At its core, Hollywood is an engine for turning pain, hardship, and trauma into shallow inspiration porn. From paralysis to the Holocaust, slavery to cancer; Hollywood cheerfully takes these blood soaked lemons and makes you drink blood soaked lemonade, albeit with lots of sweetener.

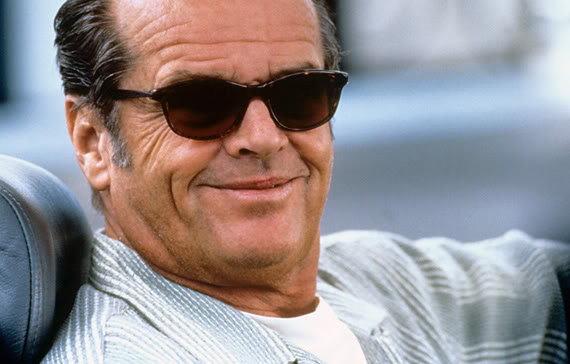

As Good As It Gets is firmly in the tradition, though the cocktail in question is perhaps more repulsive than most. Part of that is thanks to Jack Nicholson, whose smug self-regard can barely be contained in his constantly arching eyebrows. Most of the blame, though, rests squarely on the script.

For those lucky enough to have avoided the film since its release in 1997, I’ll briefly recap what I suppose I’ll have to refer to as the plot. Nicholson plays Melvin Udall, a fabulously wealthy romance novelist who suffers from some undefined form of OCD; he won’t step on cracks in the sidewalk, he locks the door five times every time he walks into his apartment; he opens a new bar of soap every time he washes his hands; he’s germphobic. Oh, and he’s also homophobic, racist, and deliberately abusive and cruel to everyone. But then he gets a dog, and a woman who looks like Helen Hunt and is 20 years younger than him decides inexplicably that he’s the guy for her. He gives her money to help her asthmatic son, life lessons and becomes a better person. The end.

There’s basically nothing to like in this film, but the bit that sticks out as particularly, drearily awful is the treatment of Melvin’s disability. At the Dissolve a while back, a commenter with OCD named Chapman Baxter argued that the film was correct in that people with OCD can engage in assholish behavior; “Although I’m not proud to admit it, I know from experience how a constant compulsion to do methodical rituals and the perpetual anxiety of intrusive thoughts can make one behave in quite an irritable and anti-social manner.” That seems reasonable…but I think it misses the main problem with what the film is doing.

The movie doesn’t just suggest that Melvin is a jerk because he has OCD. It suggests that the OCD and the jerkishness are essentially one and the same. When Melvin calls his gay neighbor a “fag”, it’s a sign of his quirky woundedness, just like his nervousness about stepping on cracks. And, similarly, when Melvin needs to eat at the same table in the same diner every day, that’s a character flaw on par with insulting a Jewish couple for having big noses. Melvin’s cruelty and his illness merge together, he’s at one and the same time responsible for both and for neither.

Because Melvin’s awfulness is an illness, he gets a pass; he can be spectacularly horrible, but still basically a good person underneath it all, since his behavior is essentially a medical condition, outside of his control. And because his illness is a character flaw, it is curable via the all-purpose nostrum of true love. Mixing flaws and sickness allows Hollywood to blend two of its favorite genres—the rom com and disability inspiration porn. The love of Carol, the waitress played by Hunt, makes Melvin want to become a better, less bigoted man—and that love simultaneously and spontaneously causes him to overcome his germphobia and other manifestations of his OCD. Mental illness and racism both evaporate with a kiss. Fall in love, and you can step on a crack.

This is supposed to be a happy ending for both Carol and Melvin, in theory. In fact, it’s impossible to imagine that this is a good long term choice for Carol, who, understandably, protests against her narrative fate, tearfully demanding to know why she has to settle for this decades older bigot who has just barely learned to form casual friendships, much less a serious romantic partnership. Carol’s mother is wheeled out on cue to tell her that nobody ever gets a perfect boyfriend—the uplifting message of the film being, you might as well settle, girl. We know you’re desperate.

Nor is this in any sense a happy ending for Melvin. Yes, Carol unaccountably decides to date him. But her love is precisely predicated on him becoming a better man–not just by being less of an asshole, but by being less mentally ill. There’s no sense that Carol is willing, able, or interested in dealing with Melvin’s illness; instead her love, the film assures us, will make that illness go away. What if it doesn’t, though? What happens to their relationship then?

As Good As It Gets, in short, is blandly contemptuous of both of its protagonists. Carol, with her asthmatic son, mentally ill boyfriend, and heart of gold, is a human mop, admirable by virtue of the selfless sopping up of her loved ones messes. When she suggests she might deserve more, her mother (presented as a moral voice of truth) tells her to quit kidding herself. Melvin, for his part, is presented as only worthy of love to the extent that love is a miraculous cure. Women are nurses who exist to make men normal. And if the woman doesn’t want to be a nurse, or the man isn’t instantly cured? Sorry, no rom com for you.

The forced happy ending is supposed to be inspiring; an unlikely boon to two wounded people. But instead it feels like an act of cynical, manipulative loathing. A working-class waitress with a sick kid; an aging man with OCD—without Hollywood pixie dust, no one gives a shit about you, the movie taunts. Follow the script for your gender and your illness, and all the normal people will maybe deign to sympathize. Romance! Cure! Come on kids; this is as good as it gets.