The index to the entire Joss Whedon roundtable is here.

_________

The 2002 space Western Firefly is part of a long and grand tradition of Hollywood whitewashing. Although set in the distant future, with no mention of Earth, the show is an almost wholesale transplant of post Civil War American politics, and post WW2, Cold War fantasies about the “Cowboy Era.” The show debuted between waves of renewed enthusiasm for Westerns and doesn’t quite belong to either one: it displays neither Dances With Wolves or Unforgiven’s interest in the politics of justice, nor No Country for Old Men’s interest in the continued relevance of Western themes, tropes, and the genre’s long influence. Instead, Firefly wants to be a grand, apolitical adventure centering on the eternal struggle between authority and rebellion, with the political used for colour; a true throwback. But buried history doesn’t stay buried, and Firefly’s attempt to neutralize American history and reuse it as space history only makes its problematic racial politics the more obvious.

Firefly is set in a future star empire whose ruling class is culturally descended from white America and a still Han-dominated China. As the empire stretched across solar systems, pioneers set out into the stars, ahead of the empire’s armed forces and commercial powers, to settle in new systems and go their own way. The powerful Core worlds thrive on surveillance and control and settlers hoped to escape this. But naturally, as they proved their settlements, representatives of the Core followed, chasing tax revenue, valuable exports, and the expansion of their influence. Taxation without representation, economic domination by distant powers, and finally, rebellion by new non-Core powers, including a new merchant class and farmers alike. This is the recent past of Firefly: the show focuses on former Alliance rebels, now turned grifters, and their attempts to carve out a life in a period of post-war reconstruction.

They face ne’er do wells, Core military and police forces, vexatious local authorities, constantly failing equipment, and Reavers, the wild frontier cannibals who roam deep space and less-monitored shipping lanes in search of victims. The meta story of Firefly, both its core cast and the universe as a whole, is based on American Reconstruction literature and Westerns; the story of Alliance rebels is the story of Southern “rebels,” and the show’s creators have gone on record saying that the goal of Firefly was to write a Reconstruction Western absent the racism. The Chinese ancestry of this empire is used only for colour: there are no Asian characters in the core cast and non-black people of colour appear only sparingly as supporting characters. And although there are two black people in the core cast — second in command Zoe and mysterious Preacher Book — black people too are seldom seen in the backgrounds of daily life in the Core and Rebel worlds. The evidence of Firefly’s origin — as post-racial Western fantasy about race — lingers and its attempts at distance only emphasize the political: what does it mean to take race out of racist history and offer it up as neutral entertainment built around timeless values of freedom and exploration?

Westerns are primarily concerned with a tight cluster of themes: the frontier, the march of civilization, whiteness and otherness, manliness, self-reliance, and survival. The genre is diverse but these themes are common to most forms. Conservative Westerns pit underdog colonizers against the expansion of industrial civilization and against the native peoples they must wipe out. So-called dirty Westerns often pit misfits, cowboys, and criminals against placid colonizers, and often feature people of colour as sidekicks, co-travellers, or even heroes. Latter days critical Westerns more readily acknowledge the complicated and interconnected relationships of oppression that built The West, and more naturally bring women and people of colour to the fore. But even the Westerns of 2015 can’t sidestep race or racist history–of America and of the genre itself. Firefly, though, tries to do just that.

As a Reconstruction, conservative Western, Firefly draws on those early stories of colonizers fleeing technocratic civilization and meeting mysterious villains, deep in unmapped territory: namely, Native Americans. On Firefly, those “frontier” raiders are the Reavers, intended to be racially neutral. The show wants to use the racist trope of savage, Indian raiders, harassing wagon trains, and burning homesteads, while ejecting the racial element. “De-racialization” is achieved through blind casting and not calling the Reavers “natives.” Reavers are an ever-present threat to this new, more free civilization, who mutilate themselves and their victims – whom they also consume – an act that recalls fears of being “scalped” by Apaches. They are mindlessly violent, speak only in grunts and growls, and are beyond the reach of civilizing forces, Core and Rebel alike. They are the other who lurks in the dark spaces beyond the horizon, who can’t be reasoned with. In short, racism is denied, but not eliminated.

It’s eventually revealed in Serenity that Reavers aren’t natural to deep space, but manufactured: a product of pharmaceutical experimentation and institutional violence. Finding their authority threatened, Core powers ordered dissent on distant colony world Miranda to be put down. The solution of local representatives was to attempt to write out aggression and independence through some science fiction chemical treatment. The result was near genocidal, with 99% of the population wiped out and 1%, the most aggressive, weaponized in a permanent, cannibalistic psychosis. Vast swathes of valuable space and planets have since been written off as Reaver territory, space where they can run wild without threatening the good people of the Core worlds, and Rebel worlds that have been brought back into the fold. This is, effectively, a reservation for monsters. Reavers venture out of their territory sometimes in search of all-Rebel victims, and this serves as evidence of the importance of Core authorities, the only group powerful enough to meaningfully resist them. The Core, of course, has no interest in a permanent solution: Reaver rage, a symptom of Core violence, is expended on innocent homesteaders, who just happened to be in their way. Reavers are convenient for Core power, a deterrent to future rebellion that requires no upkeep or compensation, an ever-present argument for the expansion of Core control.

Side by side with obvious frontier themes are Firefly‘s debts to the American War of Independence and Civil War. Slavery is absent and economics is only shallowly depicted, so it’s difficult to tease out the political differences between Core and pioneer powers; freedom and representation are the key issues cited for why the rebellion began, but both camps have an essentially colonizing ideology – they seek to find new world-territories to “settle” and “civilize” and exploit as they wish. The theme song explains that “Earth was used up so we lit on out,” which recalls Huck Finn’s decision to head for the territories and avoid the cruel rules of “civilized” society.

In Firefly this rejection of society isn’t political, but a vague distaste for the fancy folk of the Core. Neither camp expresses a clear political philosophy outside of “domination” and “freedom” and “expansion.” It is in the interests of both that as their power and territory expands, the Reavers are pushed ever outwards. Rebels desire freedom, but for whom? In constructing the Rebels greatest challenge in taming the space frontier, the Reavers, Firefly’s showrunners neatly sidestepped the issue of colonialism. Because they are “monsters” there is no need for the crew of the Serenity to regret killing Reavers by the bushel; there is no need for settlers to regret moving into Reaver territory and “civilizing” it. With no clear political or cultural distinction between the two camps, the settlers act as unknowing vanguard of the technocratic Core worlds — it’s all of a piece, this unchallenged white, settler-colonial expansion into the stars. Manifest space destiny.

This is a wholesale transplantation of Spaghetti Western politics, with Native American myth-ghosts — rarely fully embodied and realized in Westerns; more often appearing as representations of the savage Other — made into monstrous space cannibals. Consider: conservative Westerns don’t deal with the obvious politics of slavery, indentured Asian workers, or the ecological consequences of frontierism. They engage political questions solely through the rubric of simple, personal freedom: here is a man, going his own way.

Captain Mal Reynolds (Nathan Fillion), Firefly’s lead character and captain of the show’s ragtag band of pirates and misfits, is quite a typical Western hero. He is by turns sullen and snarky, he has a dark, traumatizing past, he has an enduring grudge against those who would tell him what to do, and while he prefers to work alone, he has heart to spare for women in distress and trusted comrades. But he offers no alternative ideology or principle around which to build a community, and is an authority unto himself thanks to his military prowess and force of personality.

Mal’s authority is challenged through moments of buffoonery and moral failing, but ultimately left unthreatened, and in super-waif River Tam, a Core refugee, he finds a purpose. The close of Serenity, Firefly’s big screen wrap up, sees Mal vowing a kind of permanent rebellion alongside River, revealed to be, like the Reavers, a victim of Core experimentation. Mal and River are meant to be destabilizing, unconquerable figures – an ever-present challenge to settled authority. Their charm is mainly in their independent thought; their need to go their own way. But their challenge is insubstantial; their rallying cry merely, don’t go too far.

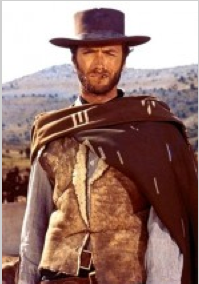

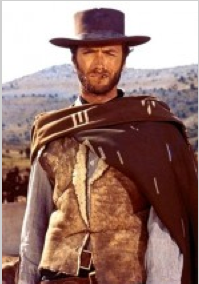

This indulgence in the tropes and visual signifiers of the Western genre was common to early, more conservative Westerns and to children’s Westerns; while Dirty Westerns and the films of the contemporary Western resurgence pack in the visual signifiers just as heavily, they problematize tropes like the mysterious wandering gunfighter and the grizzled sheriff. The aims of these films are varied but what they have in common is discomfort and unrest; the sense of things not being settled or sure. The archetypal Dirty Western anti-hero, Clint Eastwood’s Man With No Name, isn’t a good man, but he’s generally a just one, and he moves through the West with purpose.

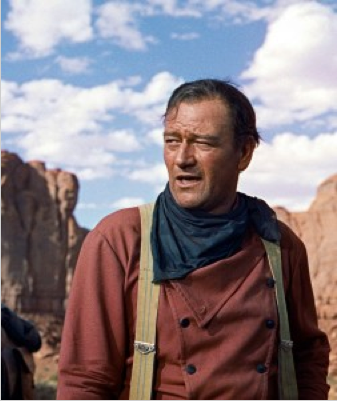

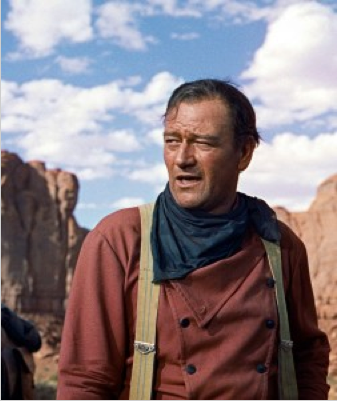

The Man isn’t Eastwood’s only Western role — he started out in simpler, cheerier fare. Like Eastwood, John Wayne’s career followed the development of the genre that made him popular. Though he started out playing untroubled (and sometimes singing) cowboys, his roles, like the films he starred in, got more complex with time. In The Searchers he played a complicated Confederate veteran searching for his kidnapped niece. Like Mal, Ethan’s antagonists are authority and “savages,” in his case Comanche warriors. He resists them with equal fervour, no mercy for either.

To be frank, Ethan is a terrible person. He kills people who get in his way, mutilates the bodies of his enemies, and would rather see his niece die than live with the Comanches. Mal’s character and Nathan Fillion’s performance borrow liberally from the Man With No Name and Ethan: Mal’s famous clothing, even down to colouring, bears striking resemblance to Ethan’s; the physicality of Fillion’s performance, posture, gesture and expression, combines the Man With No Name’s untouchability with Ethan’s intensity. To say that Mal is a melting pot of Western archetypes and tropes is too much: Wayne and Eastwood are two of the most famous Western stars. Ethan and the Man are still studied and talked about and, dare I say it, iconic. This is, in miniature, how Firefly borrows from and neutralizes Westerns of the past. Clothe Mal in Ethan’s shirt and give him the Man’s stance, let him share Ethan’s background and so many of the Man’s mannerisms — but do so without Ethan’s monstrosity or the Man’s coldness.

But this is not necessary for contemporary Westerns. Is a Western just a collection of funny clothes and tropes? The genre is inseparable from the time it aims to portray. Transplants of the Western genre into different times, places, and modes work best when they recreate some of the political tensions that drove Westward expansion and the national interest that still fuels fantasies of the frontier. Updates to the genre work best when they acknowledge and critically engage with the subject matter

The 2012 Western revenge fantasy, Django Unchained, centres on a similarly charismatic rebel, but unlike Mal, Django (Jamie Foxx) has clear purpose to match the power of his personality. Narrowly speaking, freed slave turned bounty hunter Django’s purpose is to find and rescue his wife Broomhilda, but broadly speaking, his goal is more radical: freedom for him and his people and the complete destruction of settler colonialism. Like Mal and most other Western leads, Django isn’t an ideologue or political activist; this broader goal isn’t expressed to us through speeches or organizing. Rather, it’s written into the very fabric of the character: from his posture, to his actions, to his speech. His existence and his humanity in and of themselves are challenges to American settler-colonialism; his continued and disruptive participation in polite, Southern society, though a ruse, is discomfitting too. Workers in the slave economy are disturbed by his confidence, self-possession, and competence. This is the shaky illogic on which the slave economy is built: complete denial of the humanity of slaves and all black people in America is necessary and must constantly be renewed and reified. Evidence of black humanity is disturbing. Evidence of black competence must be explained or absorbed into the slave economy. But here is Django, gun in hand, ready for anything. This is an image that cannot be absorbed; it must be destroyed.

Like Mal, Django lives on the fringes of society (as all black people did in the slave-holding South). Also like Mal, much of Django’s dress and character are informed by Westerns that came before. But for Django, the consequences of rebellions minor and major are quite different. He’s clothed like any number of cowboy rebels and he stands like the Man, but Django isn’t a settler or an ex-Confederate. He’s not a rebel in search of a purpose, but is a man born to rebel against the racist logic of his society.

At the end of the film, he rides off into the sunset with Broomhilda. But we know that Django and Broomhilda will never be safe so long as the settler-colonial regime remains. It’s not only Django’s actions through the course of the film — freeing his wife and killing a major slave-owner and his employees — or his personality that make him a target, it’s his very existence as a free black man. Not even in the North, where slavery is no longer the engine of the American economy, would he and Broomhilda be safe: they will never have white privilege.

Let’s consider another modern Western, one where the lead has more purely personal motive, and is on more even stakes with Mal. The moral imperative in 1992’s Unforgiven is not on William Munny’s side. Or at least it’s not on the side of making your living off of violence. Munny (Clint Eastwood again) is a retired bandit. He made his stake off of violence and theft, then retired to marry and raise children and farm. He’s drawn back into a life of violence by old friend Ned Logan (Morgan Freeman), who seeks his help in pursuing a large bounty. Two cowboys cheated and then disfigured a sex worker, and now her co-workers have put together a large pot for their heads. Complicating things is the local sheriff, who doesn’t allow vigilantism (or banditry) and is himself an imperfect embodiment of the law — but he tries. Munny and Logan need the money — Munny’s family is sick — and the sex workers deserve justice, but the sheriff is right that vigilantism and the breakdown of social order results in widespread and indiscriminate suffering. Munny and Logan’s rebellion, their unwillingness to bow to coercive settler authority, though, has merit too. That authority does not bring justice, whether economic, social, or legal; it too often protects the status quo even when that status quo requires great suffering. It’s the sheriff who gets the plot moving: his inadequate, unsatisfying judgement against the cowboys leaves the brothel workers feeling scorned.

Like Django, the brothel workers have some moral authority behind their demands for revenge. They have been done wrong and the status quo can only continue to do them wrong. And while Munny’s more or less comfortable retirement was a privilege of his whiteness and maleness, Ned Logan doesn’t have the same luck. As a black man, his retirement can only be more precarious; his freedoms to own property, love, move, and participate in society (polite or otherwise) are limited. Ned Logan will never be truly safe in this world — he cannot simply put down stakes and join the settler class. Glad submission to the sheriff’s justice is not possible for the brothel workers or for Ned, only submission by necessity, for safety.

Also important in Unforgiven are age and time. Munny, Logan and the sheriff are old. They’ve been doing this for some time, either rebelling against or maintaining the social order. The film is set in 1881, near the close of the frontier/settlement era, and the start of our time, the hyper-industrialized, globalized now. They are all aging out of their roles and out of their purposes — they are watching the end of their relevance to the world and the establishment of a new social order. Munny, of course, is played by Clint Eastwood, whose career was built on an older breed of Western. It’s interesting and ironic to see him come to this. Ultimately, Unforgiven is about consequences and endings — the collapse of the Western fantasy. Django Unchained’s ending, Django flirtatiously showing of his horsemanship for Broomhilda (Kerry Washington), the couple escaping into an unbounded future, is of a more fantastical mode, but Django leaves the Western reconstituted; the Western hero reborn. Perhaps Munny is what happens when a Man With No Name takes one on and settles down, but he is not what happens when a Mal Reynolds finds his purpose: Firefly aims for the Western fantasy unquestioned and eternal.

Firefly and Serenity come down not on the side of revolution or transformation, but on the side of mischief. What is the fundamental challenge of the rebels or of the crew of the Serenity? That remains unclear. “I aim to misbehave,” is Mal’s best known catchphrase and the underlying drive of the crew — they are misfits and so they cannot conform; they are misfits and so they must rebel. And although this rebellion results in losses, both during the Rebellion proper and during the course of Serenity, there is no best before date set on their travels. It’s space, after all; there will always be a further frontier to flee to.

Firefly revels in this, seeking an adventure marked by timelessness; a Western romp without modernization to contend with; without thorny questions of displacement, racial exploitation, and nation building. What does Firefly have to say about power and authority? About the ethics of settlement? Mainly: that individual freedom should be maximized and that while the formal power of government is vast and usually corrupt, it’s not institutionalized in culture. That is, Firefly does not in any meaningful way engage with systems of power and inequality; rather, it obscures their existence in favour of a neutralized and eternal frontier. The darkness at the heart of this universe is not cultural, it’s merely government overreach and abuse; the Rebels are in no way complicit and their push for freedom is pure-hearted.

While other contemporary Westerns touch on the complex network of violence, power, and injustice that lies at the root of nation-building and frontier-settling — with varying levels of engagement and success — Firefly boils this down to one relationship: rebellion and authority. What is a frontier in Firefly? Merely space to breathe, to put down roots, to take whole worlds and make them your own. Destiny. What is oppression? Merely taxation without representation.

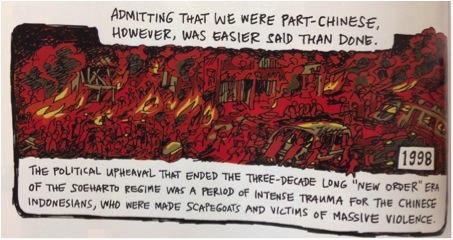

But Firefly’s attempt at sidestepping racial politics of Westerns and American history only make them more apparent: societies manufacture internal Others and underclasses — are Rebel and pirate really as low as it goes? The very absence of the dispossessed in so many Westerns, the wholesale erasure of Black and Chinese workers, of Native Americans either pushed onto reserves or protecting what land they have left, makes their propagandistic motives more apparent. Warm-hearted, adventurous Westerns work to reinforce the fiction of an America won by grit and gumption, not colonization, enslavement, and genocide. Firefly’s discomfort with these truths, its awkward reach toward post-racial fantasy, only serves to reinvigorate these racist fantasies: in the future American melting pot of Firefly, all cultural disjunctures, all power imbalances and dirty history have been melted away. But the melting is inexpert and ultimately unsuccessful: Firefly’s attempt at de-racialization and de-contextualization cannot succeed. The context and the history remain, never fully buried.