This first appeared on Splice Today.

______

As a critic, I not infrequently know the artists or writers whose work I write about.

If you’ve been following the #gamersgate controversy at all, you know that some people think that this is really wrong. “Journalistic ethics!” people shouted over and over on twitter. It wasn’t exactly clear what they meant by this, but critics knowing artists seemed to be at least one semi-inchoate focus of outrage.

To some degree, you can understand the concerns. There’s a vision of journalistic objectivity which involves a reviewer ruthlessly evaluating the work in front of him or her without any reference to, or knowledge of the creator. The critic, in this view, is supposed to be a completely impartial observer, affixing a stamp of quality or animadversion so that readers can know that they are spending their hard-earned dollars in the best of all possible ways.

The reality is a lot messier. In part, that’s because, if you review a work positively, one of the things that often happens is that the creator of the work gets in touch with you to say, hey, awesome, you liked my work! Often creators will write me just to say thank you (which is lovely). Sometimes, though, they’ll contact me in the hopes that I might review their next book or project, too.

So, is that unethical? Now that I’ve talked to them, am I supposed to never write about their work again? That seems silly; the only reason I know them, after all, is that I like their work. I guess you could argue for some sort of disclosure — but what would I say? “Fair warning: I really like this creator’s work; this creator likes that I like their work. Now on to the review, where I say I like their work!”

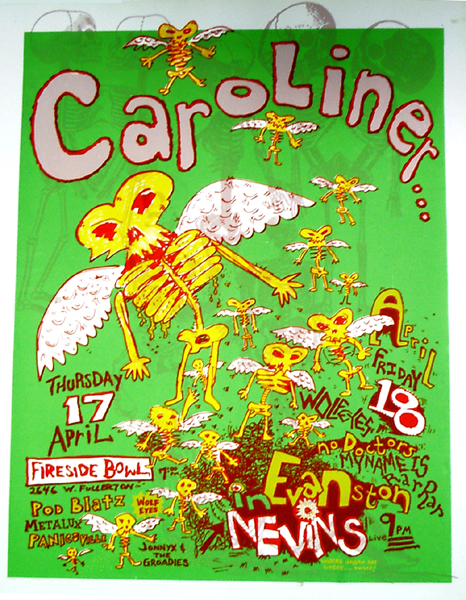

The thing is, when I do like somebody’s work, that can also open the way for other collaborations. Many writers and artists I admire, like Ariel Schrag, Edie Fake, and Stacey Donovan, have posted on my little, all volunteer blog at one point or another, because I love their work and when they appear in my inbox to say they liked a review, I’ll sometimes ask them if they would be interested in contributing. If you were determined to be offended by that sort of thing, you could argue it’s a quid pro quo, and that I’m receiving content (even if not money) for good reviews. Edie even designed the banner for my site (which I happily paid him for.) But again, the whole reason I find their contributions valuable is because I value their work — which is what I say whenever I write a review talking about how awesome Ariel Schrag and Edie Fake are.

The disconnect here isn’t just about ethics. It’s about the nature of criticism. A lot of the people posting to gamersgate seem to see reviews primarily as a way to make purchasing decisions. Reviews, from this perspective, are a buyer’s guide; it’s the equivalent of a consumer report. You don’t want the person who evaluates the gas mileage on your Prius to be buddies with the Prius manufacturers, because you’d worry that they might try to help their friend out by saying that the Prius gets better gas mileage than it does. You want an objective take on the value of that Prius.

But while objectivity makes sense as a goal in evaluating Priuses, it doesn’t as a goal for evaluating art. Criticism of art is always, by its nature subjective. And, at least for me, criticism tends to be less about saying, buy this or don’t buy this, and more about trying to engage with, and think about, what an artist is saying, or what a work is doing. A piece of criticism is as much about talking to, or with, the artist as it is providing a consumer report. On #gamersgate art is seen as a product, which is certainly one thing art can be. But art’s also a community. Which is why having actual conversations with the artist in question doesn’t seem like an ethical violation. Having conversations with the artist is my job.