Daniel Clowes’ latest book, Patience, came out in Danish (and a few other languages, as far as I know) just before Christmas last year, as part of an effort by the publisher, Fantagraphics, to jump start international sales and avoid having them cannibalized by the American edition. Here’s a brief first take in anticipation of the discussion the book will hopefully elicit upon its official American release next month.

Patience is a love story dressed up as equal parts social realism and time travel adventure. It is also Clowes’ first unequivocally romantic work. Its protagonist, the self-described loser Jack Barlow, and his beloved wife Patience are expecting their first child. But one day he comes home to find her murdered on their living room floor. He spends the next seventeen years monomaniacally—and in vain—trying to find the murderer until, suddenly, he is given the chance to travel back in time, save Patience and make sure their child is born.

It does not quite go as planned. Jack is impulsive and possessed of a real temper, which time and again sends events careening out of control, crisscrossing the timeline. It is perhaps Clowes’ most entertaining work since the his early humor pieces, a real page turner with an unpredictably spontaneous, but predictably funny character at its center. Much like Clowes’ previous protagonist Wilson (2010), in fact—another self-sufficient yet hapless sap of the kind he so excels at.

Jack is in many ways a fleshed-out version of the censorious, self-delusional Wilson, who also seeks to restore his broken family. In spite of his many shortcomings, it was hard not to like him, and that goes double for Jack even though he is even more of a dubious acquaintance. Where Wilson studied rain drops, Jack stares at the wall, blinds drawn. And whether we are talking 2013 or 1985, the wall is full of holes—the result of off-panel tantrums or panic attacks, one senses.

Jack’s thought processes, ways or reasoning and, at times, actions border on the sociopathic, which calls to mind Clowes’ perhaps most disturbing character, the borderline superhero Andy from his masterful The Death Ray (2004), who lucidly assumed the role as supreme arbiter over other people’s life.

Yet we still like Jack because he is so unequivocally driven by love—a love which here literally transcends space and time. Actually, the time traveling brings out the oedipal undertones of it, not least clearly at the moment when he finds himself in front of his fatherless childhood home. The riddle of the Sphinx is here a murder mystery the solution to which depends on whether Jack is fundamentally subject to the same crushing predestination that brought King Oedipus low. Can we change the future?

Clowes transposes this struggle against determinism to Patience’s efforts to break with the social conditioning she has inherited as the child of a broken working class home in the Midwest. A large part of the story takes place in the small town in which she grew up, during the years immediately before she met Jack. Patience sometimes assumes the role of second narrator and her portrayal is the heart of the story. She is the whole person Jack aspires to be.

These passages are exemplary of how subtly and bracingly Clowes describes crushing social circumstances and thus recall earlier signature works such as the ensemble piece Ice Haven (2001), which also took place in a small American town, and the more intimate post-school comedy Ghost World (1997), which was fundamentally about transcending expectations.

Clowes’ well-known misanthropy is remarkable subdued in this story—even his Kubrick-like irony is downplayed. Only in the rather uninventive description of Jacks future in the year 2029 does his disinterested line come up short and resort to camp.

Clowes’ cartooning is here more nonchalant than usual. One gets the sense that he does not mind if his drawing comes across as inelegant. For the most part, however, this seems an entirely natural choice for this particular story—on paper his most fantastic. And even though Clowes is not possessed of the uncanny design genius of his paragon Steve Ditko, his surreal interludes in which he invokes the heady abstraction of prime Doctor Strange as well as the bizarrely loaded symbolism of Ditko’s objectivist comics seem perfectly calibrated and emotionally earned in this story about the order of things.

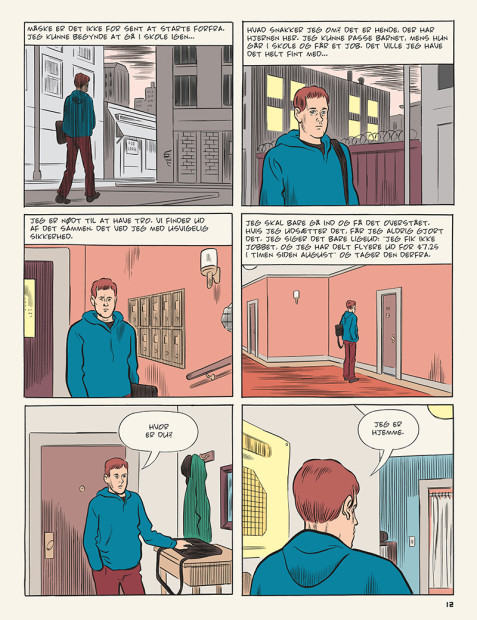

Matthias, I’m curious how the 3×2 grid you include above might relate to the question of “crushing predestination.” Reading that page alone suggests that time is unalterable–because the layout predetermines the position and shape of each panel in advance. Watchmen creates a similar effect (suggestive of Dr. Manhattan’s perspective) through the repetition of 3×3 grids (or implied 3x3s since every variation either combines panels or divides them uniformly).

Good to see you around again, Matthias!

Thanks Domingos! It’s good to be back. I hope I’ll be able to contribute a little more than a short piece every three years, but eh, let’s say it’s been difficult…

Chris, thanks for commenting! While there is a certain confluence of ideas vis-à-vis Watchmen, the formal approach is quite different. The grid on the page reproduced above is not necessarily representative of the book as a whole — Clowes varies his page layout quite a bit through the book, though there are times when he breaks the grid entirely, and those are thematically, as well as narratively, important.

In “The Death Ray” he mimicked the various commercial comics formats: Sunday page, comic book page, etc… But I never practiced one of my favorite sports which is to link formal devices with content to see how gratuitous, or not, the former are.

Yeah, Clowes has been playing with that device for some years now, most notably in Ice Haven and Wilson. He has abandoned it for Patience, however, which is a good choice. While it worked extremely well, also conceptually, for those books, it wouldn’t have worked here. The two most formally challenging things he does in this book is visualising the future — always difficult in a basically realistic work — at which I think he to an extent fails, resorting to eye-winking camp, and those Ditko-inflected breakdowns of the page, which he doesn’t do as well as Ditko, but which I think nevertheless pack a punch through their contrast to the main, rather realistically rendered sections of the book as well as what they imply about its underlying thematic and structural concerns.