Thematic connections and similarities can be seen between scenes in films by the Spaniard Luis Buñuel and multiple works by the Italian Michelangelo Antonioni. Two of the 20th century’s greatest directors, Buñuel and Antonioni competed for recognition and took turns winning the same awards on alternative years at film festivals. For example, Antonioni’s L’Eclisse competed and won against Buñuel’s Exterminating Angel for the special jury prize at the 1962 Cannes Film Festival—and so, both directors were doubtlessly in the same room at multiple times in their lives. However, I have been unable to prove that they had any personal interaction. I have also been unable to find Buñuel speaking of his contemporary Antonioni anywhere in the record. For his part, Antonioni mentioned Buñuel only once, when in an interview, he was asked about the method of directing from a monitor placed off-set that he used for the celebrated long take at the end of The Passenger and he said, “Buñuel always uses it” (Antonioni, 183). In fact, Buñuel did direct his films from a separate room where he was able to watch what was happening on a monitor, because he was increasingly hard-of-hearing. At any rate, it can be assumed from this fact that at the very least, Antonioni was familiar with Buñuel’s modus operandi.

Antonioni’s great Italian contemporary Federico Fellini not only lists Buñuel as the director of one of his favorite films of all time, The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie from 1972, but Fellini further qualifies him as “a filmmaker of genius. I might say that Buñuel is the greatest filmmaker of all” (Costantini, 200). Buñuel’s biographer John Baxter also claims that his subject considered Fellini to be one of his favorite directors, but says that they both “shared the great directors’ discomfort at seeing the work of their competitors”—so it may be that Antonioni kept an instinctive distance, or the lack of hard evidence of any interchange between Buñuel and Antonioni might simply reflect an omission of inquiry by the film historians lucky enough to speak to those directors (Baxter, 278). Not finding them talking about each other in print and not being able to definitively place them together does not preclude a mutual respect, or even a one-sided influence by one director to the other. And regardless, the correspondences between their films are there.

One of the films that seems to have informed Antonioni, because of his use of certain key elements in several of his films, is Buñuel’s Exterminating Angel. In this 1962 feature, a group of wealthy people arrive at a huge mansion just as the servants leave under various pretenses. The dinner party congregates in the dining room, where they become inexplicably trapped. There is no direct rationale given, psychological or otherwise, for their apparently self-imposed imprisonment. No obstacle stands between them and the next rooms, much less the outside world, but they cannot bring themselves to pass though the doorways of the single confining room. As Virginia Higgenbotham notes, “It is, simply, a crisis, and the guests are responding to it the way the bourgeoisie usually responds to crises—by doing nothing…the fear of being the first to act, the terrible inertia imposed by conformity upon the group…has rendered them helpless” (153). Over a period of days and then weeks, the party degenerates. They use large urns in a closet for toilets, they begin to starve, they turn increasingly filthy and some of them begin to manipulate the others to fight amongst themselves. They pull pipes from the wall to get water and eventually smash up the very walls themselves for firewood. Their predicament functions as a metaphor for people who are trapped by their self-identification of class; a clue to support this interpretation may be a piece of broken wallboard that hangs down from the top of the impassable doorway to resemble the blade of a guillotine.

The upper-class group’s chaotic and degenerate destruction of a enclosing space is echoed in Antonioni’s Red Desert of 1964, in the scene when a group of Giuliana’s friends or acquaintances meet in a shack by a dock. Within the tiny structure is a smaller enclosed red-painted room. The group of men and women all cluster into this confined space and begin to hint broadly of engaging in an orgy. There is a clear distinction made regarding class; the people within the red room all speak with upper middle class accents, but when another couple enters the shack from outside who speak with lower-class accents, they are not asked to join the group and they leave. As the scene progresses, a noise is heard from outside and the group emerge from the red room. A huge cargo ship is seen to pass outside, disturbingly close to the window and the party proceeds to rip the red room apart, smashing its walls for firewood. Although the commentary track that accompanies the Criterion DVD of Red Desert states that “there does not appear to be any particular significance to this destruction of the interior wall,” little or nothing in an Antonioni film is accidental. Murray Pomerance equates the room with an interior bodily cavity as he asks, “What is that bloody chamber, a womb of sorts? A coliseum? Now with a wall torn down, it radiates at one side of the hut, its interior a messy shambles of pillows and mattresses where these bizarre siblings had lain and out of which they were born” (99). According to Ned Rifkin, it is more about the act of violence as a substitute for sexuality and color reflecting emotion. Rifkin says that when one of the characters puts his foot through the red wall, it shows:

…the weak moral fiber which is present. When Mili and Corrado begin dismantling this wall in order to stoke the fire in the stove, the equation of sexual activity and this destruction is explicitly established…the abortive ‘orgy’ is less exciting for the participants than this act of feeding the flames of passion (red fire) with the fabric of the shack (rotten red wall) (99).

The director observed to his contemporary director Jean-Luc Godard about the Red Desert scenes that take place in a factory, “The interior…was painted red: two weeks later the workers were fighting amongst one another. It was repainted in pale green and everyone was peaceful” (cited in Rifkin, 99). The color red has an enraging affect on humans who are forced to spend time within it, or in its proximity, just as a crimson flag does for a bull. It should also be pointed out that enclosed spaces are a time-worn trope of, and catalyst for, dramatic conflict.

The more pervasive motifs that Antonioni implements are seen first much earlier, in Buñuel’s second film, the 1930 L’Âge d’Or, which was intended to be a follow-up collaboration with painter Salvador Dalí after the pair’s 1929 classic Un Chien Andalou, but the two surrealists fell out just before the production commenced and so Dalí was much less involved with L’Âge d’Or than he had been with their previous effort. It seems certain that Antonioni was familiar with such a seminal work; L’Âge d’Or was, in fact, one of the first sound films ever produced in France, and so by default in Europe. The film which incorporated aspects of the Marquis de Sade’s novel 120 Days of Sodom was made with the backing of a Jewish/American aristocrat who was descended from de Sade, Marie Laure de Noailles, and her husband the Vicomte Charles. The film was famously the subject of much controversy when it was denounced by fascists. A gang of hooligans organized by “The League of Patriots” and “The Anti-Semitic League” rioted at Studio 28, the Paris theatre where it premiered and as a result, the French government in a misguided attempt to avoid conflict banned the film for more than forty years. All but three prints of L’Âge d’Or were destroyed. These are all facts that Antonioni would certainly have been aware of, given his long tenure as a film critic.

I suggest that two scenes in L’Âge d’Or influenced Antonioni’s later work. My first evidence of that comes in one of the introductory passages in the film, which depicts a group of Catholic bishops sitting atop a coral island, who are later seen in the same positions, but decomposed into skeletons. The ominous island that the protagonists of Antonioni’s 1960 feature L’Avventura become trapped on has some similarities to this location. A young woman from a group of people on a temporary stop during a recreational sail disappears from the island that is really just a naked, rocky outcropping surmounted by an apparently deserted hut. Ian Cameron and Robin Wood note that in L’Avventura “the surroundings shape the events. The island, barren and unfriendly, breaks up relationships, isolates the characters from each other” (72). Some of the group ostensibly continue the search for their missing friend for the rest of the film, but they seem distracted by their sexuality, as observed by William Arrowsmith: “the modern Mediterranean nomads of L’Avventura sink, to lose themselves…(on) abandoned islands where life began…Against the background of these immensities the erotic impulse becomes obsessive” (38). The connection between human physicality and the landscape is emphasized by several scenes of men and women embracing against the stark sky, their turning heads and shoulders like islands themselves, pushing over the horizon line of the bottom of the screen.

Another scene that is reminiscent of the “bishop’s island” from L’Âge d’Or is the one in Antonioni’s Red Desert that visualizes a “living island” from the story that Giuliana tells her son. The clean beauty of this ostensibly “imaginary” scene deliberately opposes the polluted, artificially augmented images that represent Giuliana’s “reality” in the rest of the movie. The surfaces of the island’s rocks are deliberately shot to resemble fleshy, writhing human bodies and they are heard by the solitary young girl there (who can be taken to substitute for Giuliana) to emit a wordless song, a siren’s voice that leads her into the sea. For Pomerance, this tactile and aural humanization of inanimate objects signifies “a loss of personal discreteness, a dissolution of the individual self in the surrounding objects and situations of life” (105). Arrowsmith extends this idea to ask, “if the rocks in the island tale are like flesh, why might everything in the film not represent life? All the machines are human constructs, every pipe was molded and soldered by someone, every ship chugs up the canal under the fingers of a navigator at a wheel” (106). As he will in other films, in different ways, Antonioni makes inert and earthly surfaces interface with the human body.

The most striking correspondences I have found between Buñuel and Antonioni, though, are rooted in a scene in L’Âge d’Or in which a solemn ceremony for the laying of a foundation is interrupted by a man and woman who couple violently in the mud. They are pulled apart by the crowd of spectators and the now-enraged man runs off and kicks a dog; then the camera proceeds to follow him through a series of obtuse misadventures. The scene of the lovers entwined on the wet ground is widely noted in the literature about the film; from the citing of the man’s “amorous egoism” (Gaubern and Hammond, 49) to the invocation of an “intense love (which) tears the prejudices, inhibitions and laws of society to shreds” (Kyrou, 22). Buñuel says that his film is “about passion, l’amour fou, the irresistible force that thrusts two people together, and about the impossibility of them ever becoming one” (Buñuel, 117). What Buñuel’s scenario describes as a “fiercely lascivious embrace” may have represented for the sexually repressed director, who always reviled his Catholic upbringing, a “kind of blazing passion that was never part of Buñuel’s experience,” a virility displayed by the “kind of man he may well have wanted to be” (Edwards, 72).

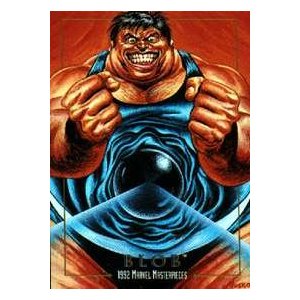

From Luis Buñuel’s L’Âge d’Or

The writer Henry Miller, himself no stranger to erotic self-indulgence, qualified the scene and the entire film as representing:

…the death knell of the race. Man is doomed to perish; he has betrayed his instinct, he has sacrificed everything to his intelligence…What has man done with his instincts? Denied them. The summation of all his laws, his codes, his principles, his moralities, his totems and taboos, what does it yield? Sterility. Death. Annihilation…Mired in his art, suffocated by his religion, paralyzed by his wisdom. That which he glorifies is not life, since he has lost the rhythms of life, but death (cited in Kyrou,183-185).

The themes shown in Buñuel’s later work have some continuity with L’Âge d’Or, but the correspondences that I note in this paper are not necessarily meant to equate his intent in that early film with that of Antonioni. Still, a recurring motif of couples engaged in romantic or coital acts in the mud and in general, images that conflate sex with dirt or dust and scenes of people interacting with the ground, with the Earth itself in various ways, can be observed time and time again across Antonioni’s oeuvre.

The first instance can be found in his 1955 film Le Amiche about a group of female friends. In a famous key scene, they all take a day at the beach and as they walk by a couple who are necking while lying in the sand, Momina ignores the female’s agency to tell Clelia, “I don’t think a man feels anything for a woman he kisses in public.” In other words, such scenes display an aggressive masculine ego. Pierre Leprohon observes that Le Amiche depicts “not only the desolation of private human relationships but also a social class whose vanity and uselessness were bringing about its own disintegration,” which apparently agrees with Buñuel’s stated object for his frenzied pair (47). At any rate, the image is sufficiently striking for Antonioni that it becomes imbedded in his cinematic vocabulary.

A second set of incidences can be seen in Antonioni’s Il grido, released in 1957. The film pointedly depicts people struggling to survive in the devastated and industrially polluted postwar environment of the Po Valley. In an early scene, women are shown walking in heels in the stark countryside. A torrential rain falls and in close-up, wet dirt is seen to be splashed up on their bare legs. The pointed visual blending of mud and high fashion eroticizes filth. The protagonist Aldo can only ever love one woman, his betrothed Irma. Arrowsmith describes Aldo as “rooted to the ground of his being” in the scene where he sits with Irma under a tree, literally on the roots and on the muddy ground (26). She informs him there that she has fallen in love with someone else. After slapping her around publicly in the town square, he then absconds with their daughter Rosina. Arrowsmith asserts that all that then befalls Aldo is due to:

…an infinity of solitude, the recognition of human smallness in a post-Copernican universe or even an anonymous mass society, and then the consequent erosion of mere responsibility, automatism—leads the individual directly to the malaise of Eros. Love, as an enduring or even stable bond, disappears, replaced by serial affairs, the desperate attempt to make Eros, by sheer quantification and repetition, an anodyne against reality, a shelter of human warmth against immensity (26).

This view of Antonioni’s vision of contemporary love again does not misalign with that of Buñuel. If people are able to find love in the modern world, it is not because of society, but in spite of it and the larger, uncaring universe. In Il grido, Aldo and Rosina wander to be eventually taken in by Virginia, the owner of a gas station, with whom he reluctantly begins a relationship. One day as Aldo is walking with Virginia and Rosina, the adult pair inexplicably desert the child to go off by themselves and they embrace while laying on the ground near some large wooden wire rollers. Rosina comes upon them and the upset girl runs away. This incident is the cause of an estrangement from her father and soon he places her on a bus to be returned to her mother. According to Sam Rodie, “it ruins everything…A series of presences cancel out one another only to be cancelled out in turn….at the precise moment that Rosina leaves and Aldo is ‘free’, he turns his back on Virginia and leaves as well as if he has lost in these cancellations even more of himself, and of others” (95). Aldo moves on to live for a time with another woman Adreina in a flooded landscape, but increasingly he is a shadow man without substance. All that is left to him is to try to return to visit Irma and Rosina, but through the window of Irma’s house, he is depressed to see her with her new partner. Irma glimpses him and follows as he returns to the industrial site he had worked at to climb the tower where he was first seen at the outset of the film and then, he is killed when, exhausted, he loses his balance and falls to the ground at her feet. He has met and impacted with the “ground of his being.”

Another instance of the grappling of earthbound lovers is in Antonioni’s 1961 feature La Notte. Giovanni and Lidia’s failing marriage ends after an all-night party on a vast estate, as they unsuccessfully make love in a sand pit on a part of the lawn that has been given over to be a golf course. Rifkin cites “Giovanni’s feeling of futility…as he lies on top of Lidia, more like a wrestler than a lover, desperately groping for something which they no longer share” (29).

From Michelangelo Antonioni’s La Notte

Giovanni and Lidia’s feeble final encounter is seen by other writers as a “last desperate attempt to substitute physical contact for emotional connection” (Orban, 22) wherein “a complete evacuation of the human is achieved, however briefly, as a return to the mute expressiveness of the natural world” (Brunette, 71). The camera pulls back and the film ends with only a view of the landscape.

There are no muddy sex scenes per se in Red Desert, but in addition to the “fleshy island” tale previously noted, Antonioni’s disturbed heroine Giuliana relates a dream she has had of sinking into quicksand—and there are depictions of a muddy, polluted landscape enhanced with grey spray enamel, a technique that the director also used for many other locations throughout the film, including a patch of woods that was sprayed white, to no avail as it turned out, since the effect turned out to be unfilmable. Later in Zabriskie Point, Antonioni used paint to blend the human figures shown writhing erotically with the desert landscape (I will return to this scene presently). Also in Red Desert, at the factory a huge blast of steam obscures the view of the people in the scene entirely, a visual motif which recurs later on the dock, when Giuliana’s companions dissolve into a thick fog. Figures vanishing into clouds of vapor or dust is another trope that is present in many Antonioni films.

But to return to the repeating motif of bodies on the ground, it next turns up in reflexive form in Blow Up from 1966, when the photographer Thomas stands, snapping his shutter, dominantly straddling the model Veruschka who is splayed on the floor. Both of Antonioni’s visual tics that are noted above are blended when the corpse of a man on the ground in the park that Thomas’ investigation has uncovered dissolves into illegibility in his successive close-up prints. He goes back to the park to confirm the corpse’s existence, and finding it, he touches it, he stands over it, echoing his earlier pose over Veruschka, but this time he is camera-less (emasculated). It seems that the photographer doesn’t perceive the dead man as the victim of a crime that he should be reporting to the police. For him, the corpse is an object that seems only to have much the same novelty value as the huge propeller that he found in the antique shop earlier and then went back to purchase. But by the time he returns to the park with a camera, the cadaver has vanished. Matilde Nardelli asserts that this scene “occasions for the photographer his most lucid, if not only, moment of self-awareness in the film” ( in Rascaroli and Rhodes, 77). In the end, the body of the dead man is less real than the propeller; having disappeared, the corpse and its dissolute image have no evidentiary substance, in fact they have the same degree of reality as the imaginary tennis ball that the mimes pretend to play with—or indeed, the fictional Thomas (because the self-awareness of the viewer also comes into play here), since he is then himself abruptly erased from the image.

In Antonioni’s revolutionary but universally misunderstood 1970 feature Zabriskie Point about the American hippie movement of the 1960s, his protagonist Mark becomes so disillusioned with the inequities of human society after witnessing the murder of an African-American protestor by the police that he literally disconnects himself from the ground by stealing a small plane and flying it to the desert. There he joins with a young woman to enjoy a brief moment of freedom, which Antonioni expands into an allegory for the youth movement. Murray Pomerance relates that the director intended to shoot a massive “love-in” in the part of Death Valley that the film is titled for: “I want to see 20,000 hippies out there making love, as far as you can see.” A park ranger charged with facilitating the project wasn’t amused: “The answer to that is a flat no” (170). Even if Antonioni could have somehow ignored or evaded the Park’s conservative guardians, his production manager Bryan Gindoff says that “the cataclysm amounted to twenty thousand people times $29.15 a day plus meals and penalties and overtime; it was more than I could multiply in my head” (cited in Pomerance, 170). The scene was scaled down, but it remains the most ambitious of Antonioni’s Buñuelian earthy love scenes. In the finished film, the protagonists and dozens of other couples as well as bisexual clusters of lovers are photographed making love onscreen in the nude as Jerry Garcia’s instrumental track meanders lyrically. The lovers roll together, roiling in ecstasy and then they dissolve in an apotheosis of dust. According to Pomerance, “In Antonioni’s sequence, body is finally land, land is body; heat is dust; sound is rhythm…Mark and Daria sense that they have stopped being themselves, that they are part of something vast and historical and old, called life” (173). The scene depicts humans reverted to a primordial state.

From Michelangelo Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point

In the run-up to the film’s climax, Mark is senselessly shot dead by the police after returning the plane to the airport he had stolen it from. According to Rifkin, in the film Antonioni uses the desert scenes to represent “a release from modern urban life’s oppressive conditions” and they provide “a context for man’s moral relationship to his perceptual understanding of the world.” By contrast, the urban locations are presented as “analogous to the deathly elements of modern life…in all, it is not surprising that Mark is killed when he leaves the desert for the city,” Rifkin concludes (32). The film’s extremely negative reception at the time of its release and for many years afterward indicates a critical breakdown, if not systematic suppression.

For example, reactionary critic Vernon Young is racist when he refers to the multicultural participants in the believably staged activist meeting at the beginning of the film as “savages” and he is dismissive of the goals and integrity of the idealistic youth movement when of Mark, he says, “The lad…is a lawless punk with no shadow of a claim to any opinion which should be taken seriously.” Young goes on to express ignorance or denial about later documented activities of police and intelligence forces against the American left: “I’m not just ready to believe (despite my aversion to the American police) that cars-full of State patrolmen would be mustered to corral one youngster in a stolen plane, or that he would be shot to death, unseen and without provocation” (538). Even a relatively sympathetic commenter such as Seymour Chatman disrespectfully states, “One almost wishes that the film had been suspended in mid production and that the footage had come down to us unedited, like that of Eisenstein’s Mexican film, so that each of us could have figured out how to put it together,” as if everyone but Antonioni would know better than he how to make his film (168). The hostility directed at Antonioni was not limited to the post-release reaction. Angelo Restivo relates that since it was a MGM-financed film, the director’s trusted Italian crew members had been “doubled by paid American union” workers who were “conservative, disparaging and even went so far as to attempt to sabotage the filming on occasion” (in Rascaroli and Rhodes, 83). The film ran over-budget for reasons outside of Antonioni’s control and on release, it lost money. In these ways it was made by its legions of detractors into such a commercial disaster that five years would pass before Antonioni was able to produce his next feature film, The Passenger.

In summation, unlike the products of Hollywood, the questions posed by the films of Buñuel and Antonioni may not have clear-cut answers, but those questions are often themselves the subject of their films. Antonioni’s films famously resist closure or pat explanations, even those he made for MGM. One might interpret the actions of the couple in L’Âge d’Or to be that they are so overcome by passion that they are unaware of the spectators, but it also might be that they indulge a performative gesture for specific effect, making the private become public. Similarly, some of Antonioni’s uses of the device can be interpreted as representing abrupt, desperate passion, some depict exhibitionist displays, others a melding with the dust from which we sprang and some seem intended to show that the essential nature of man is animalistic.

Most observers then and now trivialize the sexual scene in the desert in Zabriskie Point through a bourgeois lens to represent the fad of “free love” and the whole film as an attempt by an aging, foreign director to depict a cartoonish American hippiedom. However, it becomes apparent that the Death Valley sequence is actually the culmination of the series of Buñuelian “grounded” love scenes that occur deliberately throughout Antonioni’s body of work. As well, this specific instance and indeed, the whole film (including its incendiary apotheosis) serve to reclaim the noblest ideals of the psychedelic generation from the mainstream media where they have been co-opted. Seen also as perhaps an antidote to the scenes of isolated people wandering futilely through polluted, devastated landscapes that Antonioni shot for Il grido and Red Desert, his desert love sequence in Zabriskie Point envisions humans returning to a pre-historical state of being, or perhaps reaching for post-historicity, as they attempt to become one with each other and the Earth, in the end a much saner approach than the oblivious environmental disregard that has brought our planet to the brink of disaster.

Thanks to Giancarlo Lombardi and Marguerite Van Cook.

Film sources.

L’Âge d’Or. Dir. Luis Buñuel. Perf. Gaston Modot, Lya Lys, Caridad de Laberdesque. Vicomte de Noailles, 1930. Kino, 2004. DVD. Web: Youtube 20 March 2014. Link.

Exterminating Angel. Dir. Luis Buñuel. Perf. Silvia Pinal, Jacqueline Andere, Enrique Rambal. Producciones Gustavo Alatriste, 1962. Criterion, 2009. DVD.

Il grido. Dir. Michelangelo Antonioni. Perf. Steve Cochran, Dorian Gray. SpA Cinematografica/ Robert Alexander Productions, 1957. Kino Video, 2000. DVD.

L’Avventura. Dir. Michelangelo Antonioni. Perf. Monica Vitti, Gabriele Ferzetti. Cino del Duca/ Produzioni Cinematografiche Europee/Societé Cinématographique Lyre, 1960. Criterion, 2001. DVD.

La Notte. Dir. Michelangelo Antonioni. Perf. Marcello Mastroianni, Jeanne Moreau, Monica Vitti. Nepi Film/Silver Films/Sofitedip, 1961. Criterion, 2013. DVD.

Red Desert. Dir. Michelangelo Antonioni. Perf. Monica Vitti, Richard Harris. Film Duemila /Federiz /Francoriz Production, 1964. Criterion, 2010. DVD.

Blow Up. Dir. Michelangelo Antonioni. Perf. David Hemmings, Vanessa Redgrave, Jane Birkin. Bridge Films/Carlo Ponti Production/Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1966. Warner Home Video, 2004. DVD.

Zabriskie Point. Dir. Michelangelo Antonioni. Perf. Mark Frechette, Daria Halprin, Rod Taylor. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer/Trianon Productions, 1970. Warner Home Video, 2009. DVD.

Print sources.

Antonioni, Michelangelo. The Architecture of Vision. Eds. Carlo di Carlo and Giorgio Tinazzi. New York: Marisilio, 1996. Print.

Arrowsmith, William. Antonioni: The Poet of Images. Ed. Ted Perry. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995. Print.

Baxter, John. Buñuel. New York: Carroll & Graf, 1994. Print.

Brunette, Peter. The Films of Michelangelo Antonioni. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998. Print.

Buñuel, Luis. My Last Breath. Tran. Abigail Israel. London: Vintage, 2003. Print.

Cameron, Ian and Robin Wood. Antonioni. New York: Praeger, 1968. Print.

Chatman, Seymour. Antonioni or, The Surface of the World. Berkeley, Ca: University of California Press, 1985. Print.

Costantini, Costanzo, Ed. Conversations with Fellini. Trans. Sohrab Sorooshian. New York: Harcourt Brace & Co. 1995. Print.

Edwards, Gwynne. A Companion to Luis Buñuel. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Tamesis, 2005. Print.

Gubern, Román and Paul Hammond. Luis Buñuel: The Red Years, 1929-1939. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2012. Print.

Higginbotham, Virginia. Luis Buñuel. Boston, Mass: Twayne Publishers, 1979. Print.

Kyrou, Ada. Luis Buñuel: An Introduction. Trans. Adrienne Foulke. New York: Simon and Shuster, 1963. Print

Leprohon, Pierre. Michelangelo Antonioni: An Introduction. Trans. Scott Sullivan. New York: Simon and Shuster, 1963. Print.

Orban, Clara. “Antonioni’s Women, Lost in the City.” Modern Language Studies 31. 2. (Autumn 2001) 11-27. Print.

Pomerance, Murray. Michelangelo Red Antonioni Blue: Eight Reflections on Cinema. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011. Print.

Rascaroli, Laura and John David Rhodes, Eds. Antonioni: Centenary Essays. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. Print.

Rifkin, Ned. Antonioni’s Visual Language. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press, 1982. Print.

Young, Vernon. “Reflections on Two American Films.” The Hudson Review 23. 3. (Autumn 1970) 533-539. Print.