French Nigerians, it seems like it would only be funny to people who thought Boko Haram was in France. And it is poetic that it manages to sum up the two *seemingly* unrelated events dominating the news.

Boko Haram – even in all their despicable violence and murderous mayhem – have always felt to me like satire. Have you seen their ridiculous videos? Add a hip-hop beat to them(Onyx’s “Throw Ya Gunz in the Air’ immediately comes to mind) and tell me if they’re not performing the absurdities of racialized and violent masculinity to its extreme. Over in the West we look at black and brown bodies and reduce them to their most literal meanings (whether we look to rap music or news coverage), which is why we don’t always recognize how they are delivering hyperbolic performances (even those involving murder)for a global audience.

I should also say it is this literalist interpretation of black and brown bodies why it’s so easy for white people (cartoonists or reporters, conservative or liberal)to use us in their images or words to make a point – even if we’re not the subject (in the case of some of Charlie Hebdo cartoons).

Thanks for your comments!

Great essay!

The point about bodies of color being screens for white men to project fantasies and anxieties is an excellent one- and relates really well to my complaints about Joe Sacco’s “On Satire” cartoon,

They essay begins with a demand that greater attention be paid to stories, voices, and perspectives from the margins. By the end, however, it seems to suggest that perhaps the best way to do this is to stop telling those stories — any of those stories — at all.

The Boko Haram atrocities should get more public attention. But then, when they do (via social media), such efforts only further degrade the situation, covering up the real victims and their bodies beneath flippant hashtags, in lieu of “real actions.” (I’m assuming drone strikes and ground forces, no matter how real, would have their own negative effect on African bodies.)

The New Yorker cover, Ms. Hobson agrees, satirizes the xenophobic and racial fever dreams of the American right wing. But in doing so, it makes black bodies the target of humor, while leaving the white objects of that satire free from ridicule. By pairing it with the Hebdo cover, the implication is that the Blitt cover, too, is “punching down,” insulting the marginal, and replicating both stereotypes and racial inequality.

But leaving aside the fact that grotesque white (blue) bodies are forefront in pretty much every other Barry Blitt cover, what exactly are the stereotypes and inequities being replicated here? Upon whom is Blitt punching down? The stereotype of the black man, who is secretly a foreign agent? Are we punching down on real American muslims? Or 1970s era visions of armed nationalists? Perhaps Angela Davis?

None of these seem to be stereotypes that hold much currency these days, although they do fit some slurs directed against the Obamas themselves. But are/were the Obamas hurt by the cover? If this cover, regardless of its intentions, “distorts the truth,” what truth is it distorting? The truth of the Obamas’ dignity? The truth that Barack is not really an American-hating-secret-Muslim? In the end, the real problem seems to be that such a drawing “could easily be appropriated for white supremacist narratives” — namely, that dumb and evil people could make use of satire or ambiguity for their dumb and evil purposes. Again, the best option is to not draw the president at all, just the dumb and evil people.

And finally, we get to the latest Charlie Hebdo cover, which both quotes from previous covers and presents an image that even Ms. Hobson seems to think is heartfelt and honest. But then comes trouble: because it uses a cartoon image of the profit, the “the very peoples and cultures” that are rooted in Islam — and even the authoritarians and terrorists that are the target of the satire — are erased.

But what would be a more acceptable version — a version that remains connected to religion or culture? A more historically accurate drawing? Photos of French Muslims hold “Je Suis” signs? I’m thinking that’s not what she had in mind. The answer, yet again, is don’t draw it at all, no matter how you do it.

I understand the feelings involved in this essay. But there seems to be no way out of the maze. To explain a cartoon is to “rationalize” it obvious moral failings. To defend it is to engage, not in interpretation or clarification, but in “apologia.” And to make an erroneous claim about the public’s reaction to another image is not simply incorrect; it is an object lesson in “unspoken white privilege and power.”

It is telling, for me, that the longest paragraph in the piece is written entirely as a hypothetical, where we cannot even “imagine” a black woman or Muslim liking a certain cartoon, drawing a cartoon, working at the place that publishes them (even as a “token”), or being listened to by the other cartoonists if she did. That is a lot of stuff not to be able to imagine. But it seems to lie at the core of the essay’s solution: try not to talk about it, think about it, imagine it, draw it.

This response is written hyperbolically. Of course Ms. Hobson doesn’t think that everyone should just shut up, forever. But the hyperbole, I hope, has a purpose: to expose some troublesome ideas, in a practical sense, at the core of such measured paragraphs. Sometimes taking an idea and pushing it to its extreme is the best way of doing this. Just ask a satirist.

Janell, have you read Percy Everett’s Erasure? Just thinking about performances of stereotypical black masculinity — the satire of Native Son in that is brutal.

And sort of interesting in a discussion of satire, right? Everett’s satirizing an anti-racist depiction to show the way it’s congruent with racism. But he then ends up (in the novel, and possibly the suggestion is outside it as well) reifying the racist depiction. Satire eats the satirist in that book.

Speaking hyperbolically and without being funny is something plenty of people do- although I think the “tell” for your joke, Peter, is spelling “Prophet” as “profit.” The fact that Charlie Hebdo increased its circulation for this issue by a factor of 100:1 or so would have been an excellent subject for a cartoon.

But the cover had to be an Arab, because to admit the possibility that white supremacism might actually exist is itself a threat to “free speech.” I am reminded of an early ’90s cartoon where someone carrying a sign saying “P.C. fascists won’t let me say anything” is asked, “What did you want to say?” His response: “That was it.”

Also thinking about…what would a caricature of a white man be? How would that work? You could think about R. Crumb’s images of himself maybe…but those really read as a version of a specific kind of failed masculinity, rather than as whiteness per se.

Stereotypes are possible because the marginalized are visible as stereotypes, and the marginal are visible as stereotypes because of the promulgation of stereotypes. The argument about attacking everyone equally seems like it fails in part because there are some people who aren’t marked; you can attack right wing racists, and you can attack black people, and you can attack left-wingers, but caricaturing white people is not possible — or at least takes more work than editorial cartoonists are usually willing to put in.

Also, to Peter — I’d agree that white supremacy is fairly totalizing system. Making good art about racism is hard. That doesn’t mean that you should praise stupid stereotypical images of black and brown people for their nuance and ambiguity.

Edit: Your comment also seems to suggest, Peter, that there’s no possible iconography between drawing the prophet as a racial caricature and drawing the prophet. That can’t be right, surely. I’m hard on editorial cartooning, often, but even I wouldn’t argue that the tradition is so utterly debased that the only possible iconography it can access is racist caricature.

Satire by people of color cam be fantastic. Bamboozled got mentioned in Caro’s thread, and there’s always Putney Swope. Black satire on racism often ends up as pretty hopeless.

In a way, these are sort of the obverse of the film that shares a title with this piece, Sofia Coppola’s crapsterpiece “Lost in Translation.” These redemptive melodramas in which aging white men use the backdrop of some exotic locale to get their groove back show exactly how thin and pathetic our cosmopolitanism truly is.

But the upshot is not that nobody should ever make satire. The upshot is that racist satire is uniquely unfunny and pointless.

“what would a caricature of a white man be? How would that work? You could think about R. Crumb’s images of himself maybe…”

Crumb has a character named Mr. Whiteman…

P.S.- By “hopeless” I mean “depressing.” Which is what satire should be.

Pallas; I’d forgotten that! Sort of telling that it has to be labeled clearly though….

Noah, no I’ve never read Percy Everett’s Erasure. Have to check it out. Admittedly racial satire is tricky. You have to assume your audience is on the same page and have the same experience with race (sometimes that’s just NOT going to happen when you’re on different sides of the racial line). I don’t think the answer is to silence or censor anyone. I disagree with some of the racializing that Charlie Hebdo engages in, but I don’t think that should mean they shouldn’t continue creating their narratives. But they shouldn’t be afraid to be challenged on them either (and no, such challenges should not mean violent retaliation). I personally think a cartoon that parodies the obtuseness of some white men (like CH) on the issue would be just as effective – except would such satirical responses reach a wider audience and hold the same cultural power?

Cabu had a recurring strip in Charlie Hebdo “le beauf”: it was a parody of a typical Frenchman (idiot, racist, mysoginist, …). You can see him on this link (it is the guy in the middle, here with his typical French family):

http://extranet.editis.com/it-yonixweb/IMAGES/CHM/P3/9782862742311.jpg

Hey Bert,

I know you know that hyperbole isn’t just for humor. I’m guessing that was at work in your recent entry too. Turn it up to 11, man.

But speaking of prophet=profit, your words (or, I guess, my words) immediately recalled Art Spiegelman’s version of an anti-Semitic cartoon, drawn in the wake of the Danish drama. Thoughts?

I reproduced Spiegelman’s image here just for the allusion. But I wonder, given the way he draws those Jews, is there a way to avoid calling the comic anything BUT anti-Semitic. I mean, the markers of stereotype are right there! Or take this example, from the same set take this example, from the same set. How can this NOT be both anti-Arab and anti-Jew, with real populations getting disappeared underneath those noses?

But ultimately, it was your use of the word “tell” that was your tell. From that kind of accusation there is no escape. All responses — apologia, explanation, excuse, “damn autocorrect” — lead to the same place: Guilty as Charged.

Most people are thinking this is a zero sum game. It is not.

We hear of marginalised Muslims of the west. Are they really marginalised? What about Muslims in the east – are they marginalised? Much of the dialogue is based on a false reality.

Peter, I just feel like there should be some way to point out that racist imagery is problematic without provoking an instant move to melodrama, and the language of guilt and innocence. Is what’s at stake here really innocence accused? A discussion of structural racism is invalid because individuals aren’t responsible for the structures, and therefore stand unjustly tarred with guilt? I just have trouble seeing that as a helpful road to go down, I guess.

Those Spiegelman cartoons don’t seem especially thoughtful to me. The profit/prophet one in particular — what’s the point of that? “Hey, Jews have been stereotyped too, ha ha”? Great, thanks Art. We’re all humans together, all victims together, so who cares who has the boot on whose throat at the moment?

Spiegelman uses Jewish stereotypes in Maus too — to my mind, rather lazily and clumsily. Again, Percy Everett’s Erasure is a pretty biting criticism of the way that Native Son reifies black stereotypes (he has a bitter quip about how much D.W. Griffith would love Richard Wright’s book.) He also points out that one way for an artist to cash out in a big way is to retail ethnic stereotypes for a mainstream audience in an easily digestible form. Of course, it would be sacrilege to suggest that Maus is doing anything like that. Blasphemy, even.

Hey, Noah. I’m all for the idea that an artistic endeavor can be an absolute an utter failure, and that such failure can include the boring reproduction of racial and racist shorthand. Lots of Charlie stuff fails.

But I posit that, given the essay’s evaluative criteria, there was no way to draw the recent cover’s particular cartoon successfully. Replace the turban (or whatever) with a taqiyah or a keffiyeh, and you still have that nose, as well as a different form of stereotyping. Replace the Squidwardesque schnoz with a pert little circle, and there’s still that beard. Shave the beard and either you still have Mohammed (a problem) or you no longer have anything recognizable as Mohammed at all (a different problem).

Replace the entire thing with this depiction for greater authenticity, slap on a “Je Suis” sign, and … shit. Maybe it’s just best to stay with the unreal — the comic that belongs to the history of Charlie now, and is all but divorced from any real sacred figure.

I don’t know; I feel like some effort to make it not a stereotype couldn’t have hurt.

Robert Stanley Martin has an interesting discussion of the New Yorker cover here.

French muslims receive all the welfare entitlements as any other French citizen. They receive free schooling, health service etc. French law gives them equal opportunities etc.

Yes, Muslims in the U.S. in fact face constant policing and significant marginalization. Arun Kundnani in “The Muslims Are Coming!” says that the proportion of police assigned to Muslims in the U.S. is similar to the surveilance apparatus in the Eastern Block under Communism. His book is eye-opening in many ways.

Muslims are oppressed in other places in the east as well, sure; China and Burma come to mind.

For Crumb’s stereotypes of white people, I’d suggest:

Joe Blow. Dead-eyed, blank-faced, mindless, secretly perverted.

Whiteman, noted above. Buttoned-up and button-down, stressed out, constipated.

Maybe Flakey Foont, Bobo Bolinski, or the Ruff Tuff Creampuffs. But that’s more of a stretch.

Peter, I actually made several efforts (however scattershot) to be funny in my piece about Joe Sacco, and in the comments. I appreciate that Robert Stanley Martin’s piece on the New Yorker cover does something sort of similar, in that it proposes an alternate cover (“they’re both heiresses” is pretty funny). I do think satire does need to be funny to be successful. Not that you have to laugh- you can just feel really uncomfortable and sickened, but you realize that it’s really funny. I re-watched Steve Coogan’s “Knowing Me, Knowing You” BBC series from the 1990s, and the depiction of a spectacularly failing talk show just made me want to go fetal. It’s genius.

Art Spiegelman. on the other hand, is not terribly funny. I appreciate you pulling that out, since it echoes your fortuitous autocorrected phrasing, but it’s a great example of why satire needs to be funny. The subtext of that joke is that it’s not really about Judaism, but Islam, and the ability of Jews to make fun of Muslims, and it is thus using stereotypes of Jews as stand-ins for stereotypes of Muslims. Which is slightly clever, I’ll admit, but the combination of simplistic pun and disingenuousness puts a wet blanket on it for me.

We only know that the Prophet is the Prophet in the CH cover because of lazy shorthand. If they want to be impressive, have an angel dictating the Koran to a pig in women’s underwear.

You are doing a fine job of self-parody, though, in protesting that “all responses” are invalidated. I am engaging with you- you’re the one (as free-speech touters often are (almost wrote “fee speech”)) threatening the nuclear option of ending all dialogue. No, don’t do it!

“Why is it that the black or brown body becomes the vehicle for racial humor when the objects of ridicule – the white people presumably targeted for their racial bigotry – remain invisible in these satirical narratives?”

As a critique of a particular caricature – as opposed to of a general trend in the products of a particular artist, a particular group of artists, or a society in general – this amounts to arguing that every caricature of white people’s beliefs needs a white person in it somewhere, which is obviously silly.

I note in passing the post-modern intellectual’s projecting of his alienation from his own biological physicality onto the artist (“…the black or brown BODY becomes the vehicle…”), and the fact that of course the New Yorker and Charlie Hebdo do caricature white conservatives.

“clever (as racial stereotypes never are)”

Oh come on!

Flatly asserting as axiomatic what we all know isn’t true; essentially insisting that a joke must be moral to be funny; more broadly, that art must be moral in order to be good art. It’s a commonplace to equate political correctness with Victorian moralism, but Janell Hobson seems to be taking that jibe as a GUIDELINE.

Racial stereotypes are stereotypes; they’re clichés by definition. I guess you could think of ways to use them cleverly, but the stereotypes themselves aren’t clever. That’s why they’re stereotypes.

“this amounts to arguing that every caricature of white people’s beliefs needs a white person in it somewhere, which is obviously silly.”

The “obviously” there is doing a lot of work. Racism is pretty ubiquitous, as an ideology and an iconographic and aesthetic tradition. Why is it “obviously” false to suggest that that tradition needs to be fairly radically rethought if you don’t want to be racist?

Finally, I assume everyone knows this, but of course the phrase “political correctness” is always used as a shorthand way to signal that the interlocutor you don’t like has failed to be politically correct. It’s always somebody else committing the thought crime and sliding down that slippery slope…

The Joe Blow stereotype is interesting; it’s not really a caricature at all. There’s nothing really exaggerated about it. Whiteness is normality.

Again, Whiteman has to be labeled as whiteman so you know that’s what it’s stereotyping.

Another of Spiegelman’s “anti-Semitic” cartoons was one of the few things he’s done that made me laugh, though. I can’t find it online, but it was something along the lines of a Jewish guy at a restaurant telling the waiter, “Oh, I suppose I’ll just have the lamb, along with the blood of a Palestinian child.”

Have you heard/seen Spiegelman’s appearance on Democracy Now! to talk about Charlie Hebdo? It’s pretty interesting toward the end; he gets into a bit of a shouting match with Tariq Ramadan, a professor of Islamic studies at Oxford.

http://www.democracynow.org/2015/1/8/comics_legend_art_spiegelman_scholar_tariq

Bert, please go back and insert a winking face after that last paragraph of mine. :) I didn’t really mean that you were shutting me down. I just thought that the vocabulary of “tell” — where your hidden motives or real holdings are revealed, without your consent on knowledge — was, y’know… I do love chatting here, and I appreciate the engagement. Peter

It’s interesting because for years, everyone else in the world (including Australia, where I live) has been saying ‘the Americans don’t understand satire’. Obviously, there have always been many Americans who are brilliant at it, but the perception has been that mainstream American culture is incapable (or relatively less capable) of laughing at itself. Now there is a world event which depends on Americans understanding satire. It’s been interesting to watch everyone, cartoonists, journalists, news reporters, trying to wrangle with it. Even we cynical, grumpy Australians have been asking, ‘but do WE even understand satire? Really?’

I was living in the outback for a few years, where the overt racism takes the skin off your teeth and makes you sweat, and that’s from behind a sheltering layer of white skin, and periodically I would return to my home town and spend a night or two with a dear friend who is a psychologist, and we would stay up late trying to make sense of it all. ‘They say this,’ I would say. ‘They say that.’ My friend’s husband would walk through and say, ‘it’s terrible when she comes to stay, spouting all this racist crap.’ And my friend would say, ‘no, she hates it. She doesn’t understand it. She’s harmed by it. She’s trying to make sense of it.’ But I think he was never convinced.

Fundamentally we are all sides of the same coin. Harm done to one side of the coin damages the value of the entire coin. I am the marginalised Aboriginal people in the outback, and I am also the threatened whites who live alongside them. I am that frightened ten-year old walking into a market, willing people with my eyes to run away. Or I am that ten year old, believing that I am doing good, willing them to stay in place. I cannot now know what she was thinking. We humans breathe the same air and drink the same water. How do we discuss this devaluing that we do habitually and reflexively? With punching-down satire? With guns?

In the outback, I saw many well-meaning people trying to defuse ranting racists. Nothing worked. Only one woman even came close. A big, fat, rather scary-looking lesbian woman. She sat at the bar and looked at those guys, looked at me freaking out, assessed the situation for a moment, slumped down a little, looked the guys in the eye and said, ‘you’re breaking my heart, mate. You’re breaking my heart’.

Jack,

The third anti-Semitic Spiegelman cartoon, from his New Yorker triad, I cannot find online. The Jewish man is saying to the waiter, waving her away: “No more Palestinian blood for me, thanks. Its bad for my cholesterol.”

But here’s a fourth, reprinted in Harper’s — the issue about the Danish cartoons.

I like that one better…even the art is better, I think.

Churches burnt in Africa black Christians put to the flame as a wave of anti Charlie Hebdo goes around the Muslim world:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-30853305

@ Noah

“I guess you could think of ways to use them [racial stereotypes] cleverly…”

This just acknowledges that it is the way an artist uses her materials, rather than the materials per se, that is interesting in art.

And Hobson is saying exactly that you CAN’T use racial stereotypes cleverly.

“Racism is pretty ubiquitous, as an ideology and an iconographic and aesthetic tradition. Why is it “obviously” false to suggest that that tradition needs to be fairly radically rethought if you don’t want to be racist?”

If our conception of racism suggests that putting a white person somewhere prominent in either of the cartoons, perhaps with a thought bubble reading “This is the way I see the world,” would make a significant positive difference, then maybe our conception of racism needs to be radically rethought.

I debated using the phrase “political correctness,” because nobody has owned it in a long time (like “liberal” in the ’90s and early ’00s, though that one has since made a comeback), but wasn’t sufficiently motivated to come up with a less loaded replacement. (Political sensitivity? Racial sensitivity? Probably should have gone with the last one.) But your conclusion that I meant it in a necessarily pejorative sense, which I didn’t, looks like an attempt to find an excuse for dismissing the rest of what I wrote.

@ Linke

Thank you for posting that link!

@ Noah

“Also thinking about…what would a caricature of a white man be?”

The answer has to be: What kind of white man? Obviously you can think of plenty of examples of caricatures of rich white men (Eustace Tilley), poor white men (Al Capp), nationally specific white men, etc (and women, of course).

The predictable rejoinder here is: “If it’s of a specific class/etc of white person, it’s not merely a caricature of white people.” But then, it would be hard to find a caricature of a non-white person that isn’t also somehow specific in terms of class, occupation, or something else in addition to race.

Requiring that a cartoon make sense is not politically correct. It’s aesthetically correct. A cartoon that uses racist images needs to justify itself, or, regardless of the intentions of the artist, it’s a racist cartoon. If I am just supposed to assume that every racist image drawn by a white person is intended ironically, I just refuse. If that seems somehow moralistic on my part, I am happy to discuss it.

I like confabbing with you too Peter. All winky emoticons retroactively presumed.

I also like that Holocaust-denial cartoon. It completely makes sense, and it’s funnier than the “profit” one not just because it is choosing a less questionable target, but because it uses absurdity to call out something foolish in a simple and devastating way. No stereotypes required!

“But then, it would be hard to find a caricature of a non-white person that isn’t also somehow specific in terms of class, occupation, or something else in addition to race.”

I don’t think that’s really true. Blackface caricatures are pretty universal; it’s an iconography that works for any black person, pretty much. That’s the point of the caricature really. It reduces people to blackness, whoever they are. It’s very hard to think of anything that does that for whiteness. As you say, wealth, poverty, or what have you, become the thing caricatured. Whiteness is uncaricaturizable; it’s the default. (I have a piece on this here.)

” debated using the phrase “political correctness,” because nobody has owned it in a long time (like “liberal” in the ’90s and early ’00s, though that one has since made a comeback), but wasn’t sufficiently motivated to come up with a less loaded replacement.”

I think Charlie Hebdo was often lazy in that way too.

If “politically correct” isn’t meant pejoratively, then you need to find another term, yes. PC is a slur, and generally meant to be so.

I just noticed that Democracy Now has a second part of its Spiegelman interview up as a web exclusive. In it, he defends the New Yorker fist-bump cartoon (“It helped get Obama elected, damn it,”) and discusses Art Young, also mentioned in Noah’s original anti-Spiegelman piece.

http://www.democracynow.org/blog/2015/1/8/cartoonists_lives_matter_art_spiegelman_responds

Adding to the answers to question of what a white stereotype would look like, I’d suggest having a look at some Dave Chappelle’s “white-face” bits from the Chappelle Show. He often played that character against the stereotype of a hyper-masculine black man, and the result was what I’d call really smart satire. However, it’s worth noting that Chappelle turned his back on the show because he worried that certain members of his audience were laughing for the wrong reasons, and that he might be doing more harm than good.

Returning to the article, we’d all do well to remember Hobson’s point that cartoonists make choices about how to do satire, and what contextual (read socio-cultural) beats to hit. Too often, people write about context as monolithic, and the symbolic resources of cartoonists as limited. I’d suggest that there’s a lot of room for creativity, and that it’s more than possible to make fun of a bully without throwing his victims under the bus.

“Blackface caricatures are pretty universal; it’s an iconography that works for any black person, pretty much.”

Well, no, it doesn’t “work” very well for Ethiopians, just as an English caricature of a French doesn’t work very well for a Swede, and a French caricature of an English doesn’t work very well for a Greek.

And again, blackface usually isn’t merely blackface, but a blackface version of a southern farm worker (or slave depending on time period), or urban nouveau riche, and so on.

I have read that piece.

‘If “politically correct” isn’t meant pejoratively, then you need to find another term, yes. PC is a slur’

No it isn’t, and calling it that looks like you’re claiming parity with a black person who’s been called you-know-what, etc.

@ Bert

“A cartoon that uses racist images needs to justify itself, or, regardless of the intentions of the artist, it’s a racist cartoon. If I am just supposed to assume that every racist image drawn by a white person is intended ironically, I just refuse.”

Is the irony in the Charie Hebdo cartoon or the New Yorker cover reproduced above unclear to you? The question is rhetorical.

@ Noah (continued)

It is true is that the most grotesque caricatures drawn by westerners of non-whites – maybe particularly of black people and eastern Asians – are bestial in a way that our caricatures of white people hardly ever are. (Of course, if a western cartoonist wanted to use the most grotesque old types while treating whites equally cruelly – which might be interesting – he would have a ready model in eastern Asian caricatures of white people.) But the Charlie Hebdo cartoons are far from the most grotesque, and, I submit, not different in kind from how they draw white people.

My answer is not rhetorical, though. I never saw that New Yorker cover, and I get it, but the caricatures of Barack and Michelle frankly suck. Not that they’re not pretty drawings- the artist is trained- but they don’t look like Barack and Michelle. Interestingly enough, they seem to have been deliberately skin-bleached, for some reason. Otherwise, no, I do get the context… because it’s on a New Yorker cover. On its own, it’s pretty easy to transplant it into the National Review. Which does not make it edgier, it makes it vague and thus unsuccessful.

The Charlie Hebdo cover- no. I didn’t know what CH was before the shooting, I am fairly caught up now, but I am not totally sold that the magazine doesn’t flirt with Christopher-Hitchens-esque liberal-militarist tendencies. So no, the context is not clear, rhetorically or otherwise.

Oh, please. All slurs aren’t equal. PC is meant pejoratively. Either you’re significantly dumber than I think you are, or you’re arguing in bad faith, or the need to justify a bad decision has led you to double down on an untenable position. I presume it’s the last one.

You can read Wikipedia if you want. It classifies them it as “generally pejorative.” The International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences says it’s a “term of derision.”

http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Political_correctness.aspx

I guess if you can find me any counter-examples, go ahead. I’ve always heard it used as a sneer. That’s how you used it as well.

I think you misunderstood me. I didn’t mean that any black person would understand blackface iconography; I mean that it could be used to represent any black person. And I think that’s correct; it’s used equally to represent Africans (like the Jungle imp), or rural people, or city people. It treats all black people the same.

I think Bert’s point about the New Yorker cover is that the irony seems entirely dependent on the idea that the person creating the caricature is not racist. There isn’t really anything else in the image that would tip you off; there’s no thinking through the stereotypes. They’re just reproduced, as if that’s sufficient. At some point, when you do that, you’re just having fun drawing racial stereotypes. Which is kind of racist.

The Charlie Hebdo cartoons don’t actually seem ironic. They draw caricatures of Muslims to make fun of Muslims. You’re supposed to understand it as tweaking radical Islamists, and the cartoonists are again, supposed to be understood as not racist, so it’s okay for them to draw Muslim caricatures to demean certain Muslims, supposedly. As an anti-racist effort, it doesn’t seem very effective. (The Boko Haram one is closer to the New Yorker cover, though, again, retailing racist stereotypes in the understanding that it’s okay because you’re not racist doesn’t seem either aesthetically or ethically intelligent, to me.)

@ Bert

“The Charlie Hebdo cover- no. I didn’t know what CH was before the shooting…”

Well, if the joke was dependant on knowing Charlie Hebdo’s politics – which, granted, the New Yorker cover is – then the question isn’t whether you knew, but whether the French (which I’m assuming you’re not) were likely to know.

But the joke isn’t dependant on that. No conservative would ever write “Boko Haram’s sex slaves are angry” over that picture and speech bubble.

Sorry- I was talking about the Prophet cover this week (duh). As for the sex slaves cover, I talked about that earlier- it seems to not make sense even in the French context, since (as I perceptively noted) Boko Haram is not in France. If there’s a French assumption that all Nigerian refugees are going to end up in France receiving welfare, perhaps that makes sense, but it’s super racist and paranoid, and only marginally more clever than the nonsensical non-racist version.

“Oh, please. All slurs aren’t equal.”

Yes, exactly, and nobody was ever psychologically devastated by being called “PC,” so equating my use of the term with the “carelessness” of which you accuse Charlie Hebdo (leaving aside the question of the validity of that accusation) is a cheap rhetorical trick.

“They draw caricatures of Muslims to make fun of Muslims. You’re supposed to understand it as tweaking radical Islamists, and the cartoonists are again, supposed to be understood as not racist, so it’s okay for them to draw Muslim caricatures to demean certain Muslims, supposedly.”

Except, as Bert Saunders pointed out in his article here the other day, you’re not supposed to understand it merely as tweaking radical Islamists, but also as tweaking the prohibition on ethnic humor.

Insofar as the grotesquery in the caricatures has a specifically ethnic element at all, which it does in some but not all of the Charlie Hebdo cartoons that you can see on Google Images right now (not, for example, in the new Mohammed cartoon reproduced at the end of this article).

But this is all somewhat beside the point of what Hobson wrote about that particular Boko Haram cartoon.

“If there’s a French assumption that all Nigerian refugees are going to end up in France receiving welfare, perhaps that makes sense, but it’s super racist and paranoid, and only marginally more clever than the nonsensical non-racist version.”

Alright, I thought everybody had gotten the memo by now, but evidently not. The point is to make fun of the French conservatives’ attacking Muslim immigrants as welfare moochers, by pointing out that the French conservatives are essentially saying that people such as the refugee former sex slaves of Boko Haram came to France just to reap the benefits of the country’s welfare system.

“you’re not supposed to understand it merely as tweaking radical Islamists, but also as tweaking the prohibition on ethnic humor.”

Right; so they’re making fun of the Islamists with racist humor, and making fun of the idea that they shouldn’t be allowed to be racist. I am unimpressed.

I didn’t intend to say that the use of PC was as harmful as the Charlie Hebdo cartoons; it isn’t of course. I was just saying people can sometimes be offensive unintentionally out of laziness or an unwillingness to spend the time that it takes to not rely on lazy stereotypes or language.

“Right; so they’re making fun of the Islamists with racist humor, and making fun of the idea that they shouldn’t be allowed to be racist. I am unimpressed.”

Well that’s not surprising. You’re essentially the target.

Or maybe “essentially” is the wrong word. Their target is of course primarily a FRENCH conception of anti-racism. Better to say you are, in this case, in agreement with their target on a significant point.

In 2013, Charb tried to delineate the difference between satire and hate-speech or racist speech, between Charlie Hebdo and the right-wing publication Minute. I think the key aspect, for him, is in boldface:

“…to hide behind a satirical newspaper known for its anti-racist and anti-fascist positions in order to justify racist and hate speech is both grotesque and frightening.

“It is grotesque because the racial slur has nothing to do with a critique of some aspects of a particular religion or a particular school of thought.

“It is scary because the purpose of Minute [in hiding behind satire and CH] is clearly to trivialize the racist insult.”

http://www.humanite.fr/charlie-hebdo/minute-n-est-pas-charlie-hebdo-le-racisme-n-est-pa-55313

No Graham, I got that memo, but the context is still vague. Either the joke is that Boko Haram’s sex slaves (who are in Nigeria) are getting welfare from the French government, which makes no sense.

Or the right-wing stereotype of pregnant black Muslim welfare queens just happens to resemble the Boko Haram sex slaves, who are also pregnant black Muslim women. So the joke is based on the idea that all black Muslim women are the same.

But the gag is then that this indiscriminate lumping-together of suffering vulnerable people is *what the racists are doing.* But, like the New Yorker cover, it works perfectly well if you plop it into a specifically right-wing context.

In fact, it works better, because you don’t have to figure out whose point of view is being adopted and what the frame is. That is crap satire.

Speaking of blackface, there was a similarly sloppy gesture made in Chicago a bit over a year ago by an artist who thought it would be hilarious to promote a fictional blackface concert at an area high school– I had to deal personally with this jag off, as he was writing to me “in character.” Here’s a link about it: http://www.chicagoreader.com/Bleader/archives/2013/12/17/a-tale-of-two-minstrel-shows

“Or the right-wing stereotype of pregnant black Muslim welfare queens just happens to resemble the Boko Haram sex slaves, who are also pregnant black Muslim women. So the joke is based on the idea that all black Muslim women are the same.”

Is is incoherent.

The joke is not complicated. A right wing fever dream is depicted and mocked by the caption.

“But, like the New Yorker cover, it works perfectly well if you plop it into a specifically right-wing context.”

No it doesn’t. A conservative magazine might have run the New Yorker cover. No conservative would ever pair that image and speech bubble with that caption.

@ Peter Sattler

I would say that one purpose of some of the Carlie Hebdo cartoons is certainly to “trivialize the racial insult,” and I wouldn’t say that’s negated simply because it’s accompanied by critique of religion or ideology.

I would say a significant difference is whether the cartoon is attacking anti-racist taboos as part of an attack on all taboos in general, or tearing down those taboos merely in order to better uphold others. For a powerful example of the latter in contemporary America, see that maker of thinly veiled panegyrics to white people, the army, big business, Judeo-Christian religion, and the moderately patriarchal nuclear family, Trey Parker. (I haven’t seen anything by Minute.)

I feel like we’re pretty much going round in circles at this point, and rather losing the thread of Janell’s post as well. So I’m going to bow out, I think.

Just to say- if you think there isn’t a group of 50,000 racist Americans who would respond positively to a blatantly racist attack on welfare queens, I sincerely beg to differ.

To my eye, the big difference between the CH cover and the New Yorker cover is that the latter functions according to what Kenneth Burke called “perspective by incongruity.” That is, Blitt takes two things that one normally sees as opposed (the scene of the “White” House and popular images of “Black” Power), and then puts them in proximity to illustrate the absurdity of a particular belief system. Basically, juxtaposition, and not the stereotype, carries the burden of the comedy.

Of course, one could criticize the cartoon on the grounds that it by portraying the Obamas as militants the cover is offensive at first glance, or that it is lost on folks who actually believe that the Obamas are militants and don’t recognize the stereotype as absurd. But it would be harder to argue that someone who didn’t already have those beliefs and who looked at the cover for more than 10 seconds would be similarly confused.

The CH cover, on the other hand, adopts the perspective of the group of which it is critical. Moreover, it does this at the expense of an already marginalized group that has been marginalized not only by politicians, but also (if only in part) by a history of Franco-Belgian cartoon stereotypes.

This is an interesting quote from the Spiegelman/Tariq Ramadan discussion:

“TARIQ RAMADAN: We are talking here about a policy that was said by Charlie Hebdoover the last years that is mainly targeting the Muslims. My point here is, once again, I’m not—

ART SPIEGELMAN: But why?

TARIQ RAMADAN: I’m not—

ART SPIEGELMAN: Why were they targeting Muslims? Do you think it’s—

TARIQ RAMADAN: I’m not—you know why? You know what? You know why? It’s mainly a question of money. They went bankrupt, and you know this. They went bankrupt over the last two years. And what they did with this controversy is that Islam today and to target Muslims is making money. It has nothing to do with courage. It has to do with making money and targeting the marginalized people in the society.

The point for me now is just to come with you, as somebody who is involved in this, and to come with the principles that you are making now, and to come and to say, look, now, in the United States of America as well as in the West, everywhere, we should be able to target the people the same way and then to find a way to talk to one another in a responsible way, not by throwing on each other our rights, but coming together with our duties, our responsibilities to live together.

I think that what you are saying now could be dangerous if you are not coming to the facts, but just with the impression that their past is similar to the present. Charlie Hebdo is not the satirical magazine of the past. It is now ideologically oriented. And Philippe Val, who was a leftist in the past, now is supporting all the theses of the far-right party, very close to the Front National. So, don’t come with something which is politically completely not accurate.”

Tariq Ramadan is such a lying shit.

Ah well; I’m sure he wouldn’t agree with you either, Alex.

Edit: I don’t think it’s very helpful to say that folks don’t understand the context, and then accuse people who do understand the context, but disagree with you, of being liars or frauds. Obviously, CH’s legacy is somewhat controversial. It’s not just an issue of context; people actually disagree about what the magazine was doing, and what that meant in terms of the Muslim community in France. That seems like it’s pretty important to acknowledge, to me.

But he’s lying on points of fact, not of interpretation. For instance, Val is definitely not on the far right at all. And the assertion that CH has for reasons of greed only recently targeted Islamism is as odious a misstatement as possible, especially ignoble in light of the murders. They have always mocked Islam as they have mocked other religions, from the start (1971).