This first ran on Splice Today.

________________

I was both surprised and delighted 12 Years a Slave won the Oscar for Best Picture. Some, however, were gnashing their teeth. Jonathan Rosenbaum, for example called 12 Years “an arthouse exploitation gift to masochistic guilty liberals hungry for history lessons,” while John Demetry at CityArts argues that the film denies Northup specificity or consciousness, turning him into “a cypher representing Black hopelessness.” Both argue that other films are more insightful and respectful in their treatment of slavery—and in particular, both mention Charles Burnett’s 1996 film Nightjohn, which has almost no popular profile and which, like 12 Years, was created by a black director.

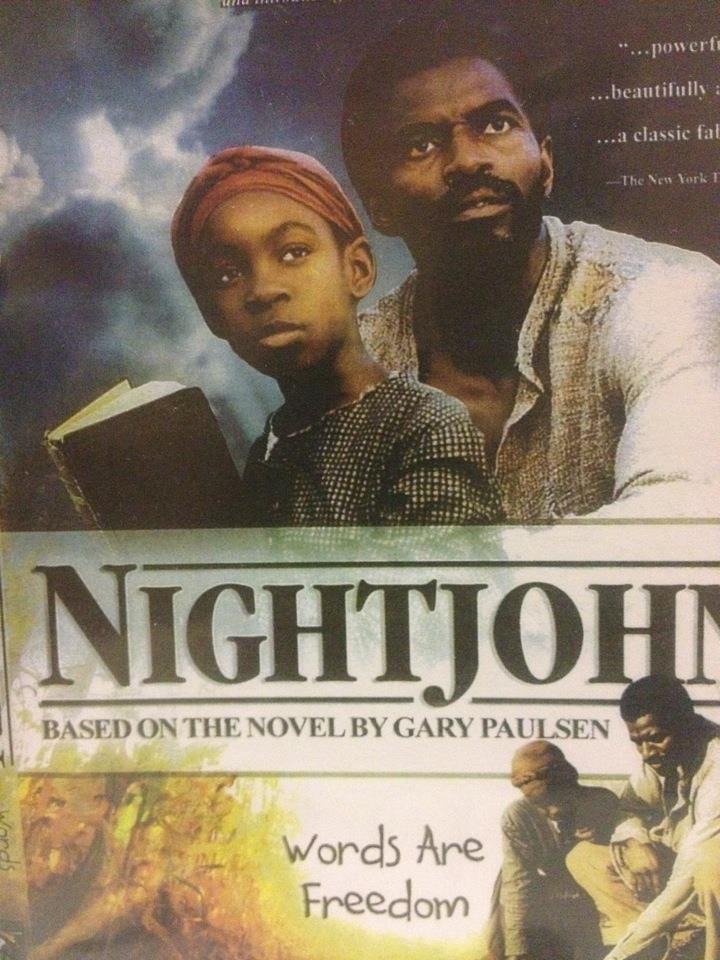

There’s no doubt that Nightjohn is distinct from other slavery films in a number of intriguing ways. Originally screened as a TV movie on the Disney Channel, it embraces the smaller-scale, living-room format. The plot centers on Sarny (Allison Jones), a young, avidly curious girl whose life as a slave is transformed by her owners’ purchase of Nightjohn (Carl Lumbly), who offers to teach her to read.

Putting literacy at the center of the story allows Burnett to avoid many of the standard slavery tropes. Though there are violent scenes in the movie, the main drama is not around physical endurance or resistance, as in Glory, Amistad, 12 Years, or the less well-known Sankofa. Instead, the drama is about intellectual achievement as a reclamation or assertion of self. Reading means that Sarny can write passes to help friends escape; it means she can manipulate white people to her own advantage and to the advantage of her community. Knowledge is power, and if slaves can learn to read, they can obtain that power.

Nightjohn, a runaway who had made it to the North, returned into slavery to teach other slaves to read. This recalls Beverly Jenkins’ Indigo (also from 1996), in which the protagonists’ father, a freeman, agrees to become a slave to marry the woman he loves. In both cases, the moral is not self-abnegation, but rather self-assertion—an insistence that slavery is not the most important truth, and does not define black people. They are not just victims, but human beings who, even in extremis, can pursue human goals such as knowledge, teaching, or love.

Yet, for all its focus on intellectual development, the interiority that Nightjohn imagines is an oddly public and dramatic one. Sarny’s lessons, for example, coalesce all at once while she is in church reading the Bible—suddenly the individual letters fall into place, and ta-dah! she can read. The moment is so powerful that she starts to cry, and the white minister thinks she’s been saved. “Yes, I am saved,” she agrees when asked, and is then baptized. The scene is equates, or conflates, the ability to read with religious salvation or awakening, making the attainment of reading a kind of mystical right of passage, complete with ceremonial trappings.

Along the same lines, the climactic scene of the film occurs, again, in church, in front of the entire community. Sarny’s owner, Clel Waller (Beau Bridges) threatens to start shooting slaves until one of them tells him who has written the passes for two escapees. Sarny defuses the situation by obliquely threatening to expose the fact that Clel’s wife has been committing adultery with the town doctor. Sarny knows about the affair because she was the one who carried notes back and forth; her ability to read gives her a weapon.

These scenes are meant to demonstrate that private knowledge is not merely private; learning to read for the slaves is a political act, with political ramifications. And yet, those political ramifications are actually somewhat undermined by the rank implausibility of the set pieces. People don’t actually learn to read all at once. Blackmail can be effective if applied cleverly and surreptitiously, but flaunting his spouse’s adultery in the face of a man with a gun pointed at you is not likely to result in a positive outcome. In his enthusiastic review of the film, Jonathan Rosenbaum characterized the movie as a kind of “fairy tale.” But the departures from realism here feel less like magic or dream logic, and more like standard film contrivance—drama for the sake of drama, and/or for the sake of communicating the requisite moral at sufficient volume that it can be deciphered in the nosebleed seats.

The didactic staginess is perhaps appropriate for a film about teaching. But it’s also somewhat disappointing, not least because it’s so familiar. Movies about slavery—whether Amistad or Glory, 12 Years a Slave or even Django Unchained—all have about them a sense of the educational spectacle as growth experience. There are probably a number of reasons for this. Films (even TV movies) are wedded to their status as events; it’s hard for a movie to resist the urge to be larger than life. Slavery is so intimately linked to ongoing racial disparities, and so relatively little explored on screen, that the impulse to say something definitive must be nearly overwhelming. Whatever the combination of factors is, though, the fact is that most movies about the subject are couched to some significant degree as “history lessons,” to use Rosenbaum’s dismissive characterization of 12 Years. And as a result the people in the films tend to turn into tropes, or icons, or curriculum enhancements. Like Nightjohn telling Sarny that the “A” is standing on its own two feet, the symbolic message can erase individuality and ambiguity, so that the letter means its image rather than all the things it can spell.