Quentin Tarantino implicates the viewer in onscreen violence, while also delivering standard genre pleasures. You laugh as people are shot, and you also laugh as people are shot. The audience feels superior to the rush of violence, while participating in it.

This seems like a standard criticism of Tarantino; I’ve had people make it in discussions with me several times this week. But, I have to say, it doesn’t make a lot of sense. Tarantino is very interested in genre pleasures, obviously, and sometimes he delivers on them. But just as often he interrupts them, or refuses to follow through. He really isn’t Paul Verhoeven, who will show you Sharon Stone’s crotch while sneering at you for looking at Sharon Stone’s crotch. Tarantino is almost always doing something more complicated.

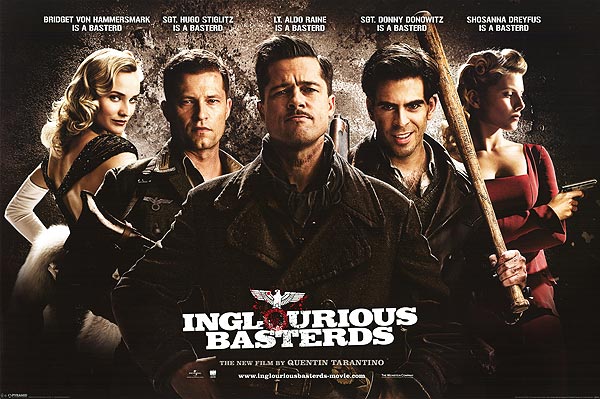

I could use any Tarantino film as an example, I think, but since I just saw Inglorious Basterds, we’ll go with that. This is a war film, obviously. When Verhoeven shot a war film, Starship Troopers, he hit all the marks of the war film — battles, crusty sergeants, bravery, visceral victory— while suggesting off to the side that the humans were in fact that evil bad guys killing the aliens. You get your critique of genre pleasures, but you also get genre pleasures. That’s the Verhoeven way.

It’s not the Tarantino way, though. There aren’t any pitched battles at all in Inglorious Basterds. Nor as a result are there standard moments of bravery in battle—unless you count the Nazi war hero Zoller’s filmed recreation of his own fight killing the good guys. There are certainly brave people in the film on the Allied side; one of them gets ignominiously choked to death; another gets shot because he can’t do a German accent right; a third dies before she can see her revenge enacted; several others show their bravery by killing a roomful of unarmed civilians. The person who saves the world and ends the war is a Nazi traitor motivated purely by greed and self-interest. The big name star, Brad Pitt, does basically nothing throughout the film except speak in a ridiculous Appalachian accent and torture people.

Other Tarantino films make a few more concessions to genre; Kill Bill 1, especially. But Tarantino is always taking genre apart in ways that render it nonfunctional. The big final shoot out in Pulp Fiction never happens; you never see the heist in Reservoir Dogs; the hero refuses to ride off into the sunset with the heroine in Jackie Brown. Kill Bill 2 ends with an hour of nattering talk. Which I think is kind of a crappy, boring conclusion. But a big part of the way it’s crappy and boring is that it doesn’t fulfill genre conventions.

And I suspect that that’s why other people react to Tarantino with such visceral dislike, when they do react to him with visceral dislike. His relationship to genre is frustrating. He uses genre markers, and sets up situations where you expect genre pleasures, but then he refuses to follow through. You could argue that that makes him too clever by half. But I don’t think you can really argue that, in Inglorious Basterds, he’s giving the audience what they want (unless, of course, what they want is to be frustrated.)

Really not missing any of the genre payoffs in Tarantino’s films as you suggest, that actually makes his films more interesting … My issue with his typical films is they’re more about Tarantino and the audience ‘getting it’ than the characters that actually are in the film (Basterds is a different case though). At the same time I can appreciate his method, because even if Pulp Fiction is mostly Tarantino rambling on about his obsessions, his ‘deconstruction’ of genre was a totally new thing back then, is still really entertaining and probably helped to further damage the problematic separation of high and low art.

PS you may have noticed before I’m not a native speaker so please excuse my sloppy English.

The problem I have with your take on Pulp Fiction in that other thread- where you said it doesn’t deliver the genre expectations- is that one of the biggest crime shows in the modern era, The Sopranos, has the same style. (Sometimes you get a shootout, but often you just get a mob boss moping around and talking to his shrink, the ending episode was an exercise in frustrating the audience in that final scene)

Maybe that’s a result of Tarantino’s influence but it sort of puts him in the center of genre expectations when the biggest show in the genre had this style.

Also Jackie Brown is an adaptation of a book by a prolific crime writer, so your argument that “the hero refuses to ride off into the sunset with the heroine in Jackie Brown” is somehow outside the norm for the genre seems unproven.

Does the hero really usually get together with the heroine in crime fiction? I feel like in a noir-ish story that would be unlikely.

I don’t think The Sopranos is the same style as Pulp Fiction at all. To begin with, unlike Pulp Fiction, The Sopranos has no idea how silly it is. More fundamentally, The Sopranos always says “This is a gangster story done as serious art, unlike all those other, compromised gangster stories,” while Pulp Fiction is sometimes simply genre entertainment, not claiming to please you in any way besides the way in which good genre entertainment always done, and sometimes becomes something else.

Come to think of it, maybe that’s a significant part of what a lot of people hate about Tarantino: In an era when people are highly invested in the notion that the trash they enjoy is as deep as Shakespeare – and such as Joss Whedon, David Chase, Christopher Nolan, George R. R. Martin and his amenueses at HBO, and so on are on hand to tell them they’re right – Tarantino makes movies that are clearly pretty smart, and clearly love trash, but have no interest in pretending that trash is anything but trash.

So, you know Tarantino changed the ending in Jackie Brown, right? In the book, the hero and heroine ride into the sunset.

The book isn’t very good. The film is much, much better.

Again, I really love Tarantino’s characters. He cares much, much more about them than is usual in genre entertainment. It’s hard for me to believe that’s even in question.

“Jackie Brown is an adaptation of a book by a prolific crime”

Tarantino also changed the race of the main character, an alteration which matters a great deal for the film, and for genre expectations. Basically everything good about the movie comes from Tarantino refusing to follow through on the book’s pretty boring blueprint.

haha funny thing is i do believe The Sopranos is as deep as Shakespeare! But I agree it isnt like Pulp Fiction at all, for different reasons … I would say there is an evolution of postmodern genre from Robocop (false naivety) to Pulp Fiction (emphatic irony) to The Sopranos (depression).

I didn’t know about the changed ending from the Jackie Brown source material.

Graham you wrote:

“Tarantino makes movies that are clearly pretty smart, and clearly love trash, but have no interest in pretending that trash is anything but trash.”

If you mean that his movies are intended to be perceived as trash, I’m not convinced. When Tarantino doesn’t show the Heist in Reservoir Dogs or has the glowing briefcase thing, isn’t that sort of a claim on his part that his films are “art” not just trash? How about the ironic presentation of a definition of “Pulp Fiction” in the opening of the movie, as if to prep you to feel like there’s an element of ironic distance from the source material as if he is perhaps above it on some level?

How about the long dialogue bits about pop culture that break the “rules” of screenwriting?

Or when he does all the scenes out or order, non-linear like? Aren’t those claims on his part that his movies are “art”?

That said perhaps as he keeps making more and more films his style feels more like trashy fun that “art”.

“You laugh as people are shot, and you also laugh as people are shot.”

I think this is a typo.

Nope; says what I wanted to say.

@ Noah

It was a great sentence.

@ pallas

What I said is that his films sometimes simply work the way that good genre entertainment does, and sometimes they do something else. You’ve listed examples of the latter, but there’s also a lot – say, Jules delivering a Biblical quote that actually isn’t before massacring the slackers, or his wallet reading “Bad Motherfucker” – that could just as well be in a pure genre film; and unlike HBO, there’s no subtext to those parts saying “This too is serious art.”

This essay has forced me to rethink my distaste for Inglourious Basterds. But I will say showing the cool macho soldiers torture Nazis is giving audiences what they want, particularly the last shot of Brad Pitt disfiguring Christoph Waltz’s Nazi. It is wrong for a filmmaker to invite audiences to relish the torture of human beings (even odious Nazis), especially when the United States has a huge problem with torture in the war on terror.

The discussion of torture in IB is so much more complicated and unsettling than in just about any genre film. Usually action films just accept torture as automatically cool and fun; it’s not even questioned.

In IB, that first torture scene with the officer; he’s presented as brave and noble. He’s still a Nazi, you kind of want him to die—but the Americans come across as bullies and sadists, and he’s the one defying them out of love of country.

Landa is definitely horrible, and you want him to suffer. But he’s also really appealing as a character in a lot of ways, and he does end the war. And think about who you see in the film laughing at violence, and cheering on bloodshed. It’s Hitler—while watching a film.

I think IB is pretty honest about the appeal of torture and violence. But it also works insistently, over and over, throughout the film, to point out that to cheer on torture and violence is to make yourself like the Nazis. How is Aldo better than Landa? Landa kills innocents without remorse…and Aldo shoots those people in the basement without a second thought. What’s the difference?

@ Josh K

Anecdote: There’s a scene early in Saving Private Ryan wherein some German soldiers try to surrender, and the American soldiers say “What’s that? I can’t hear you,” and then proceed to kill them. The film does not want us to approve of this action. The one time I’ve ever seen the film in public – the first time, in history class – the aforementioned action was naturally greeted with enthusiastic cheers from the audience.

The point being, you don’t have to “invite” the audience to cheer inhumane behavior. If you depict it, they’ll do it. We can argue about whether it’s right or wrong to depict inhumane behavior at all – but if you’re willing to have it depicted, then you have to accept that the sadists in the audience are going to get what they want, no matter how you frame it.

I think you can depict torture (even torture of bad people) without making the torturer look cool. Torturers are petty and pathetic. But that doesn’t come through in Inglourious Basterds. They are theatrical (Eli Roth hitting a baseball bat in a tunnel), they have cool nicknames that make them sound potent (“Bear Jew”), they swing baseball bats gracefully and powerfully. And they go out in a blaze of glory. When they torture wimpy Nazis (like when Brad Pitt disfigures the German soldier who wants to hug his mother) the camera decides to cut away except for Eli Roth and Brad Pitt smirking at the aftermath.

I am arguing something similar to what Jonathan Rosenbaum argued about war films; despite the filmmakers’ intentions they usually end up glorifying war (http://www.chicagoreader.com/chicago/cutting-heroes-down-to-size/Content?oid=896882). Noah’s convinced me Tarantino’s intentions were not to pander to audience bloodlust, but he hasn’t convinced me Tarantino was successful.

‘Torturers are petty and pathetic.’

That’s just a comforting lie. Torturers can be anything.

‘I am arguing something similar to what Jonathan Rosenbaum argued about war films; despite the filmmakers’ intentions they usually end up glorifying war’

Like I said, if you depict it, people are going to enjoy it. Probably you are too.

(The story about Wes Craven walking out of Reservoir Dogs comes to mind. “[T]he film-maker was just getting off on the violence.” Oh, like you didn’t in your own movies, Wes? Or maybe he was just mad that Tarantino was being so blatant about it and giving away the secret.)

I think Jonathan Rosenbaum is kind of a dope, mostly.

Brad Pitt is a stooge in this film. He’s not a hero; he’s a sadistic dope. Eli Roth shouting in a Brooklyn accent about hitting one out of the park after killing someone who died for his country—is that really cool? It’s pretty uncomfortable, I think, and meant to be so.

You want Tarantino to pretend that the genre pleasures of torture and violence don’t exist. You want it to be an art film. He won’t do that, in part I think because he believes (correctly) that it’s dishonest. There *is* an appeal to revenge; there *is* something really satisfying in seeing Jews, who are usually portrayed as victims, get to be the heroes, and avengers, of their own stories. I mean, I’m not especially persecuted as a Jew, nor especially connected with my Jewish heritage in any meaningful sense, but I am thoroughly, thoroughly sick of Jews being presented as the beneficiaries of white nobless oblige, and/or of Jews on screen being nebishy emasculates. I don’t think those feelings are some sort of false consciousness, nor that they’re necessarily in all ways evil.

Tarantino acknowledges the appeal of genre violence and revenge. But he really does not present them as unproblematically heroic in IB. I mean, do you ever watch any other genre work? Torture is everywhere; look at an average James Bond film, and actually think about what he does to the villains, or how little personality or moral weight there is when he hits someone for information, or shoots his way through twenty or thirty people.

That’s the default; that’s how violence and villains are usually handled. People wring their hands about violence in Tarantino because he makes you think about it. The people who die in IB almost all have moral weight. They’re Nazis, but they’re heroes, they’re fathers, they’re people. Killing them is fun (because revenge narratives really are fun) but it’s never just fun. And, like, Eli Roth speaking Italian like a doofus, or shooting down on panicked unarmed civilians, is not exactly unproblematically cool.

Inglorious Basterds actually demands that you think about how American propaganda against Nazis makes us like Nazis. I think that’s brilliant, and absolutely a moral project.

“I think you can depict torture (even torture of bad people) without making the torturer look cool.”

You *can* do this…but only by depicting the torturer as evil and other. If you depict bad guy sadists, you don’t end up despising torture. You end up wanting to shoot the sadist.

I think the problem of talking about torture and violence aesthetically (and other than aesthetically) is actually extremely difficult.

I had read that Rosenbaum review before I think, and quite like it…except for the praise of Schindler’s List.

Or, what I’m trying to say is…torture is either justified because the tortured is evil, or it’s unjustified and then the torturer is evil. We seem to find it narratively very difficult to move beyond those positions; it takes a lot of work.

I am not conveying my idea very well. I am not saying that the torturer needs to be depicted as evil and as the other. You or I might become torturers if we had the male camaraderie thing going on and we were fighting some awful enemy, like Nazis or ISIS or Al Qaeda or whatever. But if we did torture someone, if we bashed someone’s brains in while our buddies looked on and clapped and laughed and applauded, we would not be powerful, or potent. That’s the biggest lie movies tell about torturers. In reality, that act would make us small and weak.

I rewatched the killing of the noble & brave Nazi officer with Noah’s comments in mind, and maybe Tarantino is coming close to my ideal depiction of torture. We see a long shot of Eli Roth swinging his bat (he looks small), we see the Nazi officer writhing in pain. But still, the other shots emphasize Roth’s rippling muscles, his flair for the dramatic, and his potency (he dispatches the Nazi fairly quickly, in a couple of seconds, with a few swings he makes the Nazi’s head explode like a tomato). And Tarantino doesn’t bother to show us the disfigurement of the wimpy Nazi. If he did that the right way, showed Brad Pitt struggling to disfigure some crying captive Nazi, that would have really hit home your point about Brad Pitt’s character.

Tarantino often cuts away from violence. I think he’s probably right to do that. The idea that images of violence in themselves would put people off—I don’t think that’s necessarily the way it works.

“if we did torture someone, if we bashed someone’s brains in while our buddies looked on and clapped and laughed and applauded, we would not be powerful, or potent.”

Is that really true? I don’t know that that’s really true. Torture is wrong and evil, but I think it’s too convenient to say that it makes us weak. That’s conflating virtue and power (which we love to do.) You can be strong, or the strongest, and do the wrong thing; even torture. The death camps didn’t make Hitler weak, in any way that matters. Dropping the bomb on Japan didn’t make us weak. It made us evil. Those two things aren’t the same.

As I understand it, the going theory (per Hitchcock) is cutting away from violence makes it more horrifying (and draws us further into the film) because we tend to involuntarily imagine the violence we don’t actually see.

Eli Roth told a story about a lady being mad at him for showing somebody’s Achilles tendon cut into in ‘Hostel’. Despite his telling her it wasn’t actually shot or shown that way, she insisted it was, and remained quite angry at him.

I think Josh’s point remains valid: Basterds can be read as a pretty weird political comment, making American torturers look cool in 2009. Sure, the guys torturing the Nazis are portrayed as dislikeable meatheads, but they are the ones who get the job done (destroy the nazi regime). So in that way it could be interpreted as a pretty artful justification of ‘The War on Terror’ etc… I’m sure its not the only way to read that film, and I dont think Tarantino consciously intended to justify Guantanamo … but thats how modern propaganda works, right?

They don’t get the job done! They totally screw up; they’d probably have messed up Shosanna’s plan because they’re such meatheads. The guy who saves the day and ends the war is Landa—the guy they torture at the end!

I mean, art is polysemic, so I can’t rule out any interpretation. But, like, a big part of that film is a premier for a film celebrating this Nazi who kills 300 people in an all out action battle. And you see repeated images of Hitler—that’s Hitler!— laughing hysterically at really unfunny scenes of people getting shot in the head and dying.

He didn’t intend to justify Guantanamo. The film is about American torture! And not in a 24, we must do this, way. It’s about how Americans torture and kill brave, honorable people, and innocent people who leave their kids’ orphans. And what is this in the name of? Ending the war? No, of course not; the war didn’t end with blowing up a movie theater. So then, it’s in the name of war films, isn’t it?

You know what’s unthinking propaganda for war? superhero films, action films, spy films; almost everything at the cineplex. Tarantino actually makes you uncomfortable about torture, so then people turn around and say, “he’s immoral!” I find it a little frustrating.

Like, I don’t think it’s an accident that you had to egregiously misread the plot in order to get it to be an endorsement of torture. The film is pretty careful about *not* doing the thing virtually all action films do, which is create iconic heroes who are good because they are violent, and vice versa.

Note, for example, that Shosanna doesn’t get to see her revenge.

Django is less careful about this (to put it mildly). But, in its defense, we’re pretty unwilling as a culture to show celebratory images of black people murdering whites in great numbers. I don’t think black people torturing white slavers works to justify Guantanamo, because Guantanamo is predicated in part on the idea of American virtue, which Django is pretty solidly against.

Noah, you keep bringing up really bad films we all agree on being bad, just to make Tarantino look complex and sophisticated in comparison. All the points you just brought up, sure, Tarantino is clever and reflects his own medium etc. But that just makes Basterds the thinking man’s 24. I dont know, I could be wrong, I still appreciate Tarantino for his mastery.

I never bought that the violence (or I guess genre pleasure) isn’t supposed to be fun in IB. For me the ending was cathartic; the elites that made the success of the Nazi party possible get the horrible, climactic death that, in other films, is usually reserved for interchangeable soldiers.

Tarantino has made it clear in interviews and in his films that they aren’t real life and that their violence can be enjoyed because it’s not real violence. He’s talked about how unsatisfying the end of Roots was, where the good guy lets the bad guy go because ‘he doesn’t want to sink to your level’. So in Tarantino’s films, the good guys do sink to that level. In real life, Germany surrenders, West Germany becomes an ally and then unified Germany becomes the richest country in Europe. In IB, the German surrenders and is on his way to prosperity and comfort and even says as much, then Tarantino stops the film so Brad Pitt can carve a Swastika on his head. Which gave me what I wanted in a film advertised as bad people killing Nazis. Lots of people say we’re supposed to be horrified that that happened, or that the Bear Jew beats a defenseless soldier to death with a baseball bat, but I don’t see it. Reversing the usual WW2 movie trope, the noble-suffering Jew and the sadistic, cool Nazi is fun.

There’s autocritique in IB and Django – slave owners enjoy watching ‘mandingo’ fights, the Eli Roth directed movie within a movie, but I don’t buy that it’s a critique of all viewers enjoying violence. The Nazi crowds cheering the movie are gross because the fiction they enjoy reflects their ideals, the Django mandingo fight is unsettling for basically the same reason. Not that the film in a film doesn’t problematize IB at all, but IB isn’t like Miss Bala, where violence is never cool or justified and reflects a worldview genuinely repulsed by violence.

Lots of films, like Zero Dark 30, have scenes where sympathetic characters mourn how evil violence and torture are even as it’s necessary to the narrative. Having Tarantino do that meta-textually is pretty similar.

“Reversing the usual WW2 movie trope, the noble-suffering Jew and the sadistic, cool Nazi is fun”

Thats the other side of the story, and I agree.

I’m not bringing them up because they’re bad. I’m bringing them up because no one says they walked out of them in horror, or that they really find them viscerally morally repulsive.

I’ve talked about Verhoeven too. I don’t know. What film do you want to bring up to have me explain why Inglorious Basterds is better? It’s better than just about everything. Like, do you want me to explain why Pulp Fiction is infinitely smarter about violence than crap like the Godfather or Goodfellas?

Tarantino isn’t mourning the violence though. He’s questioning it..and also enjoying it.

haha, no I dont think getting into ‘my favourite director is better than your favourite director’ will get us anywhere. Guess Im pretty much with you regarding the Godfather and Goodfellas, too. On the other hand, i would say The Sopranos to me are much more up to date in how violence and genre are used, compared to Tarantino. I always felt this is the show capturing the state of things post 9/11 most accurately.

I still haven’t seen the Sopranos…though everything I’ve heard about it sounds awful. The creator sounds like an incredibly self-impressed boob.

I was just asking about other directors because I’m honestly somewhat unsure where you’re coming from. If you don’t like violence in your films at all, I guess I can understand that; it’s just hard for me to see who out there who deals in action/adventure genre broadly handles violence more thoughtfully than Tarantino does (at his best, anyway.)

“I was just asking about other directors because I’m honestly somewhat unsure where you’re coming from”

yeah well we already talked about Verhoeven. I dont know why youd say i dont like violence in films at all, you also already know i enjoyed going through Haneke’s complete works. The Sopranos got so violent and depressing i had to take a break from it as well, but in the end i think that show had to say something (like Verhoeven and Haneke), but with Tarantino it always comes down to this nihilism. Maybe its I feel Chase, Verhoeven and Haneke are at least critical of the status quo one way or the other, while Tarantino is mostly just celebrating himself.

“The creator sounds like an incredibly self-impressed boob”

read any Tarantino interviews lately?

Nah, Tarantino in interviews comes off as a fan. You don’t hear Tarantino babbling about how he hates film the way the Sopranos guy goes on and on about how he’s better than everything on television.

Tarantino just is not in any way a nihilist. He’s obsessed with revenge films; you can love revenge films or hate them, but they’re about justice.

Funny Games is nihilistic precisely because it rejects revenge, and really sneers at the very idea of justice. Tarantino never does that.

He also creates real characters, who he loves. I don’t know how you can watch Death Proof and come away thinking he doesn’t care about the characters and what happens to them. The nihilist charge just baffles me. I don’t even know where that comes from. His films are just so filled with love—for film, for genre, for his characters, for his actors (Pam Grier, Samuel Jackson, Uma Thurman). He’s a director of plenitude and excess, not nihilism.

I’d honestly like to hear someone explain to me how Tarantino is nihilistic. It comes up over and over, and it’s the criticism of him I understand least. It makes no sense to me.

But! Though I would like to hear that explanation, I’m going offline for a while, and things are heated enough here that I think I’d better close it for the moment. We’ll open up later. Thanks all.

i’m just as baffled by your interpretation of Haneke. The idea that revenge equals justice (and the rejection of revenge equals nihilism) is really really strange to me. It just seems to come straight out of the kind of bad action films you mentioned before.

think I already did my best to explain why Tarantino often feels nihilist … dont think I can say it any better unfortunately.

Haeneke *isn’t* nihilist now? Seriously? Funny Games wants the bourgeoisie to eat itself and leave behind death and a tv monitor displaying snow. I’d sort of be shocked if he didn’t actually consider himself a nihilist.

I don’t see any explanation of why Tarantino’s a nihilist…but I guess that’s the way it goes.

Magnificent.

Though I don’t think Haneke does consider himself a nihilist, or is one. He’s as moralistic as Tarantino – it’s just that his morality totally sucks.

Huh. Is he just a Euro-lefty sort, then? I guess I can see that…

I really like the television scene in Funny Games. That’s the best part of that film.

For all I know, maybe he votes liberal (that is, libertarian), but certainly I think anti-capitalist and anti-conservative.

Tim may already have mentioned Haneke’s famous remark, that he would congratulate any one who walked out of Funny Games, because they proved they didn’t need to receive the film’s message.

Here’s part of an appreciation with a couple of (it seems to me) indicative quotes from him: https://books.google.com/books?id=ofmkjZbqPpwC&pg=PA154

“Euro-lefty”

yeah sorry to interrupt your discourse with all these un-american ideas haha.

So maybe Im just not american enough to identify 100% with Tarantino, just like you seem to misunderstand Haneke’s european perspective.

I kind of doubt that’s the issue. I’m not against european lefties; I’m a socialist and all.

@ Tim

It’s one thing to say that a film has to be understood in the context of the country it comes from; it’s another to imply that foreigners are incapable of understanding it.

In any case, I’m half Austrian and my first language was German. If anything, I think I’d hate Haneke less if I didn’t feel disgraced by association.

I don’t think I implied anyone born outside of Europe can’t understand Haneke. All i said was different cultural backgrounds seem to inform contradicting perspectives and interpretations. Maybe its not the case here, dont know if we’ll ever get to the bottom of this though.

I can’t see Haneke as literally nihilist either, but perhaps you don’t mean it literally. On the contrary, I would call him a moralist through and through. Funny Games is a moral polemic which criticises the viewer for enjoying the vicarious spectacle of violence — a moral polemic is ipso facto not an expression of nihilism.

(I hate the movie, incidentally. I’m not saying he’s my favourite film-maker, just that he’s not a nihilist. I feel the reverse of your position, Noah — I’d be shocked if Haneke did consider himself a nihilist)

Likewise Hour of the Wolf and Cache both express a distate for the hypocrisy and coddled entitlement of the bourgeoisie. Again, not a nihilist position.

…I suppose you could see all these films not as genuine expressions of moral disapprobation, but a sort of reductio of bourgeois moral principles that Haneke does not, as such, buy into. i.e. Haneke isn’t going “How dare you, you bourgeois, enjoy violence! You are terrible people!” but rather “Ha ha, you bourgeois, you enjoy violence. Well, how do you feel if I show you your hypocrisy? (which, as far as I, Haneke am concerned, is neither here nor there, but at least you’ll be upset about it — ha ha)”. But this doesn’t seem to me a plausible interpretation.

Graham, I apologise for calling you a jackass in that other thread. That wasn’t a helpful way for me to express my complaints about your commenting style and tone.

Okay, you’ve all convinced me that Haneke isn’t a nihilist.

Clarification: This alone, of course, doesn’t disqualify Haneke from nihilism. But I do think his work carries an implication that he believes in the possibility of building a non-capitalist, non-conservative better alternative to society as he sees it today – even if he doesn’t have a very clear idea of what that society might be.

Further clarification: My saying that Haneke is not a nihilist is not intended as a defense of that filmmaker. I mentioned Michel Houellebecq yesterday as an example of a truly subversive artist, as opposed to Haneke’s phony subversiveness (also a truly empathetic artist, as opposed to Haneke’s loveless alleged humanism) – and Houellebecq really is a nihilist.

“a distaste […] Again, not a nihilist position”

I spoke loosely here — I meant disapproval, not distaste, which would be compatible with nihilism. (Nihilists can still like and dislike things)

@ Jones

Thank you, and if you’re worried about it, don’t be; I don’t remember it and I’m sure I deserved it. On which note, I’m sorry for all the things in that thread that I should be sorry for.

The impression I’ve gotten from talking with some people who think Tarantino is a nihilist (or that his films, at least, are nihilistic) is they believe a lot of his violence is presented as amoral. Most action movies work with violence as evil, good, or necessary (and thus either good or excusable), but Tarantino allows for ambiguity, complications, and (sometimes) a sense that moral judgment may not matter or apply.

For example, Butch kills a more or less innocent guy off screen in Pulp Fiction, and no one really cares. Beating someone to death is probably wrong, even in the midst of a boxing match, but the film doesn’t explicitly judge that act. If the movie makes it clear that, overall, violence is dangerous and not particularly rewarding (even in the scene discussing the killing), this message may not reach people who’ve already judged the morality of the movie based on some of its parts or (just as importantly) on tone.

I think Taratino’s mix of ironic distance and matter-of-fact-ness alienates a lot of folks.

Huh; that’s interesting. Butch’s killing that guy seems like one of the most conventional moves in that film; the hero kills people, and it doesn’t matter, because he’s the hero.

I guess what you say makes sense. It’s the fact that there is actually a questioning of the typical morality of genre that leads people to see it as nihilistic, just as the questioning of violence leads people to see it as particularly violent.

I dont think Butch is the manifestation of Tarantinos nihilism. First thing i’d think of is Vince shooting the kid in the car by accident, and how this meaningless death just is there to create hilarious situations. I dont really get the feeling Tarantino is criticising genre here or anything, he just needs violence to create a sensation. But its about nothing.

“Haneke’s loveless alleged humanism”

I agree thats the problem with him, Haneke definetely has been gazing into the abyss for too long … maybe that’s what he has in common with Tarantino (and the rest of us).

Tim, both bits of violence feature what is essentially murder, and neither elicits compassion from the characters (nor is it sought from the audience), and their respective actions exist mainly to set up what ensues.

But, they also tell us a good deal about the people we are watching (and the world they live in), while reinforcing the general message. Whatever appeal it may have to the characters or audience, the criminal underworld is ridiculously dangerous and unlikely to be rewarding for anyone involved. Characters die or are hurt by chance, and while they also survive or escape unscathed by happenstance, the former is (over even a short period of time) far more likely–all of which is in line with a standard, pulpish tale of morality: don’t do crime or drugs, or you will probably die an early, absurd, and disquieting death without anyone shedding a tear.

But I understand not everyone is going to get that from the movie. The message some will take away is, ‘film violence is cool’. To be fair, that’s at least part of what Tarantino seems to me to be saying.

But, I should say, you did a better job of explaining the ‘Tarantino is a nihilist’ argument than I did. It seems to me believing the violence on screen serves no purpose (or none beyond titillation or sensationalism) is a key element.

Sometimes, in the less tightly scripted moments (e.g. the Bride’s slaughter of the 88 Keys in ‘Kill Bill vol. 1’ or the not-in-the-published-screenplay violence of ‘Django’), the violence probably is just sensational, but not in a way that is obviously worse or more smarmy than gratuitous killing in any other popular action or horror flick.

Tavis – the reason why i thought Butch wasnt a good example is that this scene is there to prepare us for the transformation this character will be going through. He is a traditional hero in the sense that he illustrates a lesson, he has become a better person by the end. So i don’t think that “it doesn’t matter, because he’s the hero” (Noah).

“The message some will take away is, ‘film violence is cool’.”

I think this would be a common critique of Tarantino, and i guess it’s worth considering. Kind of the same dilemma with Oliver Stone’s Wall Street (or most gangster and war films for instance): No matter how subtle, critical, ironic or complex the director wants to be, if you focus on the bad guys it ends up being misunderstood as advertising or getting reappropiated as the glorification of some evil shit.

Butch isn’t a better person in any particular way that I can see. He’s the hero; he kills people. That’s true of the boxer; it’s true of the people assaulting Marsellus. You don’t find it nihilistic because it conforms to genre conventions.

The bit where he kills the guy in the car by accident…that’s an instance where violence *is not* cool. Imagine if this were goodfellas. It would be about how vicious and mean these guys are, and how tough. Instead, it degerenates into sit com, where the brutal killers are seen as incompetent stooges and fuck ups, roundly mocked by everyone. Violence diminishes them. And not that long thereafter, Jules forswears violence, and walks out of the film, while Victor keeps on his path, and is humiliatingly murdered coming out of the toilet.

That’s no nihilism. That’s about karma and the stupidity of gangster tropes. It’s a moral statement.

Tarantino cutting away from violence might be as much to appease the MPAA ratings board as for dramatic purposes. I believe I recall him speaking publicly about his troubles with the MPAA. International cuts of his movies–or at least Kill Bill–have more violence left in.

I think it’s fascinating that Tim thinks Butch becomes a better person by the end. Why is he a better person? He’s okay with killing at the beginning; he’s okay with killing at the end. The differnce is that the people he kills at the end are presented as debased and evil (in part through the use of stigma against poor rural whites), and he’s seen as protecting the innocent. He becomes a superhero, so he’s moral—except that superhero morality is really poisonous, and is just based on giving the hero a supposed excuse for extreme violence.

The Butch section is the most conventional, and therefore the least moral part of the film. But it fits with film conventions that mean “morality” to viewers, so somehow it’s not nihilistic, while the parts of the film that actually try to question how film morality work are promoting violence.

Noah – my point was, Butch is not the best example of what i consider Tarantinos special brand of nihilism. But again you keep attacking the same straw man, as if anyone was here to defend Goodfellas or superheroes or whatever. Sure, I should have put quotation marks around “better person” to avoid misunderstandings.

“The bit where he kills the guy in the car by accident…that’s an instance where violence *is not* cool.”

Its true that Vince doesnt look that cool here. It’s Tarantino who is cool, and that’s what Pulp Fiction is mostly about i think. Again, that’s the nihilism i mean.

Also, you can now quote me “Tim thinks Tarantino is cool”.

But yeah, theres also something to your interpretation of the Jules and Vince part. Maybe people are less likely to idolise them than the gangsters usually portrayed by Al Pacino, DeNiro or Joe Pesci. On the other hand, these two characters were so influental, they have become icons just like Scarface or whatever, so its kind of the same issue as with IB: torturing soldiers or mobsters can say, ok i know im not the brightest guy, but im cool and could kick your ass anytime. I think the only way to really avoid identification with the perpetrators of violence might be to not make them the stars of the film and instead take the victims perspective.

Tim, you’re the one who said Butch learned something; you’re the one who’s saying that section is less nihilistic than the others. You’re saying you find moral lessons in conventional superhero narratives, but that bits that question that are nihilistic. If you don’t like where that line of thinking takes you, you can’t blame me.

Victor doesn’t kick anyone’s ass! He gets shot coming out of the toilet! Every time anything important happens, he’s sitting on the john! How is that cool or impressive? He’s a complete fuck-up. He’s charming and charismatic, but he’s not “cool”. The only people he effectively kills are unarmed college kids.

Same with IB. They’re not made cool by their violence, for the most part. There’s some heroism in killing Nazis, which it seems hard to argue with, but the guy who ends the war is Landa, who is pretty clearly despicable. Aldo’s just mean, and kind of laughable.

You know who is made cool by violence? Butch; the guy you say *doesn’t* demonstrate nihilism, the part that you see as teaching some sort of moral lesson.

Tarantino frequently takes the victims perspective! The whole first section of Inglorious Basterds you’re identifying with Shosanna and her family. The scene where Marvin gets shot is filmed from his perspective. Tarantion constantly puts you in this masochistic position anticipating violence and fearing for victims. It’s one of his most characteristic moves. Like, the entire first half of Death Proof? You don’t think you’re supposed to sympathize with Victor when he gets shot? We’ve already spent a lot of time with him; he’s a sympathetic character.

Tarantino is somewhat ambivalent, it’s true. But I just don’t see how you can be even minimally attentive to his films and come away with the idea that (a) perpetrators of violence are always cool, or (b) you never identify with the victims.

Ordell’s a good example. Ordell thinks he’s in a blaxploitation film; he thinks he’s cool an dangerous as he listens to Johnny Cash. But the only people he kills are his employees, mostly by just betraying them in completely despicable ways. Every time he tries to pull something on Jackie Brown, he ends up castrated or dead. He’s not cool; he’s a jerk who thinks he’s cool, and gets taken down for his trouble (and he’s not shot by Jackie Brown either; she sets him up, but it’s the idiot cops who kill him.)

I guess it’s possible someone could look at Ordell and say, wow that guys awesome and cool; great! But if you do that, it’s because you’re like Ordell; you’ve seen too many blaxploitation films (or the equivalent.) Tarantino’s just using a trope, and working against it; if people are so invested in the trope that they can’t see what he’s doing, it’s hard for me to see how Tarantino is somehow uniquely promoting violence or nihilism.

Tarantino even encourages you to mock Ordell explicitly. Melanie says he’s stupid and that he doesn’t know what he’s doing over and over. Louis points out that he’s handling his business badly. Simone runs away with his money and makes him look like a putz. It’s not subtle.

And again, I don’t see how you can say that Tarantino’s main goals isn’t to make film violence cool. That Lando ends the war is neither here nor there. Tarantino knows that we know how the war ends so knows that we don’t care if Germany’s eventual defeat is shown within the film, we care that the film villains get comeuppance.

Haneke’s goal is clearly to make us be viscerally repulsed by violence. Tarantino has us enjoy it. Marvin getting shot takes up about one minute of screen time after a long section of the viewer identifying with the thugs and their now iconic jokes. Shoshana hiding from the Nazis sets up us to root for some prisoner execution, as well as getting the viewer to get behind her goal of burning Nazi’s alive.

And I do think that his theme is that being a perpetrator of violence is cool. Landa is pretty cool when laughing about killing Jews and pulling out an even bigger pipe at the beginning of IB. Victor is cool, (death not withstanding, he gets far more humanized than his victims in the film) Butch is cool, Jules is cool. So is Aldo, a character with a similar biography as Tarantino who ends the film committing an act of torture on a very deserving character just when we think that Landa’s getting away with gleefully killing women and children. Aldo even says “I think this is my best work ever” or something after, at the end of the film. Tarantino’s work is way more about celebrating violence than a condemnation of it.

(I like IB, and I think one of the things to take away from it is that film violence is inherently cool, no matter who the aggressor, so if you show Nazis callously killing Jews you’re on some level going to be impressed, so here, enjoy some Jews callously killing Nazis.)

Yeah, Jules is super cool whining about how Jackie Brown is going to shoot his balls off. Victor is super cool wearing a ridiculous volleyball outfit or getting shot coming out of the toilet. Aldo is super cool speaking bad Italian with an appalachian accent. Louis is supercool losing his car n the parking lot and shooting Melanie out of irritation.

Seriously, do you even watch the films? Because it seems to me Tarantino is a lot less convinced of the coolness of violence than you are. The only way you can see all the violence in Tarantino as cool is if violence is cool *to you*. So cool that no matter what contrary evidence Tarantino presents, it’s still cool.

Violence in Tarantino is sometimes cool. But it’s also a lot of times not cool; it’s stupid, and ugly, It diminishes people. Tarantino certainly acknowledges the attraction of violence, and he fulfills genre expectations sometimes (with Butch, with the Bride often, with Django in some ways.) But he also consistently presents people who use violence not just as bad (which is cool) but as stupid, as fuck ups, as bumblers and thuggish twits.

As for Victor; Victor is sympathetic—but sympathetic isn’t the same as cool. Victor is the first; he’s not the second (except perhaps when he’s dancing.) Victor is defined by the fact that he’s *always on the toilet*. In what universe is this cool? How is the fact that he is always on the can supposed to make him a super cool gangster you want to emulate? The argument seems preposterous on its face.

Also, the point of IB is not that we know how the war ended, so who cares if you show Hitler dead. The point is that the film is obsessed with filmic representations, and the distance between film and reality. Killing Hitler is a film fantasy; it’s a wish, which is fulfilled, but recognized as impossible *which is different from all those other war movies where individuals make a substantial difference in the war.* More, the wish for individual violence, and for Hitler’s death, is linked to Hitler’s own delight at the film in which a German Nazi superhero mows down Allied forces.

I think the main confusion may be the claim that Tarantino’s goal is to make violence cool. Tarantino doesn’t need to make violence cool. No one needs to make violence cool. Violence is default cool. People think violence is cool even when it’s committed by characters who are shown to be clowns and dopes and fuck-ups. Tarantion thinks about the attraction of violence; he uses the attraction of violence. But our entire culture is committed to making violence cool. Tarantino doesn’t need to do any work to make it so.

@ Noah

Excellent. (I’d add only that everybody else’s culture is likewise committed, forever.)

So that’s what the Quakers have been doing all this time.

Well, some of them were too busy buying and selling slaves to spend much time reading fiction, violent or otherwise.

Seriously, the Quakers are part of our culture – English, then American – and of course always a much smaller part than the portion who enjoyed violence, even if we assume that portion didn’t include Quakers, which of course it did.

“The only way you can see all the violence in Tarantino as cool is if violence is cool *to you*”

Right. Also, we all know the people who see racism everywhere are the real racists.

Well I’ve said all I had to say before and we just seem to be going around in circles anyway …

Racism is everywhere. The notion that violence is cool is also everywhere.

Pointing to someone who says “racism is everyhwere” and saying, “this person is racist” is a thing that happens. You can follow through on the analogy, I think.

Tim, some people misunderstand (or don’t even try to think through) Tarantino’s movies, and just receive them as trash entertainment where empty,fake violence is its own reward. But that’s thematically inconsistent with a lot of his work. If it isn’t his intent, and requires a willfull misunderstanding or ignorance on the part of the viewer to come to that conclusion, it seems odd to call Tarantino a nihilist.

Some of his fans are, perhaps (though more likely they don’t have time for thought out ideology), but that isn’t his fault. He has no responsibility to stop making movies the way he wants to just because somebody might think some of the more messed up violence is simply cool and nothing else. It seems to me you’re misplacing blame here.

From what you’ve written, I assume you think Tarantino could do more, be more heavy-handed, and less like himself in order to convince these people they are missing some important points in his movies. But there is little reason for him to abandon his own desires, creative impulses, and success just to fail to convince some people who probably wouldn’t care anyway and wouldn’t watch if that’s what he did. But if he doesn’t do that, he’s a nihilist? I wouldn’t be surprised if he put in stuff like the 88 Keys sequence in KB1 just to turn people who think like you so far off, you’d stop talking to him. There’s no way he can meet your expactations, and no reason he should.

To put it another way:

If Noah can decide you must think depictions of violence are, in themselves, cool, despite your complaints running contrary to that notion, is that proof of nihilism or some moral failing on your part?

hm ok I think we’re stuck here with rhetoric tricks. It was an interesting discussion anyway, thanks and no hard feelings!

Tavis, didnt see your comment when I replied to Noah. I will try to reply soon.

I don’t think that’s the wall we hit, but fair enough. I enjoyed the discussion.

Same here.

Thats the question, is it a misunderstanding to think Tarantino (= his films) in the end glorifies violence? I dont know if Tarantino (= the person) ever claimed to criticise the representation of violence with his work. From what I remember his angle in interviews was usually like “chill, none of this is real, its just a style”. That doesnt mean his films cant have a different message though. Just to me it seems if his goal was to question violence, I dont think hes very good at it.

“you must think depictions of violence are, in themselves, cool”

now i really dont know how anyone was seriously getting that from me. What i was saying is, showing acts of violence from the perpetrators point of view (i.e. we follow their story, not the victims) is problematic because it usually creates an identification that is more powerful than any critical intent the author may or may not have. I mentioned earlier i have a hard time identifying with anyone in Tarantinos films, Pulp Fiction is just full of idiots and assholes. Which brings us back to this nihilism thing.

I don’t know, seems im still just kind of repeating myself. I think there are contradictions and misunderstandings on both sides of this argument, but i really can’t figure it all out now. It certainly would be easier to discuss if i didnt have to get through 50 paragraphs to reply.

Tim, you say you don’t identify with any of the characters in Tarantino, adn think they’re assholes and jerks. At the same time, you say they’re cool because of violence. ???? It seems like those two things don’t make sense together. Or, to put it another way, you need to engage in some very ungenerous interpretations of Tarantino’s intent in order to position yourself as smarter than the material.

It has been a fun discussion! No accusations of moral failing on my part; I think everyone kind of thinks violence is cool (not excluding myself.)

One thing that commenters and Noah touch upon but haven’t dug into here is that Tarantino’s movies aren’t about real-life cultural issues or historical events so much as they’re about film culture and film history. As such, any insight he has into race, violence, etc., is going to be refracted through film. This is a potentially useful thing, since it’s often useful to tease out what is taken for granted (aka ideology) of a given culture through its representations. Moreover, you draw a bigger audience than you would in a cultural studies journal. As J. Lamb and others point out, it can be problematic, too. After all, to mediate or critique a representation through representation is to re-represent it, and in so doing to risk perpetuating the object of critique. I guess the question is whether Tarantino is critical enough in his thinking and careful enough in his filmmaking to avoid the pitfalls of perpetuation. This is where aesthetics and politics meet, and maybe this is center around which our argument has been circling all along? To borrow a phrase, we’re asking if Noah is being dialectical enough.

As opposed to the other way of critiquing a representation in film (or any other visual art), which is… what, exactly?

While we’re at it, maybe we should ask whether he’s being orthodox enough, in the religious sense.

I would say Noah is here being more subtle than his critics, for the same reason that Tarantino is more subtle in his treatment of violence than, say, Kubrick in the ostensibly anti-war Full Metal Jacket (which doesn’t negate the fact that Kubrick is a greater filmmaker than Tarantino), and for the same reason – they’re not stuck on trying to square the circle of showing violence without it giving the audience pleasure.

Kubrick, bleah. I like Tarantino a lot better…

Part of me suspects that artistic greatness matters only in the sense of military greatness – that is, yes, Stonewall Jackson is probably the best general in the war, but he’s on the wrong side. (And of course, conversely, Ambrose Burnside is on the right side, but he still sucks. So you go with the best general available on the right side – hello, Ulysses.)

I was joking about the dialectical thing… Sorry. I think the better question is whether Tarantino is dialectical enough, meaning that what’s at stake is whether he’s working hard enough to unpack the power relations expressed in the films and genres he loves.

As to the question about re-representation, you’re totally correct. Any critique entails the reproduction of its object. This isn’t a bad thing, it just means that as critics we have to be careful about how we proceed. So maybe the real question is whether Tarantino is careful enough when he repurposes prior representations in an effort to create a new perspective on them and their subject matter?

I should add that I’m not a huge fan of Tarantino, but I do think his films raise interesting questions about filmic representations of violence and its consequences (ditto race, less so class). The challenge is that he’s raising these questions about film through film, so it’s sometimes hard to distinguish when he’s probing a given mode or tradition of representation and when he’s embracing it. As a result, it’s hard to make a bulletproof claim about the degree to which his films invite us to question those modes and traditions and when they don’t. And as others have said before, that’s a good sign that what he’s doing is art.

I agree with all that – except I’d say it’s not a question of whether Tarantino’s use of genre devices creates a new perspective or not. Sometimes he does, sometimes he doesn’t, but both can be valid – unless you think all genre is morally deplorable, which Tarantino obviously doesn’t.

I would say Tarantino gets in trouble when some of his own uglier obsessions take over – e.g. castrating the gay rapist southern white trash, in Pulp Fiction AND Django Unchained (so he’s more or less bracketed his career so far with that).

That all makes sense, Nate. I think Tarantino’s success varies pretty widely from film to film in terms of questioning tropes and filmic representations. Inglorious Basterds seems brilliant to me in its use of World War II film to talk about our ideas of World War II. Django is much more uneven, in part I think because Tarantino doesn’t actually engage much with slavery films. And he doesn’t engage with slavery films because (a) there have been way fewer representations of slavery on film, and (b) because the representations there have been tend to lean towards art films or message films, and Tarantino doesn’t care about those. It’s telling that he picks up Mandingo fighting from 70s exploitation, but that there really is very little reference to Birth of a Nation or Gone With the Wind (the southern belle seems more like a general received trope in Django, rather than a specific reference to the film.)

Instead, he uses Westerns…and he does some interesting things with that, but it ends up being about questioning westerns via slavery, rather than questioning slavery via westerns, which is okay, but leaves the representation of slavery largely unquestioned (which is a disaster when it comes to Steven especially, I think.)

Graham, the differences/parallels between the Deliverance lift and Django are pretty interesting too, I think. Tarantino obviously isn’t troubled at all by vicious hillbilly steroetypes—I don’t think it occurs to him that there might be a problem there. On the other hand, he certainly is aware of racism and stereotypes in Django; that’s what the film is about. He’s just not able to deal with them in a thoughtful way.

That is, it’s not that Tarantino thinks he’s wrong, or we’re wrong, to see Jules as cool in the first part of Pulp Fiction and enjoy him for that. But he does think that maybe there’s something more important than that.

@ Noah

I think Tarantino has a much deeper issue with gay men (or male gayness) than with hillbillies – though maybe such hillbilly issues as he does have come from reading southern mannerisms (or the stereotype of southern mannerisms) as effeminate.

(cf. Brian Schwietzer on Eric Cantor a few years ago: “Don’t hold this against me, but I’m going to blurt it out. How do I say this … men in the South, they are a little effeminate… They just have effeminate mannerisms. If you were just a regular person, you turned on the TV, and you saw Eric Cantor talking, I would say—and I’m fine with gay people, that’s all right—but my gaydar is 60-70 percent. But he’s not, I think, so I don’t know. Again, I couldn’t care less. I’m accepting.”)

The though occurs: Maybe Tarantino noticed in retrospect that Harvey Keitel and Tim Roth hugging it out at the end of Reservoir Dogs was a bit more personal than he’d intended.

Nate:

“So maybe the real question is whether Tarantino is careful enough when he repurposes prior representations in an effort to create a new perspective on them and their subject matter”

Thanks for setting things straight here. Also yes to everything else you wrote. Can’t believe we’re all agreeing here after all.

Noah:

“you say you don’t identify with any of the characters in Tarantino, adn think they’re assholes and jerks. At the same time, you say they’re cool because of violence. ????”

No, what I’m trying to say is I think Tarantino is saying that they’re cool (intentional or not).

Graham:

“Kubrick in the ostensibly anti-war Full Metal Jacket”

Now, I think Full Metal Jacket has the same problem as Tarantino in regards to identification. The movie takes the perspective of the US military, and no matter how fucked up this institution is portrayed to be, the film makes us look at it from the inside. So even if Kubrick has nothing but the purest intentions (criticise the Vietnam war and the US military), on a subconscious level he invites us to identify with the evil he wants to criticise. Again, the difference i would see compared to Tarantino: Kubrick has an urgent message, and most of the audience will get it.

If you want an example of *real* anti-war propaganda – and I know youre gonna hate this – is Nakazawas Barefoot Gen. This comic book is strictly taking the victims perspective (the average population, including soldiers), and you actually get an idea of the horrors of war and destruction. And that perspective allows you to really question things like the very existence of the ‘military-industrial complex’ etc. Of course, this is not as much fun as Tarantino, Verhoeven or Kubrick, its just depressing as fuck. So I’m not saying every movie should be like that either, ok?

best, Euro-Lefty

I would say the difference is that Tarantino admits he enjoys the violence he depicts, while Kubrick pretends he doesn’t.

Something like Barefoot Gen is in even deeper denial than Kubrick. It doesn’t make you question the military industrial complex, because it doesn’t even try to seriously address the question of why anybody fights wars in the first place. (Neither does Tarantino, but he at least acknowledges the fact that violence is fun.) What it does is invite you to feel good about yourself for deploring the military industrial complex.

Love,

American-Austrian lefty (in that order of nationality, but I couldn’t help being both to some extent even if I wanted to)

haha ok lets not get started on politics

cheers

self-satisfied tree hugger

Barefoot Gen is a giant steaming pile of crap.

“A story of world-historical import and great human tragedy is always improved by warmed-over melodrama, poignant irony, and random fisticuffs. Stirring speeches about the horrors of war are feelingly juxtaposed with scenes of anti-militarist dad beating the tar out of his air-force-volunteer son. On the plus side, though, drill-sergeant brutality set pieces are apparently the same the world over. Also, to give him his due, Keiji Nakazawa stops having his characters beat each other up for no reason every third panel once the bomb drops. Tens of thousands of civilians running about shrieking as their flesh melts is enough violence for even the most impassioned pacifist adventure-serialist. It’s okay to have Gen rescue the evil pro-war neighbors from their collapsed house and to have the evil pro-war neighbors refuse to help dig out Gen’s family and to have the sainted Korean neighbor help carry Gen’s mom to safety as long as you don’t have Gen and the Korean pummel the evil pro-war neighbors with a series of flying kicks as the city burns. It’s all about restraint. – See more at: https://www.hoodedutilitarian.com/2011/08/hiroshima-tit-nepotism-summer-reading/#sthash.hbCcgys8.dpuf”

That is one horrible comic exploiting massive tragedy to pretend to profundity.

Also, presenting victims as nothing more than victims isn’t actually a way to treat them with dignity, nor necessarily to create compassion.

fwiw, it’s my understanding that Kubrick didn’t intend full metal jacket to be an anti-war film, really. It’s a coming of age narrative in which violence makes you knowledgeable/cool/adult, and I think that was more or less his intention.

Haven’t seen Jackie Brown.

And film violence is not inherently cool, or fun. Most action movies are just tiring and un-involving. Tarantino sets it up so seeing POWs getting executed is a release. He knows what he’s doing, he doesn’t just happen to have violence that just happens to be fun to watch.

And I’m not really projecting my own feelings onto an audience that doesn’t exist. From the New Yorker review of IB: ‘Moral callousness has been part of Tarantino’s style in the past. In “Pulp Fiction,” his merry roundelay set among Los Angeles lowlifes, the aggressive acts that the characters commit against one another are so abrupt and extreme that they become funny. The movie’s outrageous panache gave the audience license to enjoy the violence as lawless entertainment.’

And Tarantino on violence: ‘To say that I get a big kick out of violence in movies and can enjoy violence in movies but find it totally abhorrent in real life – I can feel totally justified and totally comfortable with that statement. I do not think that one is a contradiction of the other. Real life violence is real life violence. Movies are movies.’

So it’s not an accident that Jules and Vince get put on t-shirts and a bunch of imitators follow Pulp Fiction featuring funny-cool killers. And yeah, Vince and Jules are humanized and have flaws, but what defines them more is the dance, the foot-rub chat, the hamburger bit.

I agree that IB is about the power of film violence, but I don’t think Nation’s Pride equates viewers who enjoy IB with real-life movie violence loving Hitler. It’s about the power of good films to fight evil. The Nazi audience laughs at the film of people dying, then the film laughs at them as they die.

How is it about the power of film to fight evil when everyone who watches the film knows that (a) the Nazis were not defeated in this way, and (b) the person who fights evil most effectively is Landa?

Other people saying that some other people over there enjoy the film in the wrong way…I don’t know. I’m not impressed. And…Tarantino expressing serious reservations about real life violence doesn’t necessarily suggest that he’s not approaching violence seriously, does it?

Action movie characters are supposed to be action movie characters. If you’re not moved by action films at all, more power to you, but you’re meant to identify with Tom Cruise in the Mission Impossible films pretty obviously. They’re not that complicated. So, somehow, the fact that Tarantino is more complicated makes him more culpable? How does that work exactly?

The dance, the foot-rub, and the hamburger chat are all doofy/nerdy bits that have little to do with violence. They’re presented as doofy guys who are appealing. As opposed to Bruce Willis in die hard, who is presented as awesome because he kills people. Travolta is not presented as awesome for killing people. He’s presented as a fuck-up for killing people and as cute when he dances. Ergo, the film promotes violence? I don’t get the logic there.

Kill Bill functions a lot more like a standard action film; the Bride is cool because she’s super violent, like Clint Eastwood.

@ Noah

I think we’re supposed to disapprove of the war machine as represented by the drill sergeant, the “Get some!” guy, the officer who’s waiting for the “peace craze” to blow over, and so on – and to some extent it works: I doubt W. Bush would feel flattered by the film.

But we do end up feeling impressed by them, because they have gusto, and totally unimpressed by frat boy protagonist, who has neither that nor enough conscience to make a difference nor anything else – so in effect the whole thing does become a kind of accidental fascist coming of age story, where the only time he’s compelling is when he’s become part of the machine at the very end, walking through the jungle and singing the Mickey Mouse song with all the other lost children of the ’50s.

@ Isaac M.

Yeah, because they’re badly executed. That’s not critiquing violence, that’s just trying to make violence fun and failing.

Tim, although almost everyone in PF victimizes someone else, most of them are also victims, and all of them are potential victims. It is very much a ‘live by the sword, die by the sword,’ sort of film with a lot of role reversals. At least, that’s how I see it, but I understand if you don’t. Thanks for the discussion.

A critique of war films that I think works pretty well: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V81uW2c6fi0&t=25s

A few points on FMJ (forgive the digression)–I served in the Marines and to some degree the film contrasts the idealism of boot camp with the realities of Vietnam. Boot camp gives the “ministers of death” brainwashing and marines in the field are counting the time until they leave.

The novel the movie is based on, The Short-Timers, is much more anti-war (or at least anti-Vietnam) than the movie. Joker ends up going native with the VC in the novel. I think Kubrick forced the “happy ending” in the film because he was worried about how the book’s tone would affect the audience. I can’t remember if I read that this was his decision or the studio’s, but I know the author wasn’t happy about it.

Interesting.

Tavis – cool, thank you too!

Noah: “presenting victims as nothing more than victims isn’t actually a way to treat them with dignity”

Dont know why you’d say Nakazawa doesnt present the victims (including himself) with dignity? did you read the complete story? I thought he gave a rather complex picture of both the population of Hiroshima and Japanese society … I could already guess you wouldnt agree, but i really dont know where the hyperbole comes from. But maybe Barefoot Gen is a debate for another day – I just wanted to add that i still think Tarantinos idea to rewrite history and reverse cliches to some degree with IB is great (even though it has its problematic aspects too, as we discussed). But i dont think revenge is the only way for a movie to show victims have dignity, or to serve justice. You suggested that revenge equals justice when we talked about Haneke before, and to me thats really the definition of a problematic Hollywood trope. Its also one of the ideas Tarantinos films reinforce I think.

I think revenge certainly *is not* the only path to justice! It’s a horrible way to think about justice…but it is thinking about justice. It’s not nihilism, was my only point.