In a recent post on the definition of comics, I suggested that one of the important features that distinguishes comics from other pictorial art forms is that when we consume comics we are experiencing the work the way that we typically experience images — that is, comics are narratives where we look at (rather than merely read) the narrative. In particular, it follows that:

In a recent post on the definition of comics, I suggested that one of the important features that distinguishes comics from other pictorial art forms is that when we consume comics we are experiencing the work the way that we typically experience images — that is, comics are narratives where we look at (rather than merely read) the narrative. In particular, it follows that:

(P1) When reading a comic we experience the text the way we normally (i.e. outside of comics) experience images

This still seems, in some sense, right to me (and, of course, Will Eisner agreed “Text reads as image!”, Comics and Sequential Art, 1985).

In the discussion that followed, summarized and discussed in this follow-up post, Peter Sattler suggested that “Comics are what happens when textual reading habits are activated in a visual (image-centered) field.” In other words, Sattler’s view, although not on the face of it incompatible with my own, seems to be a mirror-image of it: On his account, comics are (or, at least, minimally involve) something like structured images, where we read (rather than merely look at) the images in question. Thus, we get:

(P2) When reading a comic we experience the images the way we normally (i.e. outside of comics) experience text.

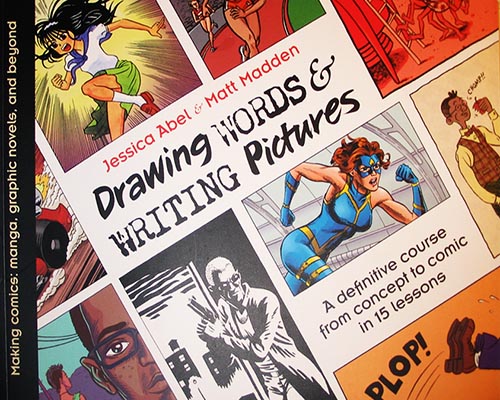

Note that Jessica Abel and Matt Madden codified a version of both of these ideas (but from a production orientated, rather than a consumption orientated, perspective) in the title to their first how-to book on comics!

Note that Jessica Abel and Matt Madden codified a version of both of these ideas (but from a production orientated, rather than a consumption orientated, perspective) in the title to their first how-to book on comics!

Reading a text (of whatever sort) seems both phenomenologically and structurally very different from looking at something, however: When reading, we are interested in largely conventional semantic relations between linguistic units and their referents, whereas with looking we are often interested either in the bare appearance of the thing being looked at, or in relations of resemblance and representation holding between depiction and thing being depicted (which are often somewhat, but rarely completely, conventional). In short, reading feels different from looking, and the mechanisms underlying reading are (so far as we understand these things) quite different from the mechanisms underlying looking at something. Thus:

(P3) Looking is phenomenologically very different from reading.

The paradox arises when we note the following fact, apparent to anyone who reads comics on a regular basis:

(P4) We experience the content of comics in a unified manner.

In other words, we don’t first decode the content of some parts of the work via reading, and then decode the content of other parts of the work via looking, and then incorporate these two very different sorts of content into a unified whole in some sort of conscious three-step process. Instead, the process is seamless and smooth, with no apparent difference felt between what is read and what is looked at.

But how can this be? How can our experience of comics be unified in this way if it is composed of two very different experiential modes – modes that are noticeably different in the way that they ‘feel’ to us? Shouldn’t we be able to detect the shift from looking to reading and back to looking when it happens? If so, then it looks like (P1) through (P4) above are jointly inconsistent (or, at the very least, seem to be in tension with one another). This is the paradox of the comics experience.

Now, we could just stop here, and admire the fine paradoxical pickle into which we seem to have gotten ourselves. A part of me would be fine with that – I have already written two books with the word “paradoxical” in the title, so I have no problem getting excited about new paradoxes. But maybe we don’t have a genuine paradox here.

We do have a puzzle, however – one we need to solve. It is clear that reading and looking are two distinct kinds of experience, with their own mechanisms, features, and feels. It is also clear that seasoned comics readers are able to employ both of these experiential modes simultaneously, and are able to switch from one to the other and back again seamlessly without even noticing they are doing it. What is not clear at all, however, is how this works (In other words, don’t waste your time or mine trying to convince me in the comments that we actually do this. It’s obvious we do. The point is we need an explanation of how we do it, and we don’t have one). Thus, what we need is an account of the various ways that comics generate meaning that explains how these very different modes combine to produce a single unified meaning.

We do have a puzzle, however – one we need to solve. It is clear that reading and looking are two distinct kinds of experience, with their own mechanisms, features, and feels. It is also clear that seasoned comics readers are able to employ both of these experiential modes simultaneously, and are able to switch from one to the other and back again seamlessly without even noticing they are doing it. What is not clear at all, however, is how this works (In other words, don’t waste your time or mine trying to convince me in the comments that we actually do this. It’s obvious we do. The point is we need an explanation of how we do it, and we don’t have one). Thus, what we need is an account of the various ways that comics generate meaning that explains how these very different modes combine to produce a single unified meaning.

Any such account will likely draw on psychology, linguistics, philosophy, and other fields that concentrate, in different ways, on how we turn perceptions and actions into meaning. Unfortunately, unlike some other disciplines, psychology, linguistics, and philosophy* have not paid much attention to comics. Maybe its time to change that.

So, in the PencilPanelPage tradition of ending with a question, I’ll end with this: How do reading and looking differ, and how are the combined in the experience of reading comics?

*I am not saying that there is no good research on comics in psychology, linguistics, or philosophy as applied to comics. After all, I am a philosopher who writes pretty prolifically on comics, and my pal and fellow PencilPanelPager Frank Bramlett is a linguist. But the few there are just ain’t enough.

Is there neuroscience on this? Do reading and looking affect the same areas of the brain?

Neil Cohn’s done extensive work on the “reading pictures” paradox. His website is here: http://www.visuallanguagelab.com/

It looks like he’s drawn from neuroscience for some of his studies, though I haven’t read them.

There’s work in visual rhetoric and social semiotics that draws on insights from neuroscience on how we “read” multi-modal texts. From what I’ve read, there’s little question that the brain processes words and images differently, and through discrete neurological pathways. Moreover, there’s some research to suggest we process images fast than we process written language. Of course, things get fuzzier once you look into the phenomenological dimensions of reading multi-modal texts.

Anyway, Cohn is active online and I hope/suspect he’ll weigh in on this, as I’m driving way past my headlights here.

Noah Berlatsky sent me over here after I heard my ears burning from that last comment (thanks Nate!)…

But yes, I’ve done quite a lot of work on this issue over the last 15 years, the basics of which is summarized in my book, The Visual Language of Comics (bit.ly/1pb5pNo). (Also, I’ve found that there’s actually a lot more out there that’s been done than people realize. I’ll have an edited book with this stuff later this year, but citations galore in my papers and there are lots of summaries/reviews of papers on my blog).

While I do a substantial amount of theoretical work, my research also does a lot of psychology experiments, with my main focus on neuroscience looking at brainwaves. So, my main question is: how would you distinguish “looking” from “reading”?

Our work using eye-tracking (currently under review) basically shows that similar reading patterns are used between comic panels as across text. There is very little freeform scanning, mostly directed movements, and eye regressions typically move linearly to adjacent images. Eye-movements within images are typically more regularized too, focusing on specific features informative to the sequence (and not scanning details in panels). This is different than what eye-tracking shows for individual images, which are more dispersed and less systematic.

If we’re talking about what the brain is doing… my work has shown the same brain responses to processing sequential images as to sequential words. All these papers are online (www.visuallanguagelab.com/papers.html), and there’s a whole chapter on it in my book (bit.ly/1pb5pNo). However, a brief summary of one of those studies was summarized in a short video here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dU7c9euTso4&spfreload=10

Maybe this is so obvious as not to be worth mentioning, but. It seems to me that at least some of what Roy and Neil are each saying applies only to relatively competent comics — competent in the sense that the sequences are straightforwardly processed. Incompetent comics stump the eye.

Sticking to phenomenology (since I know sfa about neuro or linguistics), this suggests: (i) it’s harder to make minimally competent comics than to make minimally grammatical sentences. (Independently of one’s basic ability to draw representationally, I mean). (ii) reading incompetent comics feels more like looking than reading. Actually, it feels more like: try to read, get stumped, switch to looking in order to find the best order, then read again.

Just an added note related to this discussion. I just noticed this paper that came out in February arguing that there is overlap between the neural networks involved in understanding meaning in language and vision:

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1053811914009410

This doesn’t surprise me too much (similar results have been around for awhile), but it is pertinent to what was brought up here.

So I’ll admit right off the bat that I wrote this post hoping that I would get either Neil (or someone who knows Neil’s work) in on the action.

I think that Neil has nailed one of the most important questions: What is the difference between reading and looking? One way to answer this is with neuroscience (or physiological stuff more generally). And Neil’s points about the eye-tracking studies is really interesting in this regard, since it suggests that the way we process images when they are embedded in comics is different from the way we process them when not so embedded. In short, we ‘read’ these panels rather than ‘look at’ them.

Now, this gets really interesting when we ask what a particular image means on its own, and what it means when embedded in a comic. Of course, independent of this whole reading/looking issue, the image will likely have a different meaning in the comic, since it gets its meaning in part due to its context (the meaning of images is extremely context-sensitive – a point masterfully made by John Byrne in the notorious jumping-rope-naked issue of Sensational She-Hulk). But even apart from this, it seems like the different ways we process images, when isolated, or when part of a comics sequence, entail that we will understand the meaning of the image differently based solely on the fact that it is part of a comic (and independently of how the content of other images in the comic contextually affect the content of the image in question).

This has practical ramifications. For example, here is a way of analyzing a comic that turns out to be deeply mistaken, if all of the above is correct: First, determine what each individual image means in isolation. Then determine what the comic as a whole means (which we be partially compositional, incoporating the individual meanings of the images, and part contextual, where meanings of some images alter the meanings of others). The problem, of course, is this: If the mere presence of an image in a comics sequence activates a different sort of ‘reading’ process, then the meaning that the image would have in isolation might have very little to do with the meaning it has within a sequence (any sequence).

All of what I just wrote is a bit sloppy. And I think Neil’s last paragraph identifies the source of some of the sloppiness: Neil’s data (and physiological/psychological data more generally) tell’s us what is going on inside the head/brain. But (as Hilary Putnam was wont to remind us) meanings ain’t necessarily in the head. We should carefully distinguish between the neurological/sensory/whatever processes by which we come to understand the meaning of a bit of text or image, and the meaning of that bit of text or image (which is, depending on one’s philosophical/linguistic views, possibly partially determined by what goes on in the head, but almost certainly not reducible to neurological stuff). And if the question is about meanings in this sense, then we might have a very different story to tell.

I also think Jones point is a really important one, but one about which I don’t have anything particularly insightful to say. I think an interesting related case which might provide some insight here are Molotiu-style abstract comics (which, in my own personal experience, at least, actively resist the sort of unified reading experience described above – I find myself tying to read them, and then noticeably switching to a ‘looking at’ visual mode, and then noticeably switching back to reading mode (or, at least, to a mode where I am attempting to read a narrative into the abstract images) and so on. These are, of course, competently made in the relevant sense, but it seems like they often (intentionally) aim at a phenomenological experience much like the (unintentional) effects of incompetent non-abstract comics.

So, I have two thoughts on Roy’s post. First, I share the intuition that there is a difference between images that are created to belong in a sequence and images that are created to stand alone. I think that there is something fundamentally different about their characteristics. This is often why it is weird when random images are strung together that haven’t been intentionally made to be in a sequence. I haven’t yet run a study on this though.

Second, I’m not sure I believe that there is meaning “outside the brain” and I’d argue fairly vehemently against Putnam’s “semantic externalism” as denial of what we know from cognitive science. I believe all meaning is tied to cognitive structures and is ultimately found within the brain. Language (ahem… and drawing) is a system that has meanings that must be learned, but those constructs are only found in other people’s minds, not floating in the cultural ether. Where are meanings then, if not in people’s brains?

So, I’d press you to say what/where might “meaning outside the brain” be exactly, and how are you tying that to your reading vs. looking distinction.

Neil: With regard to your first point, I agree, but would phrase it differently. I would say that there is a difference between the content of an image when it occurs in a sequence and the content of the image when it stands alone. I don’t think the intentions of the image creator have anything to do with it – after all, an image could be created to stand alone, but later used in a sequence of images (a comic), and that same image would have different contents in the two different contexts (and vice versa). Of course, you are right that when we string together images that weren’t intended to be part of a sequence we often get nonsense (i.e. we often get an instance of Jones’ incompetent comics). But I don’t see any in-principle reason to think that this must be the case – that is, that one couldn’t create a really effective comic out of ‘found’ images. The content of these images would be different in the sequence than the content they had in their intended (stand-alone) contexts, but they might work effectively all the same. In short, I would emphasize the context in which the image occurs, rather than the intentions of the creator of the image.

I do deeply disagree with the second paragraph about meaning. And we don’t need Putnam’s Twin Earth style arguments. Here’s a simple argument: Imagine that all of humanity dies out at time t. Then, years later, at time t*, aliens arrive and their linguists, after much study of the texts that survive, manage to understand our language. If meaning is just cognitive structure in brains (or whatever the alien equivalent of brains turn out to be) then if follows that these texts had no meaning between time t and time t*. And this just seems bizarre – if the texts had no meaning when they were found by the aliens, how on Earth (pun intended) did the aliens learn their meanings?

With regard to meaning, my own views are broadly inferentialist. And I’ll be honest at the outset, I have only thought through these issues in detail for a very specific case – mathematics and logic – I am a logician, not a linguist, by trade, after all! But I do believe something like this holds for all language (and all representations generally, including images). The meaning of an expression (or image, whatever) is constituted (at least in part, and maybe completely) by the patterns of usage for that expression (image, etc.). Patterns, rules, etc. aren’t in the brain – they are in the world, and are as much a part of the world as are physical objects. Of course, we learn the meanings of expressions by detecting these patterns of usage, and hence each person’s understanding of the meaning of an expression might be encoded ‘in the brain’, so to speak. But the meaning itself isn’t – it’s a pattern found outside the brain.

And this allows us to deal with the puzzle in the second paragraph above. Even though all the humans die, and as a result no one is currently engaging in the patterns of usage in question, the texts found by the aliens contain a record of those patterns. Thus, the aliens are able to discover the meanings of expressions in our language because those patterns still exist, and are codified in the texts we leave behind.

Given this, the basic idea behind the reading/looking distinction would come down to this: The patterns of behavior associated with communicating via text (i.e. meanings) are of a different kind than the patterns of behavior associated with communicating via images (i.e. meanings). Now, I don’t have a fully-fleshed-out account of exactly what these patterns are (even for language – that’s a huge, ongoing research project in linguistics and the philosophy of language that has occupied, and will continue to occupy, many very smart people for a very long time). Hence my somewhat wishy-washy talk about how ‘reading’ text, and ‘looking at’ images, feel different in the original post. But I do suspect that there are deep differences here.

From the perspective of this sort of inferentialist account of meaning, one has to be very careful regarding what, exactly, to take from psychological and, in particular, neurological data. It might tell us a whole lot about how we understand meanings (i.e. what goes on in the brain when I come to understand a particular type of expression or image), but such data might have a much more limited role with respect to telling us anything about meanings themselves (just as fMRI readings might tell us a lot about what happens in my brain when I see a friend’s face, versus seeing the face of someone I don’t like, but has little to tell us about my friends). In particular, it seems like your data about images and text being processed in the same regions of the brain, and in similar ways (to oversimplify your comments above and elsewhere) are completely compatible with the meanings of images and the meanings of text being very different sorts of things.

Thanks for the extended clarification Roy. I think that my response to both of your comments boil down to the same thing, which is that I think in both cases we can’t dismiss the role of the brain. In the first case, I emphasize producing images because the content (and form) of images is going to be a byproduct of the cognitive patterns involved in production. One can create a sequence out of “found” images, but I’d hypothesize that it would be deemed less natural than one made to go in sequence.

I also don’t think that your example of aliens really addresses meaning outside the brain at all. If aliens (or us) reconstruct a dead language, then it is then instantiated in their brains. Also, in order to write that in the first place, it had to be produced by someone with patterns in their brains. Plus, aliens would only understand it once they decoded the system so indeed those marks would not have meaning until they become recognized by someone whose brain understand them. The marks only have meaning when there is a brain involved somewhere in the process. (Note also, if its based on writing: the majority of the world’s languages actually have no writing system.)

Also, it makes no sense to me that “patterns of usage” would not be in brains. What then creates, acquires, and transmits the patterns if not brains? (and if your response is “culture” then my reply would be: where is knowledge of culture?) It’s funny you mention the ongoing account within linguistics of recognizing what those patterns are—for the last 60 years linguistics has thought those patterns are in the brain!

For a good alternative to the externalist views of meaning, I recommend Ray Jackendoff’s “A User’s Guide to Thought and Meaning” (which I also happen to have done the illustrations for).

Cognitive science has become increasingly good at investigating meanings themselves too. I agree that just knowing where something happens in the brain (like with fMRI) might not be all that informative. But that’s not the only method that’s used, and studies of semantics have gotten pretty sophisticated, both in cognitive neuroscience and cognitive psychology. They aren’t “solved” problems by any measure, but I think there may be more there than you think.

A decent intro to the sorts of work I’m thinking of might be this lecture by Marta Kutas, who has pioneered much of the study of semantics and the brain: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LicKaWpGj1M

Neil, a few quick comments: I certainly don’t want to dismiss brains. First off, even if meanings aren’t in the brain, the brain will obviously play a very central role in our account of understanding meanings (just like baseball games aren’t in the brain, but the brain plays a huge role in our understanding of, and our playing, baseball).

Now, back to the aliens example. I think we just have a a divergence of theoretical intuitions here. I just find it bizarre to claim that the dead language in question had meaning once, but then stops having meaning (the minute the last speaker dies), and then has meaning again once the aliens reconstruct it. And (not that this is a knock-down consideration) our way of speaking seems to support this intution: it seems more natural, to me, to say, of some expression in a dead language:

“I don’t know what this means.”

rather than:

“I don’t know what this meant.”

In short, although I agree with you that the aliens won’t understand the language until it is decoded. I just disagree that something only has meaning if someone (currently) understands it.

Further, I just don’t think it makes sense to think that patterns of usage ARE in the brain.

Now, to clarify, some parts of these patterns certainly are in the brain (at least, they are if at least some thinking is linguistic).

A pattern of usage for a particular expression is just what it says it is – the pattern in which that expression is used. Expressions are utterances or inscriptions (or thoughts – see previous paragraph) and these are objects outside the brain (again, except for thoughts). Hence patterns of usage are external to the brain.

An analogy: In a certain sense baseball is a particular pattern of actions. A bunch of objects moving around counts as a game of baseball if and only if those objects display the right sort of pattern. (And, perhaps, in addition, if some of those objects – the people – intend to be instantiating those particular patterns. It’s not clear to me that you can ‘accidentally’ play a game of baseball any more than you can ‘accidentally’ use a word correctly.) So the game of baseball is really a certain sort of pattern. Now, brains were certainly involved in identifying or creating this particular pattern (inventing the game), and in transmitting this pattern to other people (teaching them to play the game), and in acquiring knowledge of this pattern (learning to play the game). All of that, however, is consistent with the game of baseball (the pattern in question) being completely outside the brain – it is a pattern (a structure) that exists (is instantiated, loosely speaking) anytime some people are playing a game of baseball.

I would suggest that meanings are relevantly similar to the game of baseball. They are patterns that hold of our actual uses of expressions (or images, etc.) – hence, are (at least some of the time) outside of the brain.

Final note: I probably should have been more careful in my description of inferentialism as a research programme. It certainly is not the majority view in philosophy (I don’t think), although it has been a very prominent and vocal minority within the philosophy of mathematics and logic. With respect to language as a whole it is very much a recent upstart (due most notable to Bob Brandom’s work and its influence), but a very influential one.

Neil:

Also, Jackendoff’s book certainly presents an alternative to externalism (and, viewed in those terms, as an explication of an alternative view, it is really quite a nice book). But the arguments against externalism given in the book are pretty thin and unconvincing, and at times he flat out fails to engage the actual views against which he is supposedly arguing. For a pretty typical reaction (with respect to philosopher who work in this area, at least) to the book, see the Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews review:

https://ndpr.nd.edu/news/33109-a-user-s-guide-to-thought-and-meaning/

With respect to our conversation above, the third-to-last paragraph is particularly relevant.

Yeah, abstract comics are a great example of comics that deliberately resist “reading”. I felt that way about Yokoyama’s Color Engineering from a few years back, found it literally unreadable (and not interesting enough to look at, tbh).

re: semantic inferentialism, that sounds like semantic pragmatism, right? In which case — good god man, that way lies holism, non-compositionality, Jerry Fodor getting upset, cats and dogs living together, etc.

I don’t think we need to identify inferentialism and pragmatism. The inferentialist thinks that meaning is given by rules governing inference (or, on a very broad reading, the rules governing correct use) of the linguistic item in question. So, for example, the meaning of “or” is given by (and exhausted by) the following rules:

(1) If A, then A or B.

(2) If B, then A or B.

(3) If (i) A or B, and (ii) A entails C, and (iii) B entails C, then C.

So an expression * is synonymous with (i.e. has the same meaning as) “or” if and only if it correct usage of * amounts to following rules (1) – (3) with “or” replaced by *.

Nothing pragmatic about that.

[This of course is too simplistic. But hopefully the toy example gives you a flavor of how the view works.]

At any rate, I am not sure I am completely wedded to inferentialism about language as a whole. But I am utterly and completely convinced that inferentialism is the correct account of meaning with respect to basic logical vocabulary like “and”, “not”, “if… then…”, “or”, “for all”, and “there exists”. Further, even for those parts of language where I am not sure about inferentialism, I am convinced that some version of externalism more generally is correct. In short, meanings are something like rules for correct use, or conventions governing use (e.g. David Lewis account in Convention (1969)), or something similar.

Yah, I buy absolutely none of your arguments. But, I can tell that neither one of us is going to convince the other at this point (…isn’t that what empirical evidence is for, garnered by actual science anyhow?), so I’ll just leave it at that.

I will, however, talk more comics if you want.

these are parts of my brain that I’ve got to dredge up from long ago, but…I was thinking of pragmatism as Fodor uses the term for a certain kind of theory of concept-possession, viz. that to have the concept C is to be able to distinguish Cs from non-Cs, and/or make various inferences using C. And it sounds like inferentialism is a version of that? (On the other hand, concept-possession is different from meaning, so I guess you could be inferentialist about the latter but still not a pragmatist about the former?)

(That said, what in god’s name are the alternative semantic theories for logical terms? Inferentialism, as you’ve glossed it, seems so obviously correct that I must be being too dumb to see the other options)

“Also, it makes no sense to me that “patterns of usage” would not be in brains. What then creates, acquires, and transmits the patterns if not brains? (and if your response is “culture” then my reply would be: where is knowledge of culture?) It’s funny you mention the ongoing account within linguistics of recognizing what those patterns are—for the last 60 years linguistics has thought those patterns are in the brain!”

I have trouble with “transmits” part of the statement, and the implied reduction of “culture” to “knowledge of culture.” This elides the materiality of language, and the degree to which the mediums and contexts of transmission inflect meaning. It also obscures the degree to which a culture exists independently of any one “brain,” but is in fact a collectively experienced set of texts and performances that can, and do, affect meaning.

It occurs to me that one might argue that “collective experience” might read as a weasel-phrase for a collection of brains. In a way, I suppose it is. However, I want to stress that the texts, the physicality of spoken language, the role of bodies in space, and a raft of other non-linguistic (and even non-symbolic) factors play into the experience of meaning.

In that last sentence, I meant transmission, not “experience.” (Apologies to Noah for the comment clutter!)

I understand that this discussion is about how the audience processes comics, and not necessarily how people who make comics think about them. However, as someone who followed comics from the sidelines for 30 or so years and just finished my first year at The Center for Cartoon Studies, I have been surprised to learn how little many of my fellow cartoonists separate words and pictures in the making of comics. They are both fully part of the graphic language of comics, and the best cartoonists think about words and pictures as both graphic and narrative wholes. Our brains may well process words and pictures differently, but cartoonists necessarily have to focus on the total effect of the comic. In this way words can not be separated from pictures any more than the rest of the art can be separated from spot blacks. In execution this may not always be the case, but this unification of words and pictures in the service of the comic as a whole more often than not remains the goal.

“Our work using eye-tracking (currently under review) basically shows that similar reading patterns are used between comic panels as across text. There is very little freeform scanning, mostly directed movements, and eye regressions typically move linearly to adjacent images. Eye-movements within images are typically more regularized too, focusing on specific features informative to the sequence (and not scanning details in panels). This is different than what eye-tracking shows for individual images, which are more dispersed and less systematic.”

See, this is a kind of operation in which definition of terms has a particularily clear and active purpose. In this situation I can accept that setting out by defining what comics are has a powerful effect.

Study of a field works best when everything in the sample belongs there (good exclusivity) and when cases are well distributed along any axes that may affect the results of any query which is part of the study (avoid bad exclusivity).

Obviously, selection bias is a constant threat when you ask “what does a subject do in response to object type x?” and you don’t have a strong concept of what does and doesn’t constitute type x.

I can think of comics where the glance jumps about as if from text-block to text-block, and also of comics that invite more exhaustive gazing. It’s a matter of style. One popular approach involves glyphic, part-abstracted drawings to be skim-read, with a low index of content-per-panel – but there are styles around which make different assumptions about the ideal representational and/or narratological capacity of each image, like engaging more mimesis or otherwise ‘telling’ more in each panel. Time is, of course, handled differently in such styles as well. Fully painted comics tend that way, the more landscape there is to look at, the further the distance to be travelled between panels. And now I’m also remembering Jacques Tardi who, not alone among Continental comics artists, allows setting into the storytelling space as an active discursive component. In Tardi’s case this usually happens within a change of mode – for one or two panels we slow down and meander around a street scene replete with architectural detail and optical happenstance before returning to the point-to-point economy of dramatic intrigue. The more roaming-gaze-friendly passages aren’t an exit from comics, just a modulation from the dominant texture.

However, such comics, it is conceivable, could be excluded from an exploration of what comics are like for the reason that they are too different from the typical instance of a definition which has been drawn up for the purpose of deciding which things to explore. That would be an investigation which emerged/extended from a definition, and not an investigation for producing or informing a definition.

Bootstraps, obvs.