By Joy DeLyria and Sean Michael Robinson

There are few works of greater scope or structural genius than the series of fiction pieces by Horatio Bucklesby Ogden, collectively known as The Wire; yet for the most part, this Victorian masterpiece has been forgotten and ignored by scholars and popular culture alike. Like his contemporary Charles Dickens, Ogden has, due to the rough and at times lurid nature of his material, been dismissed as a hack, despite significant endorsements of literary critics of the nineteenth century. Unlike the corpus of Dickens, The Wire failed to reach the critical mass of readers necessary to sustain interest over time, and thus runs the risk of falling into the obscurity of academia. We come to you today to right that gross literary injustice.

The Wire began syndication in 1846, and was published in 60 installments over the course of six years. Each installment was 30 pages, featuring covers and illustrations by Baxter “Bubz” Black, and selling for one shilling each. After the final installment, The Wire became available in a five volume set, departing from the traditional three.

Bucklesby Ogden himself has most often been compared to Charles Dickens. Both began as journalists, and then branched out with works such as Pickwick Papers and The Corner. While Dickens found popularity and eventual fame in his successive work, Ogden took a darker path.

Dickens’ success for the most part lies in his mastery of the serial format. Other serialized authors were mainly writing episodic sketches linked together only loosely by plot, characters, and a uniformity of style. With Oliver Twist, only his second volume of work, Dickens began to define an altogether new type of novel, one that was more complex, more psychologically and metaphorically contiguous. Despite this, Dickens retained a heightened awareness of his method of publication. Each installment contained a series of elements engineered to give the reader the satisfaction of a complete arc, giving the reader the sense of an episode, complete with a beginning, middle, and end.

One might liken The Wire, however, to the novels of the former century that were single, complete works, and only later were adapted to serial format in order to make them affordable to the public. Yet, while cognizant of his predecessors, Ogden was not working in the paradigm of the eighteenth century. As a Victorian novelist, serialization was the format of choice for his publishers, but rather than providing the short burst of decisively circumscribed fiction so desired by his readership, his tangled narrative unspooled at a stately, at times seemingly glacial, pace. This method of story-telling redefined the novel in an altogether different way than both Victorian novelists and those who had come before.

The serial format did The Wire no favors at the time of its publication. Though critics lauded it, the general public found the initial installments slow and difficult to get into, while later installments required intimate knowledge of all the pieces which had come before. To consume this story in small bits doled out over an extended time is to view a pointillist painting by looking at the dots.

And yet, there is no other form in which The Wire could have been published other than the serial, for both economic and practical reasons. The volume set, at 3£, was an extraordinary expense, as opposed to a shilling per month over six years. Furthermore, while The Wire only truly received praise from scholars, it was produced for the masses, who would be more likely to browse a pamphlet than they would be to purchase a volume set.

Lastly, one might stand back from a pointillist work; whereas physically there is no other way to consume The Wire than piece by piece. To experience the story in its entirety, without breaks between sections, would be exhausting; one would perhaps miss the essence of what makes it great: the slow build of detail, the gradual and yet inevitable churning of this massive beast of a world.

The genius of The Wire lies in its sheer size and scope, its slow layering of complexity which could not have been achieved in any other way but the serial format. Dickens is often praised for his portrayal not merely of a set of characters and their lives, but of the setting as a character: the city itself an antagonist. Yet in The Wire, Bodymore is a far more intricate and compelling character than London in Dickens’ hands; The Wire portrays society to such a degree of realism and intricacy that A Tale of Two Cities—or any other story—can hardly compare.

That is not to say that one did not have an influence on the other. Oliver Twist is a searing treatment of the education system and treatment of children in Victorian society; meanwhile, The Wire’s portrayal of the Bodymore schools is a similar indictment, featuring Oliver-like orphans such as “Dookey” and the fatherless Michael, and criminal activity forced upon children with Fagin-like scheming. Yet while Ogden no doubt took a cue from Dickens in his choice to condemn the educational institution, The Wire builds from the simplicity of Oliver Twist, complicating the subject with a nuance and attention to detail that Dickens never achieved.

In fact, Dickens, in later novels—which incriminate fundamental social institutions such as government (Little Dorrit), the justice system (Bleak House), and social class (A Tale of Two Cities, among others)—seems to have been influenced by The Wire. This is evidenced by the increased complexity of Dickens’ novels, which, instead of following the rollicking adventures of one roguish but endearing protagonist, rather seek to build a complete picture of society. Instead of driving a linear plot forward, Dickens, in A Tale of Two Cities and Bleak House, seeks to unfold the narrative outward, gradually uncovering different aspects of a socially complex world.

While Dickens is lauded for these attempts, The Wire does the same thing, with less appeal to the masses and more skill. For one thing, The Wire’s treatment of the class system is far more nuanced than that of Dickens. Who could forget “Bubbles”—the lovable drifter, Stringer Bell—the bourgeois merchant with pretentions to aristocracy, or Bodie—who, despite lack of education or Victorian “good breeding”, is seen reading and enjoying the likes of Jane Austen? Yet these portrayals of the “criminal element” always maintain a certain realism. We never descend into the divisions of “loveable rogues” and truly evil villains of which Dickens makes such effective use. Odgen’s Bodie, an adult who uses children to perpetrate criminal activity, is not a caricature of an ethnic minority in the mode of Dickens’ Fagin the Jew.

In fact, none of The Wire’s villains have the unadulterated slimy repulsion of David Copperfield’s Uriah Heep, except for perhaps the journalist, Scott Templeton. The final installments of The Wire were sometimes criticized for devolving into Dickensian caricature in regards to the plots surrounding Templeton and The Bodymore Sun. (It is interesting to note first that Dickensian characterizations were Templeton’s number one crime, and second, that these critics of The Wire were for the most part journalists themselves.)

If at any time besides its treatment of Templeton The Wire flirts with caricature, it does so in the character of Omar Little. Yet no one would ever reduce such a monumental culmination of literary tradition, satire, and basic human desire for mythos as Omar Little by defining him as mere caricature. Little is not Dickensian. Nor is he a character in the style of Thackeray, Eliot, Trollope, or any of the most famous serialists. If he must be compared to characters in the Victorian times, he most closely resembles a creation of a Brontë; he could have come from Wuthering Heights.

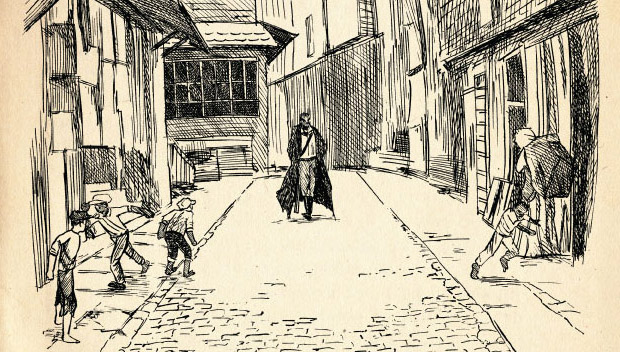

The reason that Little so closely resembles a Brontë hero is of course that the estimable sisters were often not writing in the Victorian paradigm at all, but rather in the Gothic. Their heroes were Byronic, and Lord Byron himself took his cue from the ancient tradition of Romance, culminating in Spenser’s Faerie Queene, but originating even further back. Little would not be out of place in Faerie Queene, and even less so in Don Quixote: an errant knight wielding a sword, facing dragons, no man his master. The character builds on the tradition of the quintessential Robin Hood and borrows qualities from many of the great chivalric romances of previous centuries. Meanwhile there is an element of the fey, mirroring Robin Hood’s own predecessor—Goodfellow or Puck—and prefiguring later dashing, mysterious heroes who also play the part of the fop, as in The Scarlet Pimpernel.

As previously mentioned, Little also has the flavor of the Gothic: brooding, hell-bent on revenge. Indeed, there is a darkness to the character that would not suit Sir Gawain, but does not seem out of place in a Don Juan or Brontë’s Heathcliffe. Little is in fact an amalgamation of these traditions, an essential archetype.

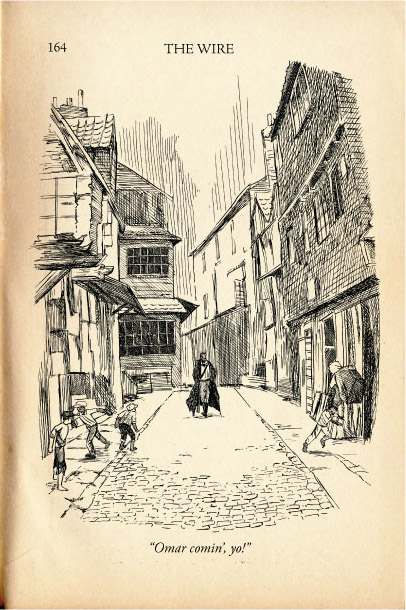

Yet, despite all this, Little can still not be called caricature. There is an awareness of literary canon in Omar Little, a certain level of dramatic irony. The street children and rabble, so Dickensian in their miscellany, always announce his presence, and even as The Wire grows and expands, so does the legend of Little. The Wire is aware of the mythic quality of its character, and allows the rest of the cast to observe it, indirectly commenting on the literary traditions from which Omar Little sprang. Only in the Victorian Age could Romanticism, Gothicism, and poignant satire come to a head in such a trenchant examination of the way such archetype endures. It is lamentable that our culture today, sorely devoid of new mythos, could not produce a character of such quality and social commentary.

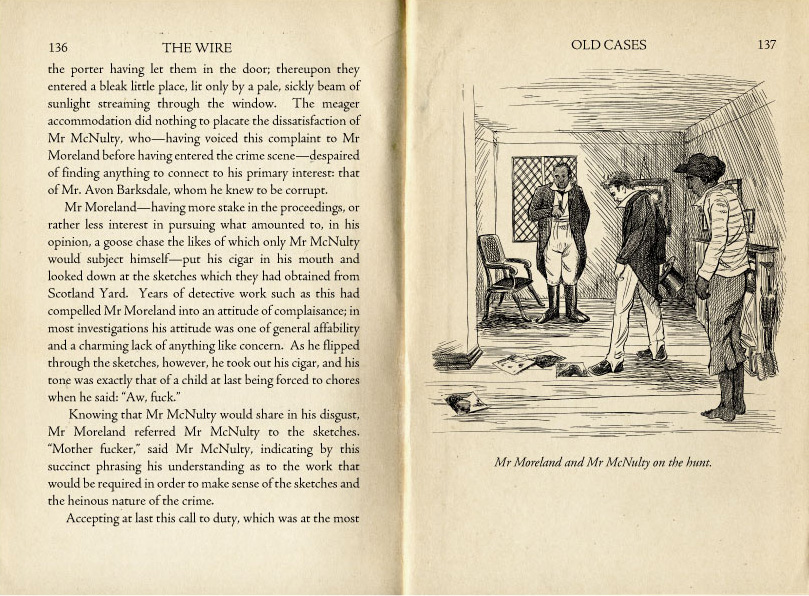

Many characters of the age pale in comparison to The Wire, but if any other deserves explicit exploration, it is James “Jimmy” McNulty. While McNulty is rich in his own right, he is particularly interesting in comparison to the viewpoint characters of Dickens. As Dickens progressed from his “picaresque” adventure-style novels to his more serious explorations of society, so too did his central protagonist evolve. And yet, instead of gaining in complexity, Dickens’ viewpoint characters dwindled—in personality, idiosyncrasy, any unique or identifying traits.

Scholars believe the passivity of Dickens’ heroes was a direct result of his shift in style and subject matter: in order to portray the many aspects of society Dickens wished to explore, in order to maintain a strong supporting cast of highly individualized characters, he believed the main character must be de-individualized. He must become a receptacle of the injustices perpetrated by society, so that the failure of social institution can be witnessed and explored as the reader identifies with the protagonist’s essential powerlessness. This is an elegant method, used to near-perfection in David Copperfield, in which the only uninteresting character is David Copperfield himself.

The Wire charted another course. McNulty is a challenging character; in the beginning, he is not easy to like. Though he is our protagonist and usually our viewpoint character on our journey through The Wire, he begins and ends on a note that is extremely morally questionable, despite a redemptive arc mid-series. We are unable to approve of his actions, unable to assimilate his qualities as our own. Yet McNulty is powerless exactly in the way of David Copperfield. He is used and exploited by corrupt social systems, institutions, or figures of power in exactly the way of David Copperfield or Pip from Great Expectations. He is helpless to incite real and lasting change, his passivity forced upon him as he constantly struggles against it, rather than rising from an internal lack of agency. It is this very struggle which endears McNulty to us, in the end.

In fact, the number one way in which The Wire differs from any other Victorian novel is its bleak moral outlook. Dickens’ works almost always had a handful of characters that were essentially likeable. In the end, the power of love and truth is borne out and the individual triumphs over the ugliness of society by maintaining his integrity. Trollope, Eliot, Gaskell, etc all wrote with this essentially Western—not to mention imperialist—mind-set. Only William Makepeace Thackeray, in Vanity Fair—subtitled, A Novel Without A Hero—presents an unrelentingly bleak assessment of society. The ending is unhappy, all of the characters flawed to varying degrees. It is significant that critics of the time chastised Thackeray for refusing to throw his audience crumbs of moral fiber.

The other comparison one might draw in examining the moral character of The Wire is the penny dreadful, Victorian booklets which exploited sensationalist drama, horror, and Gothic tradition. Penny dreadfuls were fiction published on pulp and could be purchased for a penny per pamphlet, often featuring monsters, vampires, highwaymen and crooks. Usually, these publications bear little similarity to the highbrow syndications of the time, their cliché down to an art form, their treatment of hackney topics procedural in nature.

By 1846, the time The Wire first began syndication, the Victorian audience was already familiar with an underworld of crime, the systems arrayed against it, the cop-and-robber story. But while only the penny dreadful exceeds The Wire in its depictions of violence, ugliness, and depravity of the world, these procedurals should be considered as a separate genre. They reached for the simple thrills of titillation. Meanwhile, The Wire had pretenses of social commentary, exposing deeper truths, persuading its readers not only to witness a corrupt society, but also to understand it.

Morality in Art was one of the most prevailing topics in both literary criticism and philosophy of Victorian times, propounded strongly by the art critic and philosopher, John Ruskin. Ruskin’s central argument was that one must reveal Truth in literature, but in doing so also reveal Beauty. One must present the moral beacon to which we all must aspire. One must not write without Hope. It is significant also that today, Thackeray is not charged with undue cynicism or depravity; rather, he is thought to be “sentimental, even cloying.”

Literature today is no longer concerned with morality the way it was in the nineteenth century. Unrelenting, bleak images of society are celebrated for their realism, as representations of humanity. And yet, we have very few images, representations, or new and challenging canon that captures the essential helplessness, the inevitable corruption, the deep-lying flaws of both society and humanity in the way The Wire does. Again, I would contend that such a feat could only be accomplished in the Victorian Age, through the serial format, which allowed for such layered complexity. In no other way could such a richly textured tapestry of a city be constructed from ground-level up. In no other way could the faults in the underlying foundations of society’s institutions be exposed. In no other way could our own society be held up for our examination, and found so sadly lacking.

Yet this extraordinary feat of story-telling could not have been accomplished solely by Bucksley Ogden. It would be a mistake to say that one creator or author was responsible for The Wire, when the illustrations played such an essential role. Just as Sidney Paget immortalized Sherlock Holmes independently of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle by giving the detective his famous deerstalker cap and cape, so too did The Wire’s illustrator, “Bubz” contribute to The Wire.

Would William “Bunk” Moreland be the same character without his cigar, ever-present but almost never mentioned? Would Avon Barksdale be as intimidating and yet beautiful, were Bubz not able to capture his panther-like movement, his violent grace? Could Joseph “Proposition Joe” Stewart be as memorable and endearing were he not the portly man we grew suspicious of, and somehow at last learned to love? Certainly Omar Little would not be Omar Little without his coat, like something out of the previous century; nor would he be Omar (“Omar comin’! It be Omar!”) without the weal running down his face, signifying past violence, a life of both heroic romance and mythic tragedy.

The illustrations are yet another essential element lacking from the story-telling of today. For one thing, we would not allow our cast to be represented by the “others” in our society Bubz renders so lovingly. Bubz gave us reality, and he made it beautiful. The standards of art today are no longer concerned with reality, while our fiction demands nothing but. Movies, television, the internet have all morphed our expectations, twisted and changed our visions, until we only wish to see Ruskin’s ideal: a pristine, white, purer version of ourselves.

In our age, we can never experience a modern equivalent of The Wire. We would be unwilling to portray the lower classes and criminal element with the patience or consideration of Horatio Bucksley Ogden or of Baxter “Bubz” Black. We would be unwilling to give a work like The Wire the kind of time and attention it deserves, which is why it has faded away, instead of being held up as the literary triumph it truly is. If popular culture does not open its eyes, works like The Wire will only continue their slow slide into obscurity.

Ms DeLyria and Mr Robinson are grateful to the Special Collections department of the University of Washington for generous access to their Ogden collection, including the two 1863 editions from which these illustrations were digitally scanned. Those wishing for access to more of “Bubz” Black’s illustrations may contact Mr Robinson at seanmichaelrobinson at gmail &c. Joy DeLyria can be contacted at joydelyria at gmail &c.

________

Update by Noah: The entire Wire Roundtable is here.

Update by Noah: A sort of sequel to this post is here.

Update by Noah: Joy and Sean have written an entire book about H.B. Ogden and the Wire, entitled Down in the Hole: the unWired World of H.B. Ogden— it’s out now.