(Some reflections on found art and the end of the Comics Buyer’s Guide)

Of all the things I discovered in the pages of the Comics Buyer’s Guide (CBG) during the 1980s and early 1990s, I still cherish Matt Levin’s Walking Man Comics, a series of minicomics the artist began producing in 1988. I first read Levin’s work, which he creates with a variety of rubber stamps, in the anthology Oh, Comics! The Official Comic of the Mid-Ohio Con (1988). I received a copy of Oh, Comics! from my friend S. Minstrel, a San Antonio-based zine maker who’d read a review of one my minicomics in CBG’s small press column. Without CBG, I would never have begun my correspondence with Minstrel and the other zine makers in his circle, and I would never have discovered Matt Levin’s work, which remains a vital and idiosyncratic contribution to the art and history of the minicomic.

I began thinking again of Walking Man Comics while reading the many online essays and blog postings about the demise of CBG, which will come to an end with issue #1699 in March. Other writers have already told the magazine’s history in far more detail than I could offer; see, for example, pieces by Rich Johnston, John Jackson Miller, long-time CBG columnist and comics writer Tony Isabella, and, of course, CBG editor Maggie Thompson . I have decided, then, to offer a short reminiscence of the magazine in the form of a review of Levin’s work which, like the other zines and minicomics I discovered in the pages of CBG, prepared me for other works on the fringes of American popular culture which I now adore as a adult.

While those who enjoy John Porcellino’s King-Cat Comics and Carrie McNinch’s You Don’t Get There From Here will no doubt appreciate the do-it-yourself minimalism of Walking Man Comics, Levin also has affinities with New York City-based photographer and playwright Kelly Copper. Her work with Pavol Liska and the Nature Theater of Oklahoma seeks to reassemble the fragments of the everyday—transcripts of mundane telephone conversations, for example—into epic works like Life and Times: Episodes 1—4, which has been popular in Europe and enjoyed a successful January 2013 run as part of the Under the Radar Festival at The Public Theater.

Masterpieces are beautiful, too, in a spectacular, Technicolor fashion. But sometimes small, quiet works of art—covered in the smudges and fingerprints of their makers—are more lasting and precious. I suspect if I had not read Walking Man Comics in 1988 I would not have fallen in love with Copper’s photographs in the late 1990s.

These notes, then, began as a documentary of the years I spent reading CBG—memories of Don Thompson’s reviews; Cat Yronwode’s “Fit to Print,” which featured a column heading drawn by a different amateur artist each week (including, in 1987 or so, ones from me and my younger sister Alison); Mark Martin’s “20 Nude Dancers 20” cartoons. I also recall the letters from firebrand science fiction legend Harlan Ellison and pioneer comics scholar M. Thomas Inge. When I needed information on a project on comics for one of my high school Spanish classes, I wrote a letter to CBG’s “Oh, So?” column asking for help and received a detailed, encouraging letter from Inge and a package of Condorito comics from a new pen pal in New York City. I once received a phone call from Ellison regarding a letter I’d written on comics and censorship, but that is a story perhaps best left for another essay.

Writing a personal history of my relationship with CBG, I realized, would be impossible. When I finished a first draft, I found myself with a shopping list of memories meaningful only to me. I had fallen into the trap of nostalgia Alan Moore describes in his early 1980s Marvelman proposal: “Nostalgia, if handled wrong, can prove to be nothing better than sloppy and mawkish crap. In my opinion, the central appeal of nostalgia is that all this stuff in the past has gone. It’s finished. We’ll never see it again…and this is where the incredible poignance of nostalgia comes from” (Moore 24).

How ironic, then, that, as a means of commemorating the passing of CBG, I should write instead about a series of minicomics which seek to evoke wistful feelings of some lost, idyllic world. Like Copper’s photographs of stills from abandoned home movies, however, Walking Man Comics also seeks to discover an otherwise unspoken or unrealized present. As Levin writes on the cover of a Walking Man Sampler from 2002, “I like / layout design, / words, / simplicity— / I like rubberstamps’ ability to mimic nature’s multiplicity…”

Levin continues to produce Walking Man Comics, which he describes on his Facebook page as “12-page mini-comics” filled with “rubber-stamp images combined with photographs and line-work in imaginative page layouts.” In addition to “Imagination, brevity, elegance and wit,” Levin’s goals include “the promotion of mini-comics as an affordable, pocket-sized means of personal communication available to everyone regardless of age, education, and ‘professional ability,’ dedicated to the principle that one’s level of drawing ability should never discourage creators.”

Both Levin’s comics and Copper’s photographs might be understood as examples of “found art.” Frank Bramlett has written about the relationship between found art and comics in a post to Pencil, Panel, Page in which he challenges us to open our eyes to the neglected visual narratives which surround us: “Do found comics qualify as a ‘legitimate’ (!?) genre, arising out of occasional and/or accidental use of comics conventions? If so, where do you see found comics?” With Bramlett’s questions in mind, we might read the following detail from Copper’s Untitled as a sequential narrative—a repetitive depiction of a quiet, intimate moment.

In her 2002 exhibit reel, Copper included a series of photographs based on images from abandoned home movies she had found at New York City flea markets and antique stores. Untitled is an Andy Warhol-like grid featuring a blond, middle-aged woman’s face. She is wearing sunglasses with cat’s-eye rims. There is an expanse of sky behind her—first blue, then white. The whiteness then meets a rim of trees.

The woman laughs, turns her head, looks over her right shoulder, stares at us, invites us to laugh with her. We will never know her name. Her pale shoulders shrug, then straighten again:

Fig. 1: A detail from Kelly Copper’s Untitled (2002), an image from her 2002 show at An American Space Gallery in NYC. Image courtesy of Kelly Copper.

Copper took each portrait from a film which presumably tells the story of this woman’s vacation. Copper projected the film on the blank, white wall of her apartment, froze the images, and then photographed those still figures. What pleasure is there in these forgotten, neglected movies, blurry records of family vacations, 4th of July parades, high school graduations, and gaudy senior proms?

As Copper explains in a 2006/2007 interview with Amber Reed, home movies have a seductive power unlike other forms of cinema. Watching these old films, Copper found a new confidence in her role as an artist, a sense of fun which “short-circuits the critical voice that says, ‘oh, that’s really dumb,’ because ultimately I’m just playing. And I think that’s also been part of the aesthetic for the Nature Theater of Oklahoma—how do you get back to this feeling of theater as play?” (Copper qtd. in Reed).

Like the anonymous subject of Untitled, Copper is at play in a world notable for its simplicity—the sunlight, blue sky, and green trees of a family vacation. Of course, it is a point in time which did not exist, at least not as figured in this image. No lived moments have such clarity. Only the eye of the artist can record such an image. While joy such as this might be fleeting, the few minutes this woman spent with a Super-8 camera over half a century ago have made her ageless and eternal.

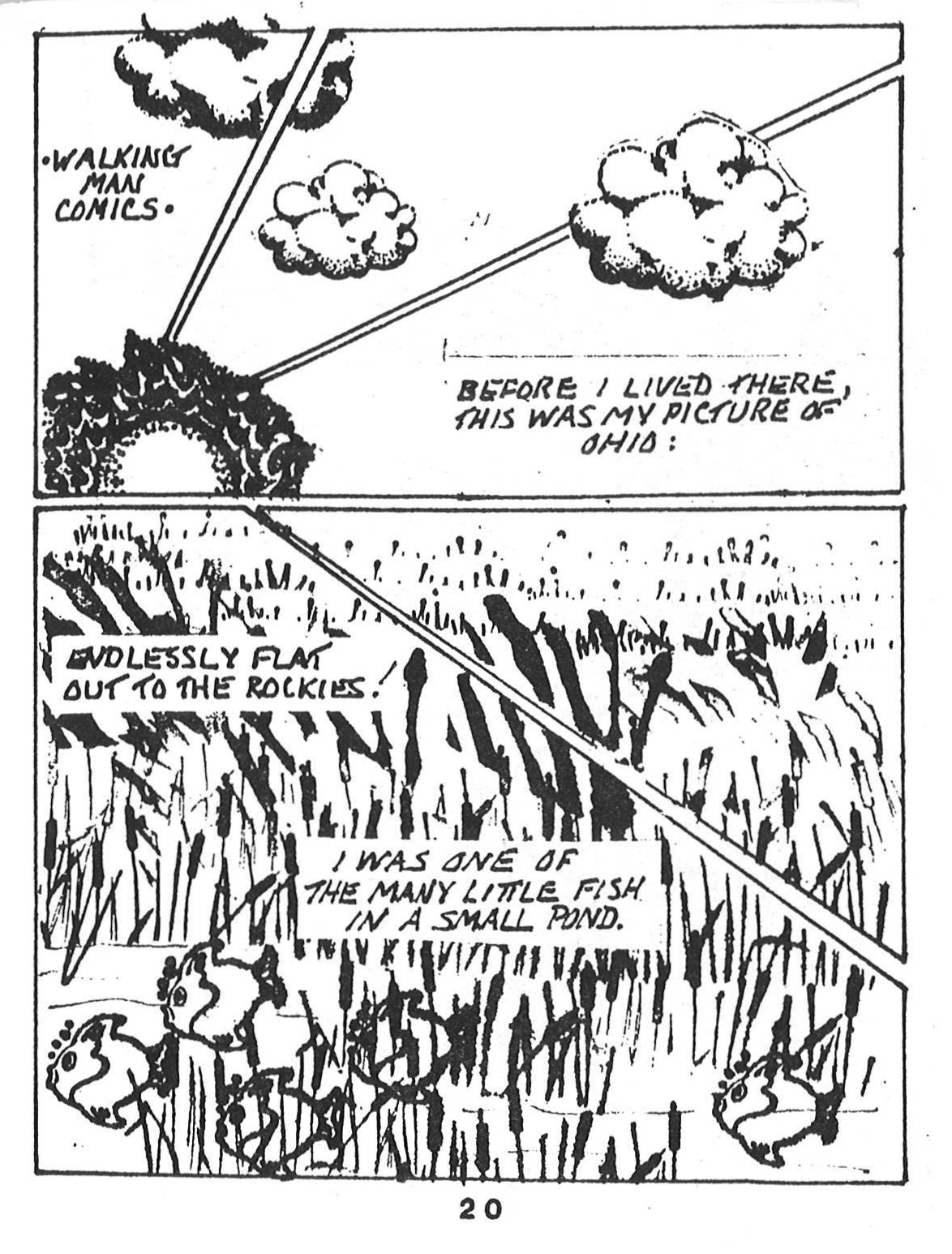

Is a rubber stamp itself a kind of found art like these stills? Or is it a tool like a pen or a brush? In his short piece in Oh, Comics!, Levin uses rubber stamps of clouds, a sun, fish, cattails, and trees. Like Copper, he has recorded for us these quotidian moments:

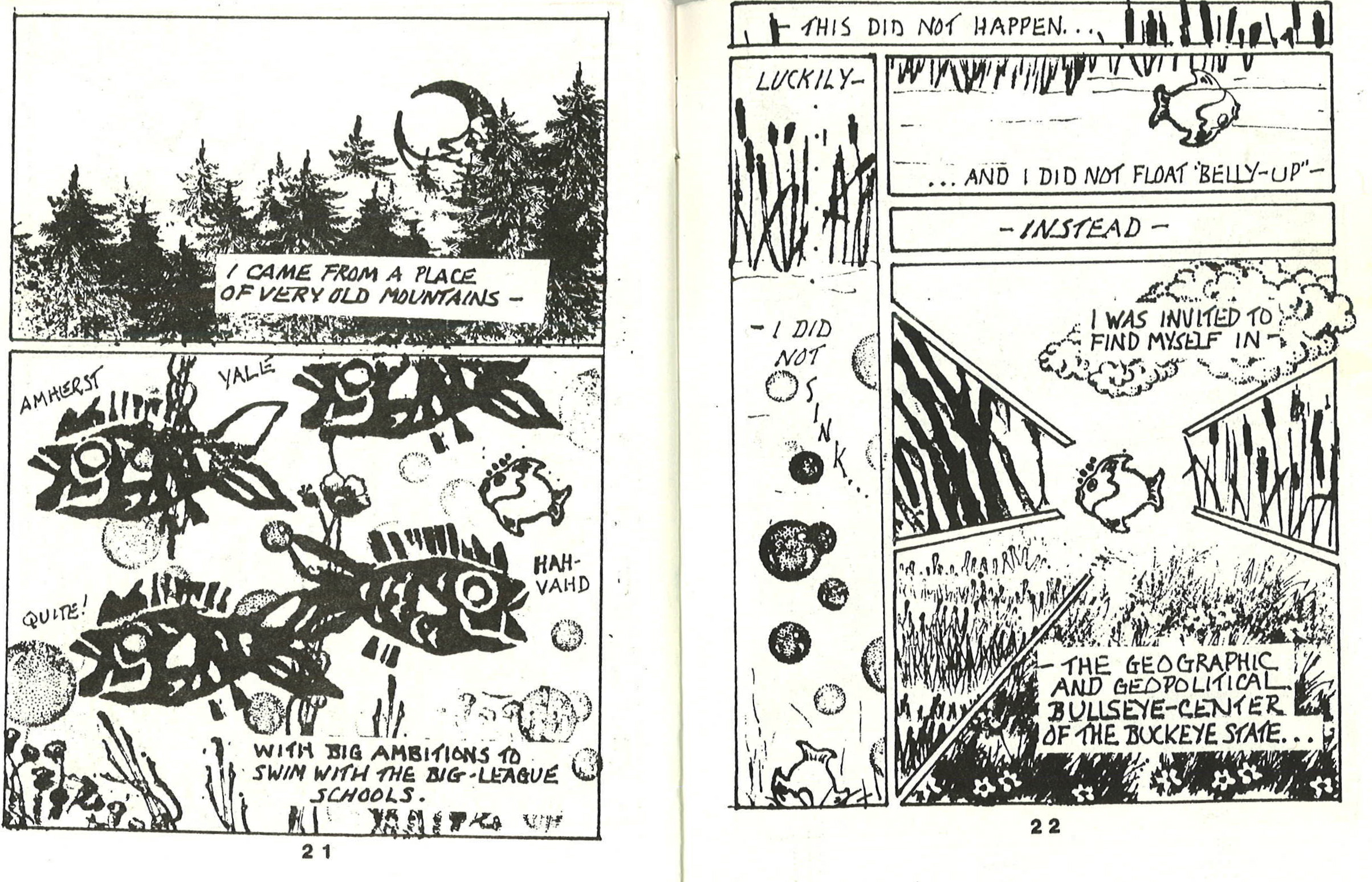

Fig. 2: The first page of a Walking Man Comics story in the anthology Oh, Comics! The Official Comics of the Mid-Ohio Con (No. 1, 1988). The following pages are also from Levin’s story in Oh, Comics!

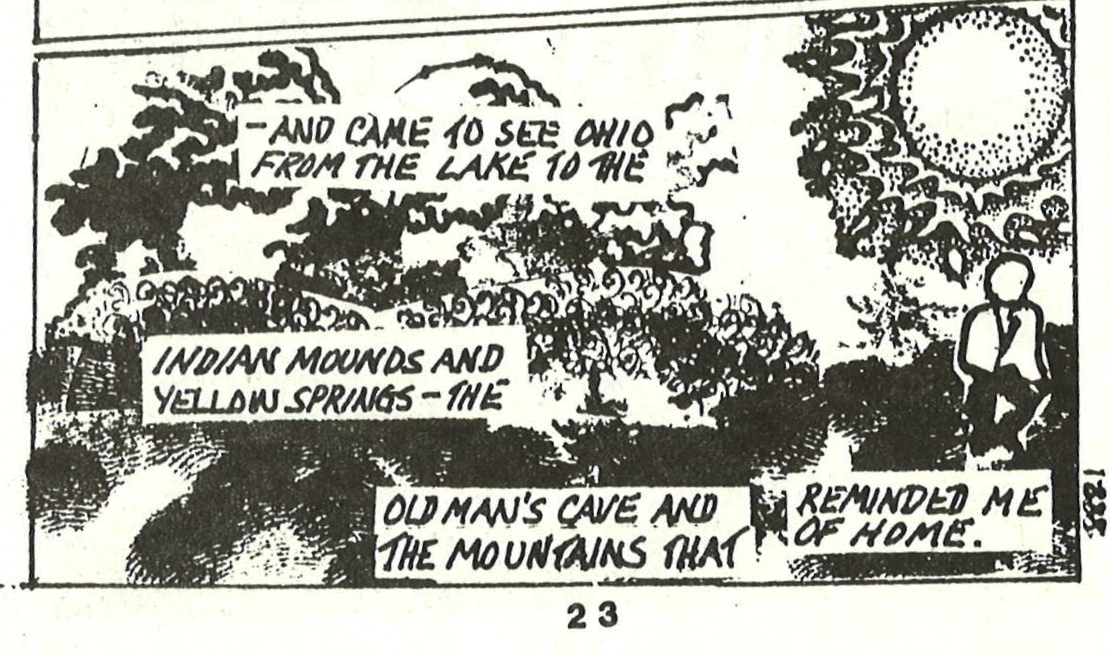

Whereas Copper’s photo-collage is the record of a location, Levin’s story is the diary of a walk from “a place / of very old mountains”—the Berkshires of Western Massachusetts—to what the narrator later describes as “the geographic / and geopolitical / bullseye-center / of the buckeye state,” a place he maps for us on the final page of the story. Our narrator eventually “came to see Ohio / from the lake to the / Indian mounds and / Yellow Springs—the / Old Man’s Cave and / the mountains” as locations which remind him “of home”:

Levin uses his fingerprints in the final panel on the last page of the comic to create a pattern of shadows from which his hero, the Walking Man, emerges. His story is as simple as these images. It is the story of a journey:

Levin’s use of rubber stamps, the repetition of the same fish, the same cattails, the same sun, the same trees, and the same clouds, has told us his story before we have time to read the narrator’s final thoughts: what this wanderer has been searching for he has carried with him. This collection of rubber-stamped figures and panels becomes a map of Amherst, Massachusetts; of Yellow Springs, Ohio; and of his inner world, its silence broken only by his breath.

In his final public speech in 1992, novelist and essayist Ralph Ellison urged other American writers to see their work, whatever form it might take, as a means of manifesting a more just and democratic nation: “I’ll close by reminding my fellow writers, as I frequently remind myself, that you’re doing far more than creating interesting tales based on your individual view of the American experience. Underneath your efforts you’re helping this country discover a fuller sense of itself as it goes about making its founders’ dream a reality” (Ellison 860).

I read Walking Man Comics and Copper’s Untitled as works by American artists who seek to map the United States not at its center but along its perimeter. Copper locates meaning in those precious objects we discard—home movies, family photographs, jumbled cellphone conversations. Levin conjures landscapes of New England and the Midwest from his box of rubber stamps.

Both Levin and Copper remind us that these fleeting, sometimes painful, often playful moments of existence only become real when transformed by art into objects or images which can be shared—the journals of a walking man and the photographs of a young woman.

Are these works of art glimpses of the“founders’ dream”? Yes, each one: the black and white of a rubber-stamped tree, and the curve of a bare shoulder, and a cloudless summer-blue sky, and the red-lipped smile of a woman at play.

_____

Update: A follow up to this post is here.

Fig. 3: A detail from the cover of Levin’s Musicomics #9 (March 2002; first edition March 1996).

References for Print Sources:

Ellison, Ralph. “Address at the Whiting Foundation” in The Collected Essays of Ralph Ellison (Ed. John F. Callahan). New York: The Modern Library, 2003. 853—860.

Moore, Alan. “Alan Moore Original Proposal to Warrior Magazine” in George Khoury (Ed.) Kimota! The Miracleman Companion. Raleigh: TwoMorros Publishing, 2001: 24—29.