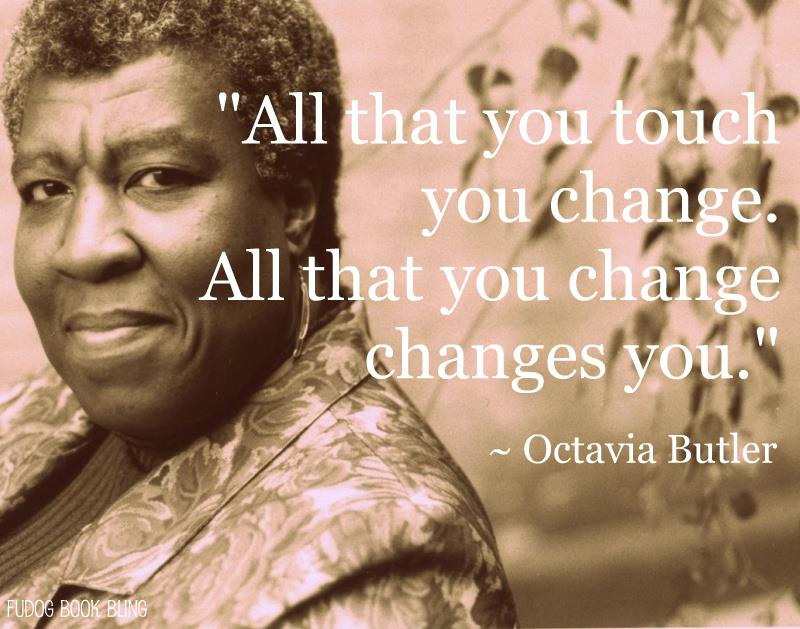

This is part of a roundtable on the work of Octavia Butler. The index to the roundtable is here.

__________

If we count not only the unusually severe harms that anybody could endure, but also the quite routine ones of ordinary human life, then we find that matters are still worse for cheery procreators. It shows that they play Russian roulette with a fully loaded gun — aimed, of course, not at their own heads, but at those of their future offspring. – David Benatar, Better Never to Have Been, p. 92

Benatar’s anti-natalism is not likely to capture the popular imagination any time, soon; probably never, I’d wager. What kind of person accepts that it would be for the best should humanity stop reproducing? But a few metaphysical defeatists do indeed take some solace in it, at least by discovering a comrade in bleakness who attempts rational arguments for our shared existential plight – justifications that aren’t reducible to some mere psychological fracture. The psychologistic dismissals of pessimism are widespread, most recently and disappointingly exemplified by writer Nic Pizzolatto in his TV series, True Detective. Disappointing, because Pizzolatto clearly shares my love for the most ontologically downtrodden horror author working today, Thomas Ligotti. Nevertheless, after 7 hours of episodes that dismantle straight guy Marty Hart’s ideas of family, hard work and law as delusional distractions which keep him from confronting the abysmal punchlines consistently delivered by pessimistic funny man Rust Cohle, and despite having the latter nearly quote Ligotti verbatim at times, Pizzolatto betrays all of this with a denouement that makes the show into little more than religious propaganda hidden in a blighted form. Rust has a metaphysical conversion in the finale after a near death visitation by his dead daughter and father: he begins to see little rays of hope peeking out of the darkness of the nighttime sky. Turns out it was the trauma of losing a child and of not having reconciled with his father – genetically, a future deadend and an unresolved past – that lead to those previously expressed dark thoughts, and not, say, facing the objective ramifications of the eternal perspective, or sub specie aeternitatis, which can only reveal an end to humanity, its concerns and all its artifacts. Rust and the audience need no longer worry about such ramifications with the hope of continuing as an immortal soul. Ligotti refers to such pessimistic flimflam as a “façade of ruins, a trompe l’oeil of bleakness.” (Ligotti, p. 147)

Another shell game with hope is played out in Alfonso Cuarón’s Children of Men where an inexplicable apocalyptic plague has resulted in universal infertility. Regarding anti-natalism, Peter Singer naïvely wonders, “If we would all agree to have ourselves sterilized then no sacrifices would be required — we could party our way into extinction!” Instead, the film offers a more psychologically plausible scenario: With humanity facing its true endgame, the last generation behaves like a coyote chewing through its ensnared limb, only to realize that each of its limbs is equally trapped. There’s no shared hedonistic spirit, where the world turns into one big Burning Man festival, rather the state (England) erects more barriers, whereby the more privileged, based on the same old fears of class and race, try desperately to reduce the possibilities of the less fortunate ruining whatever pleasures are left in the one thing everyone is forced to share, a moribund genetic fate. Shit never stops running down hill. What the film suggests is that thanatopobia is part of our psychological foundation. “To subdue our death anxiety, we have trumped up a world to deceive ourselves into believing that we will persist – if only symbolically – beyond the breakdown of our bodies.” (Ligotti, p. 159) When we can no longer postpone reflecting on the nothingness of the final true death to some future progeny, we can no longer rely on the comforts of a symbolic immortality. The film suggests we would behave like caged animals. But, then, one of those rays of hope shows up in the form of a pregnant woman, suggesting the human race isn’t finished yet. After which, the story becomes one of a formerly defeatist protagonist making sacrifices for the benefit of some future society that he hopes (with his re-discovered faith) will be better than the current one. The ending is ambivalent enough that the materially inclined need not feel betrayed like we were with True Detective, but it still gives the viewer an emotional escape hatch (unsurprising, I suppose, if you already knew that the book on which the movie was based is by a devout Anglican).

Likewise, thanatophobia – the maternal instinct being the relevant strain here – is the structuring motivation running through Octavia Butler’s tale of survival at any cost, Xenogenesis (aka Lilith’s Brood). After a nutwing contingent of ideologues wipes out most of the life on Earth with nuclear bombs, the few remaining humans are “rescued” by the Oankali, a parasitical species of date-raping colonialists with grotesque worm-like sensors all over their bodies who solve most of their problems with the evolved ability of genetic manipulation, a biologically inherited eugenics. Their means of survival is, like capitalism or the culture industry, to consume qua incorporation all the different beings and materials they find across the universe into their own genetic history, making the new more of the same.

What’s particularly interesting about Butler’s take on the alien invasion trope is that she focuses on a human collaborator, Lilith, and not the heroic figure of the resistance fighter. Not that there’s much possibility for resistance once Lilith is awakened from her stasis, hundreds of years after the nuclear winter. The aliens have rebuilt much of the Earth’s topography and restructured the humans to suit their expansionist goals, which amount to serving the Earth as food to their massive living spaceships and propagating a new strain of the Oankali species using the human gene pool as a reproduction machine. Use it all up and move on. The only two forms of rebellion left to the humans are bitching a lot among themselves and a noncompliance that will result in an eventual death that’s not much more than long-form suicide. Lilith chooses the symbolic immortality of humanity by helping her fellow Terrans accept the idea of humanity becoming one more admixture to the collective genetic memory of the Oankali.

But I doubt Butler would agree with my negative description of the Oankali, since she rationalizes most of their oppressive behavior as the story progresses. However objectionable they may at first seem, they look much more like a perfectly harmonic anarchy of superheroes by the end of the series. Thus, what begins as the subjugation of humanity turns out to be its salvation. The Oankali understand each other, other living beings and the world around them on precognitive levels, genetically and materially. They don’t need the muddying mediation of language, since they can objectively tell if no means yes. Humans might be cognitively confused, but the Oankali can see the essential truth underneath. Butler is clearly sympathetic to their collectivism, setting it up as a utopian vantage point, her sub specie aeternitatis, from which to critique what she considers humanity’s defining problem, the human contradiction. That is, humans have a biological characteristic for being hierarchical, which is seen in many other animals, too, but it results in stuff like nuclear warfare when reinforced – rather than, as Jdahya explains, “guided” – by the other major human feature, intelligence. (p. 41, Xenogenesis)

There’s a good bit of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s early pessimism in how the Oankali (and Butler, evidently) perceive humans. His version of our fall from grace: When humans were closest to our animalistic predecessors, as natural man, lacking reflection, we simply existed in the present, moment to moment, like all animals. Even though there was a natural hierarchy, some serving as food for others, all animals, including early man, remained in a satisfied state of blissful ignorance. Worms don’t think about how awful their lives under the domination of birds; both simply do what they do. But once self-consciousness set in with the development of language, humans were capable of considering whether we’re better off now than previously and of making plans. This is time consciousness, which meant that we began to think about what things were like and what they may be like in the future, providing us with the faculty of perfectibility. Perfectibility relies on a perpetual dissatisfaction with our present situation based on comparisons to our past and imagined future selves and to other humans. This alienation from the present is what led, on the one hand, to the development of, say, moral thought or imagining a better polity, and, on the other, to the fear of death, or “our subjugation to the opinion of others [that] paves the way for direct political subjugation.” (p. 69, Dienstag, whose interpretation of Rousseau I follow here)

Rousseau mused about utopian arrangements that would help shelter modern man from time consciousness, where we might rediscover the authenticity of natural man, no longer feeling enslaved to the opinions of others. But, because we can’t forget all the knowledge that’s been acquired over our history, nor can we rid ourselves of temporality, he was highly doubtful that that we could ever return to primeval happiness. But aren’t the Oankali just such a fantasy of an advanced civilization that lives in an animalistic present? Their genetic telepathy makes language otiose while giving them a complete awareness of everything around them. Because of that link, they exist in a natural collective state that is inherently cooperative and anti-competitive. They don’t use tools, but they’ve plenty of organic technology, which is capable of the most advanced scientific feats, such as space travel. And because of their genetic memory across generations as well as a control of aging, they have no anxiety about death. Perfectibility is a matter of adapting to and merging with the surrounding organic forms – of tuning into their present environment, not being alienated from it.

Using the Oankali as an impossible fantasy for perfecting humanity seems to me at odds with the story’s other major theme, moral responsibility for the subjugated. This is why the trilogy begins to lose ideological steam as Butler becomes increasingly interested in the alien culture itself (focusing on Lilith’s brood and Oankali politics) in lieu of how the humans behave under its dominion. Making substantive points about collaboration becomes difficult when human survivors ultimately should be thanking Lilith for being their Moses to an eternal Oankali paradise. Consequently, I prefer the short story, “Bloodchild,” which Butler wrote while doing research for the trilogy. It explores many of the same themes without the wish fulfilling distractions: The Tlic, an intelligent insect-reptile hybrid with scorpion tails bond with human boys early in their life as a way of preparing them to be symbiotic incubators for the alien species’ vein-munching larvae. (Males are used as hosts, because females are needed to birth enough males to meet Tlic demand.) Humans have once again fucked up everything sometime in the past – this time, by making Earth into some slave-based dystopia. So some refugees found their way to the Tlic’s planet, where the master-slave relation proved more agreeable than back home. As in Xenogenesis, the humans survived only through a diminishment of their humanity. However, there is no potential for perfectibility by becoming part of the Tlic’s reproductive process. They have pretty much the same contradiction that we do.

It’s a coming of age story in which the adolescent Gan is getting ready to have T’Gatoi, an important Tlic bureaucrat and longterm family friend, implant her larval eggs into his bloodstream. His mother, Lien, agreed to this long ago, his father was a host before him (he carried T’Gatoi), and Gan has been raised to accept it as his purpose. The family gets plenty of food and privileges through their relation with T’Gatoi. Gan only begins to question his fate after witnessing the way the little Tlic grubs, ready to be delivered, begin to feed on their host until they can be moved to the corpse of an indigenous beast. This bloody act of physically substituting one body for another helps him realize that his existence is reduced to being a host animal. He seriously considers suicide to prevent himself from being either a mere means for T’Gatoi or the living dead existence of his brother, Qui, who’s resigned to wandering about the preserve on which they live, high on the narcotic egg juice that the Tlic supply to keep the humans living long and pacified lives. But if he doesn’t serve as host, his sister Hoa will; in fact, she even wants to. To save his sister from such a fate, he recommits himself to the task. However, he doesn’t explain it (in first person) as a mere sacrifice on his part, but as a personal desire: “[T’Gatoi:] ‘But you came to me … to save Hoa.’ [Gan:] ‘Yes.’ I leaned my forehead against her. She was cool velvet, deceptively soft. ‘And to keep you for myself.’” (Loc 340) Despite Butler’s insistence in the afterword (Loc 364) that this is a story about love, not slavery, the differential power involved makes her interpretation about as reasonable as a non-ideological romance between Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson.

Similarly, when Lien shows signs of depression at having provided her children for Tlic reproduction, T’Gatoi responds by drugging her, using a sting of the Tlic’s tail and insisting that she drink more egg juice. No matter that T’Gatoi and Lien grew up together, the friendship, just like all forms of love between the two species, is corrupt and not to be completely trusted, regardless of how either side might interpret the relation. The dominating to dominated class hierarchy won’t allow anything more. Hardly limited to a slave economy, Butler makes a much better case against hierarchical discrepancies in this short story than she manages in the entire trilogy that followed. That’s because without a utopian interpretation of the alien superiors here, subjugated choice (qua love) is potently problematized, and the effects of domination are critiqued.

Although “Bloodchild” is a perfectly miserable gem that encourages a properly depressive reaction, it still focuses, just like every other example discussed so far, on the will to survive through a high sacrificial cost of some sort (in the case of Gan’s family, basic human dignity). When it comes to sowing the seeds for the future of humanity, our moral options, in fiction and for most people, are limited by a perverse optimism, which Ligotti (p. 154) summarizes as Frankenstein’s Oath: “We, as licensed protectors of the species and members in good standing of the master-class of the race, by the power invested in us by those who wish to survive and reproduce, vow to enforce the fiction that life is worth having and worth living come hell or irreparable brain damage.” As the aforementioned Benatar suggests, this Pollyannaism is justified by the low expectations of humans, sub specie humanitatis. We’re quite good at adapting to suffering and, like Gan, accommodating oppressive beliefs as our own when we have so little real choice. As he puts it, “we would not take slaves’ endorsement of their enslavement as a justification for their enslavement, particularly if we could point to some rationally questionable psychological phenomenon that explained the slaves’ contentment.” (p. 100, Benatar) He argues for another moral possibility, which should come as no surprise if you read the epigraph.

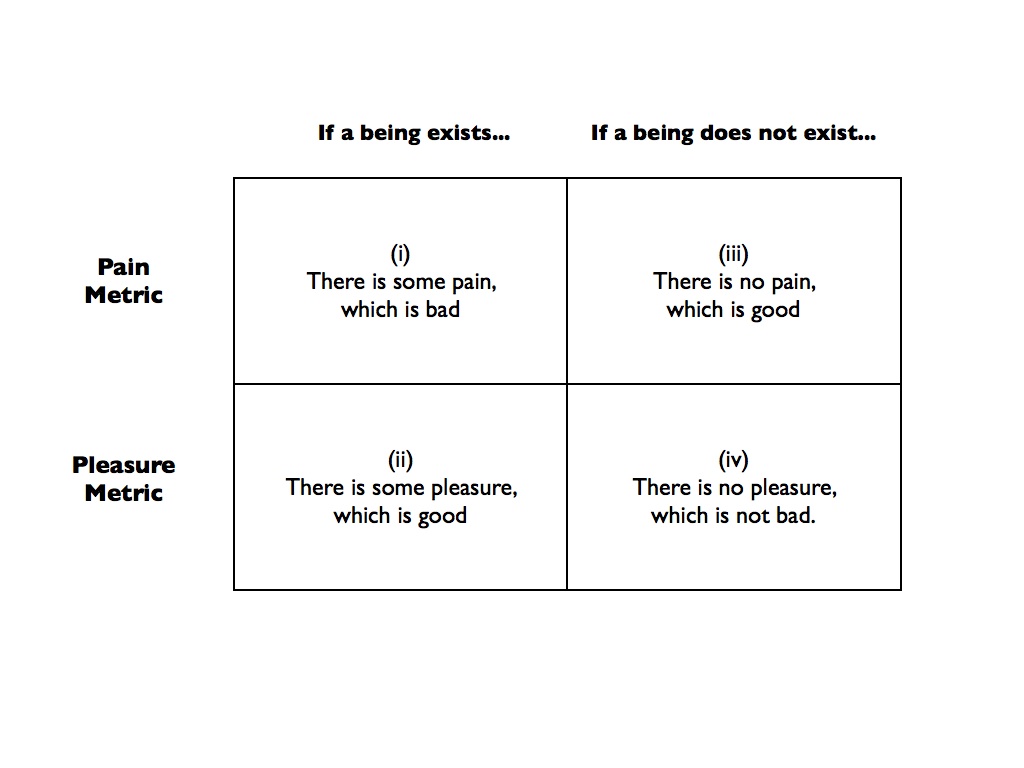

Regarding future-life cases 1 – i.e., the potential lives of people yet to be born and who are presently non-existent – Benatar makes the case for a fundamental asymmetry in how we evaluate whether it’s good or bad to bring them into existence such that the moral view is that we never should. In one scenario, Lilith brings X into existence, in which case we would say that X experiencing pain is bad and X’s experiencing pleasure is good. That’s agreeable enough, I think, but the problem comes in when we consider what happens should Lilith choose to not bring X into existence. The absence of pain is good even without X to enjoy it. That is, independently of any pleasure, it’s better to not have X than to have X in pain. However, pleasure doesn’t work out in an equally symmetrical fashion. The absence of pleasure isn’t bad unless X exists to be deprived of it. And since X doesn’t exist in this scenario, there’s nothing bad (but nothing good, either) about non-X not experiencing pleasure (since no one’s missing anything). It would be neither better nor worse to not have X who will experience no pleasure than to have X will experience some pleasure. Because it’s good to avoid bringing into the world whatever inevitable amount of suffering that will befall X by not having X, and nothing bad (nor good) would occur should Lilith not have X, she shouldn’t have X, nor should she ever have an X or Y or Z. The same goes for all of us humans, as well as the Tlic, but probably not for the Oankali, since pain isn’t really such a bad thing for them. Therefore, the collaborators in Xenogenesis and “Bloodchild” are not doing humanity any favors by doing whatever’s necessary to survive. They’re actually bringing unnecessary harm into the world, particularly since humanity continues only under the “thumb”/tentacle/tarsus of alien oppressors.

Benatar’s argument isn’t likely to convince the optimistic majority as it leads to some really uncomfortable positions, such as a pro-death view of abortion (women shouldn’t just have a legal right to choose, but should always use that right to abort) and that we should let the species die out even in the absence of extraterrestrial domination. And it has received some stiff philosophical challenges. However, he does offer intuitive support for his asymmetry by showing how it provides a basis for other more commonly accepted asymmetries. For example, most people probably share the view that we have a duty to not bring babies into the world that we know will greatly suffer (such as a fetus that tests positive with an incurable degenerative disease), but not the inverse duty to bring happy people into the world (there’s certainly nothing immoral about a kind and caring couple deciding to not have children). Benatar’s asymmetry provides a possible reason: It’s good not to have children with incurably painful diseases, but neither bad, nor good for children who don’t exist to not experience happiness – i.e., the couple who decides to not have a child isn’t depriving a non-entity of happiness. But, even if that doesn’t sound plausible, the argument is refreshing just because it runs counter to the popular temptation to justify whatever moral position one has with a just-so story from evolutionary psychology. Could there be an ethical view less biologically adaptive than anti-natalism? If for no other reason, I appreciate the effort.

Showing sympathy for Benatar’s conclusion is Joanna Russ’ heroine, Elaine, in the relentlessly anti-utopian We Who Are About To …. With no hope of being rescued, she lets her fellow castaways know what she thinks about their plan to rebuild civilization on the planet where they’ve crashed:

All right, so you think you have the chance of a snowball in hell. Maybe you do. But I think that some kinds of survival are damned idiotic. Do you want your children to live in the Old Stone Age? Do you want them to forget how to read? Do you want to lose your teeth? Do you want your great-grandchildren to die at thirty? That’s obscene. (p. 14)

Taking a poke at stories like “Bloodchild” where humans fleeing from Earth always manage to discover advanced alien civilizations on other planets, this new planet is a barely hospitable environment with no signs of mental life, civilized or otherwise. There are so few women and men that all the others are not going to allow Elaine (or anyone else) to opt out of reproduction. The central struggle in the book is, as Samuel Delany discusses in his introduction, whether quality of life or reproduction provides purpose to our existence. Insisting on a right to die, she’s forced to kill all but two of the group, because they chose suicide. Elaine isn’t just skeptical like Rousseau that we could revert back to the state of natural man, she has no desire to do such a thing, fearing what a return to a natural hierarchy would likely mean:

You must understand that the patriarchy is coming back, has returned (in fact) in two days. By no design. You must understand that I have no music, no books, no friends, no love. No civilization without industrialization! I’m very much afraid of death. But I must. I must. I must. Deliver me from the body of this. This body. This damned life. (p. 21)

Once alone, Elaine records her final thoughts into a recorder (the narrative conceit of the book) as she starves in a cave, waiting for the proper moment to use a poison capsule. In place of the thanatophobic maternal instinct or Stockholm syndrome as love or a utopian dream that justifies a suffering existence, this is a violent stand for human and, more specifically, female dignity.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Footnotes:

1. Present-life cases involve the continuance of a life, the cessation of which involves a different threshold for suffering from the one regarding whether a life should never be started.

References:

Benatar, David (2008), Better Never to Have Been: The Harm of Coming into Existence. Oxford University Press.

Butler, Octavia (1996), Bloodchild and Other Stories. Open Road Integrated Media.

Butler, Octavia (1987, 1988, 1989), Xenogenesis. Guild America Books.

Dienstag, Joshua Foa (2006), Pessimism: Philosophy, Ethic, Spirit , Chapter 2. Princeton University Press.

Ligotti, Thomas (2010), “Sick to Death” in The Conspiracy against the Human Race, p. 147-167. Hippocampus Press.

Russ, Joanna (1976), We Who Are About To …. Wesleyan University Press.

Other Notes:

Children of Men poster is by Noah Hornstein.

Benatar diagram was borrowed from here, which also has a summary of the argument should mine not be sufficiently clear.

Finally, ‘Loc’ refers to the location in a an ebook edition I have of Bloodchild. This is different from the page numbers.