For all but the most enthusiastic student of historical ballet (and for fans of Alan Moore), a passing mention of the Ballets Russes calls to mind the riotous 1913 premiere of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. Expecting classical ballet, with its tutus and fairy tale settings, the Parisian audience was caught off guard and put off their dinners by the intensely punctuated rhythm of the score; Vaslav Nijinsky’s aggressive, distorted choreography; and the brightly colored primitivist imagery of the costumes and set design.

I was taught, as a student of that aforementioned historical ballet, to interpret this aesthetic first as an effect of Nijinsky’s own mental illness and second as neonationlist entertainment targeted at the population of expatriate Russian aristocratic patrons. Both are surely true to some extent, but I was also taught to associate that neonationalism with the merchant-class Slavophilism of its original exponent, V.V. Stasov, who in the 1870s zealously opposed Western culture and idealized ancient Russia which he saw as ethnically and aesthetically pure. For Stasov, Russia belonged to the East, and the imagery of the neo-Russian aesthetic was fundamentally Asian.

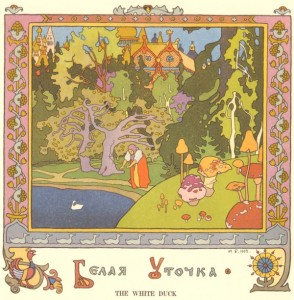

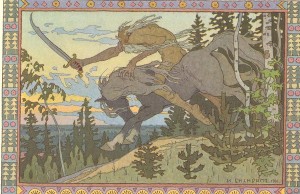

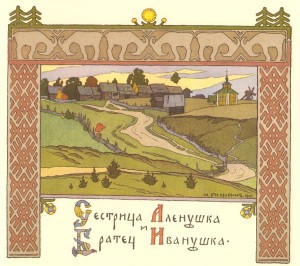

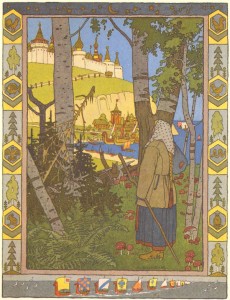

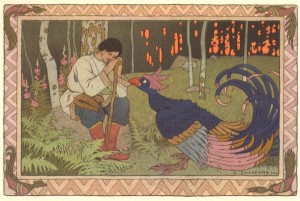

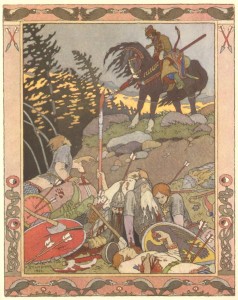

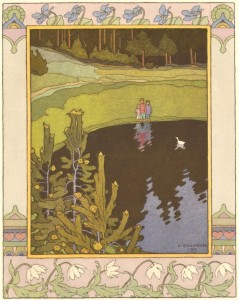

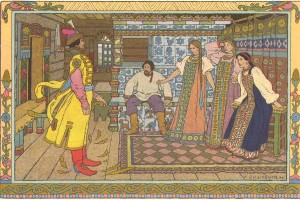

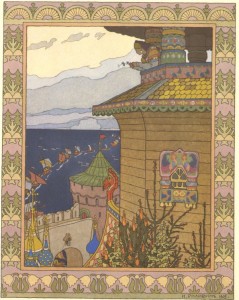

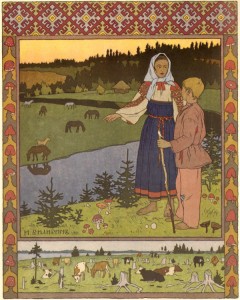

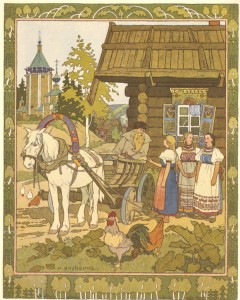

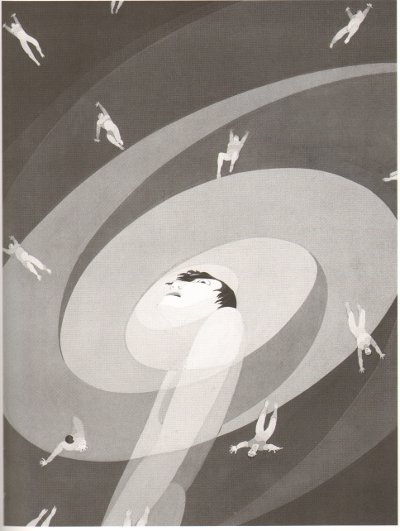

It is difficult to look at the illustrations of painter Ivan Bilibin and not see Western influences, although his affection for Japanese woodblocks is apparent.

Russian realism and the landscapes of the Peredvizhniki (particularly Levitsky) are certainly predecessors, but the aesthetic of Beardsley and Art Nouveau are palpable.

I was clearly mistaught to see so much of Stasov’s influence on the neo-Russism of the Ballets Russes. Stasov and Diaghilev, it turns out, were fierce antagonists. I think this error is an effect of oversimplification: neo-Russism did start with Stasov and was transformed by later visual artists to incorporate Western aesthetics. But dance history is closer to music history than it is to art history, and Stasov, tied to Rimsky-Korsakov and Tchaikovsky, is more important to nationalism in Russian music.

The incursion of art nouveau aesthetics likely dates to around 1894, when Princess Maria Tenisheva established an art collective on her estate, Talashkino, as part of a movement to revitalize nationalist art and preserve peasant arts and crafts culture. Aristocratic. pro-Western, and directly influenced by the English Arts and Crafts movement, Tenisheva established workshops to teach and preserve Russian and Slavic peasant techniques for manufacturing furniture, embroidering goods and making other crafts. She also set up an art school, elistist and intellectual but set against the Russian academy (which still favored the merchant-class aesthetic of the Peredvizhniki), that encouraged artists to study and depict Russian history and folklore. The style developed in these schools resembled art nouveau much more closely than any indigenous Russian folk art.

The estate became a meeting ground for a diverse group of artists and intellectuals, all of whom, including Ivan Bilibin, figured into Diaghilev’s theatrical enterprises. Beginning in 1889, Bilibin studied at Talashkino under Ilya Repin, at that time the most famous living Russian Realist, and in 1899, Tenisheva helped underwrite the journal mir iskusstva, co-edited by Diaghilev, which was the first magazine to publish the drawings of Aubrey Beardsley in Russia. In 1908, Bilibin designed the costumes for Diaghilev’s production of Mussorsgy’s Boris Gudonov.

In addition to his stage designs for Diaghilev, Bilibin is best known for illustrating Russian folktales, including famous depictions of Pushkin’s stories. In 1904, Bilibin published an essay in mir iskusstva called “Folk Arts and Crafts in the North of Russia” followed by a monograph on the same subject, based on his personal travels and investigations in the two previous years. During those travels he became interested in architecture, and continued to explore themes of folk art and architecture throughout his career. He died in 1943 during the Siege of Leningrad.

My scans of these drawings come from English translations made in the 1970s of a series of books of folktales commissioned by the Russian Department of State Documents between 1901 and 1903. There’s quite a bit of information about Bilibin online and in books and magazines — he is mentioned at least in passing in all the books I have on Diaghilev and a Google search pulls up many discussions of his art and some biography (see below) — but I haven’t been able to find anything enlightening about my editions: translated and printed in the USSR in 1976-1977, a time of detente, by Moscow-based Progress Publishing. The name of the publisher suggests proto-Glasnost, but for the time being I still have no idea why they were created or to whom they were marketed/distributed. It doesn’t stop me from enjoying them, though!

A excellent essay on Bilibin’s visual technique as well as a biography is available here.

More scans are available here.