It is rare to see an adaptation come under attack from followers of the original for being too faithful. Dramatizers regularly compress and invent for what they hope will be the strongest statement in another medium, then defend their interpretation as being in the spirit, if not the letter, of the source. The devotees’ essential reply is that the failure to respect detail, or honor the letter, lost the spirit, leaving some creature that had no right to go out under the same name. Did the adapters think they knew better than the writer?

That secular attachment is a pale, fleeting image of what the Bible can mean for readers, yet here we have seen some furious attacks on a groundbreakingly faithful treatment. People with long relationships to the original are insisting that the Book of Genesis demanded an interpretive, even editorializing approach. According to one critic, the Bible is right there if anybody wants to read it. R. Crumb’s The Book of Genesis Illustrated needed to reshape and select its material. The artist should have pushed his opinions in front, even lampooned it because that’s what he does, and instead gave us a boring, stodgy, completely unnecessary work that never, ever should have been made. (Though why is the mirror-universe review so easy to write: “Had Crumb been able to restrain his clowning urges, he might have learned a ‘“not-so-” secret’ that we who know the Bible have known for years of watching these acts go by: nothing could have been more shocking than a straight adaptation.”)

Given the deaf ears turned to it in these discussions- the point is denied until corrected, then was never at issue and isn’t important anyway- the pioneering nature of a comprehensive illumination bears repeating up front. As Crumb told Comic Art Magazine at the outset of the job,

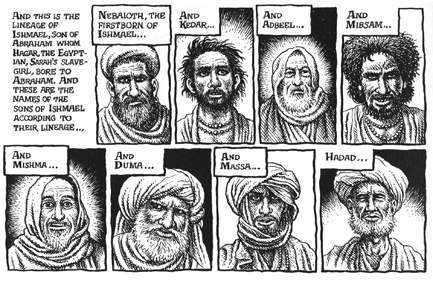

“I’m going to be doing all fifty chapters of Genesis, including every word. Straight from the original- I’m not leaving out anything… you’ve got to do an extremely close reading. It’s really interesting and full of surprises, what is actually in there when you read it closely. And, you know, believers tend to gloss over the stuff that makes them uncomfortable or that they don’t get. But it’s in there, you know, so it’s going to be illustrated, so…”

But such a believer is not the serious student of theology, who wrestles with these problems until they grant him understanding. Crumb prepared for heat from religious fundamentalists, who claim the Bible as literally true history, instruction, prediction, and absolutely present a major cultural force that would be foolish to ignore (“If I’m going to be doing this and don’t want some Christian fanatics to kill me, I’ve got to say ‘Look, it’s all in there, I didn’t change a single word, it’s in your holy book…’ so we’ll see if they want to kill me or not,”) but this left his flank open to condescension from those who are dedicated to exploring its deeper meanings. Another commenter:

“Part of the problem I had… [was] the overly literal interpretation and complete lack of insight about the actual ideas underlying Genesis. Virtually all scholars, rabbis, clergy etc. in the modern day, even those with more fundamentalist leanings, use the bible as a starting point to interpret the metaphors and stories and apply them to the modern day… Yet I would suspect that very few, if any, clergy believe in the stories as literal, historical facts.

“Thus, the depictions of God as an old man, the creation story, etc… represent a very childish understanding of Genesis. That would be fine if this were a children’s book, but the problem is that by presenting the entirety of the dense text… no child will be able to penetrate this book either.”

We can all understand how a treatment could cling to the letter, lose the spirit, and end up flat. From Ng Suat Tong’s essay, posted here on July 14, a reader might get the impression that Crumb has given us a soulless, mechanical transcription that recycles Sunday-school figures (a white beard, a cuddly Garden of Eden) and only superficially engages the work it was based on. It’s easy to take Suat’s accusations of a lack of intellectual and spiritual involvement in Genesis in a still essentially worldly sense, and a genially agnostic member of the public might see no harm in letting the religious and literary meanings blend. But his fault-finding refers to a lack of dedicated application in a religious framework that none of us should wish to see confused with the “soft” intellectual and spiritual experience of a great book.

(I gave a detailed response to his points in the comments thread for his essay, which was collected here.)

The overriding problem is his persistent call for Crumb to do something with his adaptation that he’s not trying to do. Suat’s characteristic complaint is that Crumb fails to explicitly incorporate centuries of Biblical scholarship, for which the evident rejoinder is that these were not books he chose to adapt. As just one example,

“In response to Genesis 3:15… we get a somewhat cursorily drawn snake wriggling away. It is common knowledge that Christians look upon these verses as the protoevangelium (for example, some church fathers saw the ‘woman’ here as the virgin Mary and the ‘seed’ as representing the church and/or Christ in particular) while Jewish commentators sometimes view the ‘seed’ as a metaphor for humankind. There is little evidence of a response to these or any other interpretations here.“

These objections are so consistent they have an emergent property as a fairly clear request for a comic that would travel through Genesis (if it got out of Eden) with a chemistry of text and symbolic imagery, discussing the interpretations of the ages. Perhaps some cartoonist out there is looking for a project. A highly routine style of Biblical adaptation that tricks out the narrative with new scenes and dialogue could also work in some scholarship (again, we can hear the response: “Crumb’s is the latest in a long line of reworkings of the Bible,”) but this was not his project either. As he told The Paris Review,

“In all the comic-book versions I was able to find, they just made up dialogue, pages of it that are not in the Bible. I was reading this one thing and I thought- did I miss this? And I went back and checked against the text and it’s not in there. And they claim to be honoring the word of God, and that the Bible is a sacred text… the most significant thing is actually illustrating everything that’s in there. That’s the most significant contribution I made. It brings everything out.”