A great deal has been said and written about the lying our public figures do, recently. After the “misremembering war events” scandal that brought Brian Williams down, Bill O’Reilly has been subjected to scrutiny over his claims of witnessing combat during the Falklands War. This past week, Secretary of the VA Bob McDonald has been criticized for claiming to a homeless man to have been in Special Forces – he was not. Chris Kyle, of course, is remembered as a hero by many, despite having a demonstrable record of lying about events (much of this occurred post-moral injury, when Kyle was suffering from PTSD). Hillary Clinton lied about being shot at by snipers and is polling stronger than any other potential Democratic candidate for President in 2016. Army veteran (who should goddamn know better) and Democratic Senator Richard Blumenthal lied about serving in Vietnam. Republican Congresswoman and military veteran (who should also know better) Joni Ernst has received criticism over calling herself a “combat veteran” using a very broad definition of “combat.”

People lie. There seems to be a fairly broad consensus along the political spectrum that politicians lie a great deal – whether you believe that “your” people lie less or less harmfully probably goes a ways toward establishing how one votes in an election (having become fairly disillusioned, I recently registered Independent, abandoning the Democratic Party). This explains why a state populated primarily by Democrats would elect Richard Blumenthal over his Republican rival, despite his – well – lying about combat. This explains why Democrats are happy to forgive Hillary for lying about being in combat (misremembering is not something that happens when you’ve been under sniper fire once), and why Republicans think that Joni Ernst should be given the benefit of the doubt for her admittedly less egregious (but still fairly stupid) description of having been in combat, when she was posted to Kuwait, quite far from combat. In this case, her description of herself as a combat veteran is less annoying than her repeated and ongoing defense of that untruth.

I should also point out that most combat veterans, myself included, don’t feel that combat experience gives one special insight about life that one would covet, save that combat is a situation to be avoided at all costs. When one considers that politicians who experienced combat throughout history continued to encourage or abet warfare, it’s impossible to conclude that there’s any real utility to combat as a morally didactic lesson, save potentially on an individual level.

It’s slightly different with journalism, in that, technically, in order to call oneself a journalist it’s important that one adhere to certain unwritten but widely-obeyed rules: don’t get involved in a story, don’t plagiarize, don’t lie. O’Reilly has already said he’s not a journalist, and has no credibility with people who aren’t a certain type of conservative – this seems to have insulated him from the brunt of the fury that resulted in Brian Williams’ demise.

And that’s fascinating! Williams, by defining himself as a journalist, made himself more vulnerable to truth-criticisms from people that watch his program than O’Reilly. (For the record, I was fine with him continuing as an anchor – anyone who thinks journalists, who are human, don’t directly or indirectly lie [routinely] should be banned from ever voting)

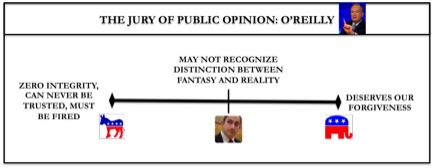

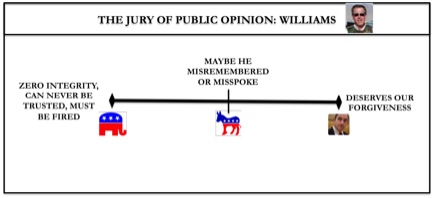

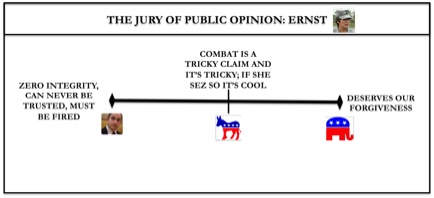

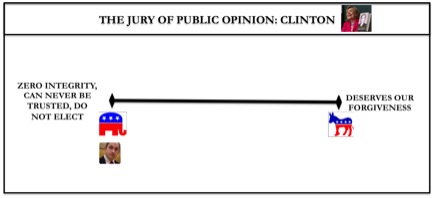

I wanted to compare how various public figures seem to be judged on their military lies, so I threw together a basic chart and mapped public perceptions of journalists and other truth-tellers onto it.

What I found was… well, not shocking at all, really. O’Reilly’s posse sticks up for him and he won’t be fired despite having lied I’ve put myself on the spectrum (right in the middle there) because if one is going to make a claim about a thing, well, have the sack to tell others where you fall.)

And Williams, who has a more discerning audience that is willing to entertain shades of gray, suffers by comparison:

And just to see how that works out with politicians – there’s the Republican case of Joni Ernst, who has claimed (playing off a credulous public’s unfamiliarity with battle and sympathetic media) that she was in combat because she was in a combat zone. Which is exactly like me saying I got the shit kicked out of me once at a bar because there were a group of guys at the end of bar muttering and looking over at me and I was really worried about getting the shit kicked out of me. Someone who had once gotten a severe ass-whipping would probably take issue with my claim, as I do hers. Let’s see if she’s going to be fired or held to account or not (remembering that this is a question of whether or not someone’s worthy of the trust, confidence, and respect of the public):

Looks like Ernst is gonna be okay – the Republicans have her back (not surprisingly), and the Democrats / media don’t feel like evaluating her claims on their merits, and calling a liar a liar. Of course, if they did that with Ernst, they’d have to do that with Hillary Clinton, the putative fundraising frontrunner for 2016, and – don’t forget – maybe our first female president. What does it matter if she happened to lie about – well, anything?

I’m also down on Clinton because of that “we need to go into Iraq” thing she did, which if anyone remembers, was basically responsible for all the horrors we see in the Middle East today – a place that used to be filled with sensible dictators who were amenable to bribes and arms deals and could be relied on to limit their war crimes to 25,000 or 30,000 dead every decade – a tiny fraction of the dead since we became involved over there. But it looks like she’s going to walk, too.

In conclusion, the lies that get told to us by our political leadership don’t seem to matter as much as the lies that are told by people who call themselves “journalists,” which may or may not involve abiding by a set of agreed-upon rules to tell stories in a certain way. And while “liberals” or “progressives” tend to evaluate journalists and people outside their group more generously than “conservatives,” both groups are equally bad at applying rigorous scrutiny to their politicians.

So it goes.