Promises me I’m as safe as houses

As long as I remember who’s wearing the trousers

I hope he never lets me down again

Never let me down

Twenty five years ago this month, Depeche Mode was one of the biggest groups on the planet. Three men and one prop. Martin Gore, the pretty face and the songwriting talent, the man with the melodies and the ideas and the sometimes daft lyrics. Dave Gahan, the thug, the angel, the unbelievable voice, cold and controlled and icy, somehow vulnerable even in his strength. Alan Wilder, the musician, the arranger. Taking Gore’s chords and melodies and transforming them into a synthetic dance onslaught. Textures layered and melding together, the artificial alongside the organic, hook upon hook weaving through, implying and extending Gore’s harmonic structures. Fourth member Andy Fletcher? A non-musician mime that mutely stands on stage, ventrilloquizes, manages the band.

Nine years into their careers Depeche Mode embarked on a grueling 101-show international tour, in support of their album Music For the Masses. The tour culminated in a staggering show at the Rose Bowl, attended by more than 60,000 people.

The show was filmed by director D.A. Pennebaker for a documentary on the band and its fans, eventually released, along with an album of the performance, as Depeche Mode 101. (Pennebaker is probably best known for his Bob Dylan documentary Don’t Look Back, but it’s his David Bowie concert film Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars that Depeche Mode 101 most resembles)

Prior to the concert footage, the documentary gives insight into some of the on-stage strangeness of the band, and of the group’s internal politics. Off-stage, singer Gahan comes across as loutish and arrogant. Songwriter Martin Gore disappears, even when he’s on screen. Fourth wheel and non-musician Fletcher briefly makes himself useful by describing the band. “Martin’s the songwriter, Alan’s the good musician, Dave’s the vocalist, and I bum around.” And musician/arranger Alan Wilder proves him right, with little fanfare, in a sequence shot from behind a bank of keyboards, as he casually describes how different sounds are split across the instruments, and how the live arrangements are split between himself, songwriter Martin Gore, and a tape machine.

On-stage, Gahan at least is transformed, his pre-gig bluster changing into some kind of strange, thrusting energy. Unrestrained by any instrument, he stalks the stage, he shouts between singing, his voice hoarse and unrestrained. And at other moments he seems lost and weak, until the hook rolls back around and he rises to and assaults the crowd again.

At the end of their set they and their tape machine launch into “Never Let Me Down Again.” They are to a man sweaty and weary looking. Between phrases you can see Gahan’s mouth working in closeup,his face tightening, spastic, body rebelling even while his voice is restrained. “I’m taking a ride with my best friend.” The music ominous, the melody almost literally monotonous, droning. “I hope he never lets me down again.” The lyrics are stupid, real “moon in June” stuff, but they’re set in such a strange context, and the delivery is so intense, that it begs consideration.

Like many of Depeche Mode’s most affecting songs, there’s a distance, and a loneliness and despairing of communication, of being heard, of hearing. This sung by a man throwing himself about the stage in a desperate attempt to reach the audience in front of him, while the man who wrote it sings harmonies from behind his keyboard.

Gahan stops, breaths, staggers, thrusts out his hips, yells wordlessly, an octave higher than the sung range of the song.

“Let me hear you,” he screams. “Let me hear you!”

Finally he steps out onto the thrust of the stage and starts gesturing to the audience, waving his hands from side to side. And the lights come up and for the first time the camera sees Gahan and the audience together, the towering mass of waving arms rising above him, in front of him, all around him.

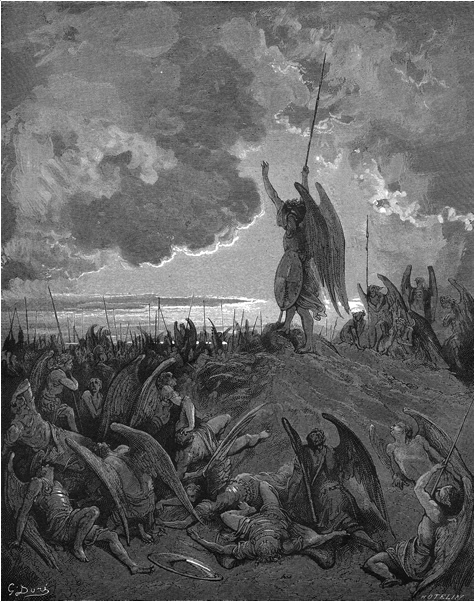

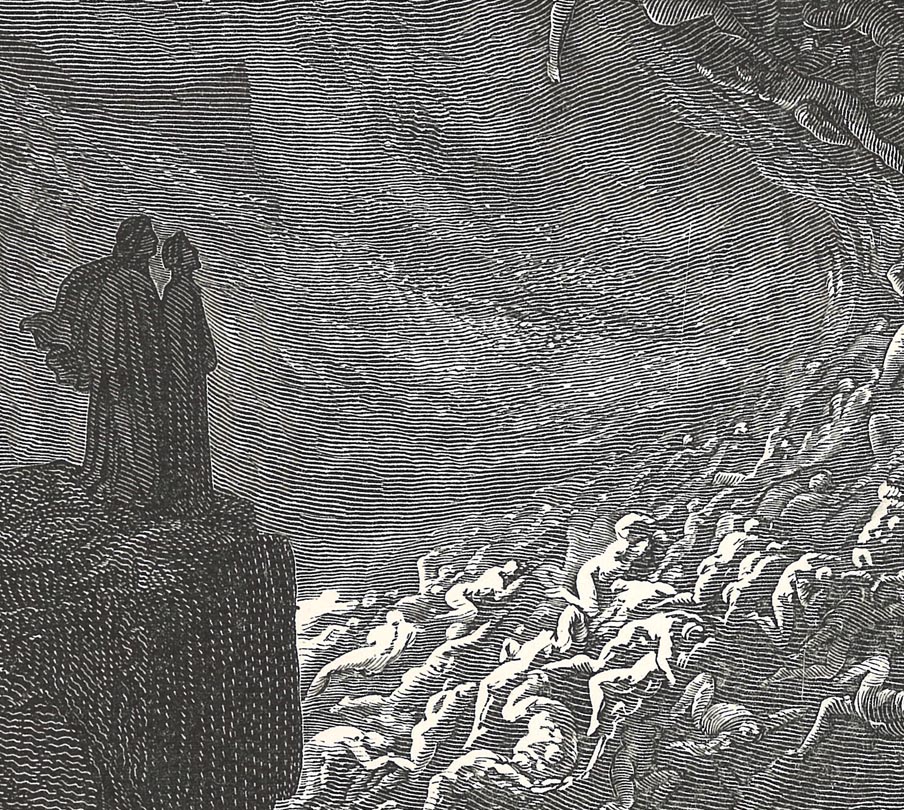

I get chills every time. It’s not just his confidence, the strutting and yelping, or the pulsing, looping chords. It’s an aesthetic reaction to him, to the whole scene, the beautiful lone figure thrust out over and surrounded by the massed crowds. It evokes the grand religious visions of Gustave Doré, particularly in his illustrations of Milton’s Paradise Lost. Of Satan, before the assembled cohort of angels, or looking out over Paradise.

Doré himself had a career not dissimilar to Depeche Mode. He was a prolific and tireless craftsman who was energetic and inventive, who relied on his collaborators, the engravers whose labors caused his pencil and wash drawings to take form in wood, to bring his work to its final form. (Like a band name represents a group of individuals, so we might think of “Gustave Doré” more accurately as a group of men, a kind of syndicate of illustrators and engravers, that shared their collective name with that of their founding member and progenitor.)

And like Depeche Mode, Doré was one of the most popular artists of his era; but critical acclaim eluded him. He was a good draftsman, critics sniffed. But. But. Was he just too well-known to be well-respected too? Or too well loved?

Not to mention the “illustrator” issue…

You see, the past two hundred years of aesthetic criticism have not been kind to function.

It’s why “craft” is a pejorative. It’s why design forms its own sub-category of visual art, related, somehow, to the field, like a second cousin once removed. It’s why soap operas and romance novels and video games and quilts and pottery and wood carvings and, hell, flower arrangement have been kept at an arm’s length from Art, an asterisk at best. Function implies craft. Function precludes intelligence, the demands of function displacing the desires of author.

Utility is at the heart of the critical attitude towards dance music.

Like pornography, you can evaluate dance music by the bluntest measures possible – it’s efficacy. Did you dance? Did other people dance? How many other people? How vigorously? The crassness of this measure tends to ward off deeper examination.

And that could be why Depeche Mode will likely remain a band well loved, but largely un-examined. Why some of the most interesting music made in the past four decades could be relegated to roller skate rinks and cut-out bins.

And when I squinted the world seemed rose-tinted

And angels appeared to descend

To my surprise with half closed eyes

Things looked even better than when they were opened