This first appeared on Kiva’s blog.

___________

Fan fiction gets a really bad rap. It’s barely even acknowledged (even when everyone knows about it) and when it finally is, it’s dismissed as juvenile. Something teenage girls with terrible writing skills write, but no self-respecting author actually engages with. We are quick to judge fan fiction authors and readers, and we certainly don’t admit that we are these people.

I’m gonna right come out and say it because I would be that hypocrite if I didn’t: I read—and write—fan fiction.

It gives me a chance to flex my creative muscles without having to develop entire worlds, because someone’s already done the hard part. And as for reading it, well, sometimes, okay, most times, writers don’t see their characters entirely the way I do. The internet does. They fill in the blanks the way I want them to be filled. (I’d say “no pun intended” but with me, the pun is always intended.)

As a bisexual, I’m pretty much always tired of the complete lack of representation when it comes to LGBTQ+ characters. We don’t get many, and when we do, their storylines tend to revolve completely around being gay, as if we have no other interests. And good luck ever getting someone who’s into multiple genders to actually identify as bisexual. They’re always someone who “doesn’t like labels” which is so different to my experience. I love labels! Get me a label maker that exclusively churns out the word bisexual! Cause I wanna put that shit everywhere!

So yeah, we don’t get tons of characters to work with. However, we do get tons of characters who seem like they are expressing attraction to multiple genders or their same gender but it’s just…never addressed. In the end, they end up much more developed than their gay counterparts, but inevitably straight and we are disappointed. (By the way writers, that’s called queer baiting. You know you’re doing it and you’re all assholes.)

Sometimes I want to know more about That Thing The Writers Never Talk About. Obviously, the show’s never going to give me all of what I want. (Just enough of what I want to keep me watching forever in hope and denial.) But fan fiction does. That lingering moment that looks like it’s straight out of a regency costume drama in the new Star Wars? Fan fiction goes hard on that, and that’s the kind of content I wish I could get from the movies but know I never will. When Disney lets me down, the internet’s always there for me.

And okay, this kind of stuff may not be your cup of tea. I get it. Not everyone wants to read about two Presumed Straight dudes boning. That’s your prerogative. But you don’t get to shame people who do. Because everything you love is fan fiction too.

Renaissance paintings, often regarded as some of the finest art in the world, use the stories of The Bible and Classical mythology. That’s fan fiction.

The Aeneid, a piece of epic poetry read by every student of the Classics and then some, uses the stories of Homer. That’s fan fiction. (Of fan fiction, because Homer himself was working from oral traditions.)

House, M.D., an award-winning show about a crotchety doctor and his heterosexual life-partner, is a clear allusion to Sherlock Holmes. That’s fan fiction. (And, quite frankly, an “if Sherlock was a medical doctor” AU.)

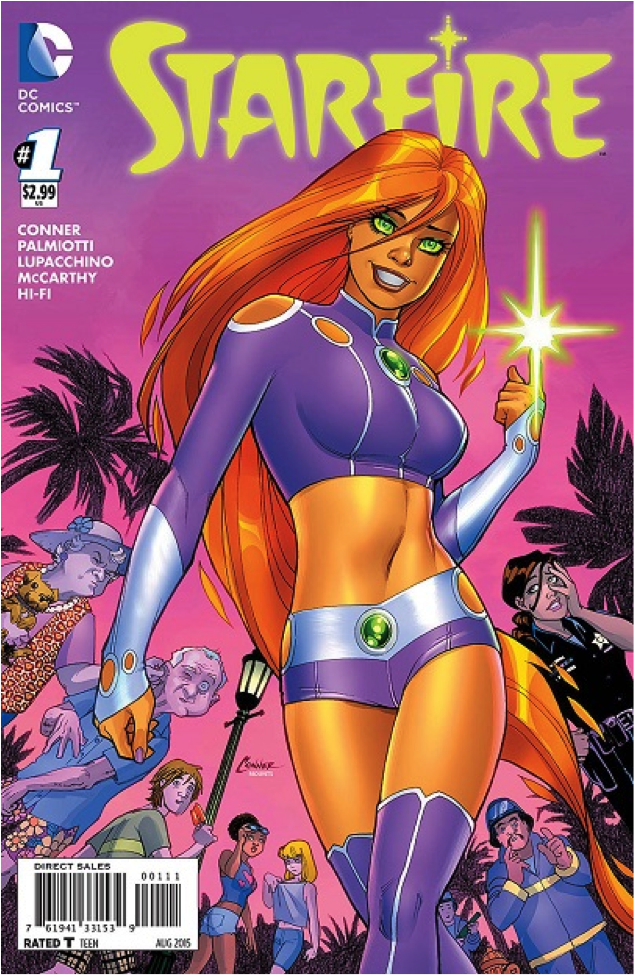

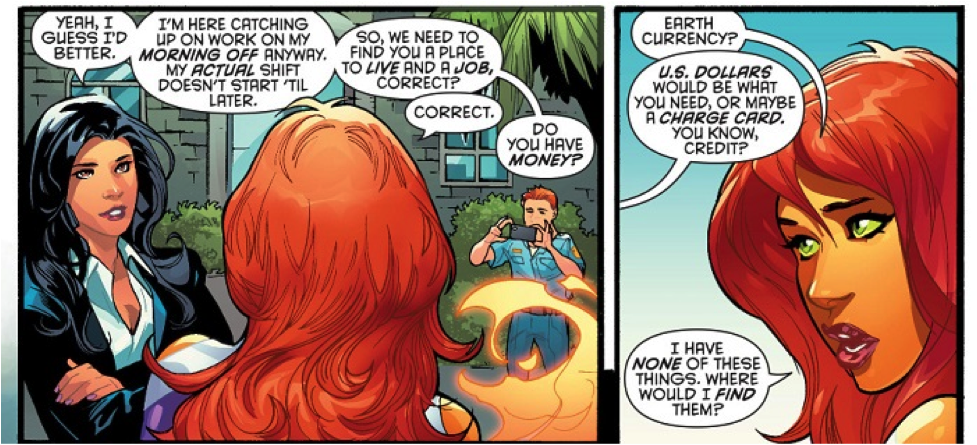

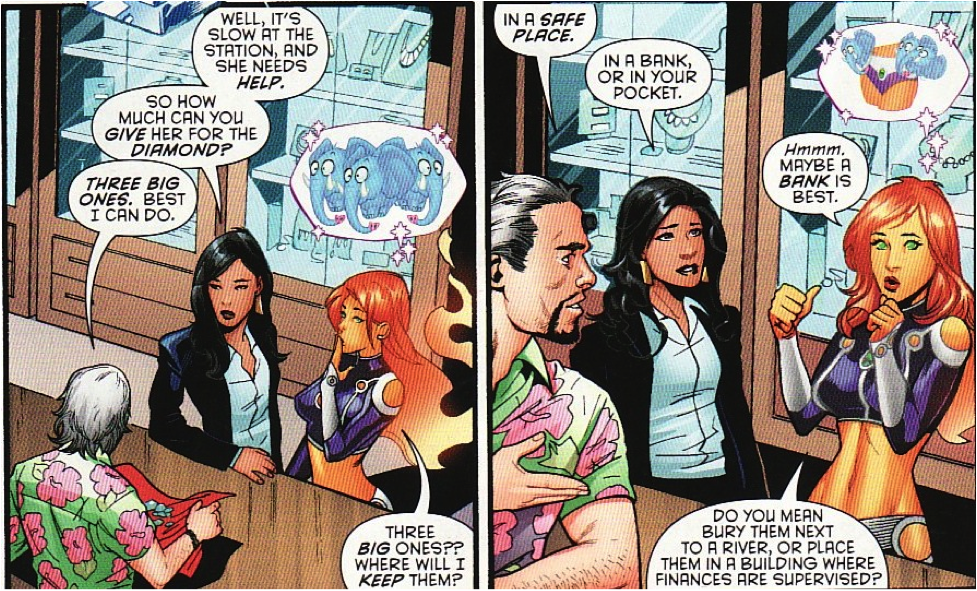

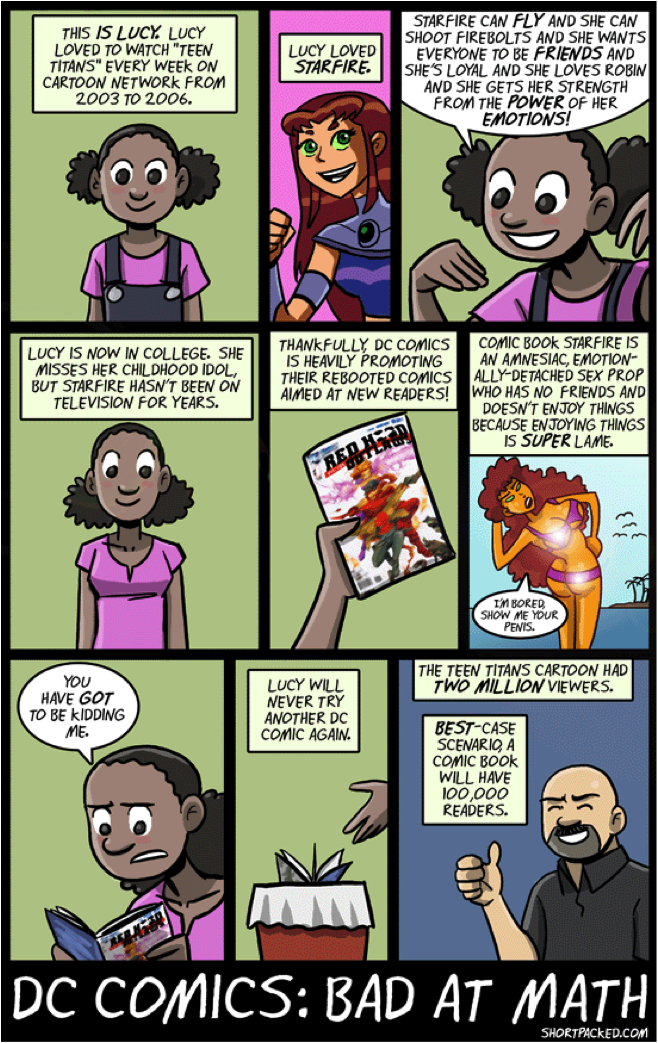

Every single superhero movie, the trendiest thing in film right now, takes established comic book characters and tells new stories with them. That is, almost literally, the definition of fan fiction.

A ridiculously popular Twitter account builds on the characterization of Kylo Ren in The Force Awakens. THAT’S FUCKING FAN FICTION.

Denouncing fan fiction and avoiding it at all costs is stupid because, as my wise friend Renee once put it, “all fiction is fan fiction.”

“But those examples are different!” I hear you saying already.

Why? Why does something need to be either old or big budget or meme-worthy to not be considered insidiously fan fiction-y?

I’ll tell you why you immediately think your precious Marvel Cinematic Universe movies are somehow exceptions to Renee’s Law: Because when something’s old or big budget, there’s a 99% chance it was created by a man. And if it’s created by a man, it can’t in any way be akin to that stuff on the internet nobody talks about save for criticizing. But that’s classic sexism.

Stop vilifying teenage girls for what you praise men for doing. Internet fan fiction is a community largely comprised of women. That is the reason it is looked down on. That is the reason men will go through some serious cognitive dissonance to say that girls write fan fiction, but they don’t. And I simply do not have the patience for it anymore.

Male creators of the world: you write fan fiction. Admit it.

And furthermore, stop condemning those who read online fan fiction. Studies have shown that some women respond to erotica more than porn. And if you don’t believe the studies, believe the success of Nora Roberts. However, some of us, while responding to erotica, don’t respond to romance novels about boring, snooze-fest heterosexuals we have had no other interactions with. We respond to (yes, that) fan fiction.

Teenage girls have become more comfortable with their sexual identity and are empowered by their sexuality because of writing and reading fan fiction. They shouldn’t be shamed for their desire and they shouldn’t be shamed for how they discovered it. The disparagement of fan fiction, and the girls who engage with it, is ultimately a microcosm of patriarchal society at large.

Noah Berlatsky wrote a piece for the LA Times titled “‘Batman v Superman’ is fan fiction, and that’s OK”. I only amend it to be more inclusive:

Everything is fan fiction, and that’s OK.