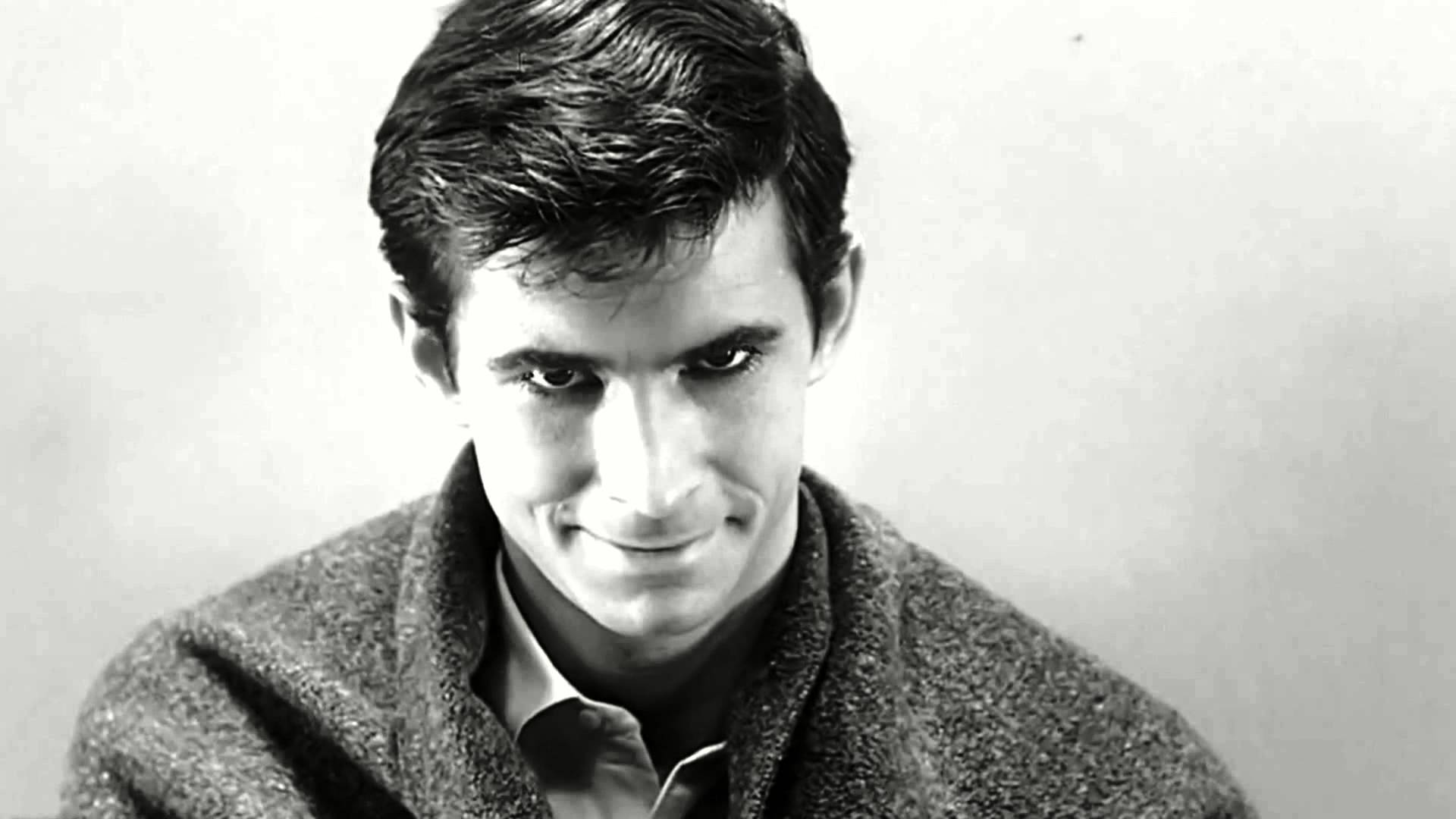

The most famous attack by a trans person on a woman in a bathroom occurred in 1960. Norman Bates, dressed as his mother, murdered Marion Crane in the shower.

That didn’t really happen of course. There aren’t any real incidents of trans women assaulting people in the bathroom. There’s only fictions—fictions which, as Psycho demonstrates, go back a long time.

The fiction is based, supposedly, in a need to protect women. North Carolina legislators insist that women are at risk from deceptive, sneaky rapist men in female garb. Psycho, though, suggests that it’s that narrative itself that’s deceptive. Hitchcock’s film famously leers at Marion, from its opening dramatic shot from the city skyline and into her apartment to view her afternoon tryst, all the way to the moment when Norman peeks at her undressing in her apartment through the hole in the office wall. The thrusting, stabbing shower scene is the climax of an overheated fantasy; voyeurism becomes imagination becomes sex becomes violence. Marion, the thief, the tease, gets what she deserves at the business end of the male gaze.

The brilliance of Psycho is that that male gaze isn’t male; Norman’s murderous impulses are because he’s a woman, not a man. The violence against women is blamed on femininity; a real man would not stare at Marion like that and then do what Norman does. Norman kills, but only because he’s really his mother. Women commit violence against women. They bring it on themselves.

The film itself claims that none of this has anything to do with trans people. The psychiatrist at the film’s conclusion carefully explains that Norman is not a real transvestite.But as Jos Truitt explains in her brilliant analysis of the Psycho-indebted Silence of the Lambs, the refusal to let Bill or Norman define their own gender identity is part and parcel of transphobia and transmisogyny. Psychiatrists and psychologists and scientists always take it upon themselves to decide who gets to be really trans, who gets to really be a woman, and who gets to really be a man. Bill and Norman are such deceivers that they deceive themselves; they are so twisted and monstrous they cannot even identify themselves. Only the objective observers—the legislators, the scientists, and alas, often, the feminist theorists—really know who is who and what is what. Norman identifies as a woman; woman are irrational and untrustworthy; therefore Norman is not really in a position to know whether she’s a woman, and is instead a man. Misogyny denies women the ability to claim their own identity. Only men, or femininity-rejecting TERFs, can do that for them.

Psycho isn’t real. Its hatred is directed at characters, not people; no actual women were harmed in the making of this film (as opposed to in The Birds.Psycho

is all in good fun—and it is fun. Sadistic fantasies are exciting and sexy; blaming women for what you want to do to them is clever and exhilarating; defining other people, bending them to your own prejudices and congratulating yourself on your perspicacity, is godlike and satisfying. The legislators in North Carolina get to revel in their fantasies of abusing women, while self-righteously saying the women they’re abusing are the abusers.

Prejudice functions as an exploitation film. People sometimes hate because they’re afraid, or because they’re misguided, or because there’s something to be gained politically. But they also hate, like Hitchcock, because hurting people is fun. There’s a rush in peeping into that secret space, and imagining, and committing, all those filthy acts in the name of someone else.