When Noah asked me if I would contribute to Hooded Utilitarian’s Anniversary of Hate, I didn’t have too much difficulty coming up with a list of personal candidates. Despite my normal preference for setting aside entertainment I’m not enjoying on the grounds that life’s just too short, over the years, I’ve still managed to amass an artistic shitlist — a list of things I hate so much I’m still angry I read them. So I ran through the list, and thought about writing about how John Ney Rieber’s using The Books of Magic as some kind of writing therapy for his intense self-loathing destroyed one of the most refreshing new characters Neil Gaiman had created for DC. Or about how the increasingly unsubtle and didactic right-wing politics of Bill Willingham in Fables is almost a case study in how not to integrate your personal politics into your work. Man-oh-man, was I ever tempted to pull out my copy of The Best American Comics 2006, and eviscerate a particularly horrible anti-Muslim short story that offended me so much when I read it that I actually gave in to the desire to hurl the book at the wall. (I wanted to pull it out and look up the title of the story, but I recently moved, and it’s in a box. I think. It might be in Massachusetts. I really have no way of knowing.)

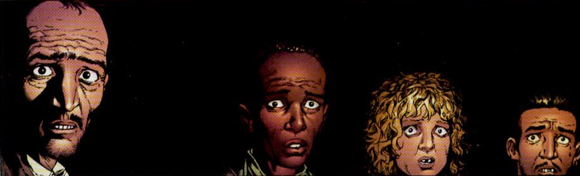

But in the end, I decided to go with an old un-favorite, J. Michael Straczynski’s weirdly personal opus Midnight Nation. Midnight Nation is a twelve-issue limited series that I read a few years ago in hardback, about David, a cynical cop with a heart of blah blah, whose investigation into a gory murder is curtailed when his soul is unexpectedly ripped out by ghoulish monsters. He wakes up and walks right out of his body, essentially a ghost–a soulless ghost; what precisely David is, when he is neither body nor soul, is never discussed–and spends the next year walking cross-country with a mysterious, cranky, half-naked guide named Laurel, trying to reclaim his soul before he himself turns into one of the monsters that removed it in the first place.

Why did I say weirdly personal? The hardback edition I originally read a few years ago was accompanied by an essay penned by Straczynski (which, alas, I have not been able to put my hands on again to refresh my memory), relating a terrifying experience in his youth that he claimed was the direct inspiration for the series. He was walking along a beach one night, and had some kind of near-miss with a gang of violent thugs that apparently opened up to him all the deep secrets of the universe and the perilous balance of humanity.

It does sound a titch traumatic. But the work this encounter supposedly inspired features long speeches about the wretchedness of the human experience manifest in, among many other things:

1) People who talk in theaters

2) Christopher Reeve being confined to a wheelchair

3) Permissible counts of rat droppings in hot dogs

4) War

I’m open to the possibility that the ironic juxtaposition of petty annoyances and profound evils was meant to be witty, but it didn’t read that way. It read stupid; a list of pet peeves someone tried to elevate into profundity. Here are the revelations that come on the heels of a death narrowly dodged: people talking in the theater are just the worst. It’s so sad when bad things happen to people we like. War. What is it good for? Nothing.

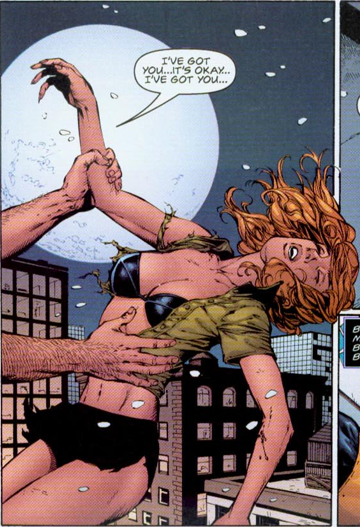

I’m tempted just to list all the absurd little details of the speechifying, but I really should mention the terrible art, since it goes a long way towards making the book as bad as it is. The art is terrible! I don’t know what went wrong–I liked Gary Frank, the penciler, just fine when he worked on the 1990s Supergirl title (that’d be one with a heavy emphasis on Linda Danvers and angels), and he’s a competent artist, but his work on Midnight Nation is characterized by dead-eyed stares, stiff bodies and faces, and character designs that alternate between boring, exploitative, or flat-out stupid-looking. (I’ve never been able to figure out why Laurel spends the first few issues wandering around in an exercise bra, low-rise jeans, and a thong. ((SPOILERS: the best theory I’ve ever come up with is that it’s supposed to be an inversion of angel iconography, an angel being what Laurel is eventually revealed as. But if you can’t manage to undercut religious iconography without making your main character look like a refugee from Victoria’s Secret–well, bite me.)) Or why David’s ghoulish attackers, the Walkers, are green and bald with black tattoos, and wear crazy cultist robes–a colorful aesthetic jarringly out of place with the everyday look of the rest of the book.) Could it have been the inker? The colorist? Maybe Gary Frank had a bad cold that year. Maybe he phoned it in because he hated the script. (Probably not. But I wouldn’t blame him.)

(I tried to describe this comic to my sister, and she said, “I think I’m getting a feel for it– the sort of 90s’ extra-gritty slasher softcore that’s basically an excuse for the author to express his inner teenager.” I told her it’s not all that gritty. “That’s even worse, somehow,” she said.)

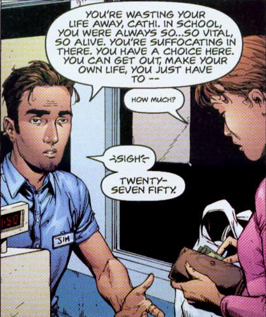

The first time I read Midnight Nation, I just thought it was bad and pretentious and boring. The second time, what mostly occupied my mind was the thought that there is a great dissonance between what I think Straczynski wanted to do, and what he did. I think he wanted to write about the margins of society, the way human beings fall through the cracks of the world and vanish, and where they go, metaphorically, when that happens. It’s the kind of metaphor story Joss Whedon (who I think Straczynski is often compared to, based on some superficial similarities in dialogue) used to pull off so well on Buffy the Vampire Slayer, the kind of interplay of reality and story that made Sandman sublime. But the script is not sublime. It’s awkward and forced. A dead-eyed grocery cashier launches into a moralistic lecture to a dead-eyed customer about how she shouldn’t waste her life, speaking of a lost vitality completely absent from the flashbacks to her childhood. The characters refer to the out-of-phase dimension they inhabit as the metaphor side of things, but the relationship of the metaphor to their reality goes unexplored; it’s simply a setting. Moments that were perhaps meant to convey warmth or wit or fear are left dry and emotionless by the stiff, lifeless art.

I can’t attribute the book’s failures just to the lousy art, though. Straczynski is, after all, responsible for the plot, the pacing, the characterization, the development of relationships, and of course, the dialogue. When Laurel and David first meet, Laurel is intensely hostile to David, refusing to answer his questions, making snide asides, and complaining about being stuck shepherding someone so annoying. When they meet her acquaintances, they also treat David like an idiot, and sympathize with Laurel for being stuck with him. But David’s not that annoying–all of his questions are the obvious ones you’d ask, if you’d been savaged by bald, green cultists with claws and zig-zag tattoos, and started having an out-of-body experience with someone who told you your soul was missing. They’re such obvious questions that they don’t even do anything to establish David’s personality; they’re the rote questions of exposition. What’s Laurel so annoyed about? David’s not irritating, he’s just boring. There’s supposed to be some kind of zesty, push-pull relationship between the weary-and-wise traveler, and the bewildered-yet-spirited greenhorn, but it’s more like watching a confused dog being dragged along by its ill-tempered owner.

The whole book is characterized by this tension between what Straczynski wanted to do, and what actually came out on the page. That shouldn’t be hateworthy–there’s nothing wrong with ambition, and there probably isn’t an artist on earth who hasn’t had a project that failed to live up to their dream.

But I was already dubious about Straczynski when I first picked up Midnight Nation. In fact, the only reason I read Midnight Nation was because of an argument I had with a friend. My friend was a huge fan of Straczynski, but my only encounter with him at that point was in his awful “Sins Past” stint on The Amazing Spider-Man (for those fortunate enough to have forgotten, that’s the one where Gwen Stacy has Norman Osborn’s love babies), which I’d hated. The bad faith of Straczynski’s legendary feud with the writers of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine (in which he encouraged his Babylon 5 fanbase to make accusations of plagiarism on his behalf) had put me off ever getting into the TV show that made his name. But my friend hoped I might change my mind on Straczynski if I got a chance to see what kind of material he could produce when his work wasn’t bound by editorial dictate or hampered by lousy special effects, if I could experience his writing in a context and a medium that didn’t undermine him. This was supposed to be the superlative Straczynski work that turned me around, something where I could see the genius that justified the ego and the dedicated fanbase.

I’m still looking for it.

And that is the thing that has really kept me from simply forgetting all about a comic that is, ultimately, more forgettable than hateable. I’m not a fan of Straczynski. I’m an un-fan. I become less of a fan with every passing year. He’s an arrogant person, someone who starts petty feuds with his peers, writes the shittiest storylines editorial can dream up, and is cheerfully complicit in fucking over a fellow artist because eh, bad contracts happen.

If you’re going to be that big of an asshole, you need to be a goddamn genius. A goddamn genius ought — when paired with a halfway competent artist and given the chance to write a twelve-issue miniseries whose concept was inspired by what he claims was a profoundly life-changing personal experience — to be able to produce something beautiful, something memorable, something that tells a truth so undeniable that I retire from it shaken, drained, wondering and muttering its wisdom; the trick, William Potter, is not minding that it hurts. Something that doesn’t feature cheap titty shots and does not weigh tainted hot dogs equally as heavy as the hell of war. It’s become impossible to untangle my disdain for the work and my loathing of the creator. I can’t read the arrogant “let me whisper the dark secrets of the universe, so that you may comprehend and choose” speeches of Midnight Nation‘s villain without thinking that’s Straczynski’s voice, so smug and sure that he’s got it all figured out. Every time I hear about some dickish thing Straczynski has said or done with regards to one of his fellow writers, I think to myself, “Where does he get off? His book was terrible.” I can’t even figure out why this guy gets work, much less how he’s managed to attract a rabid fanbase.

__________

Click here for the Anniversary Index of Hate.