The index to the entire Joss Whedon roundtable is here.

_________

In the Joss Whedon Avengers universe, to exist somewhere outside of the gender binary is suspect; to be genderless is monstrous.

Whedon adores the “superheroes can be dangerous” theme. In both Avengers films, the Avengers’ potential danger to society is presented repeatedly. Superpowers, whether innate, learned, or built, are dangerous, and superpowers without proper control are likened to nuclear weapons in the hands of madmen. The control of superpowers is associated with the command and control of gender expression. While the 2012 Avengers film features only one female Avenger, Black Widow, the recent Avengers: Age of Ultron introduces additional team members, revealing a sharp gender distinction.

Summarized by Agent Maria Hill – he’s fast and she’s weird – twin siblings Scarlet Witch and Quicksilver are the representative binary in the Whedon Avengers universe. Quicksilver’s superpower is speed: simple, mono-dimensional, active. There is no further revelation or exploration of his powers throughout the course of the film. Scarlet Witch’s power is weird: manipulative, subversive, unpredictable. Wielding sparks of scarlet lightening from her fingertips, she exhibits the ability to control both objects and minds. Her exact powers are never defined, but we learn that she can control the emotions of others and that her own strong emotions activate her most destructive powers. The twins are a traditional gender dichotomy; he is bodily action and she emotional manipulation. Both expressions are conceived of as equally powerful – the difference lies in the approach. Theirs is the traditional superhero’s fate: he meets a hero’s death and she rounds out a heroic team. Channeled in traditionally masculine or feminine ways, superpowers are safe and effective.

In the Whedon Avengers Universe, both exaggerated and mutilated gender is dangerous, whether it’s the inflated maleness of the Hulk or the broken femaleness of Black Widow. Bruce Banner’s angry transformations to the muscular and furious Hulk are an easy metaphor for the worst of the testosterone-fueled violence of masculinity. Banner, who fears and reviles “the other guy,” rejects this aspect of himself as a monster. His über-gender has rendered him incapable of raising a traditional family with the would-be mother of his children, Black Widow, alter ego Natasha Romanov. Romanov herself is played up as overly flirtatious, not to be trusted, and duplicitous. Romanov assures Banner, however, that her indoctrination as an assassin in the Red Room included a traumatic forced sterilization. After the confession of his inability to provide her the stable family life that she (supposedly) desires, she confesses her dark secret of infertility and wonders “who’s the monstrous one now?”

If femininity is emotional power – the power to exploit our attachments to one another, as Scarlet Witch does – then to harm that power hampers the overall humanity of the female person. A woman without the ability to form that most intimate of biological relationships must be lacking her power. A man whose gender is hyper-expressive is (quite literally in the case of Hulk) not fully human either. He lacks the ability to control his power.

Both Hulk and Black Widow are the only superheroes who, once having joined the Avengers, express doubt over their continued ability to play the part of “good guy”. Banner is prone to brooding and insisting that he is simply too dangerous for human interaction or vehicular containment. Romanov expresses her “dream” to actually be an Avenger, even though she is clearly an established member of the group and hardly the only Avenger lacking superhuman powers. With their gender expressions out of whack, Hulk and Black Widow at best can be marginalized members of the team, capable of doing good, but perhaps not to be fully trusted.

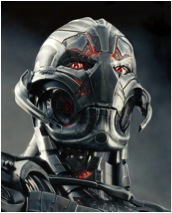

If hyper- or mutilated-gender is dangerous, a lack of gender expression is nothing short of monstrous. The most terrifying monster is, of course, that which exhibits an apparently human mind but is somehow less than human. Ultron, who is human intelligence and emotion trapped inside a crumbling, mechanical body, is humanity without physical expression. It has no gendered body – and therefore no power – with which to control the worst aspects of humanity. In a confrontation scene in which Ulysses Klaue dismisses Scarlet Witch and asks to speak instead to the man in charge, Ultron aborts the interrogation and declares: “there is no man in charge.”

The irony is that Ultron is logically the “man” in charge. The character is voiced by male actor James Spader, and we as an audience have a tendency to presume that anthropomorphized non-humans (dogs, toasters, robots, what-have-you) have a default gender of male. Thus, given the presumption of Ultron’s “maleness”, such a statement might normally be interpreted to suggest Ultron’s lack of humanity – i.e., Ultron is a machine, not a human, and therefore there is no (hu)man in charge. However, the juxtaposition of the specificity of the word “man” with Scarlet Witch’s abrupt and sexist dismissal allows for a second interpretation: Ultron denies not only humanity, but with it gender altogether. There is no “man in charge” because a robot is in charge, and, well, machines have no gender.

Vision is the logical counterpoint to Ultron. With a mind similarly born of Tony Stark’s foray into artificial intelligence, but with a human body grown by medical genius Dr. Helen Cho, Vision is Ultron’s foil. Vision is, to be sure, ambiguous, and the ambiguity remains at the end of the film. The character, however, is clearly intended to be Good, and his Goodness is grounded in his full association with humanity, which includes an apparently male gender (indeed, a hetero-normative male gender, as the beginnings of his relationship with Scarlet Witch implies).

In the Whedon Avengers universe, a tightly defined gender binary informs the superhero’s ability to be human, and therefore to be good. Shambolic gender expression limits the superhero’s humanity, resulting in an ambiguous, potentially dangerous figure. To remove gender expression from the equation altogether stumbles upon an uncanny valley in which the human-esque but grotesque terrify and repulse.

—-

Em Liu is a fiction enthusiast particularly interested in depictions of women and minorities onscreen. She blogs over at FictionDiversity.com, and you can follow her on Twitter at @OLiu1230

I realize this is part of a roundtable on Whedon, but I would have preferred if you used the term “in the Avengers movies” instead of attributing credit to Whedon for other people’s work with the phrase “Whedon Avengers universe”.

He didn’t create virtually any of the characters in the film and the gender expression of Scarlet Witch, Quicksilver and Hulk is mostly from the source material.

Hi Pallas – the term “Joss Whedon Avengers universe” emphasizes that I am discussing the Avengers films as directed by Joss Whedon, as opposed to any other presentation of the Avengers. I recognize that Whedon is not responsible for the creation of the Avengers.

“the gender expression of Scarlet Witch, Quicksilver and Hulk is mostly from the source material.”

I don’t know about that. Scarlet Witch’s powers and personality have varied quite a bit over the years, if I remember correctly—as have the Hulk’s, for that matter. And certainly the stuff about Black Widow’s sterilization isn’t canon that I remember.

Whedon’s the director of the films. I’m sure he has corporate and fan dictats to negotiate, but, you know, to make up for that, he’s had literally truckloads of money dumped into his bank account.

I was also struck by the adherence to a strict gender binary in *The Avengers*–what with all the brouhaha, I was thinking more about Black Widow’s arc, but I think you’re absolutely right to pair it with Scarlet Witch. Motherhood, emotions–they’re all part of the CRAZY PERIOD POWER that defines women, right?

This preoccupation with out-of-control and mysterious feminine power is a thread through all of Whedon’s work, I think (and while he didn’t create The Avengers, it might help explain which parts of the mythology end up getting explored). He seems super-preoccupied with the classic horror trope of women as conduits for some kind of intense but impossible-to-comprehend power. The interesting thing is that these women become the protagonist instead of the threat, but this essentializing understanding of feminine power remains. It’s clearest in his representations of motherhood, I think (did anyone but me see that terrible episode of Dollhouse, for instance?).

Although maybe Joyce from Buffy is a counter-example, since she’s so checked out…

Anyway–usually I find this kind of second-wave thread more charming than frustrating in Whedon’s work. It’s old-fashioned, but I like how he generally allows enough room for character development to undo the essential depictions of gender. And it’s important to consider that Buffy herself is a potential counter-argument here–her powers are very much within the masculine framework you lay out here (super-strength, speed, agility, etc.). Lots of cool stuff to think about here, thanks!

“vehicular containment”?

@Anne – I agree completely. The “crazy period power” (awesome phrase btw) is a bit trite, but ultimately Whedon seems to be saying that men and women are true equals; they just approach things differently. Which is nice, I guess. It just doesn’t leave room for different expressions of gender outside of a binary.

@Graham – a joking reference to the numerous concerns raised in the film about Banner being trapped in the SHIELD helicarrier.

You can’t actually give Whedon credit for his accomplishment unless you compare his take to the source material to see what is Whedon and what is not Whedon. Otherwise you’re just doing a reading of a movie you watched which happens to be an adaptation of some other thing.

I can, and I did ;)

I wasn’t actually interested in drawing comparisons between the films and the source material, or even in examining Whedon’s contributions per se. I was interested in doing a film analysis on Whedon’s Avengers films, and a film analysis need only analyze the work itself.

“a film analysis need only analyze the work itself.”

I completely agree.

My own reading of the Hulk / Black Widow situation would rather be that they were both forced by outside forces into their respective gendered stereotypes of muscular brute and femme fatale. They’re not the only walking stereotypes in the movie, but they’re the two who realise it which makes their relationship plausible and their characters more interesting.

I know I’m a very generous reader, though, and you point out some interesting stuff regarding Ultron, Scarlett Witch and Quicksilver.

And as a friend pointed out, Hawkeye’s power in the movie seems to be hyper heterosexuality. It’s interesting that the heart of the movie (and the scene for which Whedon fought the studio most, aparently) is a farm in the middle of nowhere, where Hawkeye is revealed to be a typical family guy. And suddenly, without any prior indication in this movie or the ones before, there’s talk about Hawkeye being the one that keeps the team sticking together. That’s a fairly traditional set of values there.

Hawkeye is also a father figure to Quicksivler and Scarlet Witch. I’m not sure if that’s about heterosexuality as much as masculinity though.

The “we’re really fighting for the nuclear family on a farm” thread in Age of Ultron is pretty repulsive, imo.

Sort of more reason to wish that Ultron had killed them all. Oh well…

Ahaha Noah I had the same reaction to the Hawkeye sob- (sorry, back-) story. The film was also clearly presenting Hawkeye and his wife as a foil to the Bruce/Natasha match, so I didn’t feel a particular urge to recycle that one in this piece.

Cedric, you bring up some interesting points. I thought your interpretation of Hawkeye as “hyper heterosexual” was especially surprising, given that I read him as “hyper hetero-normative”, or just “masculine” as pallas pointed out. I.e., he’s a badass superhero (sort of) but deep down, he’s just a nice, normal guy who lives on a farm with a wife and three kids.

Yeah heteronormative is more what I meant. Poor choice of word on my part. He’s probably the least sexual character now that I think of it.

The Hawkeye farm scene seems blatantly reminiscent of John Ford and/or WWII films such as “They Were Expendable.” One of Ford’s sets was an American front porch in the Philippines, in the middle of a war, with John Wayne sweetly romancing Donna Reed on the porch swing. Ford had seen action and undoubtedly knew the porch to be ridiculous, but it was a common “show the audience what we’re fighting for” moment.

It’s so common, I figured it must have been an homage of some sort. The Avengers movies follow a template similar to that of WWII films, as well as later war movies.

Sorry for veering off the analysis of “the film alone!”

“The Hawkeye farm scene seems blatantly reminiscent of John Ford and/or WWII films such as “They Were Expendable.”

Maybe but the “superheroes flee to the shelter of an isolated farm” thing was done in the 1990 Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles film. While at the farm they all have a spirit vision of their father, Splinter, and that helps them come together as a family to fight Shredder and his evil ninjas.

Similarly father figure Nick Fury shows up at the farm for a pep talk.

@ Autumn

That’s the most promising explanation I’ve heard yet for that weird scene.

When the first Avengers film was in theaters, Eileen Jones, the world’s greatest movie reviewer, pegged it as an exercise in World War II/Greatest Generation nostalgia – with Generation X skepticism represented in Tony Stark, only to be rejected – and of course that’s since metastasized into Agent Carter. (http://exiledonline.com/the-avengers-its-yknow-for-kids/)

At the time I assumed the slant was just a result of going along with the clichés of the genre. But maybe it was actually something personal to Joss Whedon all along.

Actually, the first thing I thought of when I saw the safe house was the farm house from The Walking Dead…looks very similar from the outside.

Pingback: Avenging the Avengers | Fiction Diversity

I loved the farm sequence. Like they dropped down the rabbit-hole out of Superland and into a heightened “normality”. Like the Avengers taking a detox spa retreat.

Hawkeye’s having a rural nuclear family is actually subversive in superhero genre terms.

On another note– Noah somewhere wrote an interesting article about Ultron leading a slave uprising, sort of an electronic Nat Turner. I think Whedon was very much aware of this analogy, as shown in Ultron’s bitter lament: ‘Stark wanted a savior, and he created a slave!’

When you get down to it, Stark is the villain of the film.

Well the slave analogy, if intended, is very badly intended. I don’t remember a slave uprising leading into something like Ultron’s attempt to kill all humanity.

OOps, I meant “very badly handled”

My piece on Ultron and the slavery metaphor is here.