I was recently re-reading Lillian S. Robinson’s Wonder Women: Feminisms and Superheroes (Routledge 2004) and came across a striking take on the She-Hulk, which I had forgotten about since my last reading of the book. Robinson begins her treatment of the She-Hulk by reminding the reader of Judith Butler’s account of gender as “… a corporeal style, an ‘act’ … which is both intentional and performative, where ‘performance‘ suggests a dramatic and contingent construction of meaning” (Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, Routledge 1990, p. 130) and as “a stylized repetition of acts” (ibid, p. 140). Reflecting on the She-Hulk’s overt sexuality and instantiation of feminine stereotypes (e.g. fashion, flirtation), Robinson asks if John Byrne’s take on the She-Hulk amounts to a “gender performance that is at the margins and is transgressive of societal rules” – that is, if there is any way to understand the She-Hulk as transgendered. Her answer is no less interesting for its being negative:

I was recently re-reading Lillian S. Robinson’s Wonder Women: Feminisms and Superheroes (Routledge 2004) and came across a striking take on the She-Hulk, which I had forgotten about since my last reading of the book. Robinson begins her treatment of the She-Hulk by reminding the reader of Judith Butler’s account of gender as “… a corporeal style, an ‘act’ … which is both intentional and performative, where ‘performance‘ suggests a dramatic and contingent construction of meaning” (Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, Routledge 1990, p. 130) and as “a stylized repetition of acts” (ibid, p. 140). Reflecting on the She-Hulk’s overt sexuality and instantiation of feminine stereotypes (e.g. fashion, flirtation), Robinson asks if John Byrne’s take on the She-Hulk amounts to a “gender performance that is at the margins and is transgressive of societal rules” – that is, if there is any way to understand the She-Hulk as transgendered. Her answer is no less interesting for its being negative:

Although not transgressive in this way, since she is, in fact, defined as heterosexual and female, She-Hulk performs gender precisely as the drag queen does and thus, like that other self-conscious performer, enacts a challenge to the fixed and rigidly anatomical definition of gender at the same time that she seems to confirm it… In encoding herself as so blatantly hetero-female, she shows that, in that identity, she has more in common with the drag queen than with the typical straight female – whoever she is. (2004, p. 102)

The way to understand Robinson’s point, I think, is in terms of a kind of structural tension in the She-Hulk narrative. On the one hand, Robinson is no doubt right that “the invariable focus of the series is the She-Hulk’s body” (p. 102). On the other hand, however, the same transformation that gives the She-Hulk her power, and her powerful body, also transforms her from a “normal” non-super brunette into the iconic Green Giantess (for a more detailed discussion of super-heroine transformations, see this post):

The way to understand Robinson’s point, I think, is in terms of a kind of structural tension in the She-Hulk narrative. On the one hand, Robinson is no doubt right that “the invariable focus of the series is the She-Hulk’s body” (p. 102). On the other hand, however, the same transformation that gives the She-Hulk her power, and her powerful body, also transforms her from a “normal” non-super brunette into the iconic Green Giantess (for a more detailed discussion of super-heroine transformations, see this post):

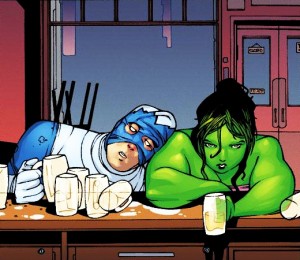

… in a world where, let’s face it, huge bright-green chicks are not much in demand as beauty-contest winners or even Saturday-night dates, She-Hulk wows the men with a body that is the epitome at once of sexiness and super-heroic strength. (Robinson 2004, p. 100)

The question is: How can a character whose appearance is so far removed from traditional stereotypes of female attractiveness turn out to be the most desirable female in the Marvel Universe (as is claimed, for example, multiple times in the letters pages of Byrne’s run on The Sensational She-Hulk)?

Robinson’s answer, then, is this (I think): The She-Hulk’s obsessions with fashion, shopping, daydreaming about Hercules, and meta-fictionally titillating the reader on the pages of The Sensational She-Hulk are (or, at least, can be legitimately interpreted as) a conscious performance of stereotypical femininity (fictionally conscious, and fictionally performed by the She-Hulk; actually conscious, and actually depicted but not performed by Byrne). Although the She-Hulk, unlike Robinson’s imagined drag queen, is biologically female, like the drag queen her physique diverges from the stereotypes associated with “normal” or “desirable” female, and as a result she adopts extreme or exaggerated behaviors associated with feminine desirability in order to be identified (or at least associated) with desirability, heterosexuality, and femininity by the observer/reader. Thus, she is performing femininity as much as the drag queen is, regardless of her biological status.

Robinson’s answer, then, is this (I think): The She-Hulk’s obsessions with fashion, shopping, daydreaming about Hercules, and meta-fictionally titillating the reader on the pages of The Sensational She-Hulk are (or, at least, can be legitimately interpreted as) a conscious performance of stereotypical femininity (fictionally conscious, and fictionally performed by the She-Hulk; actually conscious, and actually depicted but not performed by Byrne). Although the She-Hulk, unlike Robinson’s imagined drag queen, is biologically female, like the drag queen her physique diverges from the stereotypes associated with “normal” or “desirable” female, and as a result she adopts extreme or exaggerated behaviors associated with feminine desirability in order to be identified (or at least associated) with desirability, heterosexuality, and femininity by the observer/reader. Thus, she is performing femininity as much as the drag queen is, regardless of her biological status.

Although Robinson only addresses John Byrne’s run on The Sensational She-Hulk, the issue arises anew in Dan Slott’s more recent run on She-Hulk. This later series focuses on (amongst other things) the fact that Jennifer Walters is much more (hetero-)sexually aggressive when in She-Hulk form than when she is in her “normal” form (for a nice discussion of sexuality in Slott’s run, amongst other things, see this post by Osvaldo Oyola). The standard reading, I think, is that the increased aggressiveness, sexual or otherwise, is a part of the super-heroic transformation, on a par with her immense strength and near-invulnerability. But Robinson’s idea suggests another reading: that the increased aggressiveness is a performance (conscious or not) of hetero-femininity designed to counteract (in some sense) the stereotypically anti-feminine characteristics associated with the transformation (e.g. the physical power, the green skin and hair, the near seven-foot height).

Although Robinson only addresses John Byrne’s run on The Sensational She-Hulk, the issue arises anew in Dan Slott’s more recent run on She-Hulk. This later series focuses on (amongst other things) the fact that Jennifer Walters is much more (hetero-)sexually aggressive when in She-Hulk form than when she is in her “normal” form (for a nice discussion of sexuality in Slott’s run, amongst other things, see this post by Osvaldo Oyola). The standard reading, I think, is that the increased aggressiveness, sexual or otherwise, is a part of the super-heroic transformation, on a par with her immense strength and near-invulnerability. But Robinson’s idea suggests another reading: that the increased aggressiveness is a performance (conscious or not) of hetero-femininity designed to counteract (in some sense) the stereotypically anti-feminine characteristics associated with the transformation (e.g. the physical power, the green skin and hair, the near seven-foot height).

Of course, I am not implying that this reading, based on Robinson’s (admittedly brief) discussion, is the correct, or the only, way to understand the She-Hulk. But I do find the idea that the She-Hulk is somehow performing hetero-femininity in a way that is closer to the performance of the drag queen than to the performance of the typical straight female (if such exists) to be a rather intriguing one. So, to end with a question, in the best PencilPanelPage tradition: How, exactly, does the She-Hulk perform gender?

I think the problem with this reading is that it seems to depend on the idea that femininity is artificial…which is kind of an invidious stereotype. This is a problem with Butler’s gender-as-performance formulation in general; femininity is always the gender performed, whereas masculinity comes across as natural or normal or unmarked. I know you’ve put quotes around “normal,” etc. — but I don’t think that sufficiently addresses the way that this reading assumes that there’s something unfeminine about being 7 foot tall or muscular, and that someone who is those things therefore has to compensate with certain behaviors—as if being interested in fashion, or sex, is some kind of false consciousness, and a less authentic gender expression than not being interested in fashion (or whatever.)

You might be interested in Julia Serano’s critique of Butler, both at the link and in her book-length discussion of prejudice against femininity, Whipping Girl.

In this case I wonder if it might not be more useful to talk about the creative team rather than about She-Hulk’s psychology per se. That is, there are perhaps certain commercial imperatives (real or imagined) for female characters, which perhaps demand that a character like She-Hulk be given balancing feminine characteristics.

This was awesome, thanks for writing it. Really enjoyable read.

But, I do usually agree with most of the objections to Butler’s theory of performativity. Not so much because it’s inaccurate, but because it seems to me an incomplete explanation for the way we develop and experience gender. As Noah points out, if we read as its conclusion the so-called “artificiality of femininity” then it quickly becomes an unsatisfying approach, in my opinion. Gender can be contingent without being “artificial” in its derogatory sense (i.e. fake, pretentious, worthless, shallow).

Does it make any analytical sense to distinguish between the gender you experience for yourself, the gender you signal to others, and the gender other people assign you? Because it seems that Roy (or his sources, maybe) has exposed a chasm between the gender She-Hulk signals to others, and the one she experiences. I think that distinction removes the problematic elements of calling She-Hulk’s femininity artificial because the femininity she broadcasts IS artificial, but the femininity (or the gender, in general) that she actually experiences for herself is a genuinely authentic, true self. In other words, she broadcasts one gender for sociopolitical purposes, and experiences another for personal purposes.

Petar, the problem is, how do we know that there is this disconnect? Why is it assumed that feminine gender performance is not authentic to the self, or is assumed or compromised?

There has been a *lot* of criticism of Caitlyn Jenner’s high-femme gender presentation, for example. Is Jenner overcompensating for being trans and thereby collaborating with the patriarchy? or so different people just feel comfortable with different gender presentations for complicated reasons that aren’t easily reduced to glib psychologizing?

Well, to be clear, if femininity is artificial, then masculinity is as well. One being real and the other fake doesn’t make much sense to me. But that’s more a logical constraint than an argument.

To say that you have one gender and perform another is not necessarily to say that one is fake and the other is real. It’s more that you have two gender identities which serve different purposes and may actually be functionally identical. The gender you present may actually be the gender you feel and identify as, but they are technically distinct identities that just happen to be the same.

The reason I’m worried it doesn’t make sense is because it seems pretty clear that this formulation would have to allow one of these identities to influence the other. For example, if you do present one gender and actually feel another, you would expect these identities to be shaped by one another quite drastically, which means they could be effectively part of one, more holistic identity. The distinction between might not be meaningful. But I don’t it’s necessarily denigrating to femininity, especially because the construct applies to masculinity as well.

don’t think*

And I agree that “glib psychologizing” is inadequate to understand the way gender functions as a part of identity. I don’t think I’m being glib when I say what I said…but I could be wrong.

I’m sure there are many iterations of She-Hulk — most of which I am unfamiliar with — but for many of them I would guess that the answer to the post’s questions above would be that this hero is not really “so far removed from traditional stereotypes of female attractiveness,” except in superficial ways that don’t really translate as “difference” on the page.

To use just one old example that sticks in my memory, She-Hulk (in FF #275) is photographed while sunbathing topless by photographers in helicopters. She tries to get the photographs and destroy the negatives (IIRC), but the photos are published anyway. However, apparently because of some printing snafu, the images are color-corrected so that the She-Hulk appears as a pink-skinned brunette who is of “normal” size (because there is nothing in the images to provide scale).

The issue closes with a joke that the Human Torch will go take the nudie magazine and, I guess, jack off while wearing green-tinted glasses. FLAME ON!! However, what the happy ending (!) of the tale reinforces is that these images of She-Hulk are not all that different from the comic’s “regular” images of the character. For your average magazine reader, She-Hulk is always just a regular-sized sexy woman with a color-cast error. Her greenness, her size, her muscles are always scaled down and superficial, in the same way, I guess, that your average superhero suit is really just a nude with body-paint.

Peter, that’s one thing I loved about Bobillo’s take on She-Hulk (images 1 and 3 above). She’s not just your normal woman scaled up and painted green (as Byrne draws her). Her proportions are incredibly different from other female superheroes.

Proportions being different from most superheroines would make her more like an average woman’s body type, not less, probably…

^ Idiosyncratic reaction amazingly occurs in response to an idiosyncratic character.

But the stereotypical feminine characteristic is sexual passivity, not aggression. (And what’s stereotypically anti-feminine about green skin and hair?)

If “the performance of the typical straight female” doesn’t exist, then She-Hulk can’t be “closer to the performance of the drag queen than to” anything, because the performance of the drag queen is the only coordinate left in the sentence. So Roy T. Cook is saying the performance of the typical straight female does exist, while pretending he isn’t.

It would be useful to have a name for this kind of sentence that qualifies itself out of existence. Escher sentence? (I know that’s already used more broadly.) Or has somebody already come up with something better?

@Noah

Is that Butler (who of course at least nominally considers masculinity a “performance” too)? Or is that Berlatsky setting himself up to argue for a higher general valuation of femininity?

Butler’s fairly complicated (and sometimes opaque). She does consider that no gender has an origin or originaly. However, examples of performative gender in her work tend to be about femininity (drag queens, not drag kings). And (as Julia Serano says at the link) popularizations of her work have been frequently used to tell trans women (especially) that they’re genders are artificial and retrograde.

argh; “originality”

The phrase “gender is a performance” doesn’t appear in Butler, I’m pretty sure. My memory is that the discussion in Gender Trouble is more about originals/copies, the argument being that all gender is a copy (there is no original.) Butler’s also actually talked about some of the problems with her work based on the perspective of trans critics, I believe.

Recently I have been thinking a lot about gender in terms of framing, or rather how the performance of nearly similar acts and qualities get framed as masculine or feminine due to pre-constructed notion of gender. I got to thinking about this after reading Greta Erlich’s “About Men,” wherein she deconstructs the cowboy image to focus in the compassion, sympathy, collective and nurturing aspects of his profession, rather than the rugged loner of the Marlboro Man stereotype.

I am not sure where this is taking me, but I think about things like how physical aggression is considered “masculine,” but not so much to the end of protecting young, for example, where it is still a “mother’s job.” Is it possible that the assignation of gender norms function through a decontextualization and re-framing?

I often think of the example of some years ago where a guy was arrested when a boar he was on sank and he took a life-vest from a little girl to save himself and she drowned. Most of the criticism of his actions in the press was gendered – “He’s not a real man,” “He’s a coward,” “It is a man’s role to sacrifice himself for the weak” etc. . . Yet I can’t help but think that if a woman had done the exact same action the criticism would have also been gendered “Ignoring her motherly instincts,” for example – the exact same act with the same result, but judge as representing an essential gendered quality.

I am not sure where that leaves me in terms of She-Hulk, but Roy’s post and this conversation has definitely inspired me to think about her in terms of the gender frame.

Thanks.

Also, if anyone is interested another She-Hulk themed post of mine also check out “Slut-Shaming She-Hulk.”

Osvaldo, how actions or behaviors are gendered definitely depends on the gender of the person performing them. The inverse is true as well to some degree of course…

Noah, it’s more that Bobillo draws She-Hulk as heavy-shouldered and all-around big as opposed to the usual super heroine with the build of a fashion model.

@Osvaldo Thank you for the link. Suggest a change of title to “Paranoid critic reads pity as self loathing.”

Thank you also for the presumably inadvertent but sublime image of a man riding a sinking boar. (Unfortunately the context ruins it.) (By the way, you’re close but slightly off on the treatment a woman who did the same thing would have gotten. The line would have been: “This happened because feminism has devalued motherhood.”)

@Robert God, those shoulders are beautiful.

Sorry I haven’t responded until now – I pretty much put up the post and then immediately left town to attend the American Society of Aesthetics national meeting.

Anyway, not much to add to what’s already been said. It is worth mentioning regarding Noah’s comment that although the phrase “gender as performance” might not occur explicitly in Butler’s writing, the first quote of the original post is from Butler, not from Robinson (who admits in the book that elsewhere she is also a critic of Butler’s ideas generally). Also, although this was perhaps less than crystal in the original post, I was assuming that the point of Butler (at least, as Robinson is using her work) is that all gender is performative, but that there might be different kinds of performances in different cases. Most importantly, I intended no value judgements regarding better-or-worse, or more-or-less-authentic, kinds of performance.

And to Graham Clark: the parenthetical remark “if such exists” is meant to flag the problematic idea that there is such a thing as a typical (i.e. normal, in a normative sense) straight female. Questioning whether such individuals exist is compatible with observing that there is a kind of performance of femininity that is associated with those that society generally labels as typical straight females (regardless of whether society is right to so label such people). My comparison was meant to be between this sort of performance and the kind of performance of femininity typically associated with drag queens (again, regardless of whether this association is correct). To read it otherwise, and accuse me of a logical error, seems like little more than pointless argumentativeness.

So, more than “pointless argumentativeness,” then? Great!

SHe-Hulk is drawn like that by Bobillo because Jennifer Walters, not She-Hulk, had to go on a Spartan type workout in order to defeat the Champion. Nothing was a challenge as She-Hulk to get stronger, but Jennifer doesn’t need anything beyond what normal people do.

As for She-Hulk’s body/femininity, in one of her comics, its argued or discussed in court that gamma radiation has different effects on the various gamma people. In She-Hulk’s case, its like being a little drunk: sexually aggressive, confident, etc.