I published a piece at Playboy yesterday about the new revelation that Captain America is part of Hydra. I mostly talked about Truth: Red, White, and Black, the miniseries by Robert Morales and Kyle Baker, which imagines the supersoldier serum tested on a group of black soldiers in a Tuskegee-like experiment.

Anyway; one thing I wanted to get into the piece but couldn’t quite fit was a discussion of this sequence.

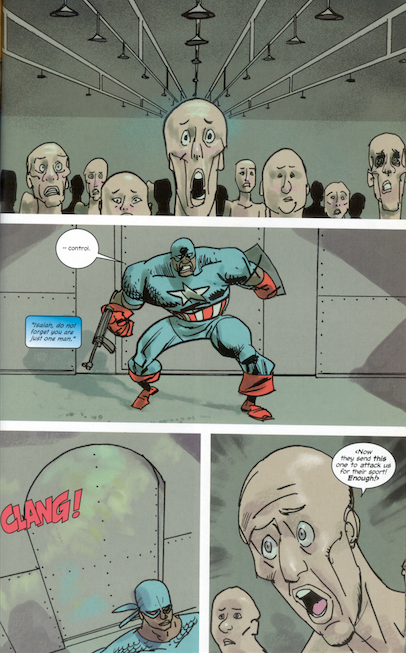

Isaiah Bradley, the one survivor of the supersoldier experiment, has been sent on a suicide mission in Germany. In the course of his effort to destroy the Nazi supersoldier project, he attempts to rescue Jews from a gas chamber. They don’t realize he’s trying to rescue them, though. In fact, they think the Nazis have sent him to rape them. Their confusion, it is implied, is caused by the fact that he is black. In short, the comic presents Holocaust victims, at the moment of their death, as racists.

This is probably the single most shocking moment in a comic that is full, front to back, with shocking moments. The scene is obviously played for gothic horror; the naked, emaciated women swarming over Bradley, a zombie tide of death. But the gothic is here, specifically, a white gothic. The Jewish women, moments away from becoming victims of racist murder, find a final, horrible solidarity in anti-black racism. They can’t see Bradley as a savior because of their racial preconceptions, and so he can’t save them from their racist murderers.

This scene obviously isn’t true; nothing even remotely like this ever happened. Black people were depicted as rapists by German propaganda though—and in Maus, Art Spiegleman shows his father, a concentration camp survivor, as harboring racist animosity towards black people. It certainly seems possible, and in fact likely, that some of those who died in the concentration camps believed that black people were inferior and subhuman—just as the Germans believed Jews were inferior and subhuman.

You could see Truth as a vision of reconciliation, or solidarity, between black people and white Jewish people. Captain America was created by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, both Jews, and he here becomes a symbol of black pride, and of American blackness. “Isaiah” could for that matter be a Jewish name; Bradley is, in effect, both Jewish and black, deliberately connecting the persecution, and the heroism, of both identities.

The scene in the gas chamber points to a less cheerful reading, though. The experience of oppression doesn’t have to unite the oppressed. In some cases, instead, the fear of oppression, or the brutal, intimate, immediate, reality of oppression, can lead to more racism, more hatred, and more violence. Morales and Baker depict Jews, at the moment of their genocide, choosing, in fear and horror, to be white. That doesn’t have to be the Truth. But still, it’s a choice that is a bit too familiar for comfort.

Man I really don’t know how people could ignore or talk down this miniseries. It’s endlessly uncompromising in all the ways it’s been discussed by yourself

There’s a very similar line in Attack on Titan (the anime), where a high-ranking commander tells Eren Jaeger, the hero, a story, where he says that before the Titans came to devour humankind, humans fought endless wars between themselves, and thought that if a non-human enemy came to threaten all mankind, they would unite against it. That does not even remotely happen in Attack on Titan. Ozymandias’ giant alien squid-monster falls from the sky, and their reaction is to punch and stab each other over the crumbs leftover. It’s a pretty grim vision of suffering and oppression, that seems to gel with your less optimistic reading of Truth.

Donovan, the end with Steve Rogers is really a problem; it almost literally comes out and says, “there are good white people! we promise!” So, there are flaws. But it’s very impressive in many ways, there’s no doubt.

Noah:

‘Donovan, the end with Steve Rogers is really a problem; it almost literally comes out and says, “there are good white people! we promise!”

But, Noah — there really are ‘good white people.’

Look, you’re White. Do you consider yourself evil by definition of your skin color?

That coda of The Truth is best interpreted as Steve Rogers acknowledging his African-American predecessor as the ttrue, original Captain America.

BTW, scripter Rags Morales and artist Kyle Baker were both Black men. And the surviving Captain America creator, Joe Simon, enthusiastically endorsed The Truth‘s retconning.

The existence or nonexistence of good white people is generally less important than racist structures which give white people power, is kind of the point. And one racist structure is the narrative dictat that white people always have to swoop in to save the day and assure us that the goodness of white people, rather than the structure of racism, is the most salient point.

That’s cool that Joe Simon liked Truth. I’m not sure whether Morales identified as black or not, honestly.

Within the context of the comic as written, at least as I understand it, Rogers is still the original captain america. Tests on the black soldiers are done after the original scientist is killed, and after steve has become Captain America. Rogers is supposed to join Bradley on the mission, but is unable to do so because he’s killed at the same time (to be preserved in ice, etce. etc.)

Good intentions count for something, surely?

A bagful of good intentions and a dollar will buy you a dollar’s worth of candy.