A few books by some of comics’ (male) best and brightest of several eras. Some of these have been out for awhile, but I only just got around to them.

_____________________________________________

Jon Fury in Japan

Alex Toth’s only extended stint on a continuity strip was done for his post newspaper when he was stationed in Tokyo in the Army in 1955. Jon Fury was his first effort writing for himself. While he could brilliantly interpret the scripts of others, Toth faced nearly insurmountable difficulties to construct his own. He tried to emulate Milton Caniff’s narrative mastery, but he certainly didn’t “get” one of Caniff’s greatest assets: his use of female characters of depth and agency. Toth is strictly old boy’s club, but truthfully his male characters are not much better defined. The storylines feel forced and they are riddled with overlong exposition to the extreme. Despite these drawbacks, his art is highly developed and constrained only by the sheer weight of text; these are dynamic, elegantly designed episodic pages in the Caniffian Sunday format. More than any of his contemporaries, Toth reached for clarity of comics expression and here he exhibits his mature style in a serialized form, where weekly deadlines dissolved the hesitations dictated by his perfectionism.

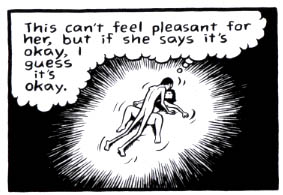

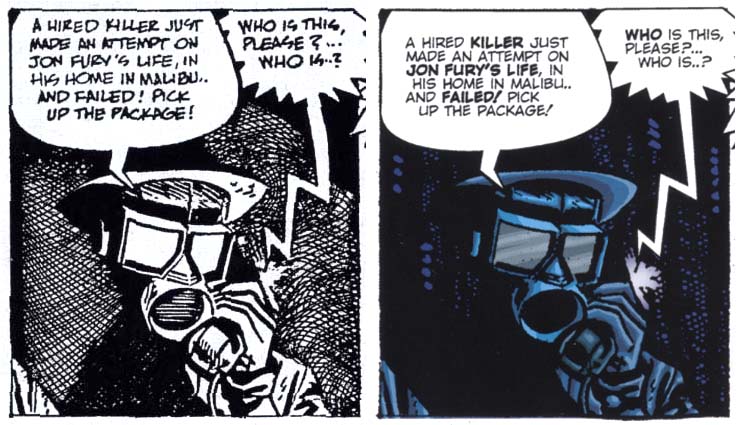

The late Toth did the work for black and white reproduction and so that is how it is seen in IDW’s recent Toth bio Genius, Isolated. The original art was done in a process similar to mimeograph, basically drawn directly on waxy plates, which quickly begin to degenerate in the process of printing, even in such a small print run as these strips had, with the result that a complete pristine set is probably impossible to put together. The art restoration in the panel below from the slick color comic book version, Jon Fury In Japan, is definitely better than it is in IDW’s hardcover bio. In both recent versions, there are many minute amendments to the drawings by other hands; these are more pronounced in the color comic.

One panel’s restorations: left, from IDW’s version, right, from the comic.

IDW’s reconstruction of Toth’s original lettering of the later pages is readable, but in the comic book version, Toth’s lettering has been removed on most of the pages, which are re-lettered with a cold and inconsistently scaled digital font. This may read easier, but the artist’s hand is lost. And, emphasis via bold type has been added to Toth’s dialogue. As well, if art done for black and white must be colored, Toth’s is better suited to flatter hues, a four color comic book or Sunday strip-like color. The example shown above is atypical; overall, the too-plastic fades and color modeling feel anachronistic to the period piece. Plus, although effort is made to color the protagonist as a native American, many color decisions are counterintuitive, for instance in the pink jacket of the thug also seen on the cover.

Granted, the pages needed repair, but work so pared to its essence is subverted by overt interference, much less the overkill of the comic package. Fortunately, Jon Fury in Japan also contains Toth’s final interview, significant for its emphasis on his animation career. Other than a few questionable photos, this has a good selection of panels by Toth and his influences and the coloring imposed on these is more appropriately restrained. (Paul Power, $11.00)

_______________________________________________________

“Red Tide” in Dark Horse Presents #3

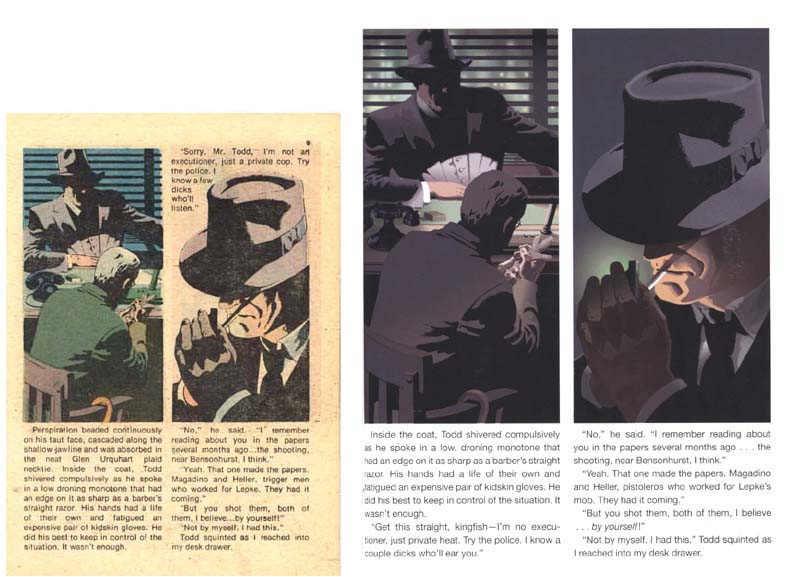

Chandler: Red Tide was released to the book trade in 1976 as the first American original full-color mass-market graphic novel. It represents Jim Steranko’s longest, most ambitious auteur effort in the comics medium to date. The two-panel-a-page layout with dual type blocks underneath is constructed in such a way as to be unusually immersive; in the act of reading, the obviously separated art and text come to simultaneous apprehension. The art was drawn in pencil without feathering and with minimal holding lines; Steranko’s excellent comics-like color separations often define the forms. The original book has a pulpy chiaroscuro feel that echoes the great noir films to which the story effectively pays homage. The representations are likewise mostly typical of the hard boiled dick genre; for instance, the protagonist and the leading lady have a prior history and her passion is reignited when she senses “something more than anger behind” his slap. On the other hand, there are appearances by a lesbian cab driver.

A reissue of Red Tide enhanced by the author has been looming for years and now here’s a taste with an excerpt of the first chapter, in Dark Horse’s slick house anthology title. Steranko expands the possibilities of digital color while reiterating that cartooning devices like holding lines, heavy outlines developed to contain badly-registered color inks, are no longer essential with tight full color printing. He transforms and rebuilds his images into layered digital paintings that greatly resemble the airbrushed Art Deco graphics and advertising art of the period depicted. There is an impressive depth to some of the images that far outstrips what he was able to do in the method of the first printing. He is able to amplify the visual connection to Chandler’s milieu with contemporary tools while exploring the intrinsic qualities of those tools with imaginative verve.

Perhaps this new version puts undue emphasis on the images, in terms of the time involved in the readers’ perception of them relative to the reading time of the text. The expanded density of the art as well as the altered justification of the type blocks conspire to disrupt the 2/1 art-to-type ratio which is key to Steranko’s immersion formula, one of the most important virtues of the book.

Still, any new (or newish) comics by Steranko are welcomed. What he did with these pages is very interesting and no doubt the completion of the augmented edition will be impressive. I can see the amount of time and effort he has to put in to finish the whole book to the level of this excerpt though, and so perhaps in the meantime, Red Tide can be put out in a nice facsimile edition so it can get the attention it has long deserved and he can finish this new enhancement as he will, without pressure. (Dark Horse, $7.99)

_______________________________________________________

Is That All There Is?

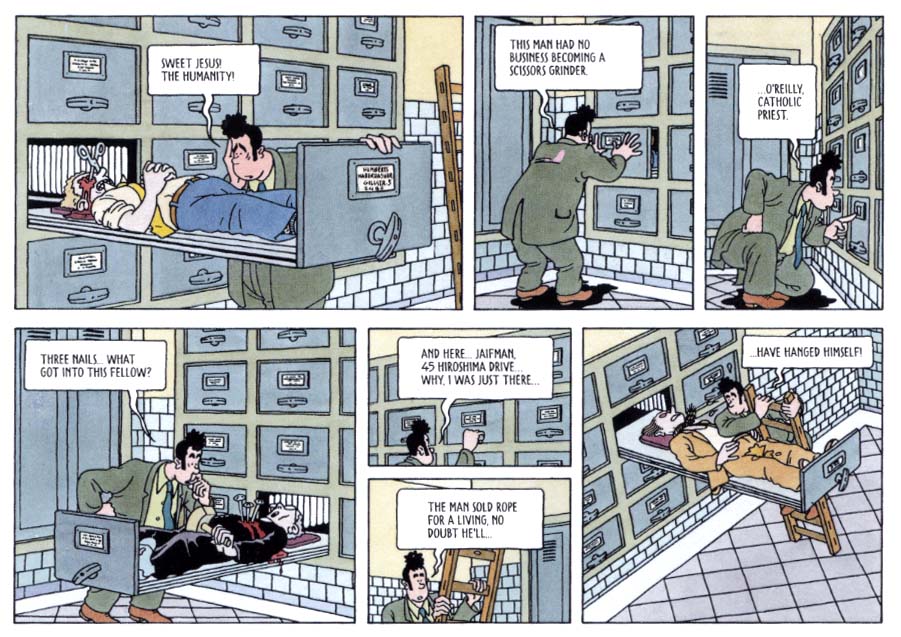

I recently read a review of Joost Swarte’s collection of most of his comics work that complained of the scale of this small hardcover, but I think it has a jewel-like quality. It is a beautiful little book that one can delve into periodically to simply enjoy Swarte’s exactingly rendered, beautifully colored comics pages.

The art is the thing here. While there are some engagingly animated sequences, the stories seem mostly clever, sometimes flimsy cause-and-effect variations created as supports for Swarte’s meticulous cartooning science. As with Toth, the more interesting aspect of the work is the way that the art manifests the ideas, such as they are—Swarte is a master of page architecture and image construction and he also has a tendency to reflexively expose his practice, which is why he is so revered by comics structuralists such as Art Spiegelman. The Franco-Belgian clear line derived from Herge and his forms of representation have their most refined outlet in Swarte’s short absurdities, reprinted from his Modern Papier and a host of other comics periodicals here and abroad including Metal Hurlant, Charlie and Raw. (Fantagraphics,$35.00)

_______________________________________________________

Madwoman of the Sacred Heart

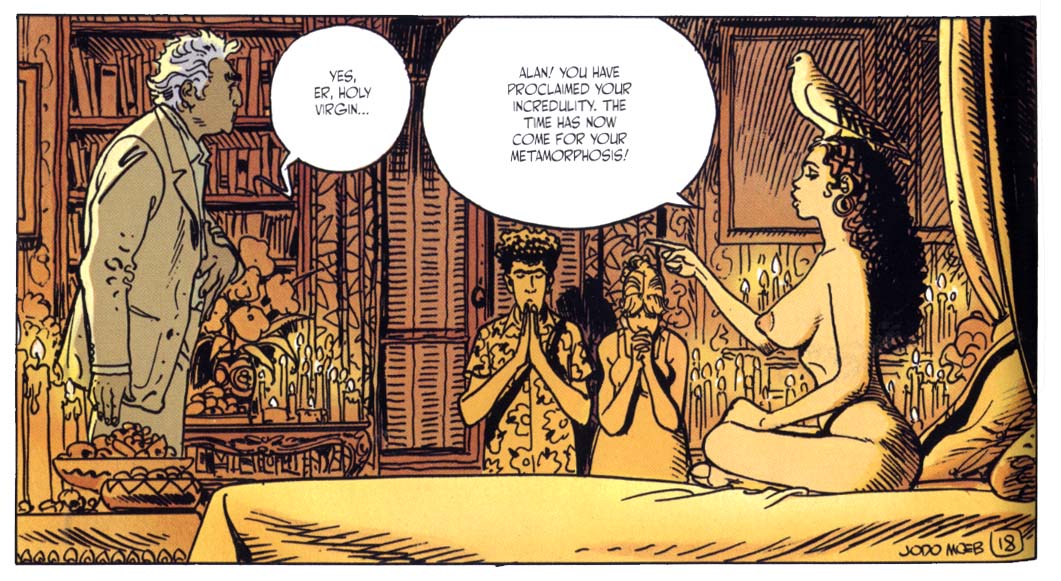

I love the recent translation of Alexandro Jodorowsky and Moebius’ Madwoman of the Sacred Heart. A black and white version published in the USA in 1996 contained only the first two parts (it was completed in 1998). This full color trade paperback of the complete Madwoman shows the best efforts of both men, far outstripping their earlier collaborations on The Eyes of the Cat and The Incal trilogy. Jodorowsky’s scenario is hilarious, an incisive and compulsively readable satire of sex and religion, for starters, that offers Moebius the opportunity to draw his single most immersive work of comics storytelling. The seemingly effortless flow of Moebius’ panels here rivals the reduced clarity of the best of Alex Toth’s 1950s Dell comics.

The book is a prime example of text and art reading together as equal forces at the service of the narrative. There are plenty of places for writer and artist to shine, but one is rarely brought out of the narrative to marvel at the construction, even when it frequently veers to philosophical discourse or transcendent visualization. I usually complain if Moebius does not do his own coloring, but here several colorists did an effectively punchy but tasteful, organic job of it; even if it is digital, most of the color looks like painted bluelines.

My first impression was that it takes some considerable suspension of belief to accept that the Heinleinesque protagonist (who is apparently an amalgam of the authors) holds such sexual magnetism for beautiful young women (and men), but Marguerite informs me that the French have such high regard for their intellectual heroes that an elder philosophy professor from the Sorbonne might indeed be considered quite sexy. At any rate, Jodorowsky and Moebius’ trangressively libidinous epic is played out so beautifully, without ever feeling forced, that the ride is taken willingly and has many rewards. (Humanoids,$24.95)

_______________________________________________________

Paying For It

Chester Brown has represented freedom to me for such brilliant improvisations as his original complete version of Ed the Happy Clown and The Little Man and I also admire his Biblical adaptations and Louis Riel—but Paying For It is a constricted, joyless business. As a comic by Brown this has a certain mastery of form and the art is technically as good as ever, but the reader barely notices it, because to a large degree the art serves only to drive the reader through the book. It is primarily a reading machine and one is driven to focus on what is being said in Chester’s voice in the form of a memoir.

I would have little interest in reading such a john’s-eye view in prose form and as johns go, I am not made to feel sympathetic to Brown. He frets briefly about the possibility of an undercover sting, but where prostitution is a crime, it is one that prostitutes are prosecuted for, not johns. He worries a lot about being robbed and the expense, the money. He is concerned about girls that look too young, but for his liability alone, one assumes, because he can hardly tell if they are of the age of consent, or not: he declines to have sex with any women above a very young age, although he himself is forty and stretched a bit tight, at that. I’m no oil painting either, but really, it can’t be much of an aesthetic experience for the women that have to deal with him and they could be his daughters.

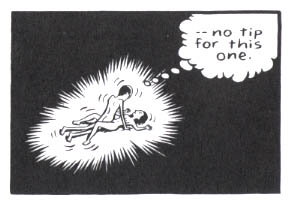

The exhibitionism here is similar to his ruthlessly honest explorations of his teenage years in the later Yummy Furs, but here, the whole gives off an aura of creepiness on the part of its author. Sex is to Brown reduced to a physical function, it’s all about him and his pleasure or release. Brown doesn’t draw the faces of the prostitutes he visits—well, except for panels such as those I scanned. Ostensibly for the reason of preserving their anonymity, his ploy effectively dehumanizes and reduces them to 3-dimensional versions of the bodies of the Playboy playmates he masturbated over in his youth. He essentially jerks off with real people! Actually, drawn as cartoons, they again become 2-dimensional and there is little variation to distinguish the progression of faceless women at all.

I don’t dispute the case he makes in his comic and annotations for the escorts, but the show of concern he makes for their circumstances. One gets the sense that Brown wouldn’t care about or do art about any of it, if he wasn’t trying to justify his involvement. In practice he seems devoid of empathy or affection. We are treated to many panels drawn from an overhead, Brueghelesque perspective of Brown banging away hell-bent for leather, getting his money’s worth. He can motivate himself to solicit prostitutes and then do the years of work involved in a graphic novel and share himself with the world, but he can’t get it up to fight for love. All the effort that goes into a relationship…who needs it? In this case, listening to his friends might have helped; they all try to give him good advice. But, as his pal Seth says, “Chet’s a robot.”

He’s also a cheapskate: he’s not the one “paying for it.” We who buy the book are and in addition, this thing was subsidized by generous grants! It’s fucking depressing. (Drawn and Quarterly, $24.95)

_______________________________________________________

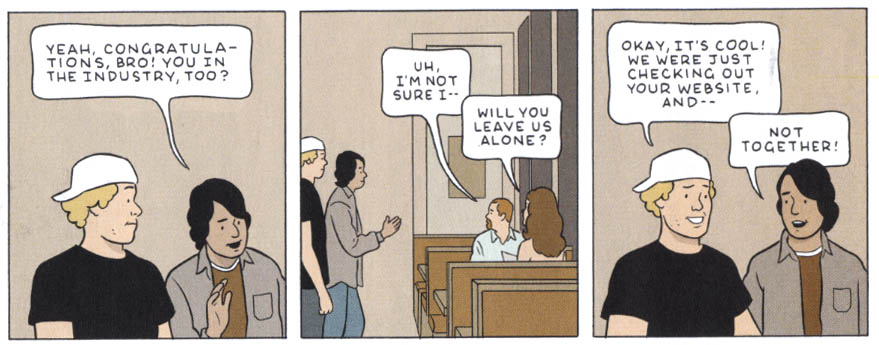

“Amber Sweet” in Optic Nerve #12

Adrian Tomine uses his work to thoughtfully explore multicultural and interpersonal relations. His work exemplifies the reader immersion and simultaneous cool remove that a refined visual orchestration can lend to a narrative. “Amber Sweet” is an expanded version of Tomine’s great piece from the massive Kramer’s Ergot #7. His concise and elegant drawings and color give a measured, airy tone to his ironic tale of the torments endured by a young woman because of her resemblance to a well-known porn star. When they meet, the contrast is telling: the real Amber is self-possessed; she handles her admirers with a blithe “Hey! What’s up?” or poses with them for a picture, butters them up a bit and then brushes them off. It is her choice to do what she does, but her choice has inadvertently isolated her doppleganger, who is continually harrassed by aggressive men. This destroys the relationships of “not-Amber,” whose eventual distrust of all men is often justified. This is underlined by Tomine in the scene below, in which two young men impose themselves upon her, denying the implications of their simultaneous wanking while assuming her companion’s complicity in their homosocialism. (Drawn and Quarterly, $5.95)