I’m teaching “Superhero Comics” this semester, and so I’m once again pulling out Scott McCloud’s abstraction scale:

It begins with a photograph of a face and ends with a face comprised only of an oval, two dots, and a straight line. McCloud calls that last face a “cartoon” and the middle face the standard for “adventure comics,” ie superheroes. All of the faces to the right of the photograph further “abstract [it] through cartooning” which involves “eliminating details” by “focusing on specific details.” Computer programs can do the same kind of stripping down:

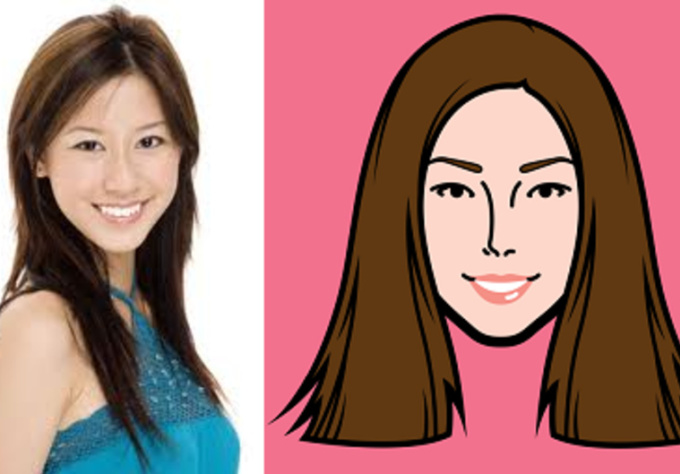

But some “simplification” isn’t so simple. Look at the different between this photograph and its cartoon version.

McCloud’s scale actually combines two kinds simplification. Each step to the right of his spectrum appears simpler because: 1) the image contains fewer lines, and 2) the lines are in themselves less varied. A line becomes smoother by averaging its peaks and lows into a median curve, and so the second kind of simplification is a form of exaggeration. Since exaggeration can extend beyond averaging McCloud’s spectrum actually requires two kinds of abstraction. Each face is altered both in density and in contour quality. Density describes the number of lines; contour quality describes the magnification and compression of line shapes. Abstraction in density reduces the number of lines; abstraction in contour quality warps the line shapes. The less density reduction and the less contour warpage, the more realistic an image appears.

I like McCloud’s five-point scale though, so I’ll offer two of my own.

The Density Scale:

- Opacity: The amount of detail is the same or similar to the amount available in photography.

- Semi-Translucency: The amount of detail falls below photorealism, while the image still suggests photorealistic subject matter.

- Translucency: While reduced well beyond the range of photography, the amount of detail evokes photorealistic subject matter as its source material. This is the standard level of density in superhero comics art.

- Semi-Transparency: The sparsity of detail is a dominating quality of the image, and subject matter can evoke only distantly photographic source material. Semi-Transparency is more common in caricature and cartooning.

- Transparency: The minimum amount of detail required for an image to be understood as representing real-world subject matter.

The Contour Scale:

- Duplication: Line shapes are unaltered for an overall photographic effect. Though naturalistic, reality-duplicating line shapes exceed the norms of superhero art by reproducing too much information.

- Generalization: Line shapes are magnified and/or compressed to medians for an overall flattening effect that conforms to naturalistic expectations. Generalization is the standard level of abstraction for objects in superhero art.

- Idealization: Some line shapes are magnified and/or compressed to medians while others are magnified and/or compressed beyond their medians for an overall idealizing effect that challenges but does not break naturalism. Idealization is the standard level of abstraction for superhero characters.

- Intensification: Line shapes are magnified and/or compressed beyond their medians for an overall exaggerating effect that exceeds naturalistic expectations. If the intensification is explained diegetically, the line shapes are understood to be literal representations of fantastical subject matter within a naturalistic context. If the intensification is not explained diegetically, then the line shapes are understood as stylistic qualities of the image but not literal qualities of the subject matter. Explained or Diegetic Intensification is common for fantastical subject matter in superhero art; unexplained or Non-diegetic Intensification occurs selectively.

- Hyperbole: Line shapes are magnified and/or compressed well beyond medians for an overall cartooning effect that rejects naturalism entirely. Hyperbole is uncommon in superhero art because the stylistic qualities of the image dominate and so prevent a literal understanding of the subject matter. Hyperboles in a naturalistic context are understood metaphorically.

The two scales can also be combined into a Density-Contour Grid:

| 1-5 | 2-5 | 3-5 | 4-5 | 5-5 |

| 1-4 | 2-4 | 3-4 | 4-4 | 5-4 |

| 1-3 | 2-3 | 3-3 | 4-3 | 5-3 |

| 1-2 | 2-2 | 3-2 | 4-2 | 5-2 |

| 1-1 | 2-1 | 3-1 | 4-1 | 5-1 |

Both scales take photorealism as the norm that defines variations.

McCloud’s photographed face is the most realistic because it combines Opacity and Duplication, 1-1 on the grid, demonstrating the highest levels of density and unaltered contour. It’s opposite is not McCloud’s fifth, “cartoon” face, which combines Transparency with Idealization, 5-3; its level of density reduction is the highest and so the least realistic possible, but its contour warpage is moderate and so comparatively realistic. Replace the oval with a circle to form a traditional smiley face, the contour quality would rise to Hyperbole, 5-5, the most abstract and so the least realistic position on the grid.

Cartooning covers a range of grid points, but most cartoons fall between 4-4 and 5-5, both high density reduction and high contour warpage. Charles Schulz’s circle-headed and minimally detailed Charlie Brown is a 5-5.

The characters of Archie Comics are some of the most “realistic” of traditional cartoons at 4-4.

McCloud’s middle, “adventure comics” face combines Translucency and Idealization, 3-3, the center point of the grid and the defining norm of superhero comic art.

Like all grid points, 3-3 allows for a variety of stylistic variation between artists, within a single artist’s work, and even within a single image, but it does provide a starting point for visual analysis by defining areas of basic similarity.

While i really think this is important work (figuring out a proper vocabulary for the processes at work in comics-making and -reading, i mean), i can’t help but feel this is slightly ridiculous; we don’t go around comparing Caravaggio to smileys, do we? These abstractions are decisions any artist worth their salt will be able to make instinctively. Also, putting things on a quantifiable scale that way seems to automatically assume the idea of comics as language, a kind of very elaborate calligraphy. This is debatable. Plus it’s hopelessly anthropocentric, not to mention is biased towards understanding whereas it can be argued that good art does not necessarily aim for clarity.

All engaging points, Ibrahim. Let me try to address some of them.

Caravaggio and smileys are opposites of any abstraction range, so no reason for comparison. But I’m hoping defining the instinctive characteristics will be useful for differentiating images of closer styles.

Writers also do lots of things instinctively; much of my creative writing course is about getting them to do it self-analytically.

I’m not sure why a scale implies a language?

I agree much good art does not aim for clarity, at least not in effect. I like art that feels in some ways inexplicable. Like Sienkiewicz. Though I’m finding the abstraction grid particularly useful in understanding his craft. Perhaps that’s the difference. I’m studying the craft in a work of art, which doesn’t reduce art to craft, it just provides one means of analysis. And I assume all art analysis is biased towards understanding?

And why anthropocentric especially?

As far as slightly ridiculous, well, yes, you’ve got me there. I trade in the slightly ridiculous.

Uh…sorry if that was a bit unreasonable, there. The draughtsman’s fear at seeing his work nakedly dismantled, coldly analyzed?

Actually, are my attempts at naming the various levels (“semi-transparency” etc.) counter-productive? Is that what feels most silly here? Would it better serve simply to have the numbers 1 through 5?

Thanks for the calm reply. I guess i was thinking about being careful to let the comics-specific analysis stop at, say, the narrative building blocks as it were, and look to general art historical studies for the vocabulary used to talk about the drawing or painting- please see my remark about Caravaggio in that context…

The thing is, there is a subtle point at which the analysis of craft becomes the imposition of the reader’s process upon the author’s or artist’s process.

And, yes, come to think of it, the naming of the levels is problematic, because of the implicit comparison to photography, or the equation of realism i should say, to photography. Chuck Close achieves levels of precision that photography can hardly reach, and the idea that photography presents any kind of realism is quite suspect in a way. Plus there is also the character of the lines to be considered. The line density of a Holbein or Klimt drawing can be quite similar to a Georg Grosz one, yet the effect differs as night from day. Jeffrey Catherine Jones’s line work can be transparent while fully referencing its original photographic source.

I think analysis is almost always an imposition. I think the term means literally to dissolve, to break apart. But of course there are degrees. And your point about line thickness is great: a drawn line can duplicate the contour of a retinally perceived line while also radically altering it. And of course photography is not realism. I think Douglas Wolk in Reading Comics emphasizes “retinal,” which better distinguishes the visual approach: to what degree is the artist creating an image that imitates our perceptions of real-world subjects?

It’s ‘to cut apart’ unless my knowledge of the dead languages betrays me…

Cutting apart does not change the constituent parts, it lays them bare; imposition, however, obscures the parts in favour of an interpretation of them.

If we go with ‘retinal,’ how far are we from ‘neural’ ?

Asking in earnest, not just to be annoying, i assure you…

Is there a survey on which type of terminology artists themselves would be comfortable with?

I suppose retinal in fact always IS neural, since it’s the perception, not the apparatus of perception, that matters most.

First, I appreciate the level of thought going into this effort, and I’m all for developing a shared vocabulary for discussing comic art. I’m particularly behind any effort that includes prior scholarship and remains open to suggestions. However, I think there’s a real issue with the scale as developed here. First, it uses photography as a baseline for realism, which as Ibrahim observes isn’t simply a reproduction of reality, but also an interpretation and abstraction of reality. As a result, it puts the critic in the position of interpreting one representational system according to the standards of another. I’d argue that this is a theoretical problem, though, which means its only a problem if your theory of representation is at odds with the underlying theory of the one outlined here. The second issue has to do with the interpretive process itself. How can I be sure that two critics will agree on the level of abstraction, especially since what constitutes an abstraction is bound to a particular visual culture. For example, readers of superhero comics sometimes reject manga because the art lacks realism when, in fact, your average superhero comic artist takes just as many representational liberties. Basically, this is an issue of inter-rater reliability. For a system like the one proposed to be productive it needs to be reliable when deployed by a variety of readers who have minimal coaching. Based on what I’ve read here, I’m skeptical that this system would meet that standard.

This is the Internet, so it’s past time for someone with no qualifications whatsoever to offer an opinion: What Chris is building is not a language, but a taxonomy. His methods of analysis could eventually be robust enough to do a “line art genome project,” a la the music one that my phone apps use to pick music for me. That works imperfectly, because there is still so much variation even at the same point within the multi-dimensional scale, but mostly effectively.

Of course, McCloud’s point is that all levels of abstraction are useful, but they have different strengths and weaknesses. Peanuts would not be as funny or as powerful at a higher level of realism, in my opinion. So different methods are for different purposes.

One more thought — the relationship between density and realism is not always direct. Superman looks happy and friendly and powerful in the John Byrne image above — i.e., like Superman — but a less detailed Mike Allred version might be more realistic, because it would show less of the exaggerated musculature that Byrne magically makes visible through the suit. I think this is an example of Nate’s point comparing manga and Western superhero art.

Nate, your and Ibrahim’s critique about photography and realism is essential. I need to rework this to eliminate or at least acknowledge the conceptual bias. I’m hoping something along the lines of “retinal perception” may do that.

Your second point is trickier, and actually what I’m trying to get at:

“How can I be sure that two critics will agree on the level of abstraction, especially since what constitutes an abstraction is bound to a particular visual culture. For example, readers of superhero comics sometimes reject manga because the art lacks realism when, in fact, your average superhero comic artist takes just as many representational liberties.”

My goal is to eliminate the use of the word “realism” and replace it with descriptions that two critics in fact could agree on. Instead of calling either Manga or superhero comics figures realistic or unrealistic, we can describe how many lines the image contains (density) and how the shapes of those lines conform to our retinal expectations of a human figure (contour). Superhero faces I think tend toward 3-3 on my scale; and Manga faces 4-4.

John provides another example. Neither the Byrne nor Allred Superman figures are “realistic.” Byrne’s contains more lines/details and so has greater density, but the contours of those lines are highly idealized (so what I’m calling 3-3 or 2-3), while Allred has fewer lines (so lower density), but probably about the same level of idealization as far as line shapes (so 3-3 or 4-3).

This is an interesting taxonomy, Chris — god knows I love a taxonomic table. As with your discussion of closure/transitions/whatevs, I can’t help feeling that these kinds of issues must have already been (partly) worked through somewhere other than comics studies, and that you might be able to avail yourself of some of their machinery.

…maybe in the cognitive science of vision, or, I don’t know, some kind of intersection of information theory and the computer science of visual representation? Those seem like the kind of areas that might have already had to grapple with what it means to “abstract” an image, and had to do it in a way that would speak to some of Nate’s concerns about objectivity.

I’m not sure what claims about density buys us, and I’m not sure how to quantify idealism (which is a culturally loaded concept).

For me, the issue less about objectivity than it is about utility. That is, what kinds of questions does a taxonomy like the one above allow us to answer. If the taxonomy raises more questions than it answers, that’s a problem. Of course, this is a work in progress, so I’m not going to discount the effort.

As to Jones’s point about looking at cognitive science beyond comics studies, there’s a fairly robust literature in cognitive film studies, complete with taxonomies. I’m not sure how well these insights will transfer, as they’re fairly medium specific. But they might be a good place to start.

Utility is the big issue. And, yes, if someone else has done this better in another field which can be transferred to comics, I want to go there. I’ll look into cognitive film studies next.

Chris, when i called the method hopelessly antropocentric, it was because the example shown perhaps gives a false idea of its application: it is far easier to name a level of abstraction when looking at a face than looking at a leaf or a stone. At the same time, it is difficult to unsee the mental accretions that attach themselves to an abstraction of a face. I was imagining the method to come up short when faced with anything other than a face. So, it was my own reasoning that was anthropocentric; however i do imagine the problem posed above exists.

Thanks, Ibrahim, that makes perfect sense now.

Wow, this is interesting. It’s kinda crystalized thoughts I’ve had recently.

Looking at most superhero comics, I came to the conclusion that todays standard (going back about 15 years it seems) was a simplified photo realism. It’s photorealism, based heavily on literal photos, but with very few lines. It’s extremely boring.

Growing up in the 90’s, I loved guys like Todd McFarlane and Romita Junior and Liefeld who made exaggerated, cartoony, characters- and with lots of (unrealistic)detail! Not super deformed type exaggeration to be sure, its all relative- but those guys relied minimally on photo reference- if at all.

It seemed that comics criticism never touched on this seemingly obvious, but- as demonstrated here, nuanced observation; that or I haven’t noticed till now.

Thanks, Spencer. That was my hope! I have a few art majors in my comics course this semester, and hoping my grid proves as useful to them.

Your scale is all good and well, but you don’t touch my trouble with McCloud’s claim about identification. How comes that millions of movie or TV spectators can identify easily with photorealistic representations (moreso, because of movements and sounds), while comics reader’s identification relies on simplification?

You’re in good company, Joachim. I was just reading a couple of comics scholars who dismiss Cloud’s claim too. I think he’s actually talking about two different things, one true, one very unclear.

When you look at the male icon on a Men’s Room door, the figure is as simplified as possible. The head consists of one line only (on my scale that’s a 5-5, the lowest density of detail combined with the highest level of contour warping). And it is true, when I look at that icon I understand it to represent all males, and so to that degree I “identify” with it. Where, on the other extreme, a photograph of one specific man would be “identifiable” to only that one person.

But it’s highly unclear to me how or even if that kind of identification relates to reader empathy for a drawn character. Regardless of a character’s level of abstraction, I do not “identify” with that character as if its image somehow includes me as part of what it is representing. That actually sounds a little insane–that I could somehow believe a drawing of circle-headed Charlie Brown in some way was a drawing of myself. But at the same time, I can feel an emotional connection with the character of Charlie Brown.

So “identification” has two different definitions, and McCloud combines them as so comes up with a highly questionable claim.

“And it is true, when I look at that icon I understand it to represent all males, and so to that degree I “identify” with it.”

Is that because of the level of abstraction, though? Or is it because you’ve learned that that’s what it means?

“Is that because of the level of abstraction, though? Or is it because you’ve learned that that’s what it means?”

This is key… Most comic art isn’t about representation or mimesis in the classical sense. Rather, it’s about manipulating signifiers. That is, if you’re drawing the Fantastic Four you’re not really aiming to create a plausible facsimile of reality so much as a reasonable iteration of Kirby. With this in mind, it’s hard for me to take seriously Cloud’s claims about identification. However, it’s also what leads me to wonder whether the scale isn’t proceeding from a faulty premise. Namely, that the cognitive dimensions of comic art turn on questions about visual fidelity as measured in the quantity and quality of line.