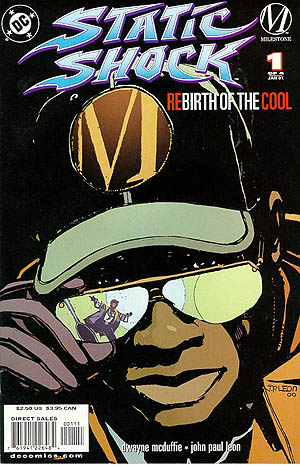

Static is the best known creation of the Milestone Comics label. Judging from the first collected volume, the rest of the line must be unmemorable indeed.

It doesn’t give me any joy to say that. Milestone’s efforts to create greater diversity in superhero comics were admirable and courageous, and I would like to be able to praise the results. But writers Dwayne McDuffie and Robert L. Washington III offer little in the way of innovation, or even interest. Static seems borrowed wholesale from Spider-Man — and not even from Lee/Ditko Spider-Man, but from the less interesting, less urgent, undifferentiated later rehashes. Static is a 15 year old trash-talking superhero. And…that’s really all there is to him. He experiences some minor relationship angst; flirts with some criminal acivity — but everything is resolved with little fuss or interest. Then the second bit of the first volume is given over to a largely incomprehensible and tedious crossover with a bunch of unmemorable other heroes. The goal is obviously to recreate the sense of a world of super-heroes you get in DC and Marvel — and I did get to feel just how utterly unapproachable those worlds must be to anyone coming to them cold without decades of background. I didn’t know who any of these people were, and there was no effort to make me care. The whole thing was almost impossibly pointless; random characters kept leaping up with no introduction to say something portentous before getting blasted. The whole exercise was dreary, joyless, and confused; not notably worse than the DC and Marvel competition of the day, but not any better either.

There’s a parallel with “Sleepy Hollow” perhaps, a current paranormal/crime television show notable for having a (relatively) diverse cast — and for not much else in terms of quality. I wish Sleepy Hollow was better, just like I wish Static Shock was better, because I appreciate their efforts to be more diverse and less racist than the competition, and I would like to be able to embrace them wholeheartedly.

But though I don’t really want to consume either Sleep Hollow or Static Shock, their badness is in its own way a kind of worthy breakthrough. Diversity shouldn’t have to mean greatness; most genre product is mediocre, and so, ideally, in a more diverse, less racist world, you’d have a lot more diverse mediocre genre product. White superheroes shouldn’t be the only ones who get to be poorly written and indifferently drawn; white actors shouldn’t be the only ones who get jobs in poorly conceived sit-com/adventure dreck. If we’re going to have mediocre entertainment, it should, at the least, be less racist mediocre entertainment. By the same token, I hope the new Spider-Man in the Marvel cinema franchise is played by a black actor. Someone is going to get to star in a massively overhyped bone-dumb nostalgia vehicle with explosions and moderately funny gags. Why should it always be a white guy?

If you read the recently released trade paperback (recently being like four or five years ago), then those initial issues and the later brief two-parter done when the cartoon was first produced do not really represent the whole of the Static series. The initial stories by McDuffie just laid the groundwork, and don’t speak for the quality that the remainder of the series’ 45 issue run had.

I would say that in terms of writing quality, Icon is much better. I like Static as a character more, but from a storytelling aspect Icon remains to this day to be very good. That was more of a commentary on superheroes and race, so that may be closer to your interests.

Yeah…it would have to get a lot better before it would get past mediocre. I can’t say I’m much tempted to try reading more…

I thought Icon was much better (at least at first). Have you not read that book? I feel like someone on this blog wrote a thing about it.

Hardware is awful. Sort of like Iron-man, but much, much worse.

I haven’t read Icon; I think it’s been mentioned, but I don’t know that anyone here has actually written about it….

Too bad, I remember like the cartoon a lot :( Like maybe it wouldn’t hold-up if I rewatched it but at the time it was fun wish-fulfillment that was more relateable than Spiderman + the voice acting was good

Too bad, I remember liking the cartoon a lot :( Maybe it wouldn’t hold-up if I rewatched it but at the time it was fun wish-fulfillment + the voice acting was good

I always think of McDuffie as having worked in the same school as Kurt Busiek/Mark Waid/Peter David in that his real talent was digging into the lore to make you care about the characters, not the reverse as so many other superhero writers do. The fact that he had a rocky first few issues in a world that hadn’t been super built up to that point doesn’t surprise me in that light.

Icon holds up, I think, and so does Xombi.

“Someone is going to get to star in a massively overhyped bone-dumb nostalgia vehicle with explosions and moderately funny gags. Why should it always be a white guy?” – Noah Berlatsky

I didn’t read Milestone Comics when I was young; recently I’ve reviewed the first two arcs of Icon and found a standard-issue 90’s comic with extra social commentary draped around the narrative every few issues like an ill-fitting suit. With those opening issues, it appears McDuffie was constrained by the superhero formula, and delivered a character whose very approach to social justice and Black politics should not allow for the solution Rocket wrings from spandex. My point? Maybe the early Milestone material was bad because the superhero concept does not fit people of color very well.

I can’t think of a superhero comic character who embodies a recognizably authentic Black narrative. Even pioneers like McDuffie too often based their characters around preexisting superhero comic tropes: Icon as the space-alien who can do anything save the wrong thing, Static as the teenager with a gift for gab as you mention above. Race delivered in comics via palette swap does nothing to challenge or innovate the superhero concept, so even the conscious attempt to add race and gender consciousness or class concerns to superheroes results in muddled, struggling comic stories.

Should it always be a White guy who gets to star in the summer blockbuster comic movie? Perhaps not. But if the bone-dumb nostalgia vehicle does not elevate itself past explosions and moderately-funny gags after casting a Black Spider-Man or Black Johnny Storm, then one has to wonder what we gain as consumers from all that visible melanin. Apparently its not enough to give us a good movie, given this logic.

Well, we’re not going to get good movies, so that’s a given to start with.

Diversity is important because it’s hard for people (black and white) to imagine black heroes if black heroes are never shown in the media. If black people are never viewed as protagonists, or as worthy of empathy, that plays into stereotypes and violence (there’s a lot of research on how police violence against black people is tied to lack of empathy.)

I agree that often there’s little innovation in comics. However, I’d dispute the idea that comics with black protagonists are somehow worse or more muddled than those with white protagonists. Superhero comics in general are crap. If they’re going to be crap, though, I would vote for making them less racist crap.

Noah, if people view diversity as important in comics, that’s fine. But we can achieve diversity in comics without retelling Spider-Man’s origin for a third time in a generation on screen with a Black Peter Parker as the only innovation. It’s reasonable to conclude from that proposal that superhero narratives can be used to remind people of Black heroism (though history and modern news offer uncountable examples) so long as the old White male power fantasies superhero narratives provide are never altered. I oppose that. Racebending established characters only appears sensible because new characters don’t often sell weekly issues and movie tickets.

By many accounts, the early Milestone material wasn’t very good. I believe that happened for the same reason that the Secret Identities anthologies from a few years back filled with stories about Asian American superheroes failed to excite: superheroes were never designed with people of color in mind. Or put another way: if Alan Moore is right, and stuff like the Avengers movie raises concern because people are “delighting in concepts and characters meant to entertain the 12-year-old boys of the 1950s”, then why should we forget that those concepts and characters existed with specific racial content in mind? To appeal to 1950’s twelve year olds, the characters were designed to inhabit a monoracial world.

There’s no reason that today’s comics should hit those same notes, but writing new material with new characters of color appears the only ethical option in pursuit of comic diversity. This means that an endless parade of comic book movies with the same old stories from the same Silver Age source material — all White male power fantasies for White male adolescents — cannot hope to offer meaningful diversity though simple casting choices.

Superhero comics are in general crap; we agree there. But there’s no more reason to watch a Spider-Man film with Childish Gambino or Steven Yuen as Peter Parker than there is to watch it when Andrew Garfield was cast, nor is there any reason to believe that casting an actor of color automatically makes the resulting product less racist crap. Comics with protagonists of color are not more muddled than comics starring White protagonists, but they do tend to shoehorn people of color into genre conventions that one doesn’t often find among individuals from the hero’s community.

Or maybe I’m sensitive to this because I don’t often find many brothers walking down Flatbush Avenue wearing gaudy skintight spandex.

I think casting more diverse people does in fact make the resulting product less racist. Not necessarily better in other ways, and not necessarily unracist, but yes, acknowledging the existence of poc as heroes and audience is a move towards less racism. Will it bring about the utopia? No — but the civil war didn’t do that either, you know?

I’ve written quite a bit about the innate racist assumptions of the superhero genre…here for example (though I’m not overly fond of the title.)

http://www.esquire.com/entertainment/movies/a23799/black-superheroes/

Thanks for sharing your Esquire piece. I don’t think our positions are that far apart, but it’s clear I lack your optimism in this. The argument that allowing for racial diversity in casting makes those products less racist (presumably than films that display monoracial movie casting) requires the assumption that racial visibility alone is a public good. I disagree. I’ve no use for pop culture that remembers I exist, but can only use me as scenery for narratives that examine Whiteness, or promote White heroism. I’ve even less use for pop culture that remembers I exist, but can only articulate my life and experiences through simplified, prefab narrative structures designed to lull people outside my community with cheap laughs so they may respect my humanity for thirty minutes on Tuesday nights. (Fresh Off the Boat is usually justified with the same visibility arguments you’ve made, and it’s another bad attempt at diversity hobbled by its conformity to mainstream approved narrative and humor development.)

Anthony Mackie’s Falcon may have brought smiles to some comic fans in Captain America: The Winter Soldier, but I only saw a brother position himself three and one quarter steps behind America’s most beloved steroid abuser. It’s not clear how the display of a subservient Black man on screen is less racist than simply leaving the Falcon out of the narrative entirely. Again, no one’s asking for utopia — the request here involves the development and promotion of comic narratives featuring people of color that offer some genuine authenticity, some actual reflection on and understanding of what it means to be a person of color in America.

I do not believe the superhero concept can handle such innovation. I wrote about it here: Jackie Robinson and the Mythic Black Superhero – https://snoopyjenkins.wordpress.com/2014/03/05/jackie-robinson-and-the-mythic-black-superhero/

But I really appreciated the point in the Esquire piece where you question how reasonably a Black superhero can pursue vigilante justice and maintain her Blackness, broadly defined. For me, the very fact of that tension suggests that the superhero concept itself does not allow for race and gender diversity the way some of its fans would prefer. I wrote about that here: Superman is a White Boy – https://snoopyjenkins.wordpress.com/2014/03/27/superman-is-a-white-boy/

Thanks for sharing your link, and for an amazing site. It’s really good to know that there are places where people take comics seriously enough for real criticism.

Yeah; obviously representation alone isn’t enough if it’s racist representation. I don’t really think that’s the case with Static; that is, the comic doesn’t do anything especially interesting with race, but it doesn’t really use racial stereotypes I don’t think either — and it’s at least a case where the black hero is really the hero; it’s Static’s story, he’s not playing second fiddel to someone else.

I will check out your site…and I’d love to have you write for us here…maybe I’ll email…

I’d be curious to hear what you think about Ms. Marvel, which I think does challenge the usual racial script of superhero comics in interesting ways…have you read that?

I read the first arc of Ms. Marvel. The comic succeeds as a statement of gender empowerment in comics, but I’m still unsure about it on race. Kamala Khan presents your typical second generation immigrant angst, but since the comic includes a fully functioning family structure, Kamala does not exist as the only representation of non-European difference in the comic. Add in the friends and the religious settings, and Kamala offers one element of a community presentation of non-European difference in the narrative, and to my mind, not even the primary one.

In no small way, this deserves credit. Kamala’s free to be ‘just a girl’ in this comic, and many find her relatable and enjoyable because of that. She’s not defined by her race. If anything, Ms. Marvel (in the first arc, anyway) was an updated, gender reversed Peter Parker, replete with a mean girl Flash Thompson, and the story includes all the teenage awkwardness one can expect from that foundation. That’s the jumping on point for all the expected repressive immigrant parenting and WASP entitlement and non-Christian religious practice that Wilson stuffed into the narrative. So the innovation here is the method by which an existing superhero narrative structure was co-opted to include a multi-dimensional, if stereotypical minority perspective.

Yet for me, Ms. Marvel is first and foremost a feminist book, where a female protagonist defies patriarchy. Whether sneaking out after curfew to attend a high school party, or fighting punks in a convenience store, Kamala cannot be restrained by men. It’s a beautiful book for teenage girls, but I’d need to read more to decide if its race politics are worth the effort.

And thanks for your interest in my writing! Yeah, hit me up on email; I’d love to talk more.

That’s interesting…I think there’s a fair bit in Ms. Marvel in terms of assimilation; superheroes are figured as “American” but that american is then defined to include Ms. Marvel. There’s some nice stuff with her starting out as white in her superhero identity, and then switching to look just like herself, sort of accepting that people who look like her can be superheroes as well.

It’s definitely not revolutionary in terms of its politics, but I think it’s smart about race and how that can fit into the superhero narrative…

Noah, Jeffrey Brown’s book on Milestone and race is pretty good and reveals some ways in which Static might be more worthwhile that you suggest. J. Lamb/Snoopy Jenkins…that’s a hell of an essay on Superman as white boy. I’m kind of working on an essay with some similarities…not sure I should bother now.

Eric, thanks for the support! Definately finish your Superman essay; I’m interested in reading it.

Though thinking again about static…the first issues do that thing where the one guy who talks about racial inequities is the supervillain,and Static has to learn to resist his seductive race-baiting logic. So that would be a point for your argument, I think.

I’ve been working on an article about the successes failures of non-white comic heroes for months now. It’s incredibly hard to nail thoughts down to a digestible length, but there are characters out there who do go beyond pallet-swiped white character characterization in mainstream comics. The Cassandra Cain Batgirl for example is a character who rarely conformed to the ideal of a typical costume hero at the best of times, which I feel is a reason why she’s been shelved for years now because mainstream writers want a more typical and boring female crimefighter in the Steph Brown and Babs Gordon Batgirls.

But for books like All-New Captain America, in this current season of racial unrest, its worthlessness in promoting the first African American comic superhero to the title of “Cap. America” with how it does nothing but beat the character up and not even briefly mention the social ramifications of this is just relentlessly depressing.

This is a classic damned if you do damned if you don’t scenario. Create a black hero in the Spider-man mold and you’ll be accused of doing a “pallet-swipe”

But address racism in a book like Icon and you get accused of “extra social commentary draped around the narrative every few issues ” as J. Lamb wrote.

Well…I think it’s more like, damned if you don’t do it well. Which seems reasonable.

I haven’t read Icon…and I don’t think J. Lamb mentions that? Like I said, I think Ms. Marvel is thoughtful in its handling of race. Captain America Truth is too…though it sort of falls apart at the end.

Icon at the very least tackles race head on in its premise. The character of Icon becomes a superhero at the urging of his eventual sidekick Raquel who sees the potential for him to serve as a black Superman and lift up the black community from the depths of the mid-90s.

I don’t think its really a question of “doing it well”. The issue is to some extent the creators of these books were trying to create an adolescent power fantasy for African Americans kids, and it seems to me there’s this projection from critics as to whether the characters represent all black people, or their lives are sufficiently dis-empowered to show problems facing real black people, or something like that. When that wasn’t necessarily ever the goal.

I think that’s a little simplistic, Pallas. I’m sure it wasn’t the goal of most mainstream comics to deliberately exclude black people from their adolescent power fantasies. And yet, somehow, you still get a situation where black people are excluded.

J. Lamb’s point, I think, is that diversity in itself isn’t necessarily good enough. Think of it this way. Is Little Nemo not racist because one of the main characters is the Jungle Imp? No, because the Jungle Imp is a racist caricature. How diversity is done matters a lot. You can argue about how well a given portrayal succeeds or doesn’t. But the suggestion that a work is somehow beyond criticism because it’s well-intentioned…I don’t think that’s a very convincing argument.

Beyond that…J. Lamb is making the argument that whiteness is central to the superhero concept. I think you can go back and forth on that…but it’s undeniable that the superhero genre is obsessed with criminal justice, and that criminal justice in the U.S. is almost impossible to separate from racism. Do black cops reduce racism? I could see an argument either way.

“J. Lamb is making the argument that whiteness is central to the superhero concept”

Right… and considering the black folks at Milestone clearly saw something in white hero books, and wanted to make some hero books of their own, I see this argument as kind of odd.

“J. Lamb’s point, I think, is that diversity in itself isn’t necessarily good enough.”

There is no actual standard of “good” in this contexts that you can refer to when speaking of diversity in superhero comic books. It’s more useful to talk about the relationship between the authors and the readers.

Again, you need to think about the fact that the intended reader was likely teenagers, probably not even people who had read the “good” Spider-man by Lee/ Ditko. Teenagers not necessarily looking for anything more complicated than what Stan lee and Steve Ditko’s readers were looking for when they read a comic book, but whom might have enjoyed and benefited from a more diverse product.

Pallas, it’s odd that the people at Milestone saw things one way, and someone else saw it some other way? What? The creators at Milestone are all seeing and all knowing, and cannot be questioned? Yes, they’re black; J. Lamb is also black and sees things differently. Ta-Nehisi Coates thinks that Marvel diversity has been awesome, which would mean Milestone wasn’t even necessary. It’s almost like black people can disagree with each other.

You might as well be arguing that shitty superhero comics are for kids, so you can’t say they’re shitty. There’s lots of good, thoughtful work for kids, some of which handles race in thoughtful ways, even. (Ms. Marvel does, I’d argue.)

Saying, it’s okay because my expectations are really low — people do that with comics a lot. I think it’s insulting to both creators and audience, myself.

J. Lamb’s point and essays about whiteness integral to the superhero concept are all sound I think. I also really like Noah’s Esquire article talking about Black Lightning.

Race is problematic when its presented through genre products like super hero comics. It takes no imagination or deep insight to realize that. I’ll agree with pallas however in that consideration of audience should be taken into consideration more so than I think it has, or at least to my own satisfaction. Static’s a super hero comic, nor more or less. Does the fact that he’s black necessitate it to be more insightful or interesting than your average super hero comic character? Not really. Is that a bad thing? Looking back on Noah’s article, the final word is summed up as “Well if nothing else black audiences can enjoy mediocre product same as white audiences do.” typically dismissing the super hero genre as he’s often wont to do, which is fair enough (it is his blog anyway), but IDK if it’s saying much of anything to note that black comics can be just as staid and lame as white comics. There’s no real narrative that they would be any more insightful towards issues of race due to their nature residing in the superhero genre in the first place. Are black comic heroes completely ineffectual in the long run, added just to say they are? Maybe. But that assumes that the resulting emotions from readers white and non-white are negligible. There’s always going to be a positive effect when diversifying a cast of characters, and that’s more worthwhile I feel than worrying about the steps taken in the past.

IDK, I’m probably not getting my point across but to me it’s turning into an argument akin to pointing out that all Lt. Uhura did was answer the phone and ignoring the effects she had on people like Mae Jemison or later incarnations of Trek like DS9.

“Pallas, it’s odd that the people at Milestone saw things one way, and someone else saw it some other way? What?”

Wow, let’s back up here. Earlier in the thread I said “This is a classic damned if you do damned if you don’t scenario.”

You responded with a (in my view spurious) claim that people are really talking about “quality”. In other words, that creators writing black superhero characters are not in fact in a catch 22 situation.

Now you’re acknowledging that, in fact, all black people do not think alike, including black people who write about racial diversity issues, and I *almost* have you to the point where you are acknowledging, reluctantly, that any writer attempting to write a black character is going to be attacked for any conceivable approach to the material as writing black characters wrong.

C’mon Noah, just drop the empty rhetoric and empty assertions about “quality” and simply concede my initial point: any conceivable writer writing a black superhero comic character is going to be told by a concerned person that they are doing it wrong.

I don’t really disagree…I think there is some benefit to diversity in itself, or to positive representations of black heroes or protagonists. I think it’s also worth thinking about how particular genres might play into certain kinds of racist narratives, and how diversity doesn’t really address that (or could arguably even provide cover for it, as a kind of post-racial myth.)

I’d actually like to amend something I said in my last post.

“There’s no real narrative that they would be any more insightful towards issues of race due to their nature residing in the superhero genre in the first place.”

Lemme state that the narrative of super hero comics lead by non-white characters SHOULD be more insightful towards race I think/feel. I was talking the genre down, and Noah brings up Ms. Marvel which I would agree about. But Icon does it well I think, which I guess can be argued but I would say so. The Milestone line is easily mocked as “Black comics”, taking in a color swap being remaining as lousy as the Image and Marvel stuff of the decade, which comes off as really short sighted and lousy to me. Static was more about a believable teenager as a superhero, in this case, a black one, which I’m 99% sure hadn’t existed before then. If he’s a Spider-Man knockoff, so be it. Spider-Man never ever dealt with sex or gay classmates, or any social mores and values after Stan Lee left so the inherent value isn’t transitive or comparable. Superman never deals with race in the way that Icon did, so I find more value there too. If those characters are remembered as just more examples of the worthless-ass superhero genre, then that’s that but I’ll say that there really was more to it than what the covers…or the collection that Noah read, initially offered.

Pallas, I’m not going to concede anything; at least, not unless you can make an argument that is less helplessly confused than you’re currently managing.

The fact that people are going to disagree doesn’t indicate a double bind. Unless you think that criticism is somehow automatically crippling or hideous, and therefore unfair? Sure, everyone gets criticized for everything all the time. So what? That’s a trivial point.

You can’t take arguments about quality out of aesthetics. People are going to judge creators on how well they accomplish their goals. That’s not unfair; it’s what reacting to art means. Different people will have different takes on how well those goals are achieved. You make your arguments and then people can discuss it. In my view, the argument, “these comics have low standards and low ambitions, so you can’t think about how they work,” is a condescending and bad argument. If you disagree, make your case.

I mean, I’ve said repeatedly I think Ms. Marvel handles these issues thoughtfully. I think Captain America: Truth almost does, and then kind of falls apart — but you could see there the outlines of a comic that could be smart about these things. I think Grant Morrison’s Doom Patrol does interesting things with the racial default of superhero comics too. It’s true taht one pitfall is, all white characters, and another is, black characters who don’t really challenge the underlying white supremacist logic of superhero comics. But that’s only a double bind if you acquiesce to the idea that it’s impossible to imagine any other options.

I guess it’s arguably a double bind if you think that superhero comics are helplessly white supremacist…but it’s possible to write other genres, you know? There was a genre of KKK pulp adventure for a while back there; the fact that there’s no way to write that that is not white supremacist isn’t unfair to the genre, or whatever. I wouldn’t say that superheroes are that problematic, but if someone else wants to, you need to argue against the points raised, not start writing your hands about the unfairness of it all.

I wouldn’t say Milestone had low standards or ambitions. I wrote “the creators of these books were trying to create an adolescent power fantasy for African Americans kids”

you’re the one classifying that argument as ““these comics have low standards and low ambitions”.

Do you believe Lee/ Ditko had “low standards and low ambitious?” If so fair enough, but if not I would say that has nothing to do with race. If not I would question why the double standard. If it’s good enough for Lee/ Ditko it should be good enough for some African American creators providing an update via Milestone.

Ah had a typo above, I meant if Lee/ Ditko Spider-man sucks and Static sucks because it’s like Lee/ Ditko’s Spider-man, the reasons Static suck have nothing to do with race.

But if you’re going to claim that Static is bad but Lee/ Ditko Spider-man is good, I’m going to say you are wrong, Static is no more good or bad than Lee/ Ditko Spider-man: it’s an adolescent power fantasy for teens, and it’s not fair to pan it for not being some sort of super complex society changing treatise about race.

I think early Marvel comics are mostly crap too, sure. The art is generally better than in Static, but for instance the first Lee/Kirby X-Men comic is an evil piece of shit; Static’s better than that by a lot.

I”m not saying the comics have low ambition necessarily though. I’m saying that the defense “they’re just comics for adolescents, leave those poor creators alone,” is condescending. They made art; you can talk about whether it’s any good or not from various perspectives. Saying it doesn’t handle race in especially interesting ways, or that the art is shoddy, or that the story is eh; that’s not some sort of unfair attack on the comics. Saying it’s an unfair attack just means you think the comics aren’t worthy of attention; it’s damning.

Spider-Man is better than Static; the art’s better; the writing is better; it’s a better comic. It’s even arguably more interesting in terms of race, I’d say.

I think superhero comics can be art; I even wrote a book about one that I think is. You’re just basically repeating — “you can’t call this crap…it’s crap!” I don’t really see the point in that.

“C’mon Noah, just drop the empty rhetoric and empty assertions about “quality” and simply concede my initial point: any conceivable writer writing a black superhero comic character is going to be told by a concerned person that they are doing it wrong.” – Pallas

I disagree with this assertion.

People are, as always, encouraged to write comics and other pop culture material that can be judged on its own merits. The difficulty I sketch above involves my assertion that writing a non-White superhero protagonist necessitates some interaction with/ consideration of the notion that the superhero concept itself is racialized. We’re talking about a genre developed when Jim Crow segregation provided the unchallenged public policy state and local American governments applied to Black citizens. We’re talking about a genre developed when successful navigation of American race politics for Black people likely meant that they or someone they know would endure domestic terrorism imposed by fellow citizens and unchallenged in the courts. Why must we believe that a literary genre developed during this time has not racial component, when practically all other American popular culture of the era does?

For me, it’s completely immaterial that the Milestone creators respected the superhero concept enough to offer Black superheroes; McDuffie et al. and their contributions should not be defied by present day observers. Icon’s an alien posing as Black Republican who adopts Superman’s public interaction (demigod savior/ crimefighter) to assist lower income Black Americans whose choices he often disdains. Where the books reflect on respectability politics and reduced economic opportunities for the Black underclass, the material works (at least in the issues I’ve read.)

But when Icon cannot envision better conflict resolution solutions outside of punching the living daylights out of metahumans he doesn’t like — when Icon reverts to the moral position of a stereotypical superhero — the material’s innovation dies, and you’re left with run-of-the-mill 90’s superhero fights. That’s less interesting, and done better elsewhere.

It’s not about who characters like Rocket, Icon, and Static represent, or who the intended audience for their comics may have been (Moore wrote Watchmen for adolescent boys, too.) The question for any comic creator interested in developing a character of color should be “How does this character define their connection with this particular identity, and why should it matter to me?”

A serious attempt at answering this would prevent characters who are tangentially (insert minority status here) from standing in for meaningful diversity in panel, and would force comic narratives to stop ignoring meaningful diversity in favor of an inker’s burnt sienna hues alone. I’ve yet to find a superhero comic that accomplishes this feat effectively; just because the Milestone folk tried does not mean they succeeded.

So of course creators and their work will be evaluated, sometimes harshly. I recognize that for many, my position is heresy. But since Milestone, we’ve seen material like Captain America: Truth and Ms. Marvel and others. Gene Yang’s writing Superman soon, and David Walker will take on Cyborg. Plenty of comic creators will attempt to prove the superhero concept compatible with meaningful identity politics, and I wish them well. But too often the desire to see oneself in panel and on screen, the hope that at some point a person can stride into a comic book shop or turn on the CW and find a person of color in the gaudy lycra and skintight spandex of the superhero with neon strobes flashing from their fingertips overrides all other considerations among progressive comic fans. I oppose this.

Pallas, it’s completely fair to pan any comic for not being “super complex society changing treatise” serious about race. I should not have to assume that the characters of color I read about are only paint job Black. If so, then the audience for superhero diversity has all the ethical standing as the audience for an Al Jolson blackface revue, and I’m not paying $3.99 US for burnt cork comics.

I make the case that Grant Morrison’s Doom Patrol meaningfully engages with diversity and a critique of the superhero genre here. He’s more focused on mental and physical illness than race, but I think he does address race as well.

Just to be clear I don’t think there’s anything wrong with comics for adolescents that are empowerment fantasies.

I do suspect when you claim it doesn’t handle race in especially interesting ways you’re really reacting to the fact its too much of an adolescent power fantasy. Racism is sad, so books with black characters should be joyless and sad and not empowering.

Like The Truth, where the guy gets brain damage due to racism!

So I’m saying, no, Static doesn’t need to suffer and have brain damage and have depressing encounters with racism, it’s okay that they delivered an adolescent power fantasy instead.

I’ll say one more thing: one of my favorite superhero comics is a manga set in Japan about a girl fighting mad scientists trying to repeatedly blow up a city. So when I say “it’s just an empowerment fantasy” I mean it, I don’t think superhero comics have to address real world issues.

It’s a pretty mediocre adolescent fantasy, though. Like, Harry Potter isn’t that great, but it’s a hell of a lot better than this — more imaginative, better executed, and a lot more appealing to kids if relative success is any indication.

also, there’s the little matter of the fact that the only person who offers a racial critique is a supervillain….

I think that the fact that the only way you can think of to deal with race is to have depressing encounters with racism is kind of your limitation, not some sort of existential problem for superhero comics?

“…a manga set in Japan about a girl fighting mad scientists trying to repeatedly blow up a city.”

Mai, the Psychic Girl? The “blowing up a city” thing tends to happen a lot in manga.

Noah well apparently it’s not just my limitation, but a limitation of virtually all known writers in the entire history of comics, since apparently virtually all superhero comic books with african american characters have thus far been problematic.

J. Lamb, I do understand what you are saying about problems of “conflict resolution” and they are universal in virtually all superhero comics, as you say. There’s a Superman parody I like that sort of demonstrates the limitations of the genre:

http://www.smbc-comics.com/?id=2012

In calling for comic creators to transcend that while writing complexly about race you’re holding them to a very high standard.

I have to say, I don’t think superhero comics have tried very hard to do better over the years.

Octavia Butler’s Xenogenesis, especially the 3rd volume, can be seen as s superhero story in some ways, and as an adolescent empowerment fantasy as well….

Suat: A Certain Scientific Railgun. It’s definitely low brow. Eric Friedman wrote a review which ended with the line: “Look, take your brain out of your head and watch the girls fight the bad guys. It’s fun.”

I think we have to hold creators to higher standards in order to encourage decent material. Further, the interest Hollywood displays today in comic art should lead consumers to remember that the comics they notice in stores today, like the The Secret Service, may become tomorrow’s films, like Kingsman. Unless we desire an unceasing river of mediocrity in panel and on screen, the standards matter.

Further, the adolescent power fantasies in superhero comics are racially constructed. These books appeal to young White males by design, and the variation in that dynamic involves age, not race. It’s completely permissible for women and minorities to enjoy the material, but we should not take minority interest in the Avengers as evidence that the Avengers was designed to reflect sensibilities from all demographics. The adolescent power fantasies relayed by Marvel Comics and others reference mainstream White straight male perspectives, and token inclusion of Blacks in superhero teams or at comic conventions do not change this.

But it’s not an original sin, and it’s important to recognize this as well. Basically, I submit that there’s nothing wrong with the superhero concept’s Whiteness by itself: just that if people wish to include other groups in the concept, that inclusion requires more than an easy palette swap and culturally specific jargon (or as Noah’s discussion of Black Lightning reminds us, jive). Creators have to reevaluate what superheroes are and what they do. After that, it’s possible one may be left with a adolescent power fantasy; I don’t know. But whatever is left will almost certainly not be recognizable as a superhero, given current convention.

Wonder Woman’s a great example of this. Noah’s the expert here, but I expect that the original Wonder Woman concept didn’t call for the summary execution of a villainous telepath like some Judge Dread knockoff in a star-spangled miniskirt. Wonder Woman’s a conventionally violent superhero today; I don’t believe that an appeal to base adolescent instincts requires Wonder Woman to behave like Magog. But add in the Melian Dialogue from Thucydides or the overwhelming force doctrines applied by Ulysses Grant, Dwight Eisenhower, and Norman Schwarzkopf, and the picture clears.

Again, Whiteness as inherent to the superhero is no indictment. Whiteness is not problem for the superhero, but it is part of what makes the concept unique. If we want more racial diversity among superheroes, we should evaluate whether that’s really possible, much less a public good.

Yeah; Wonder Woman is a great example. Marston/Peter thought about the way that superheroes were a (straight) male power fantasy, and set about deliberately undermining/rethinking that. That involved a lot of different bits — reimagining violence as bondage play; shifting the genre away from pulp crime towards fantasy adventure; moving away from independent heroics towards community relationships.

It’s been done a couple of other times too; Buffy and Sailor Moon both (more or less successfully) are quite intentional efforts to take on the masculinity of superhero narratives. I feel like someone *could* do the same sort of thing in terms of race rather than gender, and there are even a couple gestures in that direction, but I don’t think anyone’s really managed as successful a version as Marston/Peter.

Probably should note that, for all their virtues, Marston/Peter were, unfortunately, rally racist.

Serious question: given Superman’s creation by two lower-class Jewish boys (and the overwhelmingly Jewish demographics of the early comics industry), don’t we need to complicate the idea of “Whiteness” here? Jerry and Joe and Jack and Will and those young men were creating superheroes at a time when many agreed that Jews were not white, when Harvard and other elite institutions still had or had only just removed their caps on Jewish enrollment/participation.

I think you can make a case that superheroes like Superman were about assimilation fantasies; ethnic minorities transforming magically into White people. That sort of ends up reinforcing J’s argument that superhero comics are designed with whiteness in mind, or to create whiteness.

While I realize you walk it back in the last paragraph, the way this post is framed ties the comic’s failure to Milestone’s diversity initiative.

Diversity didn’t make the comic bad. The creators made the comic bad. Diversity isn’t a magic bullet that can fix anything and everything. It is an end in itself, though of course it can offer more.

If the next Spiderman were black, expectations would be much higher than if the same movie were made with another white Spiderman. Expectations are always too high when it comes to black actors and black storylines–too much has to rest on too few people’s shoulders.

Huh…I really didn’t intend to tie the failure to the diversity issue, and most of the rest of the folks in comments don’t see it that way, as far as I can tell? I don’t think it’s bad because it’s diverse; if anything,I think it’s better than it would otherwise be (marginally), since non-racist mediocre genre product is better than racist mediocre genre product, all other things being equal.

Would you have taken the time to pan this comic in the first place were it not for the diversity angle? What were your expectations going in to reading the comic? Were they different than they might have been otherwise because you knew it to be more inclusive than most?

I might have! I was interested in it because I’m interested in how black superheroes work, and what folks do with them. I’ve heard that Static was good, so I thought I’d check it out.

But…I did a whole series on Man-Thing a while back because folks told me that was good, and in fact it was awful (even worse than Static, I think.) So, I’m perfectly capable of panning comics that don’t have black heroes. I’ve panned a lot of Wonder Woman comics because Wonder Woman is an interest, and most of the comics with her in them are bad.

I guess you could argue that black superheroes is an illegitimate interest…but I think I’d disagree with you. I don’t think it’s wrong to be interested in race in comics, or to talk about how it works. I don’t think it’s wrong either to hear about a comic that is supposed to handle race effectively or interestingly, and then decide it doesn’t do so well.

I take it you’re accusing me of setting the standards higher for this because it’s diverse…but I really don’t think that’s the case. I mean, I don’t say it’s any worse than other superhero comics, and I don’t say it is because I don’t think it is, really. It’s better than the really godawful Stan Lee/Kirby X-Men I reviewed a bit back. It’s better than Red Hood. Probably not quite as good as the Darwyn Cooke New Frontier I talked about a while back, though I hated that more…I don’t know. Superheroes are an interest, so I write about crappy superhero comics not infrequently. Usually I pick things that I expect to be okay, because who wants to read dreck? So, at some point I’ll probably read the Miles Morales Spider-Man, because I’ve heard good things about that, or Icon, because I’ve heard good things about that…we’ll see.

Same thing for Sleepy Hollow; lots of people I know were excited about it, partially because of its diversity. I would like to support diverse shows, and would like to watch shows that are entertaining and interesting, so I gave it a try. And it wasn’t any worse than most television — like it wasn’t worse than the Flash, which has also been highly praised. But the Flash is complete crap, unfortunately.

I’m sort of vaguely hoping to do a longer piece on diversity in superhero comics and films at some point and get someone to pay me for it, so I’m sort of doing the reading for that in bits and pieces and basically using the blog to take notes. Probably the notes are all that’ll ever get written, since I don’t have much sense of who would pay me for a longer piece, but hope springs eternal.

I think you should always write about whatever you want, and black superheroes are certainly a valid topic. Just for context, I clicked over when someone pointed out this thread as interesting on Twitter. And it is interesting! But what jumped out at me was one person finding it remarkable that an inclusive comic was mediocre, and another who seems to think that black superheroes are obliged to covey something profound about the black experience. Both positions strike me as odd.

Am I the person who is supposed to think it’s remarkable that an inclusive comic is mediocre? I don’t necessarily think it’s remarkable; I think it’s worth pointing out that diverse mediocrity is important in some ways.

Not sure who’s supposed to be saying that black superheroes have to convey something profound about the black experience…? J. Lamb is saying that diversity is often presented as a good in itself (as I do in this piece.) He’s arguing that it isn’t necessarily so; that tokenism can reify whiteness rather than challenging it. I go back and forth on that, but I don’t think it’s odd…

I read J. Lamb as literally saying that if Spider-man were black in the new film, his expectations would be much higher than if Spider-man were white.

I don’t think that’s right. J. Lamb is saying that black or white, superhero narratives are white supremacist. He’s telling you not to think the film is any better with a black Spider-Man than it would be with a white one.

He just has higher expectations than you do overall, Palls. He’s saying, for him, mediocre genre product isn’t sufficient.

EDIT: Or at least that’s my takeaway.

The real question is, why are the expectations for Black superheroes so low? What’s the point of including women and people of color in comics if gender and race have no bearing on comic writing?

When Miles Morales and Static act the same as Robin and Superboy, with the same problem solving and conflict resolution skills, does that not mean that race has no bearing on these character’s stories? How is that a diversity worth respect?

It’s been a very long time since I looked at Static. But I feel like Static is written differently that a white superhero.

It’s basically an exercise in “what if Peter Parker was black” and the answer is “He has more issues with gun violence and attempts to draw him into criminality” Parker never flirted with criminality. Noah doesn’t really present a close reading here.

You may not feel it goes far enough but I feel like he is written different.

??? Peter absolutely flirted with criminality. First episode is about him being an amoral jerk who won’t stop robberies. During the Beyonder thing he stole a golden notebook; it was presented as a big moral issue. I suspect there are other examples…Static even gives up superheroing the way Spider-Man always was.

Spider-Man kind of presented a racialized immigrant experience in the first place I think. It’s a little more explicit in Static, but the suggestion that there’s some sort of major change in tone or presentation doesn’t hold up, I don’t think, at least not in the issues I read.

Peter is an amoral jerk but not stopping a criminal really isn’t a crime. You’re kind of stretching there. It’s really not a crime to refuse to stop a thief.

I have no idea what this Beyonder thing is or when it happened but it’s not a core part of Spider-man’s story.

Like I said I can’t back my reading up because it’s been a very long time since I looked at Static and don’t have a copy offhand, but I did get the sense there were differences.

You yourself said Noah that the villain tries to recruit Static by making a racial argument. That would seem to be a difference in how he’s written due to race.

You may feel it’s poorly done but my point is he’s not written the same as if he were white.

In the case of Miles Morales, which I read more recently, he wins a lottery to get into a good school, the subtext being things are so stacked against him because he’s black that going to a good school is akin to a miraculous Spider-bite.

You may not consider it great writing but there are creative choices related to race that can be picked apart by a close reading.

I think there are a couple of racial choices, yes; they’re not handled very well though.

Spider-Man’s ambivalence about his heroism is pretty central to his character. So is the fear and dislike he generates — a fear and dislike which is I think a kind of buried racial marker. Like I said, you could argue pretty easily that Spider-Man is actually more interesting in terms of its attentiveness to race than Static is.

That is, the early Ditko Spider-Man is an agonized parable about the immigrant experience, passing/not-passing, and assimilating/not-assimilating. Static is a kind of half-hearted riff on black upward mobility and assimilation with most of the anxiety and pain shrugged off.

Not that the early Spider-Man is great, necessarily; it’s kind of so-so (though you could argue that it’s unwillingness to deal with the issues it raises is thematized in terms of assimilation.) But it’s better than Static, I think, not least because it’s handling of race is better (not good, but better.)

Hello all

I wanted to share with you my new 60 second book trailer based on my book Volonians. Share if your inspired.

http://youtu.be/JPmExCAZj-Y

Carlos

This is the most interesting discussion I have read online in a long time. I look forward to tracking down the participants individual blogs, writing forums, etc. Thanks for putting your thoughts in a public forum to inspire further thinking and discussion.

IK