That’s what Alan Moore told a recent interviewer. “I don’t think the superhero stands for anything good,” he said. “They were originally in the hands of writers who would actively expand the imagination of their nine-to-13-year-old audience.” But since all they do nowadays is entertain 30-60-year-old “emotionally subnormal” men, Moore considers superheroes “abominations” and their continuing dominance “culturally catastrophic.”

This from a self-professed anarchist who considers the shooting of government leaders a “lovely thought.” Little wonder his first superhero was a terrorist.

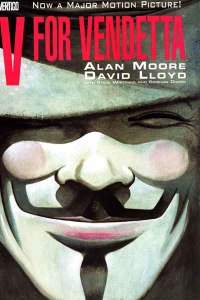

Moore and artist David Lloyd started V for Vendetta in 1981 for England’s since defunct Warrior magazine. I started reading it when the series moved to DC in 1988. I was 22, Moore’s age when he first conceived a story about “a freakish terrorist” who “waged war upon a Totalitarian State.” But it was Lloyd who transformed Moore’s freak into “a resurrected Guy Fawkes, complete with one of those paper mâché masks in a cape and conical hat.”

Their plan was to create “something uniquely British,” and, sure enough, the Fawkes reference meant absolutely nothing to this Pittsburgh-born college senior. When I’d read The Handmaid’s Tale the year before, I though Margaret Atwood was forecasting an original future: “when they shot the president and machine-gunned the Congress . . . The entire government, gone like that.” But Fawkes beat her by almost four centuries.

I didn’t read up on the Gunpowder Plot till I was a student teacher prepping Macbeth for a class of tenth graders. Shakespeare staged his tragedy of a regicidal anti-hero after Catholic terrorists tried to blow-up King James during the 1605 opening of Parliament. They’d rented a storage space under the House of Lords and crammed in three dozen barrels of gunpowder. Fawkes was arrested before he could light the fuse, tortured into betraying his dozen co-conspirators, tried, hanged, and his body displayed in pieces as a warning to sympathizers. He was still in prison when London lit bonfires in celebration of the King’s survival, and Parliament later declared the anniversary an official holiday, complete with fireworks and newspaper-stuffed “guys” set ablaze.

But hatred is a funny thing. Somewhere along the line the point of all those celebrations got hazy. Guy Fawkes Night lost its official standing in the 19th century—around when penny dreadful writers were converting England’s most abominable traitor into a romantic hero, a conspiracy Lloyd happily joined. “We shouldn’t burn the chap every Nov. 5,” he told Moore, “but celebrate his attempt to blow up Parliament!”

I want to say the American equivalent would be championing John Wilkes Booth or Lee Harvey Oswald, but Fawkes’ rehabilitation might be possible only because his assassinations failed. Benedict Arnold could be closer—except no one remembers what treason he was planning (and even if you do, surrendering West Point to the British just doesn’t have the same audacious charm).

So Lloyd wanted to “give Guy Fawkes the image he’s deserved”—but I’m not sure Moore was fully committed to the plot. Despite his anarchist rhetoric, he doesn’t “believe that a violent revolution is ever going to work,” and he doesn’t hide his freakish terrorist’s violence under POW! and BAM! bubbles either. It was Lloyd who banned the sound effects (along with thought balloons—probably the most important moment in Moore’s development as a writer), but Moore’s dialogue complicates the violence Lloyd renders otherwise bloodless:

“I’ve seen worse, Dominic, physically speaking. Like I say, it’s the mental side that bothers me . . . his attitude to killing. Think about it. He killed them ruthlessly, efficiently, and with a minimum of fuss. Whatever their faults, those were two human beings . . . and he slaughtered them like cattle!”

The terrorist also enters quoting Macbeth, the monstrous anti-hero Shakespeare’s audiences (including King James for whom it was commissioned) would have linked to Fawkes. Moore’s Chapter One title, “The Villain,” is a bit of a clue too. V goes on to murder and maim his way through some thirty more chapters, but the part that troubled me most at the time was the psychological torture he inflicts on Evey. Yes, he rescues the damsel from a back alley rape in standard Batman fashion, but then he dupes her into believing she’s been imprisoned by the fascist government, shaves her head, starves and waterboards her, all in the name of . . . what exactly? By the end Evey is a good little Robin, taking on her mentor’s mission, but there’s more than a whiff of Stockholm syndrome between the panels.

“The central question is,” Moore says, “is this guy right? Or is he mad? I didn’t want to tell people what to think, I just wanted to tell people to think and consider some of these admittedly extreme little elements.”

Which, by the way, is a pretty good example of using a superhero to actively expand an audience’s imagination.

Meanwhile, Guy Fawkes keeps adventuring. The “hacktivist” network Anonymous adopted Lloyd’s Fawkes mask for their 2008 Scientology protest—which they then carried over to Occupy Wall Street and, most recently, a worldwide Million Mask March held on Guy Fawkes Day to protest government austerity programs. The group’s anti-corporate message, however, gets a bit hazy once you know Time Warner owns the copyright on the mask (via DC I assume) which are manufactured in South American sweatshops and earn the company a killing on Amazon.

Something to think about, Moore might say.